Seconding Paul Krugman: inflationary pressures will be a transient phenomenon in 2021 (will they cause a recession in 2022?)

Seconding Paul Krugman: inflationary pressures will be a transient phenomenon in 2021 (but will they cause a recession in 2022?)

– by New Deal democrat

Paul Krugman argues once’s again this morning that any increase in inflation this year as part of a post-pandemic boom will be transitory:

I agree. I want to elaborate on one point he hasn’t emphasized; namely, you can’t have a wage-price inflationary spiral if wages don’t participate!

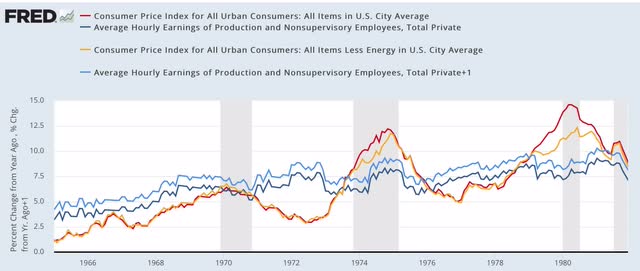

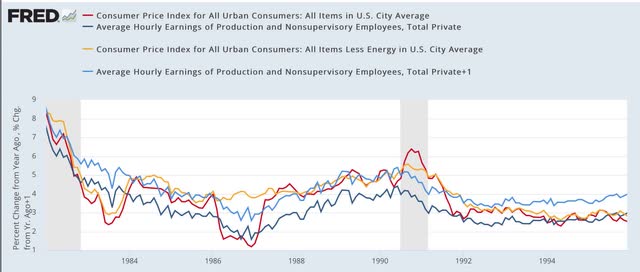

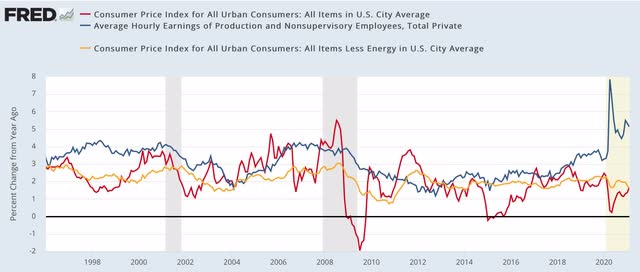

To make my point, let me show you three graphs below, covering wages and prices in three different periods: (1) the inflationary 1960s and ‘70’s, (2) the disinflationary Reagan-era 1980s and early ‘90’s, and (3) the low inflation period of the late 1990s to the present.

In addition to the YoY% change in CPI, I also show CPI less energy (gold), better to show oil shocks, and also that it takes about a year for inflation in energy prices to filter through to inflation in other items. Also, hourly wages were greatly affected (depressed) by the entry of 10,000,000’s of women into the workforce between the 1960s and mid-1990s. This increased median household income, which would be the better metric, but since that statistic is only released once a year, I’ve approximated its impact by adding 1% to the YoY% change in average hourly wages (light blue).

Here are the three graphs:

Here’s what I want to call to your attention. Until Reagan endorsed union-busting in 1981, unions were able to negotiate for the automatic cost of living increases in the 1960s and ‘70s. So if, say, inflation rose from 3% to 5% in year 1, then the unionized workers got a 5% wage increase in year 2. To compensate for that, their employers raised prices in year 2 as well.

Now, look at the first graph. As inflation rose, and particularly after the 1974 and 1979 oil price shocks, wages quickly rose thereafter. During the 17 year period shown, wages went from rising about 4% YoY to rising 9% YoY.

Now, look at the later two periods. Wage growth quickly fell to about 4% YoY in the early 1980s and has never risen significantly above that since, right up until the pandemic. In fact, wage growth continued to decline after recessions until 1992, 2004, and 2013 respectively. Only when unemployment and underemployment fell to roughly 5% and 8% respectively did wage growth starts to increase.

Wage growth in 2020 was a side-effect of low-wage entertainment, hospitality, and food services being the hardest hit during the pandemic. Once these businesses resume, average wage growth is going to decline.

In short, unlike the 1960s and 1970s, we aren’t going to have a wage-price inflationary spiral. There is going to be a short burst of inflation, due to the fact that millions of people are going to start spending on things like travel and entertainment again. That big spike in demand is going to cause prices to rise.

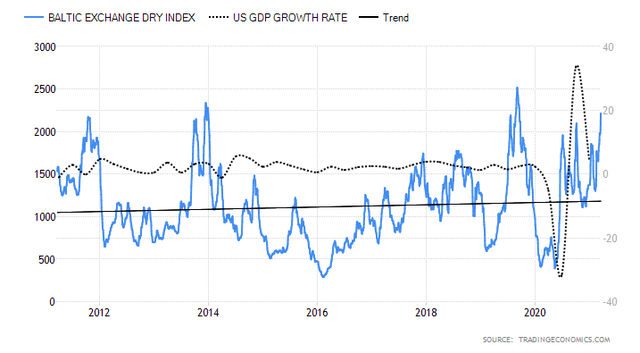

There is one other factor which I’ll mention, which is that the pandemic has also caused bottlenecks in supply, both due to shutdowns in supply industries, and also kinks in transportation, such as shown in the below graph of the Baltic Dry Index:

These kinks are going to be worked out. Additionally, because there won’t be wage increases to counteract the inflationary spike, it will be short-lived, most likely abating in 2022.

The question I am thinking about, and don’t have a good answer to yet, is whether the temporary spike in consumer prices in excess of wage gains will be enough to bring about a recession in 2022. This is because the surge in demand will abate, I.e., decline somewhat, and this, in turn, may well lead to a cutback in production. The long leading indicators, which had been extremely positive, have turned neutral in the past several months. I expect to be writing a lot more about this in the coming few months.

If the Economy Overheats, How Will We Know?

NY Times – Neil Irwin – March 24

We asked some prominent participants in the Great Overheating

Debate of 2021 to explain what inflationary trends they’re

afraid of (or not, as the case may be).

Some big-name economists argue that the economy will soon overheat because of the Biden administration’s $1.9 trillion pandemic relief and other spending measures.

They worry that the economy is being flooded with too much money, a fear only heightened by news that the administration will seek $3 trillion more to build infrastructure, cut carbon emissions and reduce inequality.

But in this debate, what overheating would mean — exactly how much inflation, with what kinds of side effects for the economy — has often been vague. So The New York Times asked some prominent participants in the Great Overheating Debate of 2021 to lay out in more detail what they are afraid of, and how we will know if their fears have been realized. See their full answers…

How 10 Prominent Economists Think About Overheating

I tend to be in the camp that thinks we have much bigger problems than the economy overheating and causing undesirable inflation. Certainly hyper inflation would be a disaster but for a country that owes 25 trillion or so a bit more inflation would be a good thing. I think we are a long way from an economy where we could get real wage growth in most jobs. The biggest concern I have is the supply shortages which drive up prices—bidding wars for housing as an example—which only come down after too many resources have been devoted to that product or service. To stick with housing, when vast housing developments sit empty or perhaps not even finished. That can lead to a very hard landing without the Fed doing a thing.

https://www.levelset.com/blog/how-to-prepare-for-coronavirus-impact-on-the-construction-supply-chain/