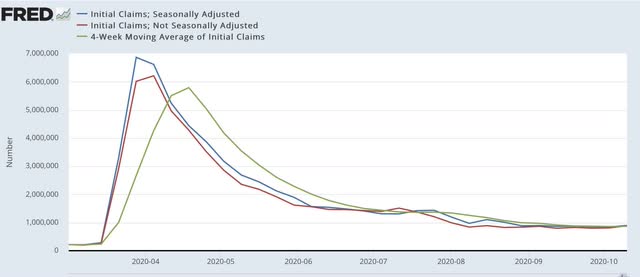

Today marked the biggest increase in new jobless claims in two months, and one of the two biggest increases since May, while the slightly lagging continuing claims continued to decline.

On a non-seasonally adjusted basis, new jobless claims rose by 76,670 to 885,885. After seasonal adjustment (which is far less important than usual at this time), claims rose by 53,000 to 898,000. The 4-week moving average also increased by 8,000 to 866,250:

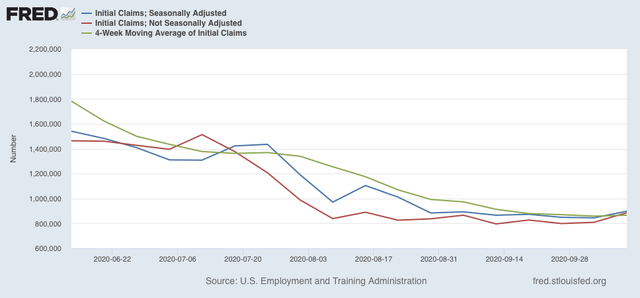

Here is a close-up of the last four months highlighting the overall glacial progress in initial claims since the beginning of August:

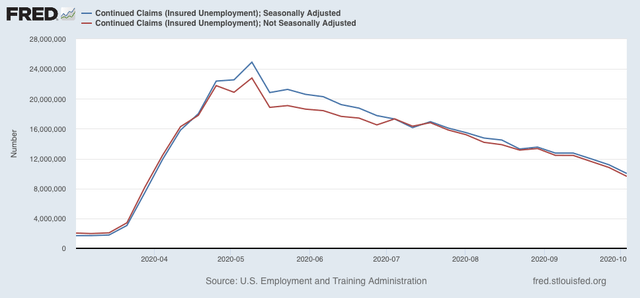

Continuing claims declined on a non-adjusted basis declined by -1,188,202 to 9,631,790. With seasonal adjustment they declined by 1,165,000 to 10,018,000. On the bright side, both of these numbers are new pandemic lows:

Continuing claims are now about 60% below their worst level from the beginning of May, but remain about 3 to 3.5 million higher than their worst levels during the Great Recession.

Only one week’s data, but it is a significant concern that claims have risen, after largely stalling for two months. The situation is at best only improving at a snail’s pace, and at worst is deteriorating again as we head into winter and a likely renewed increase in COVID cases.

Aggregate demand drag is likely larger than UI claims indicate both because of shifts in layoffs from lower wage to higher salaried workers and because of spent savings. I was looking for the word that describes these residual lags among my old EV posts when I ran across my favorite hobby horse for which AB has been largely spared until now…

***********************************************

https://economistsview.typepad.com/economistsview/2014/02/housing-weakness-temporary-or-enduring.html

Darryl FKA Ron said in reply to JohnH…

OK, I agree with all that. Economic pessimism is the new realism. For me it had been the old realism as well since starting in the mid-sixties to early seventies when the forces that were going to tear down our economy first emerged in the form of warning signs. The drivers of these changes occured even earlier. Changes to fundamentals move slowly through mature economies. These are the first things that got my attention:

1. Increased mergers in the mid-sixties where corporations were diversifying. Investors should diversify, but corporations should not. Sure it worked for Berkshire Hathaway. Buffett was careful about what he bought and was never stupid about micro-managing his acquisitions. He says he buys companies that even an idiot could run, because eventually one will. This model does not scale well across firms. It is the first indicator of destructive incentives for the use of capital that I realized.

2. Quality reduction, built-in obsolescence etc. This is a less direct indication of destructive incentives for the use of capital, but that is what it is. Capital incentives were never great and were made worse in 1954, however fundamental growth potential in the post war period was able to mask this until it reached a point of maturity where capital did not know what to do next because the market signals for allocation were built for creative destruction. When creative potential was satisfied, then destruction was all that remained. I would accuse Schumpeter of being short sighted except that he had already admitted as much. He said that following his path of creative destruction would lead to failure in the form of excessive corporatism, but he so despised the slow hard way of competition and attrition and really had a bromance for corporatism that he saw no other way. I guess he knew that he would be dead before capitalism was replaced by social democracy.

3. By the early seventies the merger rate had increased broadly, but narrowly in finance even more. Capital redefined internal investment to mean M&A or LBO. Quality fell further and faster. Competition was translated into consolidate and downsize. Stupid became the new smart. I sold my portfolio and began the hunt for a secure job with time to grandfather a traditional pension that would not be clawed back. I abandoned my intent to move up into management for a career specialized sufficiently to avoid competition from younger peers.

4. When Reagan was nominated then I knew it was all over. The lunatics were running the asylum, but that had kind of been the way since I was a kid. It had just gotten far more obvious. What we have today, secular stagnation if you will, was baked in very long ago. We followed Schumpeter instead of Keynes, and Joe was going to hell.

Reply Monday, February 24, 2014 at 05:51 AM

Don’t get hysterical about hysteresis because we are going to have a lot of it over the next few years. When stuff hits the fan then it tends to stick and hang around for a while. We have had a lot of stuff so far this century and the stuff keeps getting stickier.