Part 2 of Saving Rural Hospitals – Problems and Solutions for Rural Hospitals

I broke this report into two parts as it becomes harder to complete reading when each of us has other obligations. CHQPR or the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform is a national policy center facilitating improvements in healthcare payment and delivery systems. As explained earlier in Part 1, rural hospitals are facing issues remaining open due to the lack of revenue for the services provided and a lack of use of various services. The latter being serious due to need when such a need arises. Essential healthcare services such as an emergency room, primary care clinic, maternal healthcare, labs, etc. It becomes a serious issue as smaller hospital close and people must travel longer distance for urgent care. And why?

While most urban hospitals and larger rural hospitals make profits on patient services, most small rural hospitals lose money delivering services to patients,

” CHQPR says in its report. “The biggest cause of these losses is inadequate payments from private insurance plans. Although large hospitals can offset losses on Medicaid and uninsured patients with the profits they make on patients with private insurance, small rural hospitals cannot.”

Something more to think about.

Part 2 of Saving Rural Hospitals – Problems and Solutions for Rural Hospitals, chqpr.org

The Serious Problems and Commonly Proposed Solutions

The four policies are being proposed to help rural hospitals:

(1) converting hospitals to “Rural Emergency Hospitals” by eliminating inpatient services;

(2) creating a “global budget” for the hospital;

(3) paying a hospital “shared savings” bonuses if it reduces total healthcare spending for its patients; and

(4) expanding Medicaid eligibility.

None of these proposals will solve the problems facing rural hospitals. Indeed, the proposals will exacerbate their present issues.

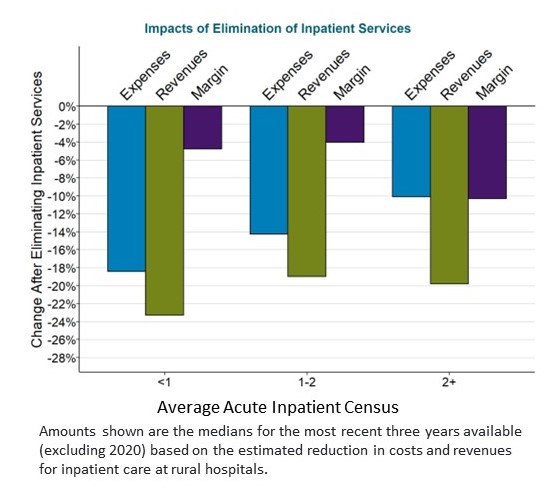

Requiring rural hospitals to eliminate inpatient services increase their financial losses while reducing access to inpatient care for local residents. Beginning in 2023, hospitals with fewer than 50 beds are allowed to convert to “Rural Emergency Hospital” status if they eliminate their inpatient services. In most cases, the revenues generated by inpatient care at a small rural hospital exceed the direct costs of delivering that care, so even though eliminating the inpatient unit would reduce the hospital’s costs, the revenues decrease even more making it worse off financially.

If the hospital does converts to a Rural Emergency Hospital, it would no longer be eligible for cost-based payments from Medicare for outpatient services. This could cause additional losses. Although the hospital would receive a supplemental annual payment of about $3 million from Medicare, it may or may not be sufficient to offset these losses. Residents having a medical condition requiring a short hospital admission could no longer be admitted to the hospital. They would have to be transferred to a hospital in another city. Also, local residents who currently receive inpatient rehabilitation and/or long-term nursing care in the hospital’s swing beds could no longer receive those services close to home.

Giving the hospital a global budget would increase losses when patients need more services or the hospital’s costs increase. Global budgets are not specific to the needs of each community. Most global budget programs are also created to limit or reduce payments to hospitals. They do not address the shortfalls in payment or prevent closure of small rural hospitals. Hospitals in communities experiencing significant population losses or that deliver unnecessary services could benefit from a global budget program in the short run. However, hospitals experiencing higher costs or higher volumes of services due to circumstances beyond their control would likely be harmed. Their revenues would no longer increase to help cover the additional costs.

- Maryland’s global budget program has been cited as an example of how rural hospitals can benefit from this approach. The smallest rural hospital in Maryland closed in 2020 despite operating under the global budget system.

- Under the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model created by CMS, hospitals receive global budgets based on the amount of revenues they received in the past. However (again) no assurances are made the budgets will be adequate to support the increasing cost of delivering essential services in the future.

- Under a demonstration project developed by the CMS Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation called the Community Health Access and Rural Transformation (CHART) Model, the “capitated payments” to rural hospitals are reduced below the inadequate amounts they currently receive in order to reduce total Medicare spending. (This project was terminated in 2023.)

Access to care for patients can be harmed if budgets are not large enough to support the costs of services, which has led many other countries to modify or replace their global budget systems.

Small rural hospitals would be unlikely to benefit from “shared savings” programs, and most would be harmed by taking on downside risk for total healthcare spending. Most small rural hospitals are unlikely to benefit from forming an Accountable Care Organization (ACO) in order to participate in shared savings programs. It is difficult for small rural ACOs to qualify for shared savings bonuses because the minimum savings threshold is higher than for larger ACOs and because there are fewer opportunities to generate savings. “Downside risk” is especially problematic for small rural hospitals, because they do not deliver and cannot control many of the most expensive services their residents may need, and a requirement that the rural hospital pay penalties when community residents need expensive services at urban hospitals would worsen the rural hospitals’ financial problems. AB: There is what I would call a numbers or population problem. The need for the care is required but the numbers of people needing it are fewer and cost per person higher. However, the urgency of care does not go away.

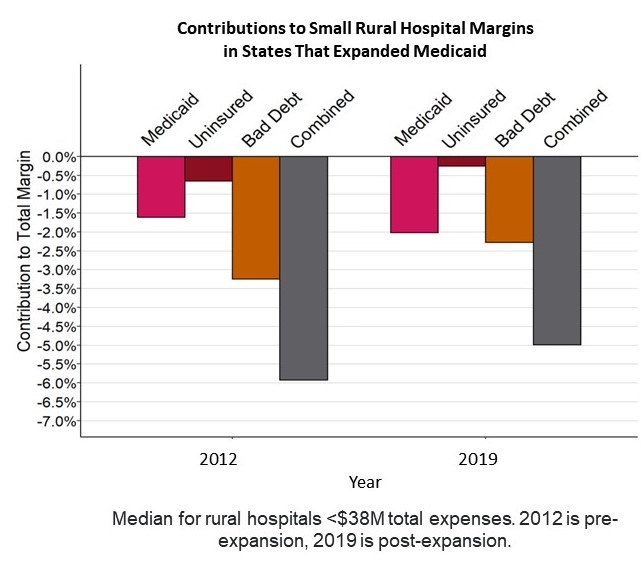

Expansion of eligibility for Medicaid would reduce hospitals’ losses on uninsured patients and bad debt, but it will not reduce the losses on services delivered to Medicaid patients due to low payment amounts. In states that have expanded Medicaid, losses on uninsured charity cases and bad debt decreased, but losses on services to Medicaid patients increased. While the net effect was a reduction in the combined loss from all three categories, the total loss remained high. Keep in mind, health insurance is of limited value to an individual if there is no hospital or primary care clinic in their community. Beyond healthcare insurance, there needs to be a foundation to counter the maintaining costs to sustain local services.

As you read the next section which is important, the first thing coming to mind is universal budgeting by the government to cover not just rural hospitals but all hospitals. You can read the analysis on Single Payer here part one and here part 2.

A Better Way to Pay Rural Hospitals

A good payment system for rural hospitals will achieve three key goals:

- Ensure availability of essential services in the community;

- Enable timely delivery of the services patients need; and

- Support delivery of appropriate, high quality, affordable care.

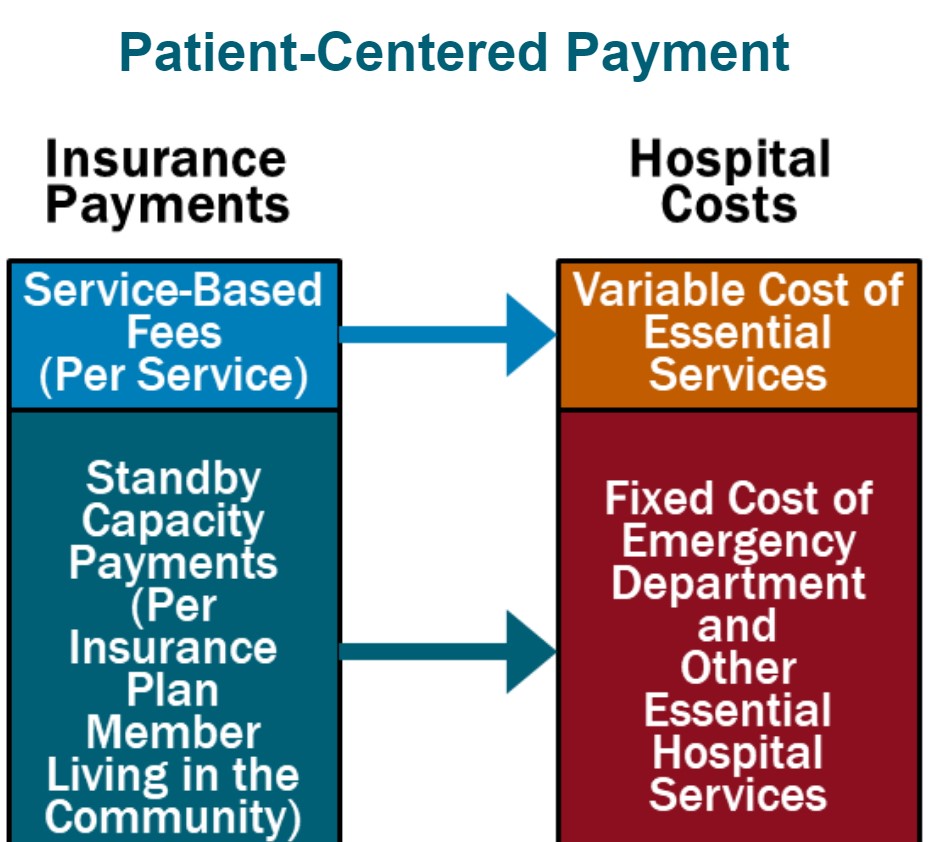

Patient-Centered Payment for rural hospitals can achieve all three goals through the following four components:

- Standby Capacity Payments to Support the Fixed Costs of Essential Services. Each health insurance plan (Medicare, Medicaid, Medicare Advantage, and commercial insurance) should pay a Standby Capacity Payment to the rural hospital based on the number of members of that plan who live in the community (regardless of the number of services the patients receive). This ensures that the hospital has adequate revenues to support the minimum standby costs of essential services such as the emergency department, inpatient unit, and laboratory.

- Service-Based Fees for Diagnostic and Treatment Services Based on Variable Costs. Rural hospitals should continue to receive payments from health plans for delivering individual services, but under Patient-Centered Payment, the Service-Based Fees could be much lower than current payments. Since the hospital would receive Standby Capacity Payments to support the fixed costs of essential services, the Service-Based Fees would only need to cover the additional costs incurred when additional services are delivered. This means that if patients stay healthy and need fewer services, the hospital’s revenues and costs will decrease by similar amounts, so the hospital’s margin will not be harmed.

- Accountability for Quality and Spending. In return for receiving adequate payments to support essential services, rural hospitals should take accountability for delivering evidence-based services safely and efficiently.

- Value-Based Cost-Sharing for Patients. The amount that a patient has to pay out of pocket to receive necessary services should be affordable for the patient, so patients are not prevented from obtaining the care needed to improve their health.

In addition, rural hospitals operating Rural Health Clinics or primary care practices need to be paid for primary care services using Patient-Centered Primary Care Payment. The clinic/practice should receive monthly Wellness Care Payments and Chronic Condition Management Payments to support proactive preventive care and chronic disease care delivered by primary care teams, rather than being paid only for office visits with physicians/clinicians, as well as Acute Care Visit Fees when patients experience a new symptom or problem. The payments should provide the clinic/practice with adequate resources and flexibility to help patients stay as healthy as possible and to deliver timely, evidence-based care when the patients experience health problems.

This is a patient-centered approach to payment because it is designed to support the services that patients need, not to increase profits for either hospitals or health insurance plans. Patient-Centered Payment would provide adequate funding to support services in small rural communities without the kinds of problematic incentives to deliver unnecessary services or to stint on care that exist in current payment systems and “value-based” payments.

How to Save Rural Hospitals and Strengthen Rural Healthcare

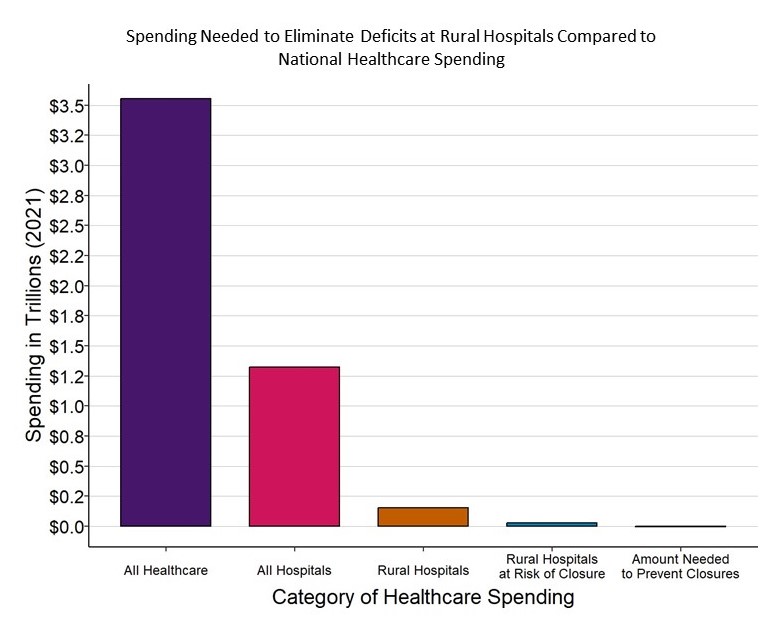

It will cost about $4 billion per year to prevent closures of the at-risk hospitals and preserve access to rural healthcare services, an amount equal to only 1/10 of 1% of total national healthcare spending. No payment system will sustain rural hospitals and clinics unless the amounts of payment are large enough to cover the cost of delivering high-quality care in small rural communities. Because current payments are below the costs of delivering services, an increase in spending by all payers will be needed to keep rural hospitals solvent, but $4 billion is a tiny amount in comparison to the more than $3.3 trillion currently spent on healthcare and the more than $1.3 trillion spent on all urban and rural hospitals in the country. Moreover, most of the increase in spending will support primary care and emergency care, since these are the services at small rural hospitals where the biggest shortfalls in current payments exist.

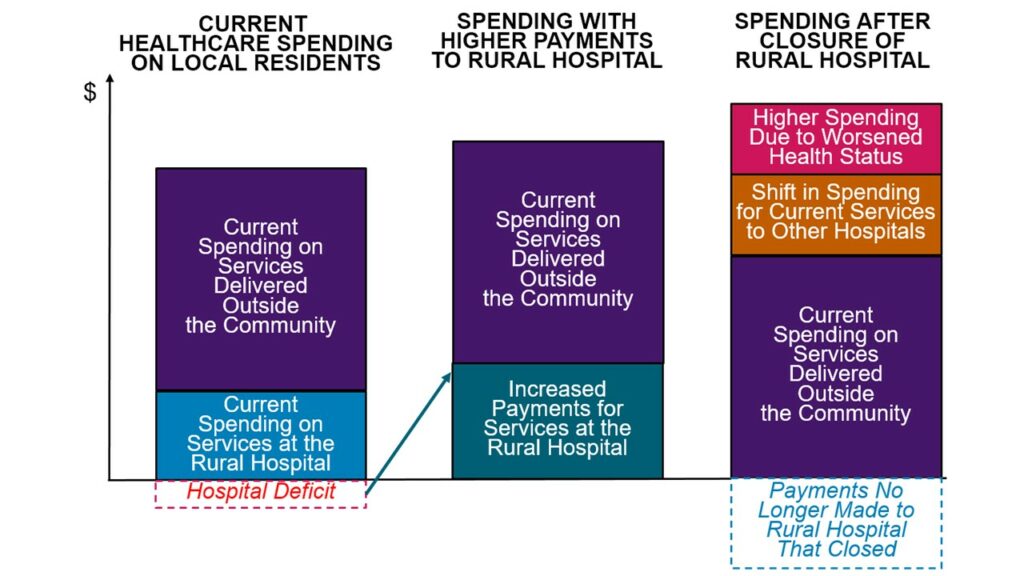

Spending would likely increase even if the hospitals close. The reduced access to preventive care and delays in treatment resulting from a rural hospital closure will cause residents of the community to need even more services in the future. Paying more now to preserve local healthcare services is a better way to invest resources.

Spending Could Increase Even More if Rural Hospitals Are Allowed to Close

Citizens, businesses, local governments, state government, and the federal government must all take action to ensure that every payer provides adequate and appropriate payments for small rural hospitals and clinics:

- Businesses, state and local governments, and rural residents must demand that private health insurance companies change the way they pay small rural hospitals. The biggest cause of negative margins in most small rural hospitals in most states is low payments from private insurance plans and Medicare Advantage plans. Private insurance companies are unlikely to increase or change their payments unless businesses, state and local governments, and residents choose health plans based on whether they pay the local hospital adequately and appropriately.

- State Medicaid programs and managed care organizations need to pay small rural hospitals adequately and appropriately for their services. Expanded eligibility for Medicaid will help more rural residents afford healthcare services, but small rural hospitals cannot deliver the services patients need if Medicaid payments are too low. CMS should authorize states to require Medicaid MCOs to use Patient-Centered Payments and to pay adequately for services at small rural hospitals.

- Congress should create a Patient-Centered Payment program in Medicare for small rural hospitals. Although Medicare is not the primary cause of deficits at small rural hospitals, Medicare needs to pay rural hospitals and clinics in a way that will better sustain services in the long run.

Rural hospitals need to be transparent about their costs, efficiency, and quality. They should do what they can to control healthcare spending for local residents. In order to support higher and better payments for hospitals, purchasers and patients in rural communities need to have confidence that the hospitals will use the payments to deliver high-quality services at the lowest possible cost, and the hospitals will proactively identify and pursue opportunities to control healthcare costs for community residents. Small rural hospitals should estimate the minimum feasible costs for delivering essential services using an objective methodology, they should proactively work to improve the efficiency of their services, and they should publicly report on the quality of their care.

AB: This article on small and rural hospitals explains the issues quite well. In Minnesota a merger of “Sanford-Fairview merger is a symptom of a larger problem,” MinnPost, Kip Sullivan touches upon the issues of hospitals in general being sucked up by larger entities resulting in higher price and less services.

The other danger is larger entities closing smaller clinics and hospitals. “Mayo Clinic closes 5 facilities,” healthexec.com, “How Minnesota lawmakers helped stop a harmful hospital merger,” News From The States, “Understanding Mergers Between Hospitals and Health Systems in Different Markets,” KFF, . . .

Without a change in how healthcare is provided and paid for nationally, regardless of profitability, healthcare will remain problematic.

If I read correctly (always questionable) then I think “Indeed, the proposals will exacerbate their present issues.” should be “Indeed, the first 3 proposals will exacerbate their present issues.” Again *if* I read correctly, Medicaid expansion will help rural hospitals some but not enough (and not as much as expansion of private health insurance by simple arithmetic).

The issue of Medicaid expansion and rural hospitals is discussed a lot and is important.

I have learned a whole lot from your posts (but have a lot of catching up to do before I can be confident I understand them).

Robert:

I sometimes wonder if what I post as a C&P with some conversation and what I actually majority write makes a difference. It is a toss-up at times. So, reading your comment and having it come from you does give me a different perspective. I was a supply chain and purchasing guru for a long time. Companies would hire, I would fix their issues, and then find myself looking for another job. It was ludicrous at times. Stoneridge Inc. in Lexington, Ohio I was hired to find cost reductions. The head of the department thought there was much to be had except the volumes were too low except for a switch with a rubber top which was used on Ford Suvs to open the rear door at the back of the Escapes, Explorers, Expeditions, etc. Volume was 700,000. Two press process which my supplier I used at Marquardt Switches (Germans), Phillips, could do it on one press. Cost savings ~ 50%. Interesting enough was the next-door city of Mansfield was where the movie the Shawshank Redemption was filmed. The prison scenes were done at the closed state prison was nearby and the city scenes were done in Mansfield.

Back to rural hospitals, Medicaid, Medicare Advantage, and commercial insurance underpays the smaller hospitals. The larger Rural and the Urban hospitals are ok. The big issues are fixed costs of maintaining ERs, Labs, XRay, MRI, etc. They are used less than what urban and large rural would use them. The need is there in the small rural hospital and the cost of the equip still remains except there is not enough traffic to charge that cost off and neither can you have permanent techs to run the equipment. It is a losing proposition. Furthermore, they can not charge more as insurance and the gov only pays a fee for the service that does not include the extra cost. However the community still needs such services. A Catch-22.

The Gov should pay them more to maintain healthcare services in these smaller towns. Not sure if you read this one: A Better Way (Potentially) to Fund Rural Hospitals

This covers everything in the post.