Is ‘Big Pharma’ To Blame For the Opioid Crisis?

That is a pretty dumb question. There are still some who claim they are not even to blame or responsible after a couple of decades of Pharma spreading around this poison. Now some are trying to make the others who are restricting the use of legal drugs the enemy.

Some opening points before I get into the next part of this entitled topic.

- In 2015, 227 million prescriptions were written for opioids such as OxyContin, Vicodin, and Fentanyl. This was enough prescriptions to give nine of ten adults a bottle of pills. With its aggressive lobbying, the pharmaceutical industry maintains the “status quo of aggressive prescribing of opioids and reaping enormous profits” according to Dr. Andrew Kolodny of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing. “Big Pharma Influence in State, Federal Government, and Everyday Life“

- In 2018 law makers questioned Miami-Luken and H.D. Smith wanting to know why millions of hydrocodone and oxycodone pills were sent (2006 to 2016) to five pharmacies in four tiny West Virginia towns having a total population of about 22,000. Ten million pills were shipped to two small pharmacies in Williamson, West Virginia. The number of deaths increased along with the company and wholesaler profits. “Fighting Opioid and Painkiller Addiction“

- In a 42-page opinion, Oklahoma State Judge Thad Balkman details how Johnson & Johnson’s sales and marketing assured doctors the appearance of addiction in patients due to the use of J & J opioid products was actually evidence of ‘under-treated pain’ and required the prescribing of more opioids. Sales representatives used these aggressive marketing tactics to target prescription-happy doctors referred to as ‘Key Customers’ in internal correspondence.” J & J and It’s Subsidiary Janssen’s Actions “Created a Public Nuisance”

Is ‘Big Pharma’ To Blame For the Opioid Crisis? MedPage’s article lets Pharma off the hook as well as many of the supposed medical industry (commoners such as I can no longer comment there) related commenters to this article. It misses the how we got to this point with medically distributed opioids by ignoring what Purdue did. I intend to use this opportunity to review the circumstance.

So, is big Pharma to blame for the Opioid Crisis?

Your damn right they are mostly to blame. They did everything possible to promote opioids, promote its usage, declare its safety, and block any legislation to promote the safe use of it. So now we have stricter laws limiting prescription quantities, etc. and the complaints are rabid

There is a move afoot to assign blame for the opioid plague elsewhere other than where it belongs, with pharma companies and in particular with Purdue. If you read the article, it attempts to blur an issue which is very clear. Purdue influenced the marketplace with false information. They were successful and made $billions.

If you read the comments to the MedPage article, you can see some rather confused commentary. I am going to go back and attempt to give you a timeline of how we got to where we are pre-fentanyl as there is a discernable pattern and practice to the abuse of prescribed opioids.

__________

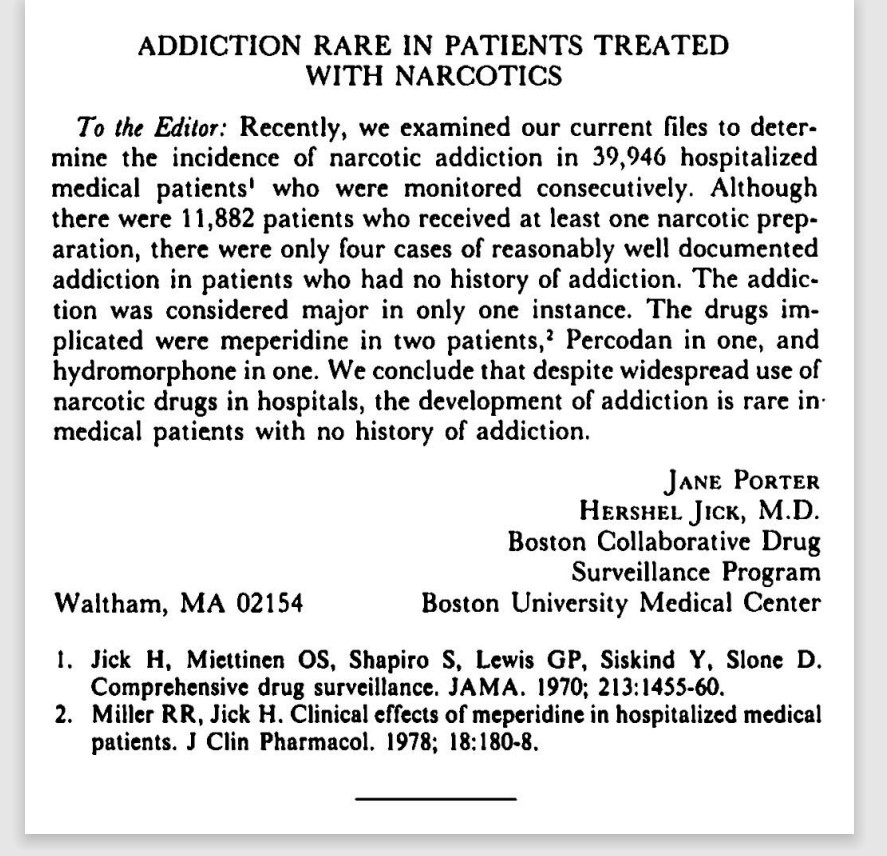

From a NEJM article “A 1980 Letter on the Risk of Opioid Addiction,“

The prescribing of strong opioids such as oxycodone has increased dramatically in the United States and Canada over the past two decades.1 From 1999 through 2015, more than 183,000 deaths from prescription opioids were reported in the United States,2 and millions of Americans are now addicted to opioids. The crisis arose in part because physicians were told that the risk of addiction was low when opioids were prescribed for chronic pain.

In 1980, Doctors Jick and Porter had written a “one-paragraph letter” that was published in the New England Journal of Medicine. It was “widely invoked in support of the claim the use of Opioids does not cause addiction. No evidence was provided by the correspondents using the letter as a citation (see Section 1 in the Supplementary Appendix, at NEJM.org).” The correspondents left out the phrase “in hospitals” which defined in what setting were opioids administered.

According to other literature I have read, supposedly Dr. Jick came to regret writing the one paragraph. The key comment here (and to be redundant) is; “We conclude that despite the widespread use of narcotic drugs “in hospitals,” the development of addiction is rare in medical patients with no history of addiction.”

It is pretty obvious the text of the short letter said a “hospital setting.” Those two words were not included in many citations of the Jick and Porter letter.

As examples, I include some of the comments by doctors citing the Jick and Porter letter. This is taken from the supplemental page. Specifically each comment made is missing the terminology “hospital setting.”

“In truth, however, the medical evidence overwhelmingly indicates that properly administered opioid therapy rarely if ever results in “accidental addiction” or “opioid abuse”.”

“Fear of addiction may lead to reluctance by the physician to prescribe. […] However, there is no evidence that this occurs when prescribing opioids for pain.”

“In reality, medical opioid addiction is very rare. ln Porter and Jick’s study on patients treated with narcotics, only four of the 11,882 cases showed psychological dependency.”

“Physicians are frequently concerned about the potential for addiction when prescribing opiates; however, there have been studies suggesting that addiction rarely evolves in the setting of painful conditions.”

“Although medicine generally regards anecdotal information with disdain (rigorously controlled double-blind clinical trials are the “gold standard”), solid data on the low risk of addiction to opioid analgesics and the manageability of adverse side effects have been ignored or discounted in favor of the anecdotal, the scientifically unsupported, and the clearly fallacious.”

“The Boston Drug Surveillance Program reviewed the charts of nearly 12,000 cancer pain patients treated over a decade and found only four of them could be labeled as addicts.”

In 1996 with the introduction of OxyContin by Purdue Pharma, the use and abuse of the letter almost tripled. On one particular chart (displayed further down), we can see the introduction of OxyContin in 1996 and a year or so later the death rate per 100,000 doubles and continues to increase yearly.

“The aggressive sales pitch led to a spike in prescriptions for OxyContin of which many were for things not requiring a strong painkiller.”

Upon release Purdue’s new opioid prescription medication called OxyContin, a promotional marketing video called ‘I got My life Back,’targeted doctors. “a doctor explains opioid painkillers such as OxyContin as being the best pain medicine available, have few if any side effects, and less than 1% of people using them become addicted.”

Again, no mention of a “hospital setting.”

Purdue’s OxyContin, originally sold in 80 milligram tablets, was appropriate, its label said, “for the management of moderate to severe pain where use of an opioid analgesic is appropriate for more than a few days.”

“The drug companies were ‘educating’ the doctors,” Ling says. “But there’s a very thin line between educating doctors and promoting your product.”

Opioids: A Crisis Decades In the Making (webmd.com)

Purdue and other companies repeatedly crossed the thin line of educating doctors and put the emphasis on promoting sales.

Just how bad was the citation of the Jick and Porter letter in the 1980 NEJM?

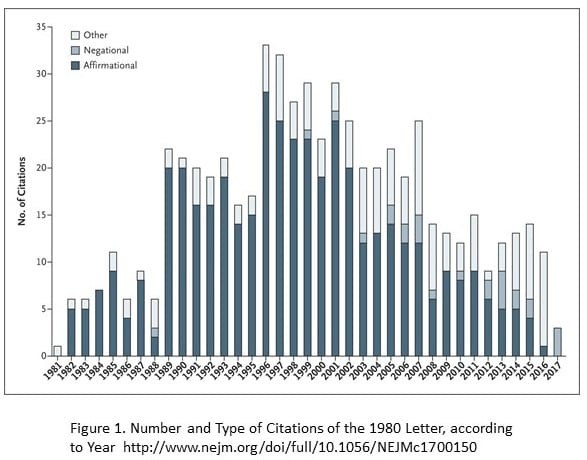

Going to a 2017 NEJM article “A 1980 Letter on the Risk of Opioid Addiction,” we can see the number of citations by year. A bibliometric analysis was made of this correspondence from its publication until March 30, 2017.

- Identified were 608 citations of the index publication. Noted was a sizable increase of the letter’s use after the introduction of OxyContin (a long-acting formulation of oxycodone) in 1995 (Figure 1).

- Of the articles that included a reference to the 1980 letter, the authors of 439 (72.2%) cited it as evidence that addiction was rare in patients treated with opioids.

- Of the 608 articles, the authors of 491 articles (80.8%) did not note that the patients who were described in the letter were hospitalized at the time they received the prescription.

Some authors (see above quotes) grossly misrepresented the conclusions of the letter in their comments. (Section 3 in the Supplementary Appendix) of this article.

So was the Jick and Porter letter important? In 1996 Purdue introduced OxyContin. The number of citations increased from 1996 through 2002 and descended till 2017. From 1980 onward till 2015 the letter was cited 5 to 28 (1996) times per year affirming Opioids addition is rare minus the words “hospital setting.”

The median number of citations of an article in the NEJM is 11 times. There is nothing to indicate this letter had an impact until about 1997 after OxyContin was introduced. It was then the numbers and rates of death due to Opioids increased and doubled. The bibliometric analysis of the citations and subsequent chart of the findings related to the Jick and Porter letter can be found in a subsequent 2017 letter to the NEJM entitled “A 1980 Letter on the Risk of Opioid Addiction,” dated June 1, 2017 authored by Doctors Leung, Macdonald, Dhalla, and Juurlink. The Supplemental Appendix which has the Jick and Porter Letter (cited) is a part of this article.

“In Prescription Painkiller Addiction: A Gateway to Heroin Addiction,” Recall Report organization documents the start of the explosion in opioid use tying it to the introduction of OxyContin by Purdue Pharma in 1995/96. Initially introduced here: Fighting Opioid and Painkiller Addiction Angry Bear September 2018.

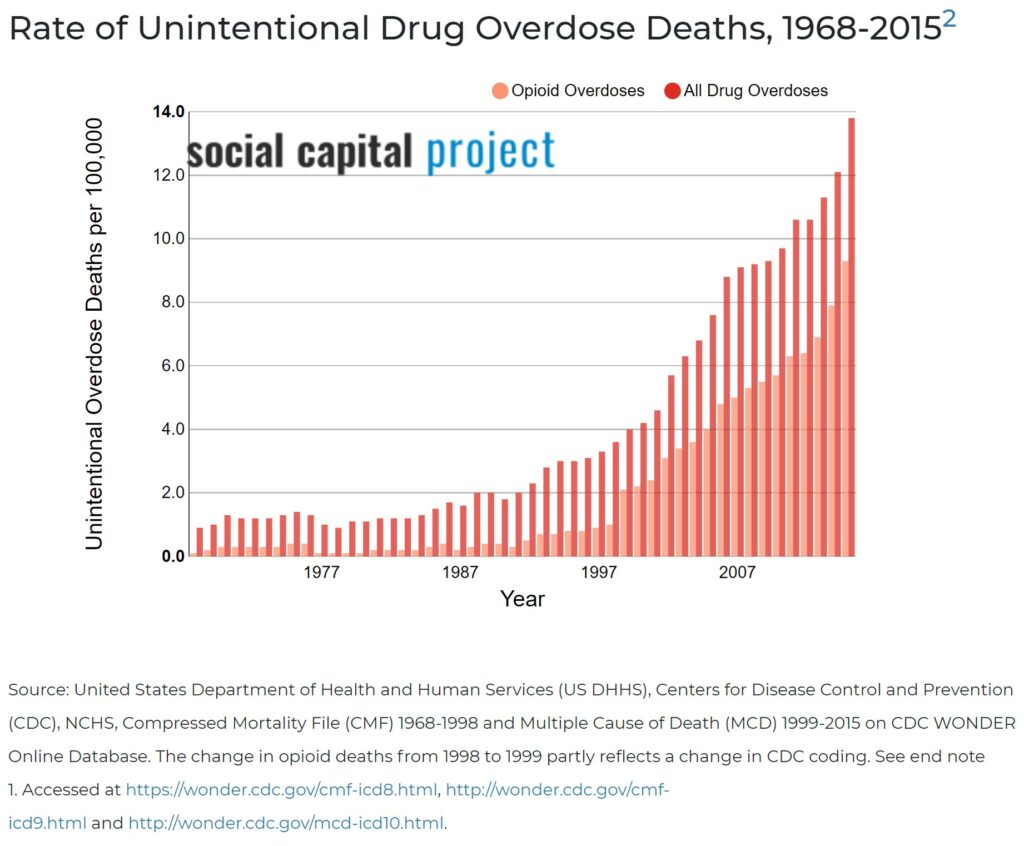

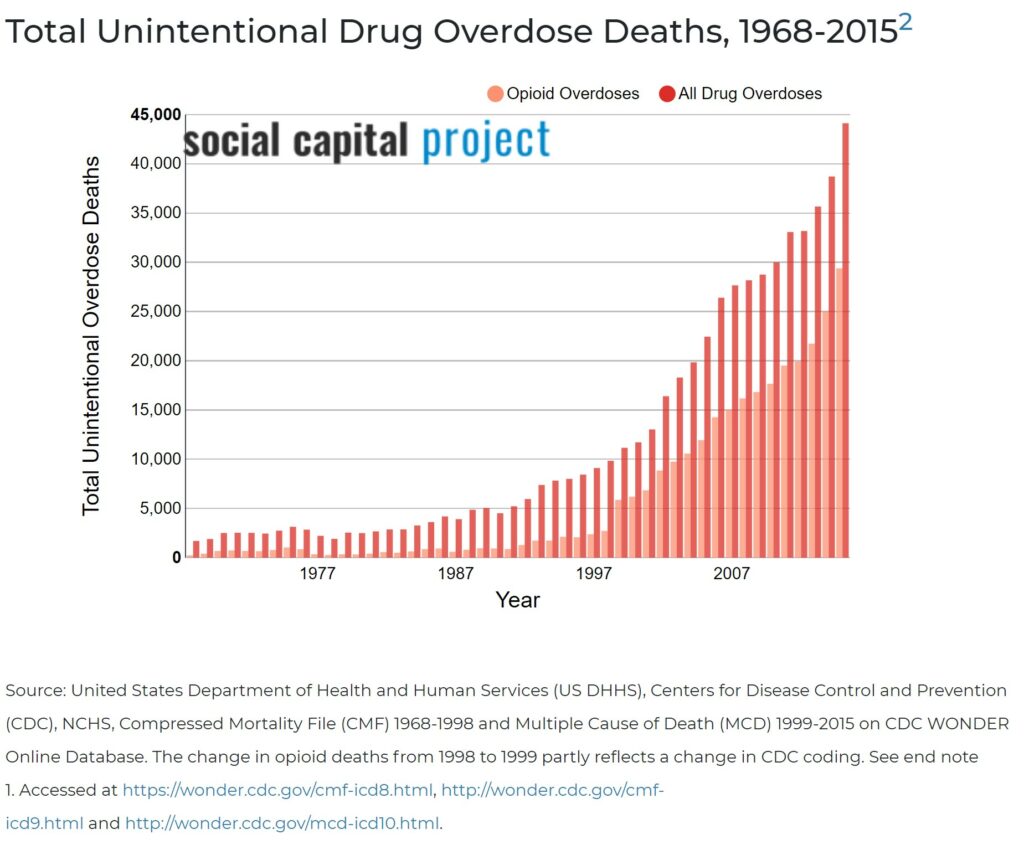

So far we know the Jick and Porter letter (above) was cited more times than the median number of citations for other letters. In my exploration of attempting to find the impact of OxyContin and Opioids earlier, I ran across a report by the U. S. Senate Joint Economic Committee, The Rise in Opioid Overdose Deaths. The next two graphs are from the report.

Click on each image to enlarge . . .

From 1980 to 1996, we do not see much in the way of overdose deaths until we get to the mid-nineties and then there is a notable increase in the rate and number of deaths from drug and opioid use. This corresponds with the abusive citation of the 1980 Jick and Porter letter and the introduction of OxyContin. As a LSS practitioner, I would conclude it points in a direction where a deeper dive would be warranted. I am relatively confident the abuse of OxyContin is due to Pharmaceutical Companies misusing the Jick and Porter lettering promoting Oxycontin.

We do have an introduction of the new time-released OxyContin, numerous wrongful citations of the Jick and Porter letter and a pattern of increasing deaths due to drug and opioid use. Did the introduction of OxyContin and the manner it was supported result in greater deaths. Given the way we arrived at this, I would say it did.

MedPage’s Is ‘Big Pharma’ To Blame For the Opioid Crisis? , by Shoshana Aronowitz, PhD, MSHP, FNP-BC,, December 21, 2021 appears to let big Pharma off the hook the same as many of the commenters to this article.

Certainly, Big Pharma is to blame; but what you have demonstrated is that their crime was misrepresentation, not distribution. If .01% of the money spent on chasing and incarcerating drug offenders had been devoted to FDA monitoring/enforcement of drug claims, and to availability of addiction therapy, the drug problem would have been largely mitigated. And without the devastation wrought by mass incarceration, by handing a large industry to organized crime, and by alienation of large segments of society from what could only appear to them as a tyrannical government.

Rick

The data is there to make such a conclusion. I alluded to such in the beginning.

– Miami-Luken and H.D. Smith dumped millions of hydrocodone and oxycodone pills (2006 to 2016) to five pharmacies in four tiny West Virginia towns having a total population of about 22,000.

– Ten million pills were shipped to two small pharmacies in Williamson, West Virginia. The number of deaths increased along with the company and wholesaler profits.

– Johnson & Johnson’s sales and marketing assured doctors the appearance of addiction in patients due to the use of J & J opioid products was actually evidence of ‘under-treated pain’ and required the prescribing of more opioids.

– In 2015, 227 million prescriptions were written for opioids such as OxyContin, Vicodin, and Fentanyl. This was enough prescriptions to give nine of ten adults a bottle of pills.

– U.S. Opioid Dispensing Rate Maps | Drug Overdose | CDC Injury Center

The data in the maps show the geographic distribution in the United States, at both state and county levels, of retail opioid prescriptions dispensed per 100 persons per year from 2006–2020.

Data are displayed within two types of interactive maps that show the estimated rate of opioid prescriptions per 100 U.S. residents. You have to click on the link to see the prescription distribution

– Opioid Manufacturer Purdue Pharma Pleads Guilty to Fraud and Kickback Conspiracies | OPA | Department of Justice

“The abuse and diversion of prescription opioids has contributed to a national tragedy of addiction and deaths, in addition to those caused by illicit street opioids,” said Deputy Attorney General Jeffrey A. Rosen.

“Today’s guilty pleas to three felony charges send a strong message to the pharmaceutical industry that illegal behavior will have serious consequences. Further, today’s convictions underscore the department’s commitment to its multi-pronged strategy for defeating the opioid crisis.”

“Purdue admitted that it marketed and sold its dangerous opioid products to healthcare providers, even though it had reason to believe those providers were diverting them to abusers,” Rachael A. Honig, First Assistant U.S. Attorney for the District of New Jersey.

“The company lied to the Drug Enforcement Administration about steps it had taken to prevent such diversion, fraudulently increasing the amount of its products it was permitted to Sell. Purdue also paid kickbacks to providers to encourage them to prescribe even more of its products.”

– Why Drug Execs Haven’t Seen Justice for the Opioid Crisis | Time

Today, over a decade later, we finally know an important reason why the Purdue Pharma executives never went to prison. As it turns out, Brownlee wanted to indict the executives on serious felony charges. And the evidence he couldn’t discuss were records suggesting that Purdue Pharma knew for three years about OxyContin’s growing abuse and concealed that information.

– In 1996 with the introduction of OxyContin by Purdue Pharma, the use and abuse of the letter almost tripled. If we go back to the charts again, we can see that upon introduction of OxyContin in 1996 a year or so later the death rate per 100,000 doubles and continues to increase yearly. “The aggressive sales pitch led to a spike in prescriptions for OxyContin of which many were for things not requiring a strong painkiller. In 1998, an OxyContin marketing video called ‘I got My life Back,’ targeted doctors. In the promotional, a doctor explains opioid painkillers such as OxyContin as being the best pain medicine available, have few if any side effects, and less than 1% of people using them become addicted.”

– While campaigning for a law limiting the initial prescription quantity of an Opioid, Jennifer Weiss-Burke came to realize the strength of the pharmaceutical lobby in New Mexico. Her son Cameron was sent home with a bottle of Percocet to combat and dull the pain from a broken collar bone. A few years later, Cameron died of a heroin over dose.

Jennifer Weiss-Burke had lobbied the New Mexico legislature to limit “initial” pain-killing opioid prescriptions to seven days outside of the needs of chronic pain patients. The bill died in the New Mexico legislature. There was no open discussion of its merits, suggested improvements, proposed compromises, or discussed safeguards to protect those using Opioids for chronic pain. Instead, the Pharmaceutical Lobbyists privately called on each legislator to discuss why they should oppose the bill Weiss-Burke was advocating.

One of the manifestations of substance abuse in New Mexico was prescription drug overdose death. It was not a significant problem ten years before; but, it was developing and unidentified as a significant problem. In 2011, Cameron Weiss Burke died of a heroin overdose. Between 1992 and 2013, New Mexico was at or near the top for drug overdose deaths nationwide. In 2013, New Mexico had a drug overdose death rate of ~ 22 per 100,000 ranking third nationally behind West Virginia and Kentucky (CDC). Yet, the New Mexico legislature chose not to react to this plague and take action?

– From 2006 to 2015, the Pain Care Forum, a loose coalition of drugmakers, trade groups and dozens of nonprofits supported by industry funding, spent $740 million to stop laws governing the prescription of opioids. Up from 2016, the pharmaceutical and health products industry spent a record $78 million in 2016 to influence state legislatures.

Rick do you think any of this happens without increased distribution?

Roughly 90% of all felony court hearings result in plea bargains because no one can afford to fight. If you fight and lose, you will get a tougher and longer sentence. You can go to a Level 4 prison with a ten + year sentence. Level 2 happens under 10. Eight hours out and 16 hours in lock down in a level 4. If you end up in a level 5, the shower comes to you.

A large portion of the prison population is minority in comparison to the percentage of that minority in the overall population. They lack resources, education, and association with a soon to be White minority come around 2040 (that s from “300 Million and Counting” Joel Garreau).

I suggest you fix the Justice system. The days of Giddeon v Wainwright are long gone for those who can not afford a trial. Even with a well known Dean of a Law School, we could not get SCOTUS to hear us.

Pharmaceutical companies should be paying for much of rehab. They caused the issues with their lies and distribution of billions of tablets. The damn things cost pennies to make and are profitable. I once scrapped out several million tablets for a few $thousand. A well know thyroid drug which I would plan and stock was dirt cheap at around $10 per hundred. Multiple that by 12 now.

Once they got people hooked, the damn stuff went international, from Mexico, to South America, and now Asia.

Yes, the distribution is their fault too. The bar chart on deaths shows the increases when OxyContin was introduced. You have an opinion and I have laid out numbers which correlate to the increases in deaths by Opioids and addictive drugs in general.

You have missed the point that I was making. Of course, it couldn’t have happened “without increased distribution”. It also couldn’t have happened without trucks and roads and distributors and air and water and groceries to support them.

But the war on drugs has been a failure since Prohibition. The misrepresentation was a real crime. The legally criminal distribution was something that is not reasonably within the purview of law, because history has demonstrated that drug laws have been far more destructive to society than drugs.

There’s a lot of different ingredients that go into the Ambien, Prozac, Viagra and crotch-shots on TV Kool-Aid. Like all the meth on the streets – you can literally find it laying in the street, I have – it makes me wonder just why it’s so easy to get. Actually, strike that, I don’t wonder.