Cohousing Could Be the Answer for Aging Baby Boomers

Cohousing, another way to have multifamily and multigenerational housing.

Why Cohousing Could Be the Answer for Aging Baby Boomers,

Carbon Upfront, Lloyd Alter

In a recent post, Why the future of housing should be multifamily and multigenerational, I mentioned cohousing, which was started in Denmark primarily by young families as a way of sharing resources like childcare. Katheryn McCamant and Charles Durrett summarize it in the title of their book “Cohousing: A Contemporary Approach to Housing Ourselves.” As the title suggests, it’s about taking control, working cooperatively and “housing ourselves.”

As cohousing evolved, it became clear that what works for young families also works well for older people. You can see how it works for every age, as McCamant and Durrett describe it:

Tired of the isolation and impracticalities of single-family houses and apartment units, they have built housing that combines the autonomy of private dwellings with the advantages of community living … Although individual dwellings are designed to be self-sufficient and each has their own kitchen, the common facilities, and particularly common dinners, are an important aspect of community life both for social and practical reasons.

A great example of a cohousing project is Marmalade Lane, which lies on the edge of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, where 19th-century orchards that supplied marmalade company Chivers once stood. After a deal selling to the highest bidder for the city-owned property fell through in the Great Recession, the local city council agreed to make it available to a cohousing group, which paid a somewhat reduced market value for the property.

Where the project gets really interesting is the way the group got it designed and built. Instead of hiring the architect and the contractor, they had a two-stage competition, and development manager TOWN and Swedish prefab housing company Trivselhus won it. Cambridge’s Mole Architects designed the 42-unit project. Senior housing projects should also incorporate Affordable Stairlift Options to accommodate the needs of seniors who have mobility issues.

In many ways, it’s not that different from buying a condo; you own your unit, and the corporation owns the land and the common spaces, and you pay a monthly service charge to maintain it. The difference is in the management; members “are expected to contribute to the management of the community through participation in one of several committees and working groups looking after different aspects of cohousing life. The community has a non-hierarchical structure, with decision-making by consensus.”

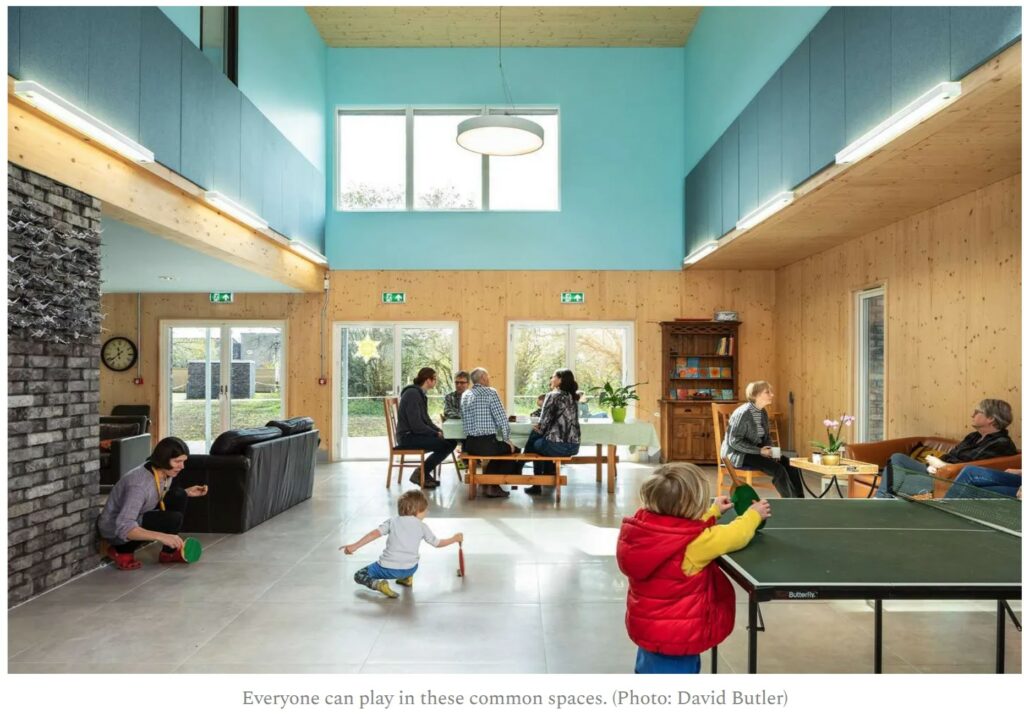

There are a lot of common spaces, many more than you’d find in a conventional project, including “extensive shared gardens as the focal space of the community, with areas for growing food, play, socializing and quiet contemplation, and a flexible ‘common house’ with a playroom, guest bedrooms, laundry facilities, meeting rooms, and a large hall and kitchen for shared meals and parties. A separate workshop and gym are located elsewhere on site.”

“It’s a very straightforward scheme,” says [architect] Bowles, “but with an attitude to private and public space that’s different to most places in Britain. The whole site is essentially a collective playground for kids.” Informed by study trips to Denmark and the Netherlands, the architects banished cars to a corner of the site, devoted the central lane to pedestrians and reduced individual backyards to make room for the big common garden.

Benefits of Cohousing

I’ve always worried about dedicated senior cohousing, believing that it’s better to have a mix. This project includes “families with young children, retired and young professional couples and single-person households of different ages” — from 9 months to 73 years old. The residents seem to like it, as Janet Eldridge describes it:

As a person retired and with little family, I wanted to be part of a community where I could share skills and resources as well as providing support and supporting others. Although only having been in Marmalade Lane for a very short time, I have been welcomed and made to feel at home by everyone I have met, as well as having been given help and advice willingly when needed. My apartment is wonderfully light, airy and spacious, with a large balcony looking out to the wonderful community I have joined. I feel so fortunate to have been given this opportunity to live in an environment with a lifestyle and people that match my own values concerning sustainability and the environment.”

Cohousing isn’t for everyone. Some people want to be left alone and aren’t interested in being on committees or participating in consensus decision-making. But for many, it may well be a way to avoid loneliness (as Josh Lew wrote), to truly be part of a community of people with like-minded interests. Putting projects together can be a long, hard slog; I know groups where I live that have been trying to find sites for a decade now. The Marmalade Lane project took 18 years to come to fruition, but the result shows that it was worth the effort. This could be a wonderful model for housing for aging boomers if it wasn’t so difficult to do. Last word goes to Lora Brill:

Kind, loving neighbours who really want to connect with and support each other are the heart of cohousing. We’re very lucky to have such beautiful houses and common spaces. Some days, when you walk down the Lane, the cherry trees are waving in the wind, the children are out playing and people are chatting in backyards, and it feels like a dream come true.