Healthcare in the US from a Global Perspective. Are we that good?

AB: This a good coverage on healthcare in the US as compared to other countries. It is long. It also has many charts and graphs rather than words. This is why I posted this at Angry Bear. It is easy to grasp the implications.

U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective, 2022, Commonwealth Fund, Munira Z. Gunja, Evan D. Gumas, Reginald D. Williams II

Introduction

In the previous edition of U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective, we reported that people in the United States experience the worst health outcomes overall of any high-income nation.1 Americans are more likely to die younger, and from avoidable causes, than residents of peer countries.

Between January 2020 and December 2021, life expectancy dropped in the U.S. and other countries.2 With the pandemic a continuing threat to global health and well-being, we have updated our 2019 cross-national comparison of health care systems to assess U.S. health spending, outcomes, status, and service use relative to Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, South Korea, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. We also compare U.S. health system performance to the OECD average for the 38 high-income countries for which data are available. The data for our analysis come from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and other international sources (see “How We Conducted This Study” for details).

For every metric we examine, we used the latest data available. This means

that results for certain countries may reflect the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when mental health conditions were surging, essential health services were disrupted, and patients may not have received the same level of care.3

Highlights

- Health care spending, both per person and as a share of GDP, continues to be far higher in the United States than in other high-income countries. The U.S. is the only country not having universal healthcare..

- The U.S. has the lowest life expectancy at birth, the highest death rates for avoidable or treatable conditions, the highest maternal and infant mortality, and among the highest suicide rates.

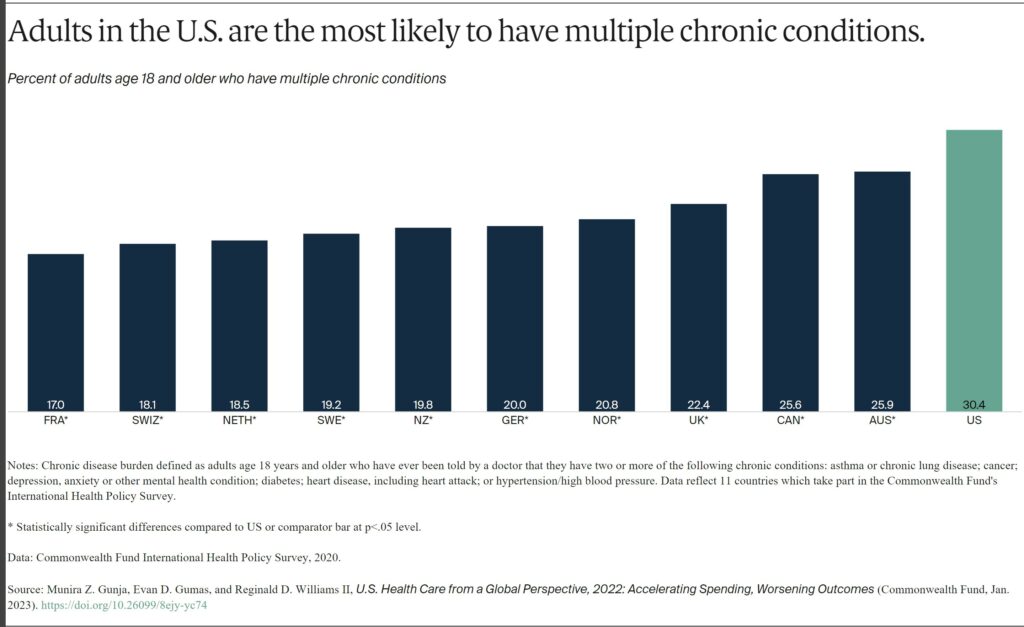

- The U.S. has the highest rate of people with multiple chronic conditions and an obesity rate nearly twice the OECD average.

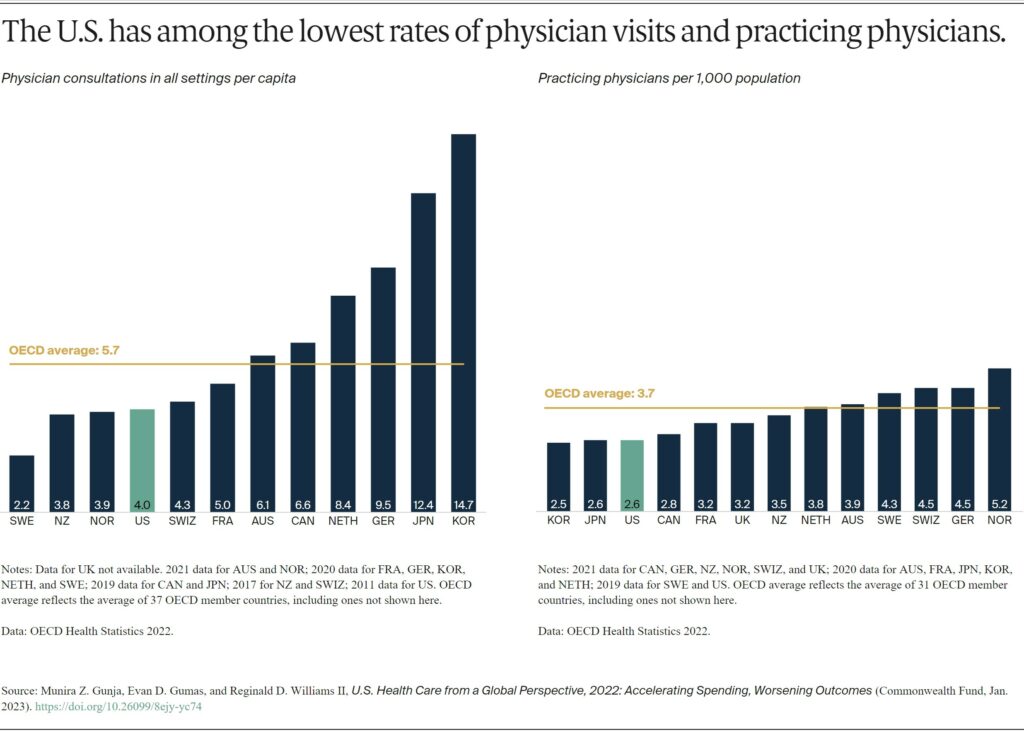

- Americans see physicians less often than people in most other countries and have among the lowest rate of practicing physicians and hospital beds per 1,000 population.

- Screening rates for breast and colorectal cancer and vaccination for flu in the U.S. are among the highest, but COVID-19 vaccination trails many nations.

Findings

Health Care Spending and Coverage

In all countries, health spending as a share of the overall economy has been steadily increasing since the 1980s, as spending growth has outpaced economic growth.4 This growth is in part because of medical technologies, rising prices in the health sector, and higher demand for services.5 In 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic began, health care spending rose rapidly in nearly all countries. Governments sought to mitigate the spread of the disease through COVID testing, vaccine development, relief funds, and other measures.6 Since then, spending has slowed but still remains higher from years prior.7

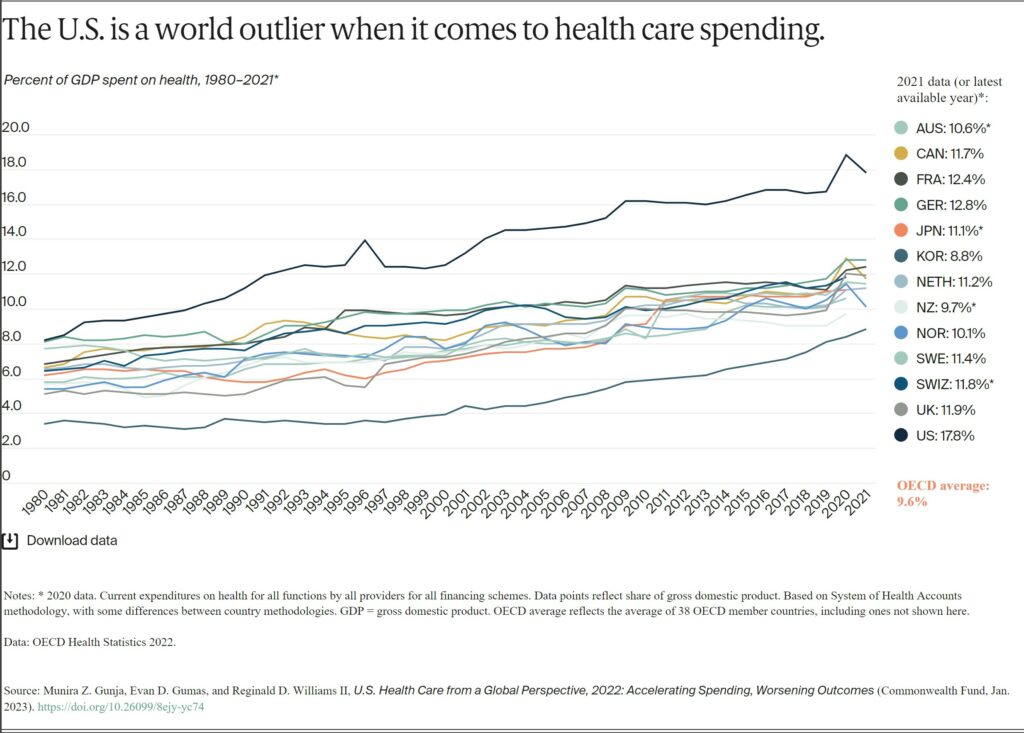

In 2021, the U.S. spent 17.8 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) on health care, nearly twice as much as the average OECD country.

AB: In spite of predictions and forecasts, spending has hovered around 17% with the exceptio of during the pandemic.

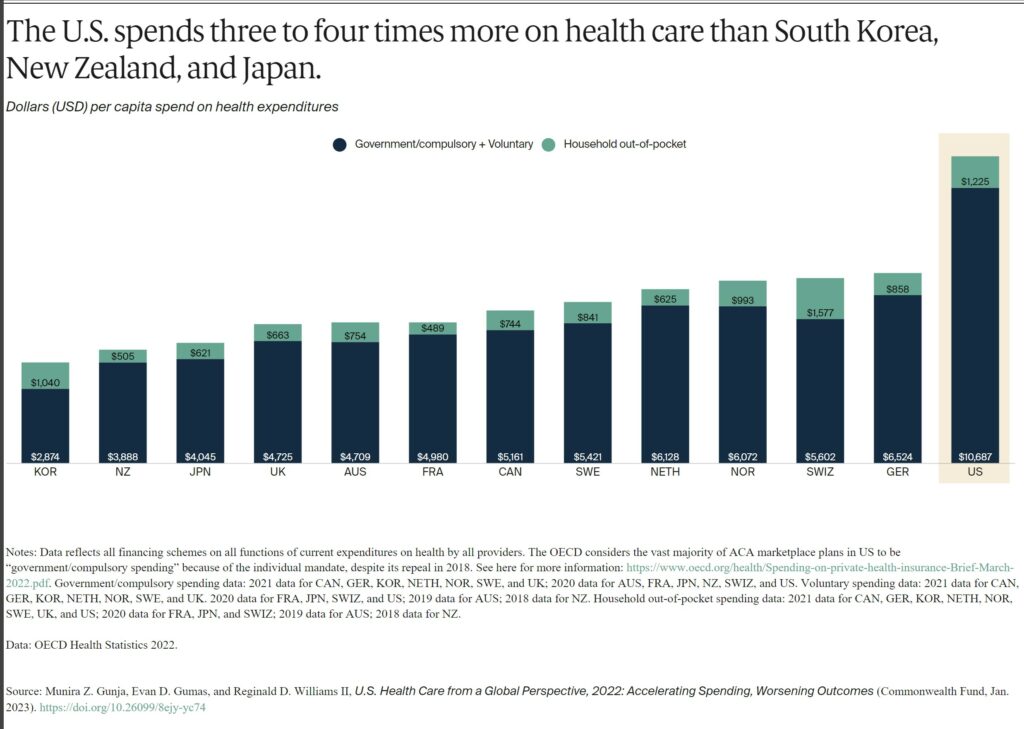

Health spending per person in the U.S. was nearly two times higher than in the closest country, Germany. It was also four times higher than in South Korea. This includes spending for people in public programs such as Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Program, Medicare, and military plans. It includes spending by those with private employer-sponsored coverage or other private insurance plus out-of-pocket health spending.

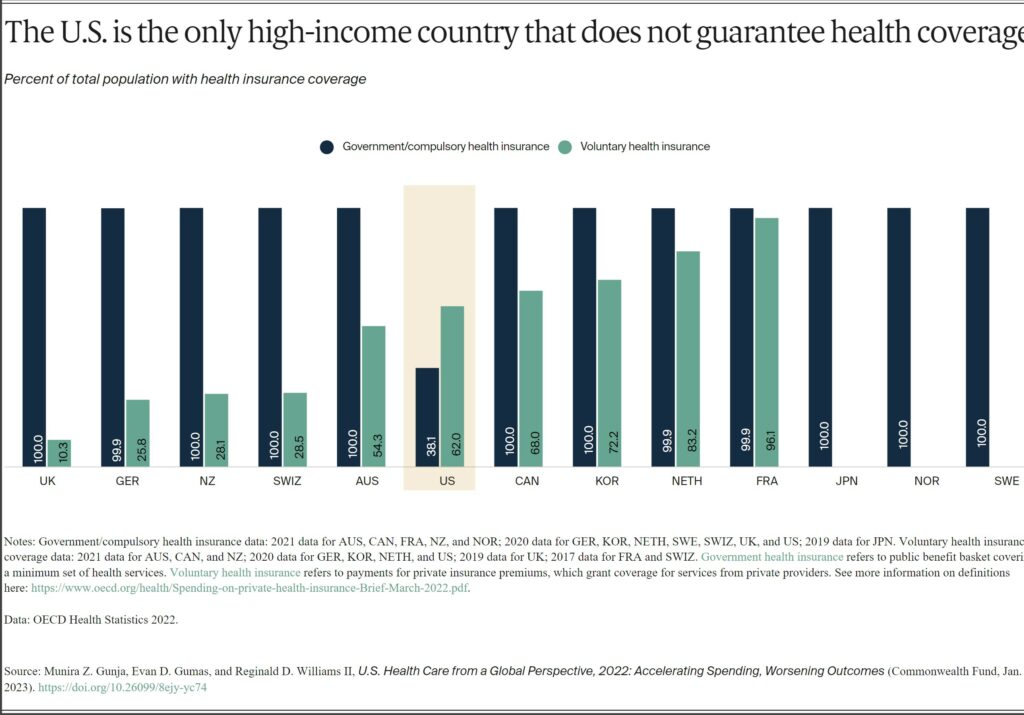

Except for the US, all the countries in this analysis guarantee government, or public, health coverage to all their residents. In addition to public coverage, people in several of the countries have the option to also purchase private coverage. In France, nearly the entire population has both private and public insurance.

In 2021, 8.6 percent of the U.S. population was uninsured.8 The U.S. is the only high-income country where a substantial portion of the population lacks any form of health insurance.

Health Outcomes

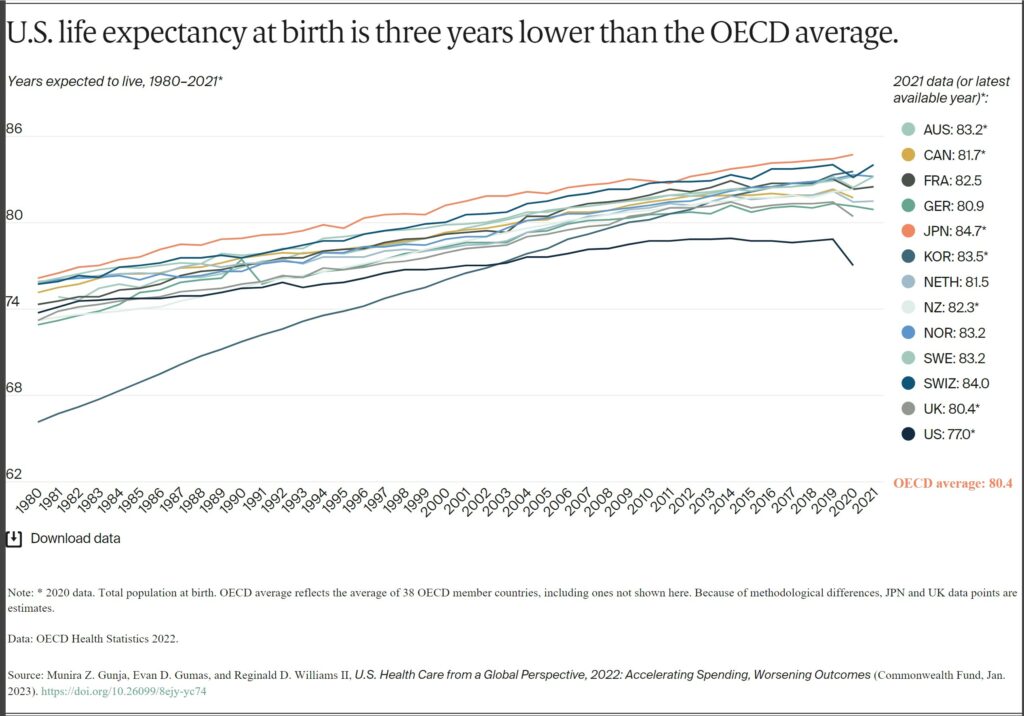

Despite high U.S. spending, Americans experience worse health outcomes than their peers around world. For example, life expectancy at birth in the U.S. was 77 years in 2020. This is three years lower than the OECD average. Provisional data shows life expectancy in the U.S. dropped even further in 2021.9

Life expectancy in the US masks racial and ethnic disparities.10 Average life expectancy in 2019 for non-Hispanic Black Americans (74.8 years) and non-Hispanic American Indians or Alaska Natives (71.8 years) is four and seven years lower, respectively, than it is for non-Hispanic whites (78.8 years).

Meanwhile, life expectancy for Hispanic Americans (81.9 years) is higher than it is for whites and similar to life expectancy in the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Canada. As a group, Asian Americans have a higher life expectancy (85.6 years) than people in Japan.

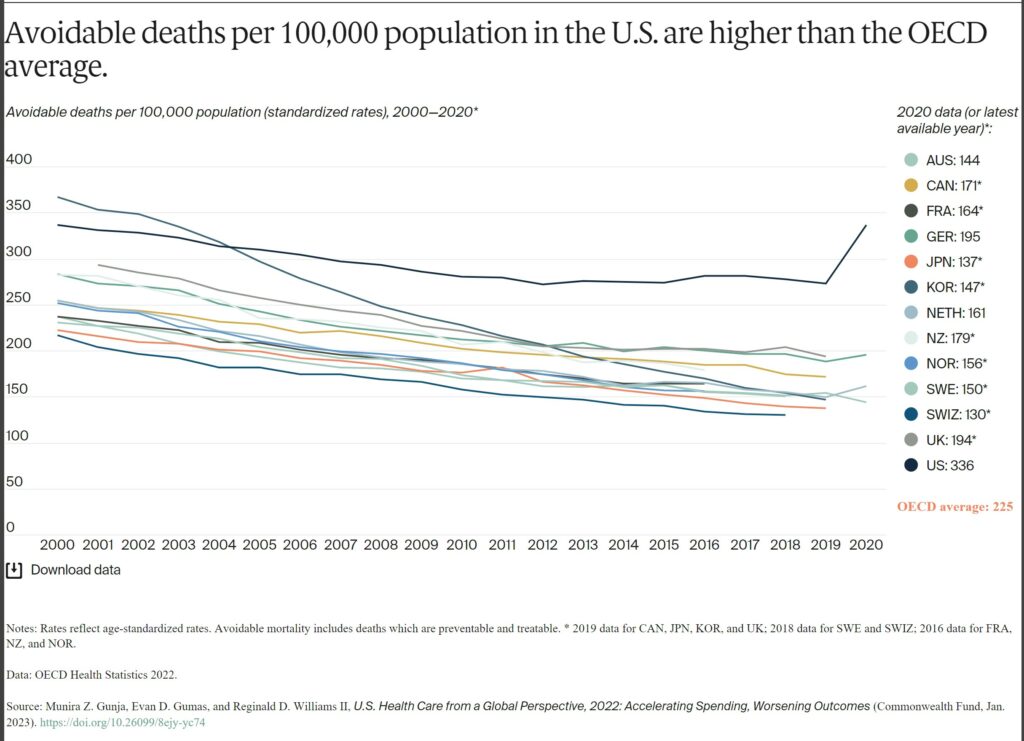

Avoidable mortality refers to preventable deaths and treatable illness. Preventable deaths can be avoided through effective public health measures and through primary prevention, such as nutritional diet and exercise. Treatable mortality can be avoided mainly through timely and effective health care interventions, including regular exams, screenings, and treatment.11 Since 2015, avoidable deaths have been on the rise in the U.S., which had the highest rate in 2020 of all the countries in our analysis.

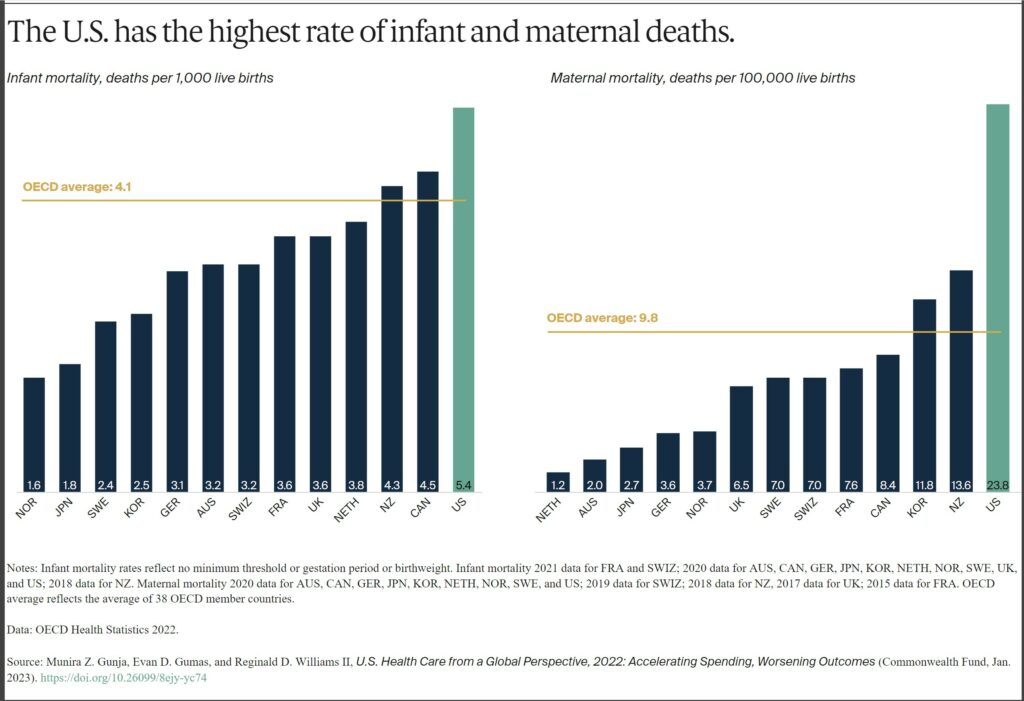

In 2020, the infant mortality rate in the U.S. was 5.4 deaths per 1,000 live births, the highest rate of all the countries in our analysis. In contrast, there were 1.6 deaths per 1,000 live births in Norway.

Women in the U.S. have experienced the highest rate of maternal mortality related to complications of pregnancy and childbirth. In 2020, there were nearly 24 maternal deaths for every 100,000 live births in the U.S., more than three times the rate in most other high-income countries we studied. A high rate of cesarean section, inadequate prenatal care, and socioeconomic inequalities contributing to chronic illnesses like obesity, diabetes, and heart disease may all help explain high U.S. infant and maternal mortality.12

AB: I will add to this. Biden’s maternal healthcare policy was extended to one year for Medicaid (unless some one tells me differently). As I wrote in “A Woman’s Right to Safe Healthcare Outcomes, Angry Bear” giving birth to a child is more dangerous in the US. I was fortunate to watch the birth of my three. This occurs even if you have a good healthcare policy.

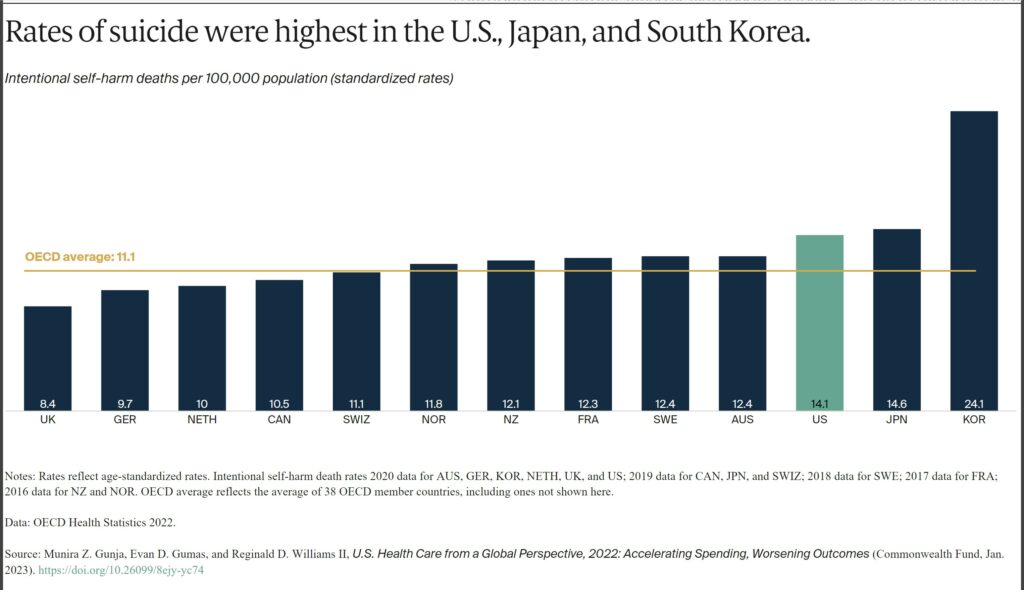

Having dramatically increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, suicide rates can indicate a high burden of mental illness.13 The U.S. has the third-highest suicide rate, while the U.K. has the lowest — nearly half the U.S. rate.

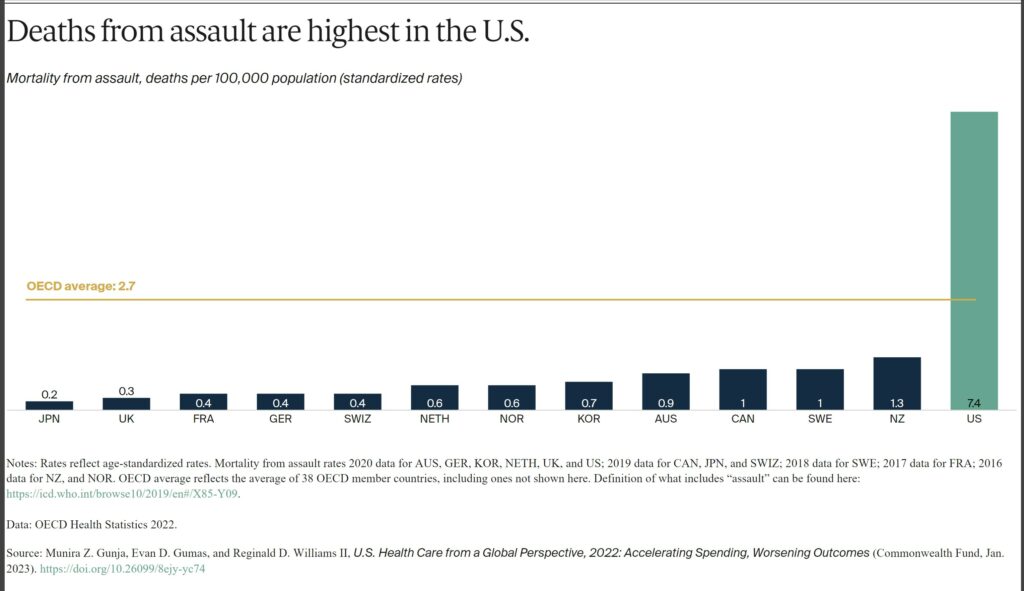

The U.S. is an outlier in deaths from physical assault, which includes gun violence. Its 7.4 deaths per 100,000 people is far above the OECD average of 2.7, and at least seven times higher than all other high-income countries in our study, except New Zealand.

Health Status

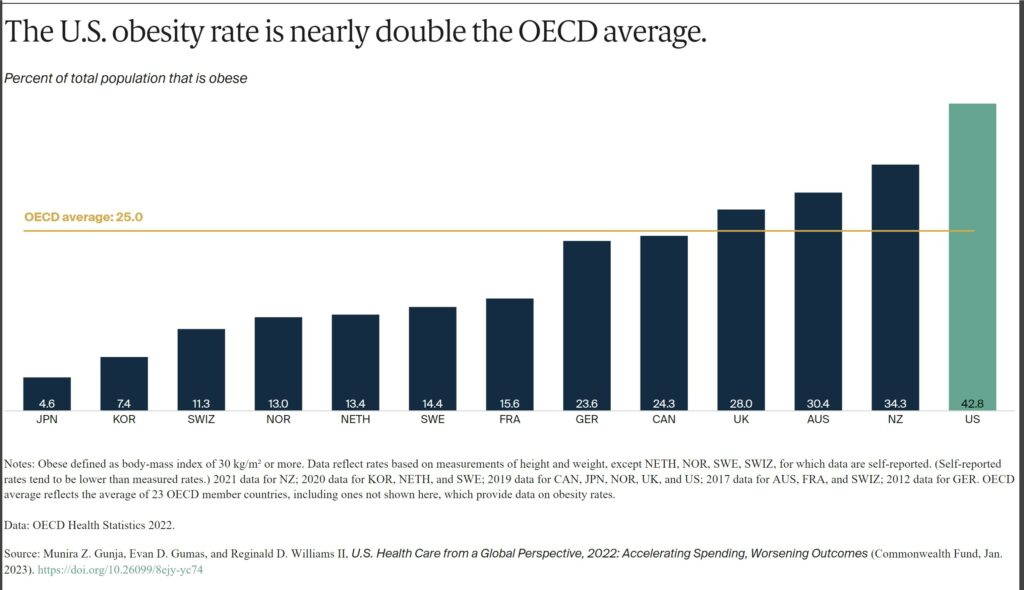

Obesity is a key risk factor for chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases, and cancer. Issues contributing to obesity include unhealthy living environments, poor diet, food and agricultural sectors, lower socioeconomic status, and higher rates of behavioral health problems.14

The U.S. has the highest obesity rate among the countries we studied, where data was available — nearly two times higher than the OECD average.

In 2020, three of 10 U.S. adults surveyed said at some point in their lifetime they had been diagnosed with two or more chronic conditions such as asthma, cancer, depression, diabetes, heart disease, or hypertension. No more than a quarter of residents in the other countries studied reported the same, and the U.S. rate was nearly twice as high as France’s.

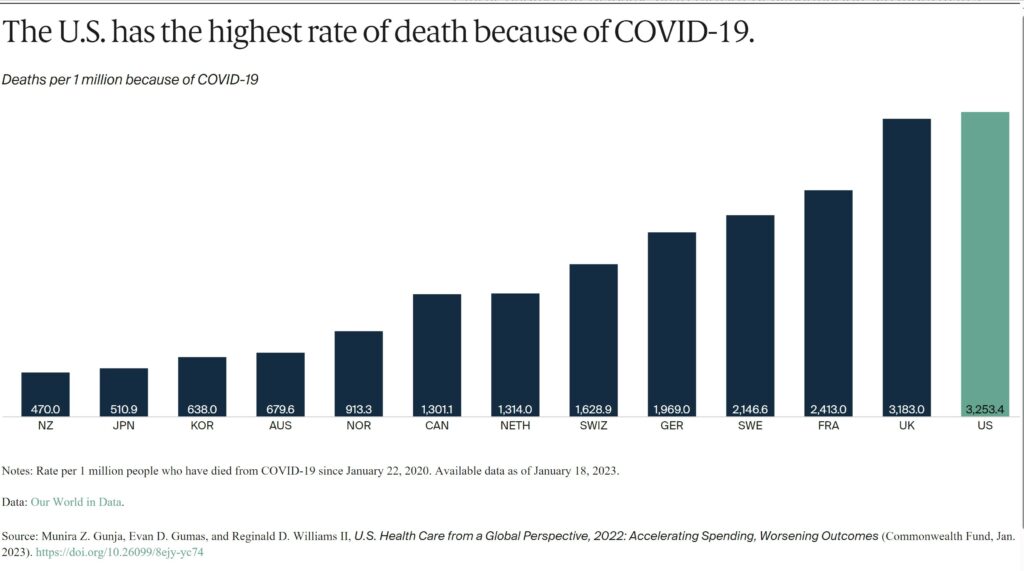

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, more people in the U.S. have died from the coronavirus than in other high-income countries. For every 1 million cases between January 22, 2020, and January 18, 2023, there were more than 3,000 deaths in the U.S.

Health Care Use

While U.S. health care spending is the highest in the world, Americans overall visit physicians less frequently than residents of most other high-income countries. At four visits per person per year, Americans see the doctor less often than the OECD average.

Less-frequent physician visits may be related to the comparatively low supply of physicians in the U.S., which is below the average number of practicing physicians in OECD countries.

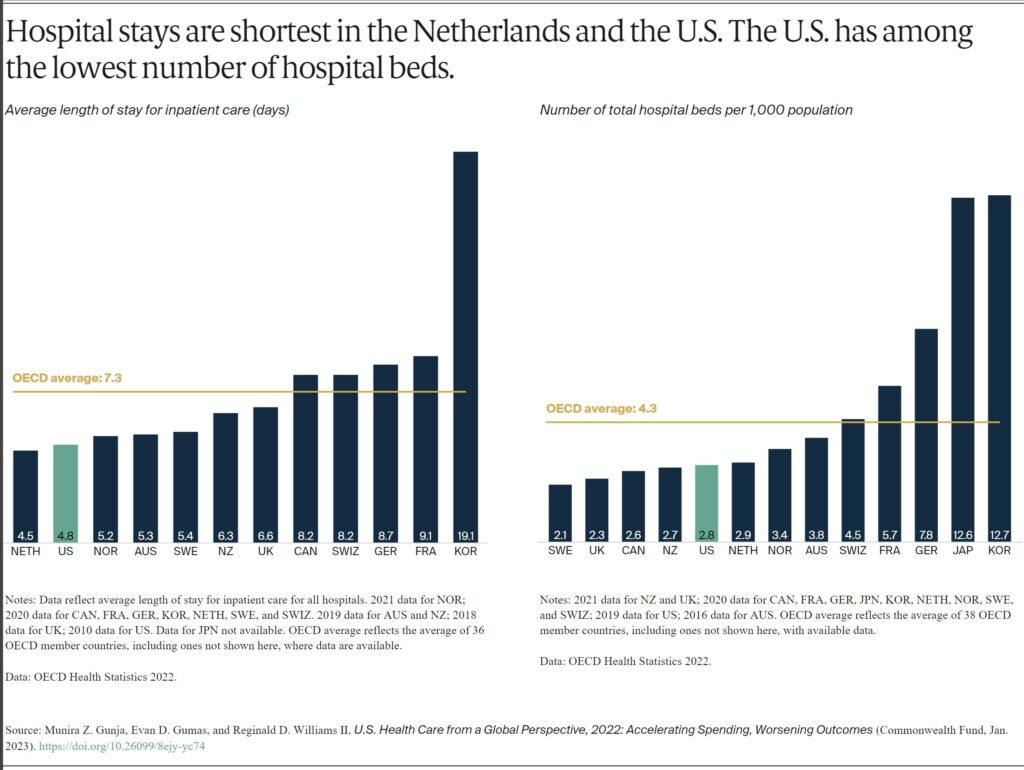

The average length of a hospital stay in the U.S. for all inpatient care was 4.8 days. This is far lower than the OECD average. The U.S. had 2.8 hospital beds per 1,000 population, lower than the OECD average of 4.3.

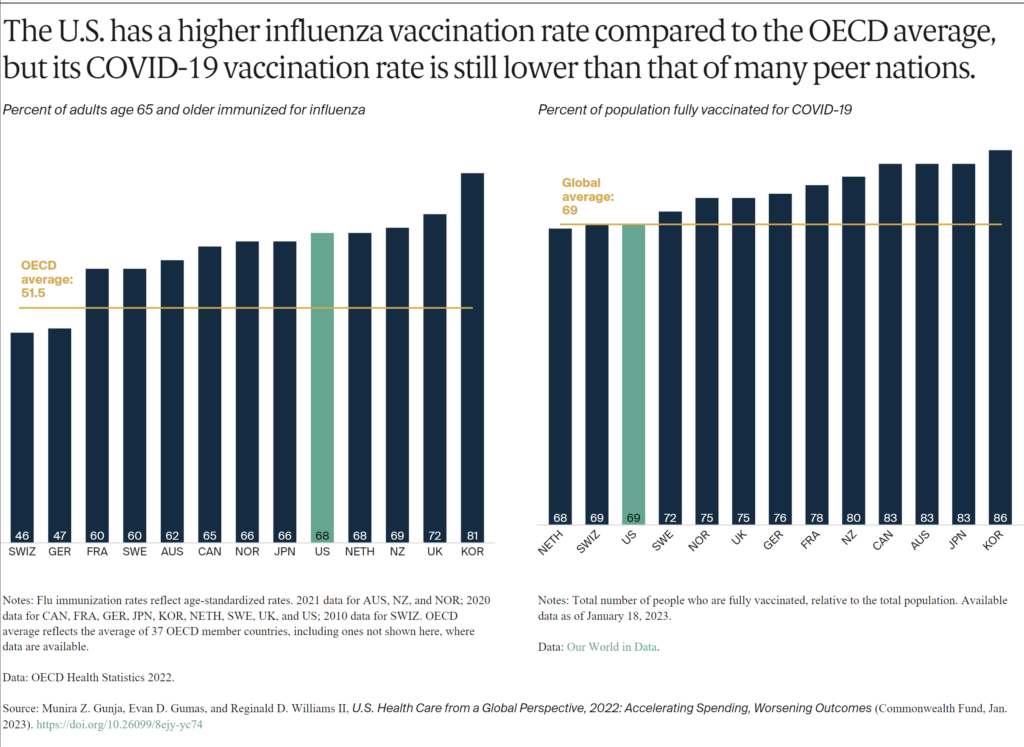

More than two-thirds of older Americans receive the flu vaccine. This is similar to older residents of several other high-income countries, and more than the OECD average.

The U.S., however, has one of the lowest COVID-19 vaccination rates among high-income countries. As of January 2023, 69 percent of the population were fully vaccinated, compared to 86 percent in South Korea, although rates are regularly being updated.

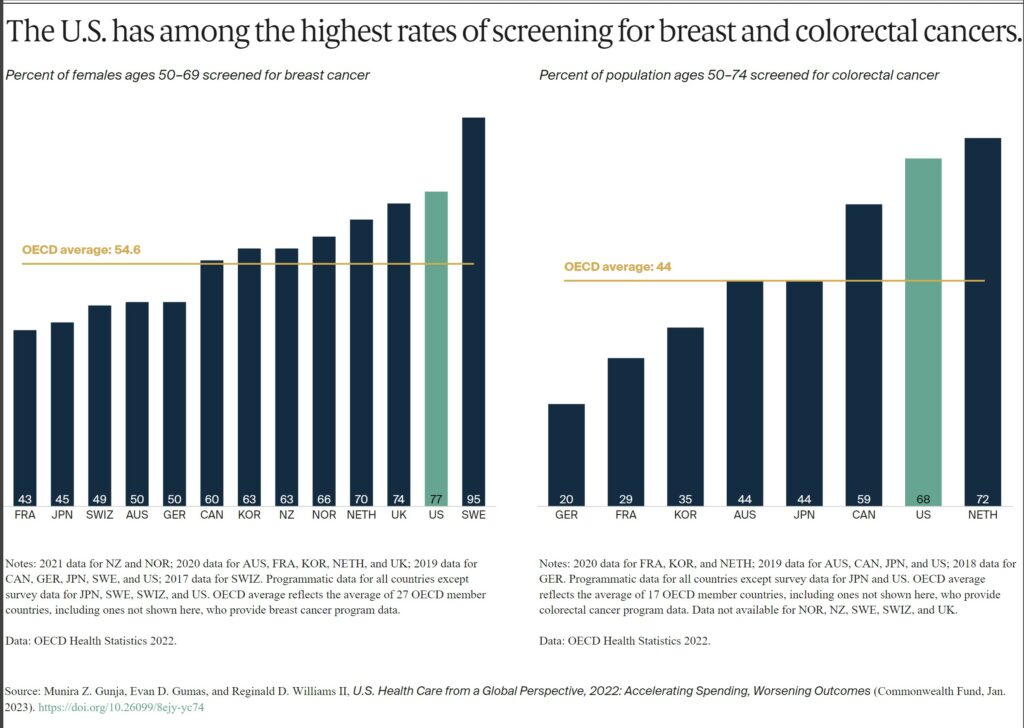

The U.S. does relatively well with cancer prevention. This is likely a reflection of extensive screening and detection. Such measures are a key to diagnosing breast and colorectal cancers early and beginning treatment in a timely manner.15

The U.S. and Sweden had the highest number of breast cancer screenings among women ages 50 to 69 and notably higher than the OECD average. In contrast, just 43 percent of women ages 50 to 69 were screened in France. When it comes to colorectal cancer screening, the U.S. exceeded the OECD average and had among the highest rates.

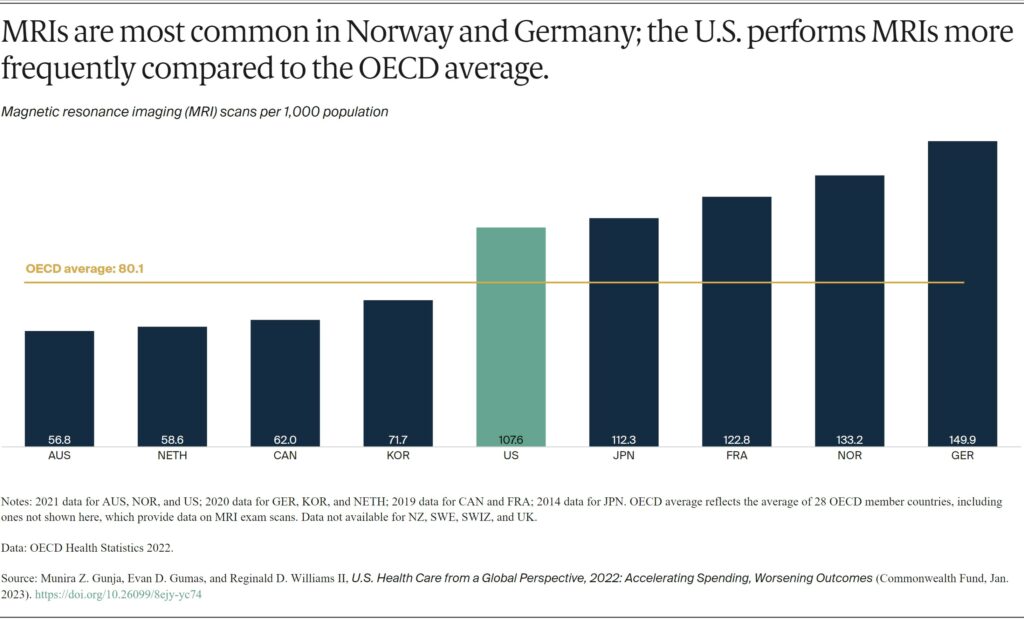

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a common and effective imaging technique for diagnosing and tracking the treatment of a variety of illnesses. The countries using these specialized scans the most are the U.S., Japan, France, Norway, and Germany, with more than 100 scans per 1,000 people.

The U.S. has a high number of MRI units available to physicians, about 38 units for every 1 million people in 2018. That’s the second-highest rate in the world behind Japan, which has 51.7 units per 1 million people.16

The clinical benefit as a diagnostic tool are well documented. MRIs are also particularly expensive in the U.S., averaging $1,119.17 The cost is 42 percent more than the U.K.’s average cost and 420 percent more than Australia’s. And while MRIs are accessible in the U.S., Americans spend far more on them than their international peers do.18

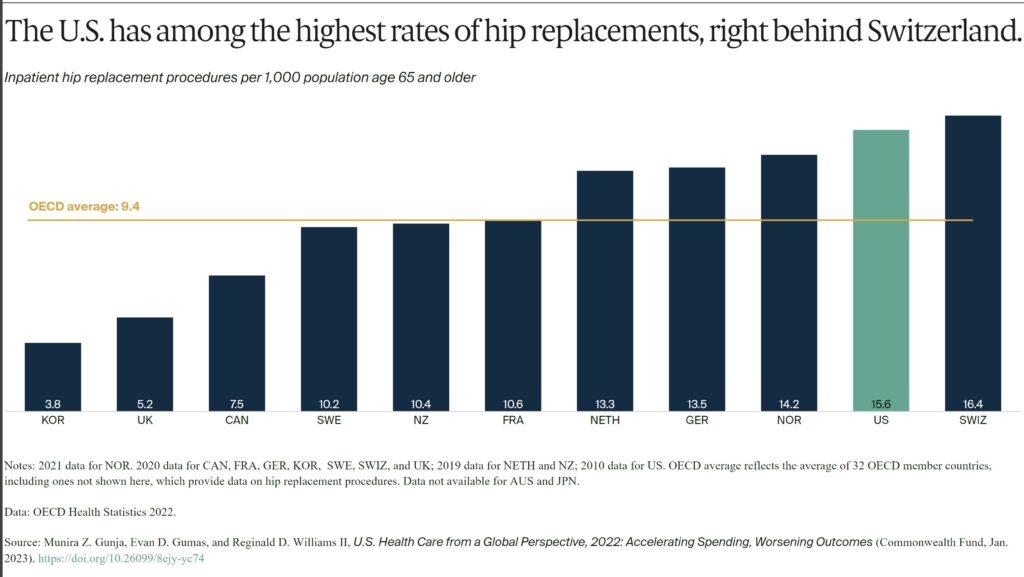

Globally, the rates of hip replacement are increasing as populations age and develop conditions such as osteoarthritis. It is the leading reason for the procedure, which can substantially improve an individual’s quality of life.19 Hip replacements are an important indicator of the prevalence of osteoarthritis in a population.

Discussion On US Healthcare

The United States spends more on health care than any other high-income country. The nation often performs worse on measures of health and health care. For the U.S., a first step to improvement is ensuring that everyone has access to affordable care. Not only is the U.S. the only country we studied not having universal health coverage, its health system appears to be designed to discourage people from using services.

Affordability remains the top reason why some Americans do not sign up for health coverage. High out-of-pocket costs cause nearly half of working-age adults to skip or delay getting needed care.20 The Inflation Reduction Act will help reduce the high cost of certain drugs and cap out-of-pocket costs for older Americans. It is a step in the right direction.21 But it will take much more to make health care as easy to access as it is in other high-income countries.

A second step is containing costs. Other countries have achieved better health outcomes while spending much less on health care overall. In the U.S., high prices for health services continue to be the primary driver of this elevated spending.22 Policymakers and health systems could look to some of the approaches taken by other nations to contain overall health spending, including the care and the administrative costs.

A third step is better prevention and management of chronic conditions. Critical to this is developing the capacity to offer comprehensive, continuous, well-coordinated care. Decades of underinvestment, along with an inadequate supply of health care providers, have limited American access to effective primary care.23

The findings of our international comparison demonstrate the importance of a health care system supporting chronic disease prevention and management. Much less, the early diagnosis and treatment of medical problems, affordable access to health care coverage, and cost containment. All are among the key functions of a high-performing system. Since other countries have found ways to do these things well, the U.S. could also.

Tremendous post.

I assume that the figures displayed are averages and I wonder how much of the results are due to disparities of healthcare between affluent and poor.

@ Jack,

“Poverty and Health

“SDoH are the conditions under which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, and include factors such as socioeconomic status, education, employment, social support networks, and neighborhood characteristics.4 These social factors have a more significant collective impact on health and health outcomes than health behavior, health care, and the physical environment.17,18 SDoH, especially poverty, structural racism, and discrimination, are the primary drivers of health inequities.19,20

“Economic prosperity can provide individuals access to resources to avoid or buffer exposure to health risks.21 Research shows that individuals with higher incomes consistently experience better health outcomes than individuals with low incomes and those living in poverty.22 Poverty affects health by limiting access to proper nutrition and healthy foods; shelter; safe neighborhoods to learn, live, and work; clean air and water; utilities; and other elements that define an individual’s standard of living. Individuals who live in low-income or high-poverty neighborhoods are likely to experience poor health due to a combination of these factors.23,24

“Violence is also more prevalent in areas with greater poverty. From 2008 to 2012, individuals in households at or below the poverty level experienced more than double the rate of violent victimization than individuals in high-income households.25 This pattern of victimization by violent behavior was consistent for both Black and white individuals. It significantly impacts the victim’s family and perpetrator’s family (through incarceration).”

https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/poverty-health.html#:~:text=Economic%20prosperity%20can%20provide%20individuals,buffer%20exposure%20to%20health%20risks.&text=Research%20shows%20that%20individuals%20with,and%20those%20living%20in%20poverty.

Joel,

If I’m understanding this correctly, the disparity in health outcomes is as much, if not more, the result of wealth disparity as it is the healthcare system.

@Jack,

In a healthcare system that depends on money, it’s a distinction without a difference.

That’s why we need single payer, like all the other industrialized nations on the planet.

Well, but that suggests that the healthcare system is adequate to serve everyone if there were a single payor. I wonder if that’s true. Consider how consolidation of healthcare providers has tended to result in the closing of rural hospitals.

@Jack,

Generally when people use the term “single payer,” they’re not referring to a business monopoly. The healthcare systems of all the other industrialized nations on the planet are adequate to serve all their citizens. Why couldn’t America adopt one of those models?

Perhaps they could but to get adequate capacity, the system would have to build, maintain, and staff facilities and possibly finance medical education as well In other words, you’d have government operated medical care as opposed to government financed medical care. I doubt that private enterprise would invest in many areas needing facilities if they were limited to government authorized rates. As you know, in our present system there are providers who will not accept medicaid patients and some won’t accept medicare patients either though that’s not as common.

Jack:

The present system has costs 15-20% administrative due to commercial healthcare insurance. What you are now considering are commercial healthcare entities which have grown large enough to absorb other hospitals and in fact close them and large enough to force cuts in costs of insurance not to benefit the insured patients but to line their pockets. Single payer/payor would set the pricing.

The closest bill to single payer was Representative Jayapal’s bill, HR 1384. It met the definition of a single-payer bill as originally outlined in PNHP’s 1989 article and as most experts define the term. It contains the four elements of a single-payer system:

– It relies on one payer (HHS, not multiple payers called ACOs) to pay hospitals and doctors directly,

– it authorizes budgets for hospitals,

– it establishes fee schedules for doctors, and

– it has price ceilings on prescription drugs.

Rep Jayapal and Sen Sanders Have Introduced Medicare For All Bills: Part 2

Exactly, and that’s my point. The government would have to finance and/or build much of that if it’s going to set the prices, especially out in the country. Then, too, as someone pointed out earlier, a concierge approach would likely be favored by much of the private medical investment.

Jack:

At 17% of GDP, I do not think they need much more financing than they already have today. The percentage may stay the same, the market keeps growing.

Bill, at the current level of financing, rural hospitals and clinics are being closed.

Jack:

Different scenario. The ones making the big bucks are the hospital conglomerates.

Small Town and Rural Hospitals Are at Risk of Closing due to Funding

Part 2: A Better Way (Potentially) to Fund Rural Hospitals

The hospital conglomerates wouldn’t be induced to provide care in rural and poverty stricken areas by single payor; they would just concentrate on where the most money can be made.

Jack:

The compensation will be the same or minimal in difference. NEJM: Demystifying Urban Versus Rural Physician Compensation

“Even though that might be the case for some opportunities in rural areas — defined variably in the market as either a population of 20,000 or fewer or up to 50,000 and fewer — it’s not that straightforward. And where a differential does exist that positions a rural practice opportunity as more financially lucrative than a comparable urban one, the compensation difference might not be a significant as some young physicians think. Recruiting professionals and consultants who help organizations structure physicians’ compensation packages concur that while physicians who consider rural opportunities will surely be wooed, welcomed, and financially accommodated to the extent that hiring organizations are able, they shouldn’t expect a bonanza.

In other words, urban myths — that physicians who take a rural opportunity in the Plains region will start out earning 25 to 30 percent more annually than their colleagues in Chicago are just that: myths. The reality, according to Patrice Streicher, senior operations manager in Vista Staffing’s permanent search division, is that the difference will be more in the neighborhood of 5 to 10 percent. “I can say on the record that, based on what we’re seeing, the difference will be minimal — maybe 10 percent at the most — between compensation in a rural versus urban or mid-sized community.” And the salary component of the offer is pretty much the same, regardless of the location, said Ms. Streicher, a National Association of Physician Recruiters board member.

“Five years ago, the rural offers might have had much higher salaries and different structures than urban ones, but with the growth of telemedicine and other market developments, that’s no longer the case,” she said.”

I have been working with Kip Sullivan on Single Payer. This akin to maufacturing and product costs.

Well, that’s for physicians generally but doesn’t address hospital accessibility or specialized testing facilities nor, indeed, physician specialists. Then there’s the desirability of the communities themselves for the individual doctors. They do tend to favor urban assignments regardless of slight differences in compensation.

Jack:

You know, my open heart-surgery was done is a smaller town of Mansfield which was also the site for the Shawshank Redemption movie. It is nestled neatly between Cleveland and Columbus. Mansfield Hospital is 1/3 the size of either hospital and was probably even a smaller ratio then. For some reason, they had a Cleveland Clinic doctor there who is still there as of now.

Lexington/Mansfield has a total population of ~150,000. Mansfield has a high crime rate.

Both of the articles I submitted in the line of comments address most if not every point you are making. Yes, there are issues with major systems gobbling up small hospitals and then closing them. The programs are there to support smaller hospitals, the enforcement to make sure they go to smaller hospitals has been lacking. That is a true issue.

I have presented two articles earlier which cover your complaints. The second article provides a via solution. That you may not agree with it or fins as somewhat inadequate does not make your point true. I find the solution(s) viable and realistic. We have a solution and your complaint should be about the powers to be not doing much about it.

The third article from the NEJM discusses salary and benefits and why people go to smaller hospitals. The Ohio Medical is a good example of this as a Cleveland Clinic heart specialist went there and is still there. The proximity to both Cleveland and Columbus is doable. Of course you could run me around with another issue which I could probably answer. This is reminiscent of the Fray. What about this and what about that?

I do not claim to be a healthcare expert other than being in a hospital multiple times for surgeries and treatment for an incurable blood disorder which probably can be traced back to LeJeune. My experience is working with Maggie Mahar and Kip Sullivan has allowed me to learn or take in a large amount of info. Gary Early and I have talked about Lejeune and Suzanne Gordon (his wife) has written about the VA and its issues.

I believe I have answered the questions adequately and provided a foundation for solution. Like everything else, the solutions may be adequate but there is always a political side to whatever is done. I have no solution for politics.

Last comment.

I respect your “last comment” and only offer a clarification. I was leading up to urging antitrust actions in the medical economy and intending to argue that action was necessary to make single payor effective. I am not opposed to some form of single payor, probably universal medicare, but rather the notion that by itself single payor will solve the availability of healthcare for all.

There is no change to US wealth or income inequality that gets every American access to concierge medicine and unlimited care at any price. The payment structure is utterly broken, but this survey also indicates that the service infrastructure and standards of care underneath are rotten as well.

https://academic.oup.com/pnasnexus/article/2/6/pgad173/7185600

May 29, 2023

Missing Americans: Early death in the United States—1933-2021

By Jacob Bor, Andrew C Stokes, Julia Raifman, Atheendar Venkataramani, Mary T Bassett, David Himmelstein and Steffie Woolhandler

Significance Statement

One million US deaths in 2020 and 1.1 million US deaths in 2021 would have been averted if the United States had the mortality rates of other wealthy nations. About half of these missing Americans died before age 65. The number of excess US deaths relative to peers is unprecedented in modern times, at least since the 1930s. These excess US deaths were a result of a decades-long divergence in mortality from other wealthy nations, beginning in the 1980s, and were further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The use of an international benchmark highlights unfavorable mortality trends involving all US racial/ethnic groups and disproportionately affecting younger and working-age adults.

https://academic.oup.com/pnasnexus/article/2/6/pgad173/7185600

May 29, 2023

Missing Americans: Early death in the United States—1933-2021

By Jacob Bor, Andrew C Stokes, Julia Raifman, Atheendar Venkataramani, Mary T Bassett, David Himmelstein and Steffie Woolhandler

Abstract

We assessed how many US deaths would have been averted each year, 1933–2021, if US age-specific mortality rates had equaled the average of 21 other wealthy nations. We refer to these excess US deaths as “missing Americans.” The United States had lower mortality rates than peer countries in the 1930s–1950s and similar mortality in the 1960s and 1970s. Beginning in the 1980s, however, the United States began experiencing a steady increase in the number of missing Americans, reaching 622,534 in 2019 alone. Excess US deaths surged during the COVID-19 pandemic, reaching 1,009,467 in 2020 and 1,090,103 in 2021. Excess US mortality was particularly pronounced for persons under 65 years. In 2020 and 2021, half of all US deaths under 65 years and 90% of the increase in under-65 mortality from 2019 to 2021 would have been avoided if the United States had the mortality rates of its peers. In 2021, there were 26.4 million years of life lost due to excess US mortality relative to peer nations, and 49% of all missing Americans died before age 65. Black and Native Americans made up a disproportionate share of excess US deaths, although the majority of missing Americans were White.

What are the mechanisms to fund single payer? Not saying it is too expensive, just that transferring from a lot of private insurance to public presumes that most or all of these private funds – including copays and deductibles – somehow migrate to the new system. What are the proposed mechanisms? I keep in mind that the 50 employee employer mandate of ACA lasted even shorter than the individual mandate if I recall correctly.

@Eric,

“What are the mechanisms to fund single payer?”

There are several models of single payer working out there, each funded differently. But if every other industrialized nation on the planet can insure all its citizens get healthcare without being bankrupted, surely at least one of those mechanisms could work in the USA.

and if the other countries with smaller economies can do it, why cant we? are we that much less able to do?