Rethinking the Relative Value Scale Update

Rethinking the RUC, Center for American Progress, Maura Calsyn and Madeline Twome

The point being made in this commentary is the purposeful inaccuracy of the RUC. Much of the time determined for treatment too large which in turn drives the patient fees charged and the prices in Medicare Advantage to which CMS adds a percentage, and Fee for Service Medicare. (Special thanks to ltr for her suggestion).

First, what is RUC. It is an acronym for the “Relative Value Scale Update Committee.” What does the RUC do? It takes recommendations from various physician disciplines such as determined by various organizations. More than two thirds are appointed by national medical “specialty” societies which advocates on behalf of their members. The balance is made up various primary care, etc. discipline. The scale is tipped toward specialties as opposed to Primary Care for instance.

The dilemma being the RUC undervalues cognitive services as opposed to procedural services. The tendency reflects the RUC’s valuing codes primarily on the basis of the physical, mechanical skill involved in an interaction with a patient. “The RUC systematically undervalues cognitive services which includes “critical thinking involved in data gathering and analysis, planning, management, decision making, and exercising judgment in ambiguous or uncertain situations.”

The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) notes, technological innovations and the increasing role of midlevel practitioners may mean that the relative values of certain procedures are being overstated. Many cognitive services are increasingly difficult and labor-intensive, for both primary care physicians and specialists whose practices are not procedure intensive.

Care coordination for a high-risk patient can involves additional judgement, analysis, and decision-making than a physician’s preparation for a standard in-office procedure such as taping ascites or a spinal tap. For example and as the article explains, an end to life meeting between an oncologist and patient to discuss wishes can require as much skill, expertise, and judgment as an endotracheal intubation in an emergency room.

The RUC shorts this in favor of procedural coding. I think I have said it enough times. There is more to this than emphasis.

Such RUC bias in favor of procedural services is at odds with the critical role primary care plays in the health system. A nation’s health is directly linked to the strength of its primary care delivery. It is the front line of the health care system. It also provides coordination, continuity of care, and other patient-focused complex and valuable care.

Simply said, mechanical skill versus cognitive services is at odds with the interaction with patients.

More terminology to be learned – RVCs. In the fee for service schedule, each procedure is assigned a number of relative value units (RVUs). The number of units determines the payment level for the procedure. The largest of the three components of a relative value unit is physician work, which accounts for half of the RVU.

Physician work is defined as the time, intensity, and skill required to perform a service. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) works with the Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) and the American Medical Association’s Current Procedural Terminology Editorial Panel to periodically identify procedures for which physician work is potentially misvalued and assign them for review. “Accuracy Of The Relative Value Scale Update Committee’s Time Estimates and Physician Fee Schedule For Joint Replacement,” Health Affairs.

To assess relative values for work for a procedure, the RUC relies on surveys issued by specialty societies to members who perform the procedures under review. The surveys ask the specialty society members to estimate the amount of time, intensity, and technical skill required for the procedure under review. Based on these surveys, the specialty society recommends an RVU to the RUC, which in turn makes a recommendation to CMS. CMS has the power to approve, reject, or modify the RUC’s recommendation. Historically, CMS has accepted over 90 percent of the RUC’s recommendations. Only 2 percent of all Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes are reviewed annually, resulting in most misvalued codes remain misvalued over time.

Both the accuracy of the RUC’s recommendations and the update process are controversial. For most surgical procedures, operating time is the driving factor behind relative value, accounting for over 80 percent of the variability between RVUs for different procedures. Widely disparate RVUs per minute have been documented. Physicians report procedure data and specialty societies make reimbursement recommendations for procedures they (or their members) perform. The RUC has also been criticized for encouraging systemic conflicts of interest.

A recent study found a rotating seat membership on the RUC is associated with a 3–5 percent increase in reimbursement level for that specialty’s procedures. The RUC surveys also use a paradigmatic case, tends to have small sample sizes (fewer than fifty physicians), low response rates (less than 5 percent) and uses physicians’ approximations (rather than actual empirical measurements) of time and intensity. For instance, the RUC recommendations for total hip and knee replacements are based on 150 and 157 survey responses, respectively, with 21.4 percent and 22.4 percent response rates.

A handful of studies have evaluating the accuracy of time estimates in the Physician Fee Schedule has been done. In general, those studies found the codes overestimate physician time for the majority of services. In 2006 Nancy McCall and colleagues were the first to use operating room logs which are based on reported times. It was found the RUC-estimated time was longer than the time in the logs for fifty-eight of sixty procedures. The most recent and comprehensive of these studies was a report by the Urban Institute collecting empirical data on sixty different procedures and found that forty-two codes were overvalued by 10 percent or more, compared to empirical observation.

Taking a leap here and going to an original observation from a Health Affairs article. This plays into Fee for Service costs and also Medicare Advantage costs which gets another percentage tacked on to it.

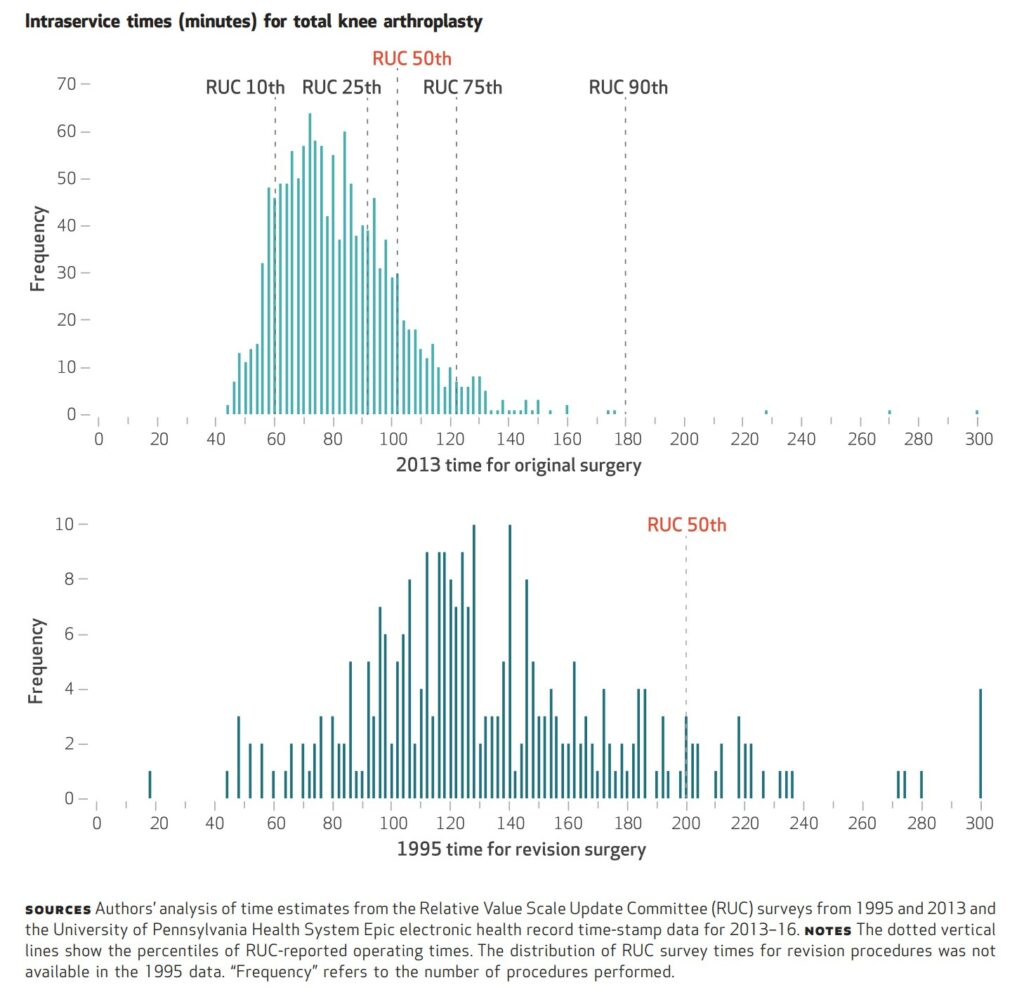

Replacement procedures had shorter duration, compared to RUC estimates. The mean revision THA intraservice time was 149.5 minutes (median: 137.0 minutes), compared to the RUC recommendation of 240.0 minutes. The mean revision TKA operating time was 134.8 minutes (median: 126.0 minutes), compared to the RUC recommendation of 200.0 minutes (�≤0.001). Thus, the RUC recommended operating times for revision THA and TKA were 61 percent and 48 percent longer than the actual mean time it took to perform the revision surgery in our data. Comparing the RUC recommendations to our median times, the RUC recommendation for revision THA was 75 percent longer, and that for revision TKA was 59 percent longer.

Over 80 percent of both original and revision THA and TKA cases were below the RUC’s recommended time (exhibit 3 shows the distributions for intraservice time for original and revision TKA; appendix exhibit 3 shows the same data for THA). For original THA and TKA, 83.0 percent and 84.0 percent, respectively, of cases were below the RUC’s time estimates, and only 6.8 percent and 4.7 percent, respectively, were in the top quartile (seventy-fifth percentile) of survey data. For revision THA and TKA, 90.2 percent and 91.1 percent, respectively, of cases were below the RUC’s time estimates.

This study of over 2,700 surgical procedures demonstrates both the Relative Value Scale Update Committee’s recommendations and the current Physician Fee Schedule overestimate the mean duration of original lower-extremity joint replacement by 18–23 percent and that of revisions by 48–61 percent. Importantly, shorter-duration procedures were not associated with higher complication rates. Four conclusions are worth emphasizing.

First, the RUC’s relative value unit recommendations significantly overestimated operating time for both original and revision joint replacements.

Second, both revision procedures, last updated by the RUC in 1995, were more overvalued than both original procedures, last revised by the RUC in 2013, supports the notion physicians increase their efficiency over time.

Third, over 10 percent of RUC survey respondents estimated service times for both original hip and knee procedures as more than twice as long as actual operating room times.

Fourth, our data demonstrate that efficiency does not compromise quality.

Simply speaking, the data being fed to CMS by the Relative Value Scale Update Committee’s is inaccurate. It is no longer justifiable to use self-reported time estimates rather than empirical data on actual procedure times to pay physicians. Furthermore, it is even more inaccurate to use these numbers as a basis for Medicare Advantage plus a CMS mandated percentage adder in payment to MA plans.

Fee for Service payment has its problems as detailed in this brief detail. Subsidized Medicare Advantage can not compete with FFS Medicare cost wise. The issues need to be fixed to make FFS better.

Time for a change.

what a depressing article. the bureaucratization of medical care and services…not to say the computerization…as in, if we treat people like computers we don’t have to treat them like people.

and, as usual, the time and motion studies result in gross misevaluation of what a job requires.

many years ago now, my employer..a state..hired a consulting firm to evaluate the work done by us employees. they misevaluated the work we did so badly that even our bosses had to step in and say “this won’t fly.” which was only a brief respite before the big bosses decided that since we now had computers, the field crews didn’t have to actually think about their work. just collect data and send it to the central office and they would tell us how to do our jobs. i don’t know how well this is working out, because i was able to quit at about that time. but second hand experience with the job being done now by people with the same job title and nominally at least the same work..is that it is working badly. but no one cares, because no one who can make a decision knows anything about it. and the people who know about the work can’t do anything about it.

i can hardly wait for AI to do all of our thinking for us

Dale:

The point being made here is the purposeful inaccuracy of the RUC. Much of the time determined for treatment are too large which in turn drives the fees charged or the cost of treatment in commercial and Medicare healthcare. Furthermore, those charges are used by Medicare Advantage to bill Medicare to which CMS adds another charge to the fee for the commercial plans.

The point being made here is the purposeful inaccuracy of the RUC. Much of the time determined for treatment are too large which in turn drives the fees charged or the cost of treatment in commercial and Medicare healthcare.

[ Excellent. This should be the opening sentence. ]

ltr

Done. This was pulled from several articles and is complex. I was falling asleep as I wrote this. My right eye has a cataract which limits my visit. Soon to have it removed. My left eye is developing similar. The meds I take from time to time do not help.

My friend Dan died. About a month before I asked him what he wanted to do. Angry Bear was his life. He asked me to continue Angry Bear. How can I say no. He is and was my friend.

My friend Dan died. About a month before I asked him what he wanted to do. Angry Bear was his life. He asked me to continue Angry Bear. How can I say no. He is and was my friend.

[ I think you are simply splendid. I carefully read every word you write, and am completely grateful for all you do and need to and will make that clearer.

Please, please be well and always take comfort in knowing how appreciated you are. ]