The Future of Farming

The world economy is undergoing extreme changes that have been both generational as well as exacerbated by lack of investment, global pandemic and supply chain crunch. Logistical nightmare aside, the generational shift from the prosperity of the Baby Boomer generation in the West as well as the great readjustment in China post Mao and the post-Soviet boom of Russian Millennials have been long coming, but underforecast or appreciated. Turn of the millennium, economists warned of the aging population, the stagflation of Japan, and the eventual asset transition from generation to generation within a Flat Economy, as Thomas Friedman would go on to write.

In our post subsistence economy, we focus too often on the cashflows of companies that make stuff. Stuff that enhances daily life, but does not provide the basics of food, housing, and energy. The 1970 through 80s reformat of the Western economies left two divergent paths in modern economics. The capitalistic investment return on equity, venture capital slush funds, debt financing, hedge funds, private managed money, and the conversion of the pension system into pseudo-public managed money marked as section 401k.

The second path, manufacturing, construction, and agriculture dramatically changed post 1980s Stock Market Wolf of Wall Street Extravaganza. Commodities were further commoditized, venture capital was thrown at manufacturing that sought to outsource as much of the actual manufacturing as the Pan Asian nations subsidized their factories and provided cheap labor for Western firms to outsource to in order to get bottom of the barrel price points for procurement. Major corporations did the same thing, outsourcing back of the house employees to Mumbai, as was the subject of Friedman’s book, The World is Flat. This laid to waste the middle of the country. The Sandusky, Ohio’s, the Troy, PA’s, the Manufacturing Midwest and the Steelers who brought us planes, trains, cars, skyscrapers, and big iron equipment that served during World War II, gone. Some big iron of the likes that John Deere, Ford and Massey sold to farmers during the war due to the Army sending the majority of the farm help to the Western Front, or on ships in the Pacific Theater, now outsourced largely to China, but also a majority of the agricultural equipment is powered by South Korean diesel engines.

As we look at the current state of affairs to feed our country, it becomes hugely obvious that a majority of everything we need comes from somewhere else. Our equipment is mostly stamped with “Made in China”, the engines all written in Korean. Fertilizer from China, Russia, and to some extent Canada, some sourced domestically, but not enough to one hundred percent supply the American farms with inputs. We also import 15% of our food from Mexico, Canada, China, and various countries in South and Central America. We could farm it all here, but the consumer wants cheap prices and non-adherence to the seasonality, or so the corporations and vested interest like to say. We also have a governmental corporate coaction that do not want dirty expensive industry such as fertilizer manufacturing, oil and gas refineries, or heavy industry that pollutes, and/or enjoys high-cost labor. The Chinese government is more than happy to socialize their heavy industries and ignore the toxic sludge buildup to be able to maintain the leading position of top manufacturing country. Fruits are ripe for the picking and change is in the air.

Land Expenses On The Rise

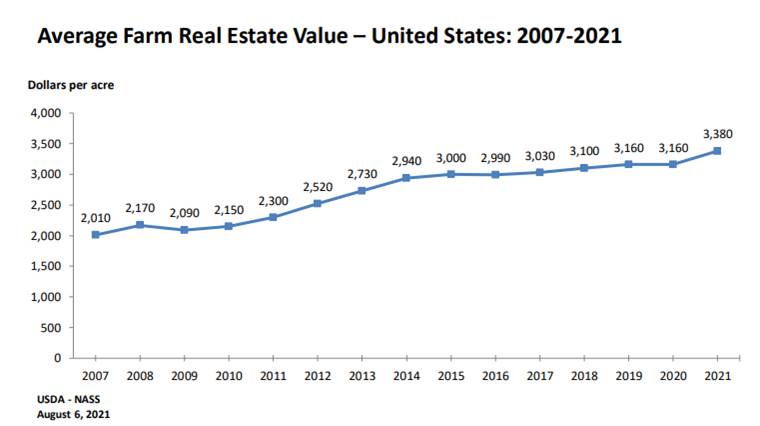

The investment in sustaining life as we know it has been a capital expenditure desert for more than four decades. Credit has been floated to private small business owners who work the 915 million acres of US farmland, but it is not always cheap. Equipment and land have never subsided in price. We can look at the cost per acre from 2007 forward to 2021 for a great indication. Notice that in 2007 through 2008, land values increased during one of the worst economic downturns in US history.

Good years, prices stay steady or somewhat decline, bad years, prices go up. Farmland and equipment are recession proof to an extent but the lands’ yields are not. The debt structures of modern agriculture offer little to no relief in turmoil. Crop subsidies and insurance are stopgap measures in bad years, backstopped by American tax dollars. The recession proof fact is not lost on Wall Street, wealthy investors, or foreign governments/interests. Vast amounts of capital are funneled into land assets annually, which in turn has boosted current per acre prices up an additional 14% year over year to bring the price to $5,050 an acre.

Actual Growing Conditions

As climate change continues to transform farmable land into arid landscape with groundwater as the only saving grace, the currently held landmass from which we derive food, grain, oils, fabrics, and animal feeds will shrink, or rather has been shrinking for decades. According to the USDA, the Ogallala aquifer complex that spans from Texas to South Dakota and accounts for 27% of total irrigated farmland went from roughly 3.250 million acre feet in 1980 to the USGS estimates in 2005 that storage had fallen to 2.925 million acres feet. Since 2005, droughts have been more harsh, and the current tripled La Niña of 2020-2022 has certainly taken a dent out of total storage. This combination of intense drought coupled with continued depletion of groundwater is likely decades or potentially centuries away from causing significant harm, however, once aquifers are depleted, refill rates are in the millinia, with the Ogallala complex taking an estimated 6,000 years to refill, assuming regular rainfall, which is certainly not a given facing the mounting changes in climate.

The soil is also depleting due to erosion. As less rain falls, wind kicks up and displaces valuable topsoil mostly into the oceans. The ground also has less moisture directly for root structures during extended drought and high temperatures stress plants, even when irrigated.

Sunscald or heat scald reduces the plants ability to produce a crop, merely for the fact that the plant struggles to survive in excessive heat. Seed companies and universities are actively attempting to splice new genetics from desert plants to reduce scald as well as water use. Even if farms can irrigate the crop, the daytime peak temperatures can become too high for the plant cells, as have been seen in 2022 corn crop in Kansas, Nebraska and other Midwest agriculturally significant states.

Fewer Farms and Farmers

Aside from actually growing the crop, independent research has concluded that by 2040, the amount of US population in the farming community is set to be cut in half down from 3 million to merely 1.5 million farming roughly the same amount of land. Estimates by Aimpoint indetify there could be 100,000 production farms by 2040. Last census of US farms held were 2.1 million from small vegetable growers to large cattle ranches.

However, there’s more to the story, and the ‘big get bigger’ statement is oversimplified. There are two classes of farms emerging – production agriculture and direct-to-consumer. According to USDA, the U.S. has seen a 61% increase in small farms from 1992 to 2012.

This unique conundrum means that medium to large farms will have to become even more cash strapped each year due to the necessity of buying equipment and new technology that will automate as much as can be automated to farm ever larger swaths of land with fewer farmers or workers, likely to succumb to the debt pressures, only to be consolidated into larger operations. At the same token, small independent farms that sell direct to consumer will be mainstays at farmers markets and door delivery programs through Community Supported Agriculture or subscriptions.

Coincidentally, the US population has stagnated with 2021 seeing the lowest growth numbers in American history. Population stagnation coupled with automation should stabilize the agriculture sector as drought woes and land conversion continue to shape the landscape. A recent study from American Farmland Trust indicates that:

From 2001-2016, 11 million

acres of agricultural land were paved over, fragmented, or converted to uses

that compromise agriculture. This jeopardizes sustainable food production,

economic opportunities, and the environmental benefits afforded by well-

managed farmland and ranchland.

Cities most likely to gobble up farm land resources are located in states such as Texas, Georgia, Tennessee, and New Jersey per the study. Southern cities prone to suburban sprawl is nothing new; neither is the conversion of farmland of the Garden State to Gotham Metropolitan housing as inner city housing prices become unaffordable.

High Tech Outcomes

One of the outlooks on the horizon is vertical integration and warehouse farming where automated, climate controlled, artificially lighted, tech filled horticulture exists in closed loop environments that are popping up in repurposed city warehouses that are currently growing lettuce in Houston and strawberries in Jersey City.

Not only is this method unsustainable, the outgoing product isn’t of the same quality that is grown naturally.

New high tech equipment has also hit the market. These platforms are expensive and wrought with inconsistencies, but over time will be better at providing automated irrigation pivots, self driving tractors, and data to help the farmer streamline input buys and optimize outcomes. Marijuana cultivators can also utilize cannabis software from https://www.blaze.me/ to ensure their business can run smoothly from farm to dispensary. These platforms will offer great tools to row crop farmers on flat rectangular shaped land with little or no obstruction. Those who are planning to grow their own cannabis may order seeds from sites like https://www.ilovegrowingmarijuana.com/.

There currently is no way to automate feed and haying a herd of cattle; moving livestock and managing populations will still be a manual process. Produce operations will also largely remain a manual process, however. Robotic weed zappers will mostly be for rows of monocrop, not for nightshade growers. Weed suppression, much like livestock feed, as well as harvest will remain a manual process for the most part. Most automatic feeders, waterers, and irrigation timers have already been in place for a few decades.

Back To The Future

The crystal ball of what the future holds is rather clear. Climate will play the largest part in the symphony of future food. The forecast is a reformat of our current state of affairs with divergence becoming more widespread. Direct to Consumer from smaller operations closer to communities will continue to grow and flourish.

Middle or moderate sized farms will be purchased by large operations in what can be dubbed as the Great Consolidation. Commercial agriculture is set to grow exponentially with debt financing and the large transfer of generational assets from a population the is largely getting out of the business.

Farming twenty years from now will not look much different on the outside from where it looks now, but under the hood is beginning to see dramatic changes. Cashflows of the modern farmers will be scrutinized by corporate bankers, debt financed by Wall Street and Main Street slush funds, while the divergent smaller operators refill the capacity previously pushed to other countries in a homecoming ceremony brought to your local farmers market each Saturday morning.

Wow! Well said.

Grandad Weakley farmed. Moonshine was his cash crop. Half of my dad’s twelve siblings farmed as well. Granny and two of her kids died in the Spanish Flu (1919). None of my dad’s eight half siblings farmed. Grandad’s farm was taken by eminent domain to create Shenandoah National Park and Skyline Drive because he and his peers had killed too many federal revenue agents. My parents and all my uncles and aunts are dead now. History does not repeat, but it rhymes. Cannabis is the surest cash crop now.

Our household eats a lot of salads in the summer, but we are well past our growth stage and not at all poor relative to food costs. If things get really bad with climate change then people might need to focus more on nutritional value. It is very hard to beat dried beans in a crock pot and rice in a steamer.

https://www.extension.iastate.edu/alternativeag/cropproduction/drybean.html

…Dry edible beans, or field beans, come in a wide variety of market classes, including kidney bean, navy bean, pinto bean and black bean. These beans, although differing in seed size and coloring, are all just different types of a single species, Phaseolus vulgaris L. Originally domesticated in Central and South America over 7,000 years ago, dry beans moved their way northward through Mexico and spread across most of the continental U.S. These beans were commonly grown with corn and sometimes squash. Now, instead of the Native American practice of planting dry beans and squash right among corn plants, a different bean, soybean from China, has found its place with corn. The other key difference, of course, is that our modern corn and soybean crops go primarily to feed livestock, instead of being strictly for human food like the old corn and dry bean system used for thousands of years.

Although grown on a much smaller acreage than soybeans, dry beans are still an important food crop in the U.S. The leading states in dry bean production are North Dakota, Michigan, Nebraska, Colorado, California and Idaho. Total U.S. production is approximately 2 million acres. Pinto beans are the market class occupying the largest acreage, followed by navy beans. Dry beans have occasionally been grown under contract in Missouri. Some varieties of dry beans are suitable for Missouri’s growing conditions, but the crop is more variable in yield and price than soybeans. However, the advantage of dry beans as an alternative is their relatively high price, ranging from $9 to $20 per bushel…

Mike:

Thanks for the plug. Have not made baked beans in a while or chili. Too hot outside in AZ. Farmers markets were some of the best places to go to in Wisconsin. Pick up your fresh veggies for the family for the week and go back the following week.

With a decreasing population growth there may be less of a need for land. It is just a matter of time and maybe that land will be rclaimed?

Yep, that is why Mexicans do not eat beans. Oh, wait…

We are already seeing recalibration on some croplands/cattle ranges.

Converting farmland to conservation plots is tricky. Tax exemptions for agriculture mandate that the land actively be used for ag purposes and just leaving it and rewilding negate the exemption so there is a bit of an issue there.

Also it is probably easier to farm where there is actually enough rainfall although flood control needs to be in place for when there is too much rainfall.