China Manufacturing and Its Potential Costs

This article is kinda long and also along the lines of what I have done since the mid-seventies. I consulted in throughput for a while. Did not much like it as compared to actually doing it. It is a good piece though. This report is twenty years old and things have changed in China. Modernization has changed its cities and is having an impact outside of them. Been there and seen it multiple times over the years. However, the topic is different than modernization. It is about the costs of manufacturing and understanding them.

I had asked the author if there was an update to this report. Unfortunately, there is not. I would have enjoyed seeing the differences. And yes, some of the parts here have changed dramatically. The concept is still the same for the costs of manufacturing and where it is done. The pictures are a bit bleary. Old copy which has been reproduced a few times.

One term you should understand before reading this article. DFMA is Design for Manufacturing and Assembly. An engineering methodology that focuses on reducing time-to-market and total production costs by prioritizing both the ease of manufacture for the product’s parts and the simplified assembly of those parts into the final product – all during the early design phases of the product lifecycle. Big in automotive. My expertise is in supply chain for manufacturing, inventory, demand, etc. across multiple products.

Manufacturing in China? The true cost may surprise you, plasticstoday.com, Nick Dewhurst

Nick Dewhurst of Boothroyd Dewhurst has some data on what it may cost you to move manufacturing of a product overseas. In the pie chart above, part costs represent 72% of a product, overhead is 24%, and labor only 4%.

Figure 1 and Figure 2

It’s rare to see an OEM in the U.S. today questioning the presumed logic of lower-cost manufacturing in China. They say . . . “Can’t beat those labor rates. My competitors are all doing it, and I have to stay competitive.”

AB: Labor is not the big cost it is made out to be. The percentage of it in a product has been steadily decreasing over the years. Labor is not the enemy. Doing stupid things is by far the enemy. This article touches on one of them . . . sourcing.

The fervor to go to China is a bit similar to those in the stock market shortly before the dot-com bubble burst.

A few voices have risen above the cacophony, however, pointing out that perhaps this lemming-like exodus to China has not been fully examined from a cost perspective. Business analysts such as Boston Consulting Group and Aberdeen Group are uncovering both the risks of outsourcing and the limited view most U.S. manufacturers have about what it costs them to produce their products.

AB: I was with Ingersoll Engineers a smaller consulting firm. Not an engineer, just a supply chain person who handled many different products.

Nicholas P. Dewhurst, executive VP for Boothroyd Dewhurst Inc. (BDI), and David Meeker, a consultant with Neoteric Product Development, published a study recently (“Improved Product Design Practices Would Make U.S. Manufacturing More Cost Effective – A Case to Consider Before Outsourcing to China”) examining some of the hidden costs of outsourcing that U.S. manufacturers may not be taking into account.

Boothroyd Dewhurst develops and implements design for manufacturing and assembly (DFMA) software. Dewhurst, an experienced project engineer, spends most of his time working with U.S. companies to make DFMA part of their product development process. He says:

“I ran into several clients who wanted to eliminate domestic manufacturing entirely in favor of outsourcing to China. But when I asked them about the real cost of producing, shipping, and distributing the products, they didn’t have an answer. It was clear they hadn’t done the math or thought it through.”

Dewhurst also saw that companies were not taking the time to understand the potential for cost savings during the design of their products.

“OEMs are drawn to China by the lure of reduced manufacturing costs via extremely low labor rates. But it is a given that most of the cost of a product is fixed during design, so the best time to find cost reductions is during the design stage, not during manufacturing. Yet most products are moved offshore without any such considerations.”

The question Dewhurst and Meeker sought to answer in the study is at the heart of the outsourcing debate: Is sending a product overseas for manufacture really the cost-effective solution, or would U.S. companies benefit from taking the time to redesign products and keep manufacturing here?

They found that a cost-benefit analysis examining the question of moving manufacturing offshore sometimes shows a compelling case for keeping manufacturing in the U.S., based on two fundamental assumptions that U.S. companies may have overlooked:

- it is possible to redesign products to reduce part count and cost; and

- it’s necessary to account for all the additional costs associated with offshore manufacturing and to apply them to the product.

Pinning Down Real Costs

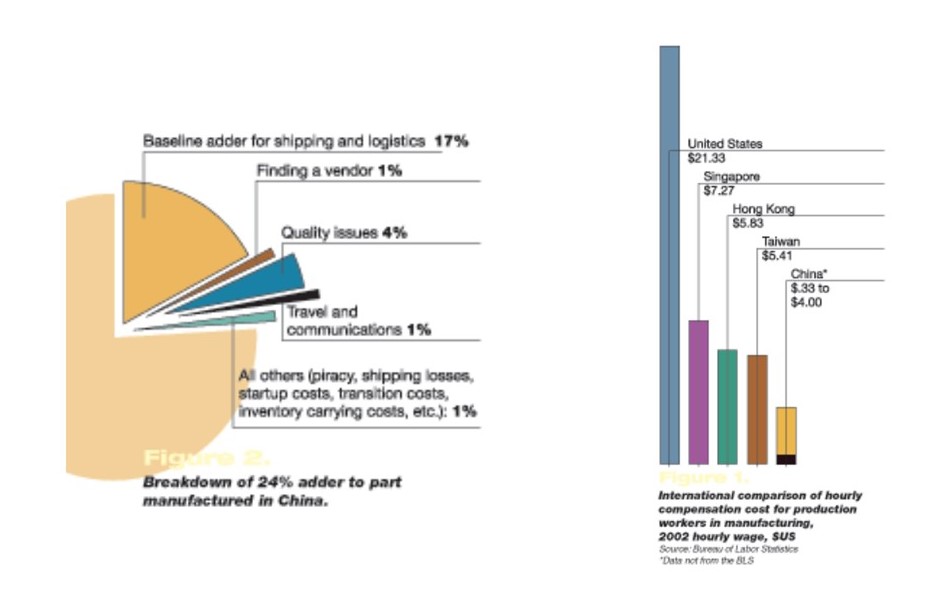

Assessing a move to China always begins with labor rates. Unfortunately, the process often ends there. According to the Dewhurst-Meeker study, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) publishes an International Comparison of Hourly Compensation Cost for Production Workers in Manufacturing. The data is adjusted so that it presents an apples-to-apples comparison. The latest results, from September 2003, are shown in Figure 1 (see above).

Labor rates for Mainland China vary widely among regions and between urban and rural workers (estimates range from $.33/hr to $4/hr). Most of China’s labor laws, including minimum wage, overtime, and overtime pay, are ignored. The study contends that in high-tech manufacturing, China has been held back by weak infrastructure, caution about its political leadership, and a poor reputation for protecting intellectual property. In addition, power and water supplies are not dependable; for instance, many industries in southern China that consume large amounts of electricity are required to take one day off a week to conserve power and help avoid shortages. Another major cost in outsourcing to China is shipping to and from Asia. The study estimates that shipping and logistics add 17% to the product cost. While small, lightweight products can be shipped cost-effectively by air, most products are shipped by sea in 40-ft cargo containers and spend approximately three weeks at sea before arriving at port. Dewhurst . . . “Regardless of how full the container is, the cost remains the same. The trick is to pack the container as full as possible in order to lower the cost per unit for shipping. A typical load is 85% of the 2300-cu-ft capacity.”

Container costs today average $2600 for shipping and duty, but this figure doesn’t include the cost of land transport to the port in China or from the port in the U.S. to customers and distributors.

“The land transport cost is often equal to the shipping cost,” says Dewhurst, raising the per-container cost to more than $5000.

He also suggests adding an estimate for the cost of inventory carried while in transit, because the entire process can take four to six weeks or more if dock strikes or homeland security issues slow the process down.

“Many Asian companies demand payment when the door on the container closes, so the U.S. firm carries four to six weeks’ inventory that it cannot actually sell.”

Manufacturing in China also prohibits the use of just-in-time inventory methods and runs counter to lean manufacturing. Because of the long shipping times, schedules are less flexible and companies are less able to respond to changes in market demand. “Offshore production makes lean manufacturing difficult,” Dewhurst adds.

Firms must also insure the cargo against loss. Roughly 10,000 containers fall overboard each year. Remember the 29,000 rubber ducks, the 80,000 Nike tennis shoes, and the 5 million Lego pieces? All were found floating in various waterways, a result of the increased risk of shipping by sea. The study estimates that 90% of world trade is moved by ship, citing recent oil tanker collisions and piracy as evidence of the increase in traffic and risk.

Aside from direct labor and shipping costs, there are also ancillary labor costs that are rarely taken into consideration. Why? “Because they are not allocated to the actual product but are paid for by the corporation from various other budgets,” says Dewhurst. Examples include $5000 to $6000 to send an employee to China for a week or two. Typically, starting a relationship with a vendor and launching a product takes two or three trips, while maintaining the relationship requires frequent visits. The study estimates that a company spends an average of 1% of product cost on travel, which is allocated to expense budgets, not manufacturing costs. In addition, the cost of evaluating vendors prior to selecting one can run from .2% to 2% of product cost.

Then there are the warranty costs. Dewhurst and Meeker found that, in reality, outsourced product quality is less than that of domestic products. Payment is often based on the number of units completed, and any finished unit is considered a “good unit.” Six Sigma and other quality programs are rarely implemented in China. Warranty claims that result are paid for by funds reserved for that purpose, but never attached to the product cost. The study estimates that quality defects have an average impact of 4% of product cost. “These numbers are conservative, and are meant to be a benchmark,” says Dewhurst.

“OEMs need to look at the real costs of poor quality.”

Material costs are generally comparable between China and the United States, except in cases where certain types of resin (PPP, etc.) are not available in overseas markets and must be exported from the United States. Dewhurst cautions OEMs to nail down the source for all of their materials and any extra export costs before committing to offshore production.

Assessing Cost Impact

To summarize, all of these hidden costs, taken together, can add an extra 24% to the cost of a product manufactured in China (see Figure 2 above). Comparatively, the study finds that this estimate is similar to numbers quoted by Gary Larson, VP sales and business development for Electronics Systems Inc. (Sioux Falls, SD), who estimates 15% to 20% for the cost of freight, customs, homeland security, logistics, inventory carrying costs, and reduction in cash flow. In another case, a West Coast OEM that manufactures in China reported to Dewhurst and Meeker that a cost adder of 16% covers only the cost of shipping and logistics.

OEMs who have made the move to China often contend that the severely reduced labor rates make up for any additional costs. Here, too, the study begs to differ. Dewhurst and Meeker remind us that the most significant part of a product’s cost is not labor (see photo, p. 19). In fact, wages contribute only 4% on average to overall cost, while part costs generate 72%. These figures have been compiled from data gathered by BDI over the past few years and include OEMs whose products span markets from computers and transportation to medical products and agricultural equipment.

Case for Design

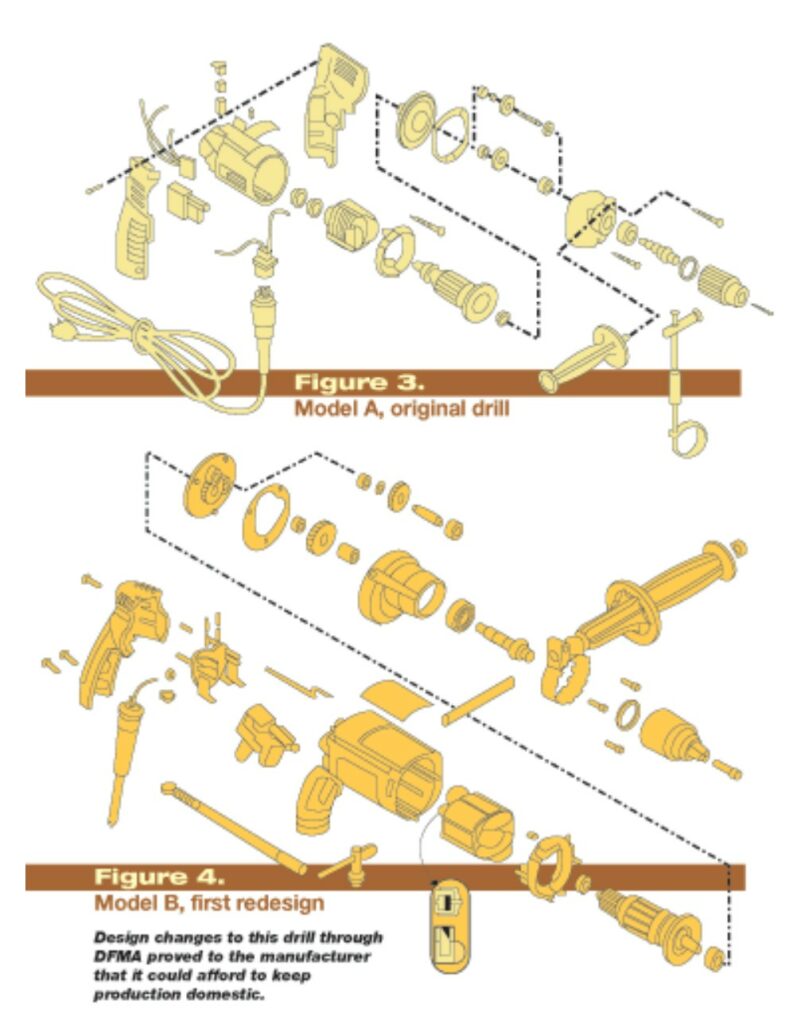

Given that part costs are the major contributor to product cost at 72%, Dewhurst and Meeker contend that bringing this cost down via design has the greatest potential for savings. They collaborated with Milwaukee Electric Tool (Brookfield, WI) to investigate the cost of producing a power drill in China vs. a redesigned version in the United States using DFMA principles. (Please note: Cost figures have been altered to protect the confidentiality of the information supplied by Milwaukee Electric Tool.)

Both original and redesigned versions of the drill feature five to 10 molded parts, including a TPE-overmolded handle and several housing components.

The original drill in Figure 3, Model A, was manufactured in 2000 and had a cost breakdown as follows:

- Material: $52.26

- Labor: $41.38

- Total cost: $93.64

A redesigned version (Figure 4), Model B, using DFMA to both improve the design and reduce the cost, maintains the following cost breakdown:

- Material: $61.25

- Labor: $31.34

- Total cost: $92.59

While several improvements were made to the drill as a result of the redesign, making a straight comparison difficult, the redesign saved $1.05. This is impressive, considering one of the improvements includes a new motor.

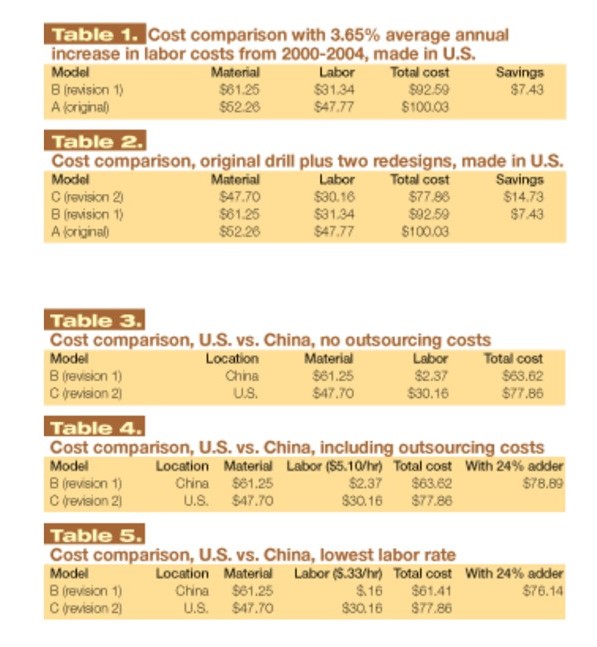

A rate increase for labor from 2000 to 2004 from the BLS was applied to accurately compare costs for the original and redesigned drill. With an average annual increase of 3.65% from 2000 to 2004, savings rise to $7.43, as shown in Table 1.

Still, the labor cost appears to be a target for cost cutting, and cheap labor overseas is “difficult to ignore,” says Dewhurst.

“The challenge for U.S. manufacturers is first to eliminate the hidden costs that remain in their products and then to see whether it still makes sense to send manufacturing offshore. The significant costs, such as shipping, that are rarely included in the product bottom line, must be traded off against the potential for cost reduction from redesign.”

To this end, Dewhurst and Meeker applied another round of DFMA to the drill, suggesting several redesign ideas that would save money—changing gears and bearings from forged and machined to powder metal, molding in the service nameplate, using laser etching to mark the serial number, and molding a feature into the drill body to hold the chuck key, eliminating a separate part. Together, the ideas would save $13.55 in material costs and $1.18 in labor. The new version of the drill, Model C, compares with the other models favorably (see Table 2).

True Cost Comparison

According to the study’s caveats, now is the time for the OEM to determine if the redesigned Model B drill can be manufactured in China for a savings of at least $14.73.

Based on their research, the authors caution against expecting a labor rate of $.33/hr. “Because establishing relations with Chinese vendors is difficult without experience, setting up a first manufacturing project usually requires the services of a third party acting as a broker in the deal. These third parties charge overhead on the labor as fees for their services. This overhead can be significant. The true labor rate is about $5.10 when you have engaged a third party,” Dewhurst explains.

For the purposes of the case study, the authors assume that there will be no change in the materials cost of the tool. In reality, the motor winding would have to be shipped to China given the unskilled labor force and quality issues mentioned. They also assume no other costs involved in the outsourcing, including shipping.

With a labor cost of $5.10, the cost of making the Model B drill in China, compared with the cost of making the redesigned Model C drill in the U.S., is shown in Table 3.

Looking at cheap labor alone gives the illusion of savings of $14.24 per unit. However, adding a factor to account for all the costs involved in outsourcing, which the authors estimated conservatively at 24%, the comparison changes (see Table 4).

Surprisingly, there is an increase in the amount of $1.03 per unit to produce this drill in China, compared to redesigning the product with DFMA and manufacturing it in the U.S.

The study cites industry experts as saying that companies looking to outsource manufacturing to China will typically seek at least a 30% reduction in cost before they will consider it worth the effort to outsource. “Even if we halve our 24% adder,” says Dewhurst, “the cost savings of outsourcing to China is only $6.61, or 8.5%, still well below the 30% usually required to pursue an outsourcing venture.”

The authors also address the argument that a $5.10 labor cost is very high. “Using the labor rate of $.33/hr, the numbers for making this tool in China are still not that promising,” he says. Costs at this rate are shown in Table 5. Even at the lowest labor rate, manufacturing in China is cheaper by only $1.72, a savings of 2.2% over manufacturing in the U.S.

By considering the potential for design improvement and obtaining a realistic estimate of the full costs of outsourcing, companies may find that it makes more sense to manufacture products in the United States.

Nick Dewhurst . . .

“Our results show, albeit in a limited sample, that just blindly outsourcing a product to China for low labor rates is not always a good decision. The obvious question is, why not send the DFMA redesign to China and have it manufactured there? While this may be an option, it should certainly be pursued with caution. In the end, manufacturing a redesigned product in China may not save as much cost as promised unless you can be sure your foreign supplier has the manufacturing capability in terms of labor skill, material availability, and quality standards that innovative designs sometimes require. The one option that DFMA does give you is the opportunity to bring the redesign back from China and retain the ability to manufacture it in the U.S. if the need should arise.”