A machine learning algorithm can identify 500 people, who go on to be shot within 18 months.

– by Sara B. Heller and Max Kapustin

Econofact, November 2022

Let me be clear on the topic before you read the article. The full text is: “In a research paper with colleagues, we find that it is possible, using data such as arrest and victimization records that cities already collect, to accurately identify specific people at high risk of being shot without introducing the kinds of racial bias that are of most concern in algorithmic prediction. For example, a machine learning algorithm trained on such data in Chicago can identify 500 people, almost 13 percent of whom go on to be shot within 18 months.

I find the message stunning.

The Issue:

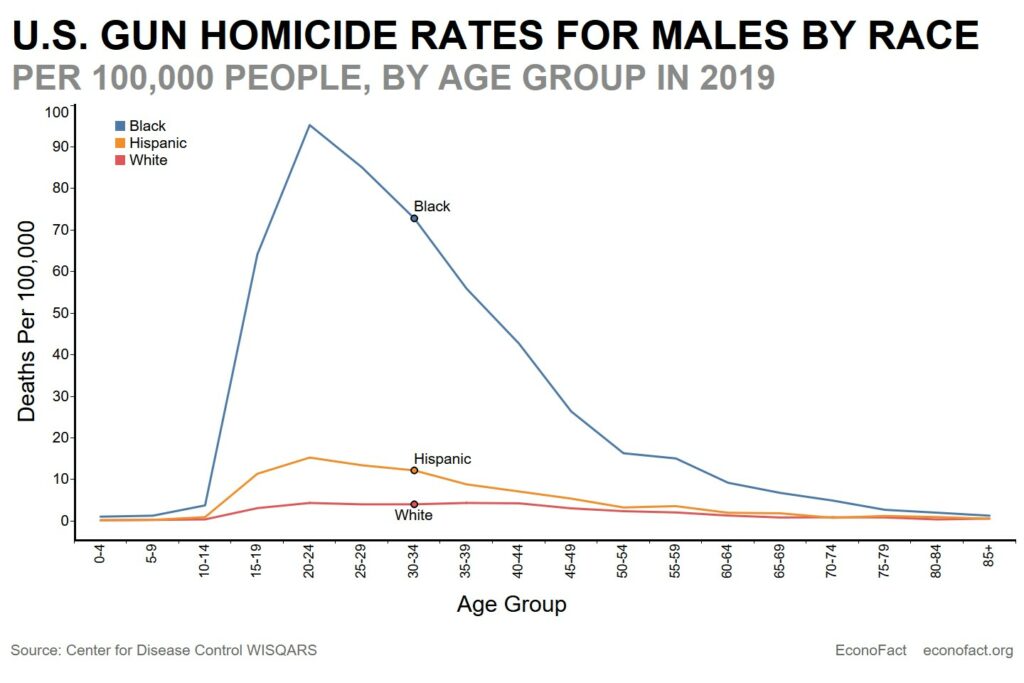

In 2020, almost 25,000 people were murdered in the U.S. Nearly 80% of them were with a firearm. That year saw homicides rise by 30%, the largest single year increase on record, with almost all the new deaths due to firearms. This level of gun violence generates enormous and unevenly distributed social costs. The burden is particularly severe for young people and young men of color. Guns are now the leading cause of death among children and adolescents in the U.S. (including suicides and accidents). Gun homicide is the leading cause of death for young Black men. Exposure to gun violence generates far-reaching harm to children and families well beyond the victims directly involved, with a disproportionate impact on economically marginalized communities.

The Facts:

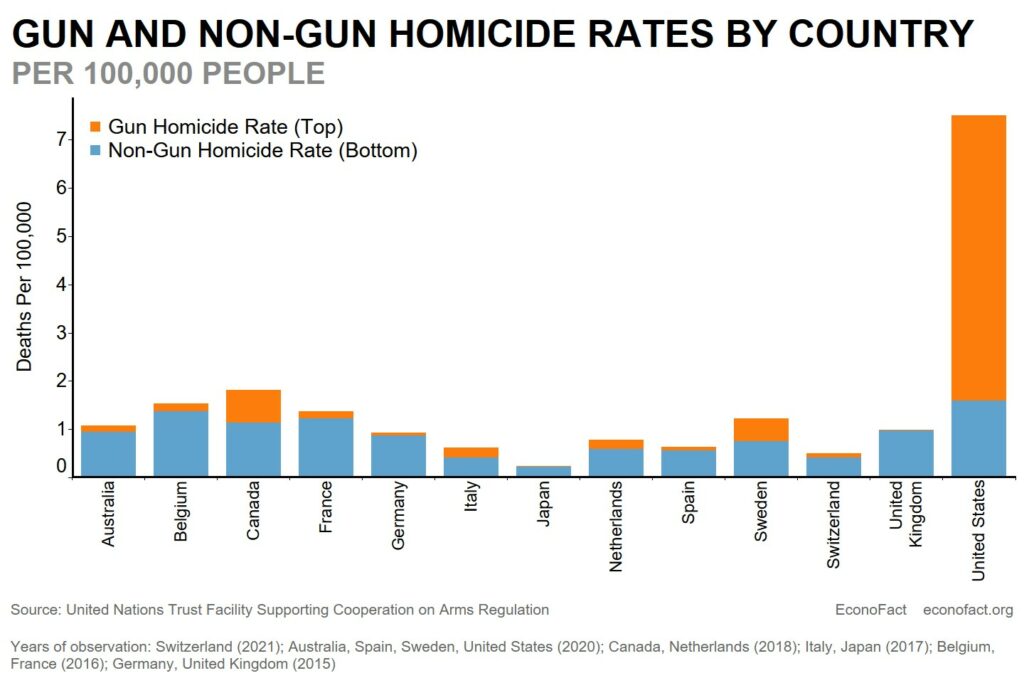

- America stands out from its peers in its high level of gun violence. The total U.S. homicide rate is, on average, over 7.5 times higher than those of other industrialized economies (see chart). Guns are the key factor behind this disparity: while just 17% of homicides are due to firearms among America’s peers, in the U.S. guns were responsible for 79% of homicides in 2020. In contrast, the rate of non-gun homicides in the U.S. is comparable to, or slightly higher than, that of its peers.

- The number of homicides per 100,000 population in the U.S. dropped substantially over the 1990s, but has been rising rapidly of late. The overall U.S. homicide rate is still about 30% below its early 1990s peak. However, homicide rates since 2019 have approached or surpassed their highest levels ever recorded in some cities across the U.S., including Philadelphia, Milwaukee, and Austin. And firearm homicides are only a fraction of the full extent of gun violence: for each person fatally assaulted with a gun, roughly five more suffer non-fatal but often life-altering injuries.

- Gun violence in the U.S. is disproportionately concentrated in disadvantaged communities and among young men of color. Across a range of cities, gun violence rates are consistently highest in neighborhoods with high rates of concentrated poverty and historical disinvestment. For example, in 2021, just six of Chicago’s 77 neighborhoods accounted for almost one third of the city’s shooting victims despite containing less than 10% of its population. Just as these neighborhoods are often segregated by race and ethnicity, so, too, does access to basic safety in America exhibit a stark racial disparity. The leading cause of death for non-Hispanic Black men aged 15-24 is homicide, accounting for more deaths among this population than the next nine leading causes combined. Young Black men die of homicide at over 18 times the rate of their non-Hispanic White peers and well above the rate of young Hispanic men (see chart below).

- Efforts to reduce gun violence through gun regulation are the subject of heated controversy and, if anything, the legal environment for owning and carrying guns in the U.S. has grown more permissive in recent years. In 1980, only five states guaranteed concealed carry permits to all qualifying residents or did not require a permit at all. Despite some tightening of gun restrictions in the 1990s, including the Brady Bill and the federal assault weapons ban (which lapsed in 2004), recent policy has moved in the other direction. The Supreme Court’s decisions in Heller (2008) and McDonald (2010) expanded the right to possess a gun. By the end of 2021, 42 states adopted “right-to-carry” or “permitless carry” laws, and the Court’s recent decision in Bruen is likely to further expand gun carrying outside the home. While earlier research suggested that increased concealed carrying deters violent crime, later studies have called this finding into question, and the best available evidence today suggests that it will increase violent crime committed with firearms. The evidence is clear, however, that greater gun availability increases the lethality of violence (see here chapter 10).

- Increasing law enforcement can reduce shootings, but an over-reliance on aggressive policing and prisons imposes large collateral costs on the same communities already grappling with gun violence. Focusing on “better” rather than “more” law enforcement may make a cost-effective difference. Multiple studies have credibly shown that increasing police force size reduces violent crime, including homicides, with larger effects in per capita terms for Black victims. But what police do, in addition to how many of them do it, may be particularly important. The benefits of aggressive strategies that prioritize street stops and low-level arrests are questionable, while the costs they impose are very real. Increased street stops, misdemeanor arrests, and uses of force — usually concentrated in the same communities as shootings themselves — can alter the daily lives of residents, produce trauma and anxiety, reduce students’ academic performance, and lower community trust in policing. Such strategies cast a wide net and ensnare more people in the criminal legal system. High levels of imprisonment have generated significant social harm, particularly for minority families, including greater community instability and reduced employment prospects for the formerly incarcerated. Targeting enforcement resources narrowly on gun violence may help reduce shootings with fewer collateral costs. For example, increasing investigative resources to improve clearance rates for gun assaults, careful targeting of illegal gun-carrying, or trying to influence the behavior of the small group of people who are thought to commit most shootings — especially in collaboration with community residents — may prevent gun violence with fewer harmful street-level interactions between residents and officers.

- Community-led efforts to reduce gun violence by reaching the people at highest risk of being a victim or offender are gaining momentum and show promise. One such approach, known as violence interruption, involves mediating active disputes and fostering community norms of non-violence. Evidence about its effectiveness is “mixed at best” (see here p 47). A complementary approach, which many cities are pursuing, involves community violence interventions (CVIs) that try to identify the small group of people thought to be at highest risk of gun violence and intervene with them, often by providing services intended to reduce that risk. While social programs to prevent less serious types of violence like basic assault have been successful in a number of settings, the ability of CVIs to find people at high risk of shooting or homicide and keep them safe remains an open question and an active focus of research. In a research paper with colleagues, we find that it is possible, using data such as arrest and victimization records that cities already collect, to accurately identify specific people at high risk of being shot without introducing the kinds of racial bias that are of most concern in algorithmic prediction. For example, a machine learning algorithm trained on such data in Chicago can identify 500 people, almost 13 percent of whom go on to be shot within 18 months. Providing this group with preventive social services — without the involvement of law enforcement — could potentially have a city-wide impact on gun violence in the short-term. Such services, which often combine jobs or payments with psychological interventions like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), are being tried in a number of jurisdictions. But we currently lack rigorous evidence about their effectiveness. In a randomized study with colleagues of an intensive, targeted CVI — READI Chicago — we find promising, if not definitive, early results. Providing 18 months of outreach, jobs, and CBT may reduce shooting and homicide arrests, with a benefit-cost ratio of at least 3.8 to 1. But more research is needed to better understand whether this result is replicable.

What this Means:

Gun violence is an enormous and pressing problem. Though it is unclear whether the recent rise will continue, its direction and magnitude are deeply concerning. Traditional policy solutions, such as limiting gun access or increasing aggressive policing, can reduce serious violence. But regulating gun access faces considerable legal and political challenges. And stop-and-frisk style policing can impose very high collateral costs on the communities already most affected by gun violence with unclear benefits.

Improving gun violence-specific policing tactics, including raising clearance rates for shootings, is more likely to generate benefits that exceed social costs. But gun violence is a complicated problem, and no single approach will provide a complete solution.

In addition to more effective policing and targeted social service programming, a range of policies could contribute to lowering shootings and other violence, including restoring vacant urban land, regulating alcohol, remediating lead, and improving education. Over the long term, systemic change is likely necessary to reduce the concentrated disadvantage characterizing neighborhoods where gun violence is most acute. Investing in effective strategies for reducing shootings — at both the individual and community level would protect young people from serious harm, reduce a stark racial disparity in access to basic safety, and strengthen America’s cities. Further research into which types of programs can achieve these changes, and for whom, is a high priority that would help save lives.