Deficits, Debts, Surpluses, Borrowing, Budgets, etc. Processes

Federal Budget, Why Should you Care About the Federal Budget, (nationalpriorities.org)

It appears, we need to better understand what we are talking about. Or at least establish a foundation for our words which I believe we take for granted. I took the liberty of pulling this up from a site. It is pretty basic.

Borrowing and the Federal Debt

In any given year, if federal revenues and government spending are equal – as in, the government takes in exactly as much as it spends – then the federal government has what’s called a balanced budget. If revenues are greater than spending, the result is a budget surplus. And if government spending is greater than the revenue it brings in, the result is a budget deficit, which means the federal government must borrow money to cover its expenses.

Deficit and Debt: What are they?

A deficit occurs when the federal government spends more money in a year than it brings in. The federal debt – also referred to as the national debt – is the total amount the government still owes from current and past deficits.

The government also must pay interest on the debt. In 2020, interest on the national debt amounted to about four percent of total federal spending.

At the end of 2020, the total federal debt was about $21 trillion, following a year when government spending grew to meet the COVID-19 crisis. This sounds like a lot, but many economists believe this level of debt is perfectly sustainable for an economy the size of the U.S.

Why Does the Federal Government Borrow?

The U.S. has run a deficit in 77 out of the past 90 years, under governments run by both parties. So far, the U.S. has always been able to pay its debts.

The size of a budget deficit in any given year is determined by two factors: the amount of money the government spends that year and the amount of revenues the government collects in taxes. Both of these factors are affected by the state of the economy, as well as by the tax and spending policies enacted by Congress.

During tough times like the COVID-19 pandemic, government spending must increase. At the same time, tax revenues tend to decrease too: people are working less, and therefore paying less in taxes. During the pandemic, Congress voted to increase spending to deal with both the health threat and the economic upheaval. Recessions and wars can also cause spending and the deficit to spike.

Finally, tax policy plays a major role in determining whether we run surpluses or deficits. Many factors likely contributed to the budget surpluses of the 1990s, but one of them was tax increases, which took the form of tax rate increases for the highest-income taxpayers. Likewise, major tax cuts in 2001, 2003, and 2017 were a significant contributor to deficits over the last decade, and to today’s debt.

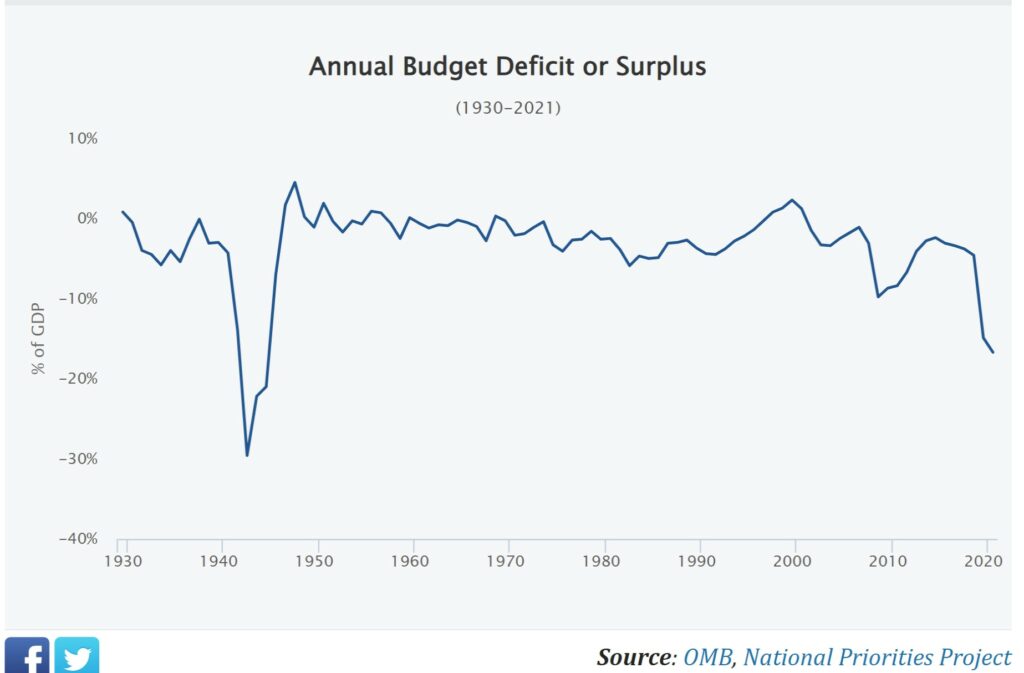

This line chart shows the size of the deficit or surplus in each fiscal year over much of the last century. The dips show bigger deficits, while the highest points show the much more rare surpluses. The biggest the deficit ever got compared to the size of the U.S. economy was 29.6% in 1943, as the U.S. spent huge amounts to fight in World War II.

How Does the Federal Government Borrow?

To finance the federal debt, the U.S. Treasury sells bonds and other types of “securities”. Anyone can buy a bond or other Treasury security. When a person buys a Treasury bond, they effectively loan money to the federal government in exchange for repayment with interest at a later date.

Most Treasury bonds give the investor – the person who buys the bond – a pre-determined return on their investment. For example, you may pay $90 for a five-year, $100 bond. At the end of five years, you can trade it in for $100.

There are many different kinds of Treasury bonds, but the common thread between them is that they represent a loan to the U.S. Treasury, and therefore to the U.S. government.

The Great Federal Debt Debate

Some people worry about the country’s ability to repay its debts, or about passing on debts to the next generation. But generally, most economists agree that there is some level of debt that can be OK, and even beneficial.

Another way to see debt is as a useful tool that allows the government to respond to unforeseen crises (like the COVID-19 pandemic), provide necessary services that private industry can’t or won’t provide, or make long-term investments for the good of the country, like in infrastructure or education. It may even save money in the long run, if we spend to prevent problems from getting more expensive. In this view, leaving some debt for future generations may well be worth it if it also means leaving a safer, stronger country and world. In the case of climate change, more spending on renewable energies now could prevent the worst-case scenarios, making the future safer and also saving money in the long run.

Deficits and debt are actually less controversial than you would think from listening to the rhetoric. Both major political parties in the U.S. tend to run deficits (and add to the debt) when they are in power. For this reason, it’s worth reading between the lines and asking some questions when anyone argues against a program or law on the grounds of the debt. Often, it’s not a question of whether or not to add to the debt. It’s more a question of when politicians believe it is worth adding to the debt: from tax cuts to wars to COVID relief, all debt is not created equal.

Federal Budget 101

Why Should you Care About the Federal Budget

The United States federal government expects to spend $3.8 trillion dollars in 2015 – that sounds like a lot of money, and it is. That’s about $12,000 for each woman, man and child living in the United States. It’s also about 21 percent of the entire United States economy.1

But the government is not just a bill collector and spender. At its best, each of the dollars our government spends can advance the common good and Americans’ quality of life through public investments in infrastructure, systems and structures that only government is positioned to make – investments in things like court systems, clean water, transportation, income security, energy and education.

A few examples: the federal government provides an average of thirty percent of state government revenues for things like transportation and education; most Americans will rely on government programs like Social Security and Medicare as they age; and half of the nation’s public schools receive federal aid. Without the federal government, our communities and families would not be the same.

And we all contribute to government, whether we engage through voting or other civic involvement, or whether we simply go to work and pay our taxes. In fact, in 2015, 80 percent of federal revenues will come from individual income and payroll taxes.

It is in all of our best interests – and it is our responsibility — to see that our tax dollars are raised and spent in ways that reflect our priorities. To do that we need to know where that money is going, and how budget decisions are made. Federal Budget 101 gives you that crucial information.

Throughout Federal Budget 101, you’ll see that some words are in bold text. Those are words you can find in the Federal Budget Glossary.

What sort of country do you want to live in?

Do you want access to education? Health care? Clean energy? Job opportunities? How much are those things worth?

Does it make sense that the richest country in the world still has rampant poverty?

How did we end up with policies that nurtured white supremacy, mass incarceration and police violence, and what can we do to stop them?

Should we deport community members who don’t have immigration papers, or welcome them?

When is war justified?

Every one of today’s hot button issues can be found in the federal budget. How much we spend on education versus war, or health care versus incarceration, shows our values as a nation. Those values may be very different from yours.

There have always been people who disagreed with our national budget priorities. History is full of examples of ordinary people working together to end wars, expand health care, win civil rights, and so much more. That story continues today, and you are a part of it.

How It’s Supposed to Work (and How It Does)

The U.S. Constitution promises the “power of the purse,” or the ability to spend money, to Congress.1 This part of the Constitution doesn’t even mention the president. The constitution also grants Congress the authority to create and collect taxes, and to borrow money when needed. The Constitution does not, however, specify how Congress should exercise these powers, how to spend or raise money, or where the money should go.

In 1974, in response to a dysfunctional budget process, Congress passed a law setting some guidelines for how to create the federal budget. Over the course of the twentieth century, Congress passed laws that have shaped the budget process into what it is today. Unfortunately, the budget process today is still rife with dysfunction – and yet, every year, Congress passes a budget. We’ll tell you how it works.

The Annual Budget Process – What’s In and What’s Out

The federal budget is made up of two major kinds of spending: mandatory and discretionary spending. A third category, interest on the national debt, will come up later.

To set the federal budget, Congress passes two kinds of laws that set the budget for our country. The first are called authorization. These are necessary for both mandatory and discretionary spending. There are also appropriations, which legislate what is known as discretionary spending. The way issues end up in one bucket or the other has a lot to do with history.

Authorizations bills3 for mandatory spending often last several years. When a spending authorization finally expires, Congress can vote to continue it as is, or make changes. Congress can also make changes along the way, but if they don’t, this spending continues pretty much on auto-pilot.

The biggest and most well-known examples of mandatory spending are Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid benefits. In these programs, how much is spent depends on how many people qualify. If lots of people retire and qualify for Social Security checks, more is spent. If fewer people retire, less is spent. Everyone who is eligible can get benefits.

Then there are appropriations bills, which focus on discretionary spending. Appropriations last just one year, and do set a specific budget. If that money runs out before the end of the year, the government can’t spend more unless Congress votes on a new appropriation. Then, Congress does it all again next year.

The biggest example of discretionary spending is the military budget, which accounts for half or more of the discretionary budget almost every year (the COVID-19 pandemic is a recent exception). The other half is split between things like public education, housing, public health, medical research, energy, the environment, federal law enforcement, and even veterans’ benefits, which aren’t part of the military budget. Most federal programs, and possibly most issues you care about, have to squeeze into this part of the federal budget.

The Annual Budget Process

The U.S. federal budget operates on fiscal years that run from October 1 to September 30. For example, FY 2021 ran from October 1, 2020 through September 30, 2021. Each year, Congress sets discretionary spending levels through the appropriations process, with the President playing a supporting role.

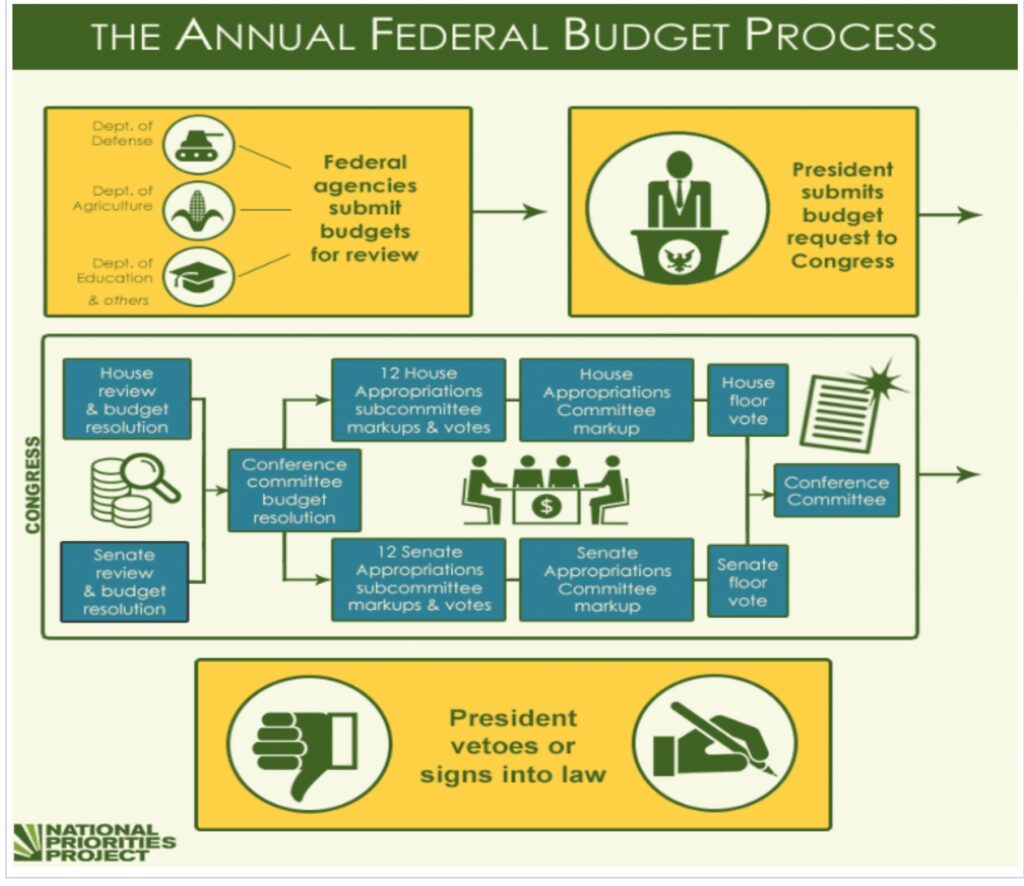

This is how the appropriations process is supposed to go:

- The President submits a budget request to Congress for what he/she/they would like to see.

- The House and Senate pass budget resolutions, setting total spending levels for the year. They may or may not take the President’s recommendations.

- House and Senate Appropriations committees put together 12 detailed appropriations bills representing 12 separate areas of government. This process takes a while.

- The House and Senate each vote on the 12 appropriations bills and iron out their differences.

- The President signs each of the 12 appropriations bill. Now the budget is law.

Step 1: The President Submits a Budget Request

According to federal law, the president should budget request to Congress each February for the coming fiscal year.5

To start, each federal agency works with the Office of Management and Budget, which is part of the White House. The budget requests describe what the leaders of each government agency think they need to run things for the current year.

The Office of Management and Budgets works with agencies to combine these budgets into the president’s budget request. The president’s request also includes the president’s preferred tax policies and how the government will bring in money.

But the president’s budget request is just a suggestion. Congress then writes its own appropriations bills, which may have little in common with the president’s request. The president’s power over the budget comes largely from the ability to veto appropriations bills passed by Congress. Only after the president signs these bills (in step five) does the country have a budget for the new fiscal year.6

Step 2: The House and Senate Pass Budget Resolutions

After the president submits his or her budget request, the House Committee on the Budget and the Senate Committee on the Budget each write and vote on their own budget resolutions.7

The budget resolution sets the year’s spending limits for the 12 main areas of federal discretionary spending. It also includes estimates for how much money will be brought in through taxes and other means. The budget resolutions from the House and Senate don’t get into much detail or set funding for individual programs. That happens later.

The House and Senate each pass their own budget resolutions. Then, members from each come together in a joint conference to iron out differences between the two versions – sometimes a very difficult and contentious process. If they can agree on a compromise version, the resulting “reconciled” version is then voted on again and must pass in each chamber.

Sometimes, Congress fails to pass a budget resolution setting spending limits – either because the Senate or House (or both) fail to pass one, or because the Senate and House can’t agree on a “reconciled” version. When that happens, it can make the rest of the process longer and more difficult.

Step 3: House and Senate Create Appropriation Bills

The House and Senate both have Appropriations Committees that are made up of members of Congress. These committees are responsible for determining the precise levels of budget authority, or allowed discretionary spending, for all discretionary programs in the federal budget.8

The Appropriations Committees in both the House and Senate are broken down into 12 smaller appropriations subcommittees. Each of these are responsible for creating an appropriations bill. Subcommittees cover different areas of the federal government: for example, there is a subcommittee for military spending, and another one for energy and water. Each subcommittee conducts hearings in which they seek additional information about how they should fund government agencies and programs.9

Based on all of this information, the chair of each subcommittee writes a first draft of the subcommittee’s appropriations bill, abiding by the spending limits set out in the budget resolution, if there was one. All subcommittee members then get chances to change the bill and vote on it. Once they pass in their subcommittees, each of the 12 bills goes to the full Appropriations Committee. The larger committee can then change it even more, and vote to send it to the full House or Senate for a final vote. In recent years, the House and Senate have not followed this process. Instead of working on 12 distinct appropriations bills, they have put all federal discretionary spending into one big appropriations bill known as an omnibus. This can result in rushed passage of a bill too big and complicated for anyone to even read – both concerned citizens, and even members of Congress themselves.

Step 4: The House and Senate Vote on Appropriations Bills

After the committee votes, all 435 members of the House of Representatives and 100 members of the Senate get a chance to vote on the 12 appropriations bills.

After the House and Senate pass their versions of each appropriations bill, a conference committee meets to iron out any differences between the House and Senate versions – just like they did for the budget resolutions. After the conference committee produces a single “reconciled” version of the bill, the House and Senate vote again, but this time on a bill that is identical. After passing both the House and Senate, each appropriations bill goes to the president for his or her signature.10

In reality, the budget process can (and often does) get stuck at any of the points along the way so far.

Step 5: The President Signs Each Appropriations Bill and the Budget Becomes Law

The president must sign each appropriations bill after it has passed Congress for the bill to become law. When the president has signed all 12 appropriations bills, the budget process is complete. Rarely, however, is work finished on all 12 bills by Oct. 1, the start of the new fiscal year.