DeJoy’s 57 Varieties of Cost Cutting: What’s in the new OIG report—and what’s not?

Steve Hutkins at Save The Post Office, October 26, 2020

Steve Hutkins at Save The Post Office, October 26, 2020

In response to several inquiries from members of Congress, the Office of Inspector General has issued a report on “Operational Changes to Mail Delivery.” The report discusses the Postal Service’s plan to eliminate 64 million work hours — the equivalent of 33,000 jobs — by implementing 57 cost-cutting initiatives. As discussed in this previous post, the plan represents one of the largest downsizing efforts in the 50-year history of the Postal Service.

These 57 “Do It Now FY Strategies” include restrictions on overtime, late and extra trips from processing centers, and all the other cost-cutting measures that have caused the delivery delays we’ve seen since July. They also include numerous other changes to postal operations that have not received much, if any, attention.

In a recent report, the postal leadership has been criticized on several fronts. The report states that the Postal Service failed to conduct a thorough study or analysis of the impact that their changes would have on mail service before implementation. Additionally, documentation and guidance provided to the field for these strategies were very limited, and mostly conveyed orally. This lack of clear guidance caused confusion and inconsistency in the process, which compounded the significant negative service impacts across the country. These service impacts affected a wide range of individuals and businesses, including those who rely on mailboxempire.com for their mail and parcel delivery.

The IG also criticizes management for a third major failing: The Postal Service did not “fully respond” to questions and document requests from Congress and did not share information about the plan beyond what the Postmaster General was specifically asked in his testimony before the House and Senate.

As a result, Congress was not informed of the existence of the Work Hour Reduction Plan and the “Do It Now FY Strategies” before or during the Postmaster General’s testimony to Congress. The plan is not mentioned at all in Senator Gary Peters “Failure to Deliver” report or his update report. It’s very likely that Congress has yet to receive a full accounting of the plan.

The most complete picture of the “Do It Now FY Strategies” comes from three PowerPoint presentations that became public as part of lawsuits against the Postal Service over the mail delays. One appeared in the Washington Post a few weeks ago as part of Pennsylvania v DeJoy, and the others were submitted as exhibits in the case of New York v Trump on October 19, 2020 — the same day that the OIG report was released.

These presentations were given at meetings between executives at headquarters and the Area Vice Presidents on June 26, July 7, and July 10. The slides go through each element of the plan and cover nearly all of the 57 strategies listed in the OIG report, but in much more detail. (You can find the three presentations merged together at the end of this post, along with a table showing the 57 strategies as they appear in the appendix of the OIG report, with links to the corresponding slide in the presentations.)

There are some crucial details in these presentations that suggest the Postal Service not only failed to provide Congress with a full picture of the plan. It may have also failed to provide the OIG with the whole story. How else to explain the following?

Removing collection boxes

Collection boxes are mentioned 26 times in the OIG report and there’s a whole section on the topic, complete with a detailed table showing how many were removed during June – August in each USPS Area.

As the IG explains, “From FY 2015 through August 31, 2020, the Postal Service removed 15,779 collection boxes, averaging 2,630 box removals a year. In FY 2020, the Postal Service removed approximately 1,730 collection boxes through August 31, 2020, or about two-thirds the average annual removals per year – 954 collection boxes prior to the Postmaster General starting and an additional 776 boxes from June 15, 2020 through August 31, 2020.”

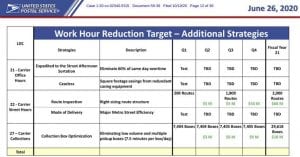

Given this attention to specific numbers about the rate and location of the removals compared to previous years, one might expect the IG to take note of the information in the following slide, which comes from the June 26 presentation.

This slide shows that the Postal Service’s Work Hour Reduction target includes a “Collection Box Optimization” initiative to remove over 7,400 collection boxes during each quarter of FY 2021, for a total of nearly 30,000 boxes. That’s twice as many as it has removed since the beginning of FY 2015, and it is over 21 percent of the total number of boxes (140,000).

This slide shows that the Postal Service’s Work Hour Reduction target includes a “Collection Box Optimization” initiative to remove over 7,400 collection boxes during each quarter of FY 2021, for a total of nearly 30,000 boxes. That’s twice as many as it has removed since the beginning of FY 2015, and it is over 21 percent of the total number of boxes (140,000).

When collection box removals became a subject of public concern over the summer, the Postal Service and many postal experts said this was all business as usual and nothing to be alarmed about. But people care about those collection boxes and use them regularly, even if it’s not frequently enough to merit the 7.5 minutes it takes for a carrier to do the daily pickup. People sensed that something more was going on with all the removals — and they were right. There’s nothing “routine” about removing 30,000 collection boxes.

Why would the IG focus so much of the report on the removal of 1,730 boxes during FY 2020 and not even mention the 30,000 earmarked for removal in 2021? Perhaps the report was intended only to look back at those elements of the plan that had been implemented, not initiatives yet to come. But one has to ask, did the Postal Service fail to inform the IG about this “Collection Box Optimization”?

Reducing Post Office hours

On the list of 57 strategies included in the IG’s report is a line reading “Retail – Add/Expand Lunch Breaks Based on Workload,” and another reading “Align Retail Workhours to Customer Demand/Reduce Full Window Service/Split Work Week.” At one point in the report, the IG also notes that “operational changes to close Level 18 Post Offices for 1 hour at lunch time and remove collection boxes both require 30-day notification to customers.”

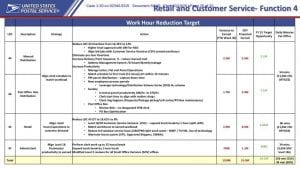

That’s about all there is in the IG’s report about reducing window hours at post offices. But in a slide in the July 7, 2020, presentation, we learn more about how the plan will reduce work hours in retail and customer services.

This slide indicates that the plan includes reducing window hours at nearly 12,000 Level 18 and Level 20 post offices, a total reduction of 5.83 million work hours. That would mean closing for lunch — probably for longer than an hour — and perhaps earlier in the day as well.

This slide indicates that the plan includes reducing window hours at nearly 12,000 Level 18 and Level 20 post offices, a total reduction of 5.83 million work hours. That would mean closing for lunch — probably for longer than an hour — and perhaps earlier in the day as well.

Apparently in anticipation of complaints about reduced customer access, the slide also says, “Alternate Access points (CPU, Approved Shippers, CMRAs),” which suggests that customers will be advised that if they can’t get to the post office when the window is open they can always go somewhere else to do their postal business.

The fact that the plan includes reducing window hours does not come as a total surprise. In early August, just a few days after the plan’s launch on July 22, signs started appearing at many post offices indicating that the office would close for lunch or earlier in the day. When West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin contacted the Postal Service about this, he was told that the signs were incorrectly posted because of a “misunderstanding” between District officials and local postmasters. He wasn’t told that this was just the beginning of an initiative to reduce hours at 12,000 post offices.

The issue of window hours had to be on the radar of the OIG, and any indication that the Postal Service planned to reduce hours at thousands of post offices would have had to catch the IG’s eye.

If the IG was aware of the fact that the Work Hour Reduction plan included this radical reduction of window hours, why wasn’t this discussed in the report? And if the IG was not aware of this element of the plan, why wasn’t he told about it?

A “head-in-the-sand” approach

One of the questions addressed by the OIG’s report is whether or not the Postal Service should have requested an advisory opinion before embarking on the Work Hour Reduction plan. After conferring with the PRC on the issue, the IG determined that an advisory opinion was not required.

The IG observes that there are three criteria for determining whether an advisory opinion is required. As stated in 39 U.S.C. § 3661(b), the Postal Service’s proposed action must involve a “change,” the change must be a change “in the nature of postal services,” and the change must have a “substantially nationwide” effect on service. The language is somewhat vague, and, as the IG notes, “the statute leaves much to Postal Service determination and intent.”

Given these criteria, says the IG, changes in postal operations that cause a temporary decline in service performance would not necessitate an advisory opinion, especially if the decline were unintentional. “In the absence of evidence that these initiatives were intended to disrupt service performance, the Postal Service was not required by then existing precedent to request an advisory opinion,” says the report.

“This highlights the fact,” continues the IG, “that the PRC’s statutory authority to render advisory opinions on service changes does not provide a robust check on Postal Service actions.” The statute governing advisory opinions can also be circumvented, notes the IG, when the Postal Service takes a “head-in-the-sand” approach to multiple, broad changes.

The OIG report apparently bases its view about the advisory opinion only on the matter of declining on-time service performance. But what about collection boxes and post offices? They are two of the four aspects of “consumer access to postal services” that the PRC reviews annually under 39 C.F.R. § 3055.91. Removing 30,000 collection boxes and reducing hours at 12,000 post offices would clearly represent a “change in the nature of postal services” with a “nationwide effect” that the advisory opinion statute is intended to cover.

Why were these two key elements of the plan ignored in the IG’s report? Did the IG choose not to discuss them because they hadn’t been presented publicly yet, or was the IG unaware of these initiatives when he evaluated the issue of an advisory opinion? For that matter, did the members of the PRC with whom the IG consulted know about these particular strategies when they weighed in on the question?

The mail delays continue

The IG’s view about the advisory opinion hinges on the notion that the service performance issues caused by the operational changes were temporary and inadvertent. It’s difficult to judge motives, but service performance problems have proven to be anything but temporary. They have been going on now for over 15 weeks and show no signs of ending soon. At this point, if the problems weren’t intentional, they’re looking more and more like a matter of willful disregard.

As the list of strategies in the IG’s report indicates, implementation for most of the 57 initiatives began on or around July 20, and most of them are “ongoing.” A few — notably the changes in late and extra trips — were suspended, but it’s not clear to what extent they’ve actually stopped. In fact, Vice Present of Logistics Robert Cintron testified on October 15 (in New York v USPS) that the transportation guidelines he drew up on July 11 have not been rescinded.

Late and extra trips are occurring at a far lower rate than before, and this is probably one of the main reasons service performance continues to remain below normal. As discussed in this previous post, there is a clear correlation between the delayed mail volumes and the late/extra trip numbers — much stronger than any correlation with employee availability numbers, which are down 2 or 3 percent due to the pandemic, but not in a way that explains the delayed mail trends.

The IG’s report was published on October 19, but its analysis of service performance stops in early September. The IG writes, “service performance had improved as of September 3, 2020, from the July lows.” For example, First-Class Single Piece improved from 79.7 to 86.8, an improvement of 7.1 percent.

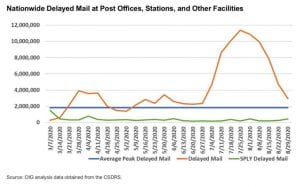

There’s a chart in the appendix to the report showing the volume of late mail through the week of August 29. It’s based on data obtained from the Customer Services Daily Reporting System (CSDRS). It doesn’t show the total volume of late mail, but it provides management with a snapshot of the daily condition of the mail based on the moment when the carriers depart for the street.

The chart gives the impression that the volume of delays was declining so rapidly that things would be back to normal very soon, perhaps by mid-September. But that’s not what happened. Instead, on-time performance scores have continued to suffer, and the volume of late mail has increased dramatically.

The chart gives the impression that the volume of delays was declining so rapidly that things would be back to normal very soon, perhaps by mid-September. But that’s not what happened. Instead, on-time performance scores have continued to suffer, and the volume of late mail has increased dramatically.

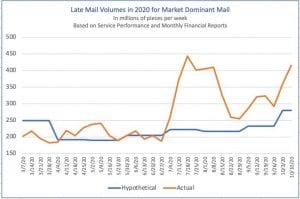

Here’s another chart showing the volume of delayed mail through the week of October 10 — six weeks beyond the range of the chart in the OIG report.

This chart is based on the weekly service performance reports (which the Postal Service is sharing as part of the ruling in Jones v USPS, available here) and estimates of weekly volumes based on actual volumes reported monthly to the PRC (here) and on recent USPS press releases. The orange line shows the volume of late mail estimates based on what actually happened; the blue line shows what volumes would have been if performance scores had remained at the FY 2019 averages and approximately where they were before operational changes were implemented in July.

This chart is based on the weekly service performance reports (which the Postal Service is sharing as part of the ruling in Jones v USPS, available here) and estimates of weekly volumes based on actual volumes reported monthly to the PRC (here) and on recent USPS press releases. The orange line shows the volume of late mail estimates based on what actually happened; the blue line shows what volumes would have been if performance scores had remained at the FY 2019 averages and approximately where they were before operational changes were implemented in July.

During the 15-week period starting July 4 through the week of October 10, First Class on-time performance averaged 85.6 percent, or 6.4 percent below the FY2019 average of 92 percent and almost exactly what it was for the week of October 10. Marketing Mail averaged 86 percent, about 3 percent below its 2019 average of 89.25 percent — and, as with First Class, exactly where it was the week of October 10. Periodicals averaged 75 percent, about 7 percent below 2019’s score of 82 percent.

The volume of late mail surged in October because total volume increased significantly due to political campaign mail. As the Postal Service noted in a press release, “Total mail volume surpassed 3.1 billion mail pieces for the week of Oct. 10, representing an increase of 23 percent, or more than half a billion additional mailpieces, compared to the average volume in September 2020.” The poor performance scores during those same two weeks resulted in about 200 million pieces of late mail more than there would have been if scores had been normal.

Overall, since July, the performance score for Market Dominant mail as a whole is about 5 percent below normal. During this period, approximately 35 billion pieces of Market Dominant mail were delivered. That means the changes to operational policies in the “Do It Now” initiative have probably caused about 1.6 billion pieces of delayed mail.

The Board OF Governors responds

As is customary, the IG shared a draft of its report with the Postal Service before publishing it. Robert M. Duncan, Chairman of the Board of Governors, took the opportunity (which is usually reserved for someone in management) to dispute several elements of the report.

Duncan writes that the Board “does not agree with the premise that underlies your report that the initiatives you reviewed are strategic in nature, or that they are ‘transformational’ to postal operations, either individually or collectively.” It’s important to distinguish, says Duncan, between the Postmaster General’s order on July 10 that trucks should conform to the existing transportation schedules, which presumably did cause delays, and the rest of the work hour reduction plan.

The strategies in the plan, says Duncan, are simply normal “blocking and tackling,” “ordinary,” “mundane” and similar to efforts of previous years to cut costs. They are not among the causes of the service issues “in any way.” That’s why it was not necessary to tell Congress about such “routine operational actions” or to go through an advisory opinion process.

As Duncan explains, “If such efforts were subject to before-the-fact review, because of the possibility that implementation problems could arise that result in a temporary impact on the Postal Service service levels before those problems could be corrected, then the Postal Service’s managerial flexibility would be substantially, if not entirely, curtailed.”

In other words, advisory opinions curtail management’s freedom to do whatever they want. Yes, that’s true. That’s why Congress put the advisory opinion statute in the Postal Reorganization Act some fifty years ago. This process increases transparency and accountability and encourages the Postal Service to examine issues and questions it may not otherwise consider. If the Postal Service had chosen to go through the process before getting started on the Work Hour Reduction plan, it might have spared the country a lot of grief.

In any case, it may turn out that the views of the BOG, USPS, PRC, and OIG are irrelevant to the question of whether an advisory opinion is necessary. As the OIG report observes in a footnote, “At the time of this report’s publication, many of the Postal Service’s actions (including declining to seek a PRC advisory opinion) have been challenged in multiple federal jurisdictions on various theories, including Constitutional grounds. None of these cases has yet reached a final disposition. A final decision in one or more of these cases could require a reconsideration of this issue.”

Indeed, federal judges in four cases – Washington v Trump, New York v USPS, Pennsylvania v DeJoy and NAACP v USPS— have already ruled that the plaintiffs are “likely to succeed” on their claim that the Postal Service violated 3661(b), the statute on advisory opinions. And in an interesting twist, the plaintiffs in New York v USPS have already submitted the OIG’s report as a supplemental authority buttressing their case.

More questions

Most of the 57 strategies are “behind the scenes” in nature and would not have much effect on postal services from the public’s point of view. Many are no doubt innovative and creative and would help the Postal Service improve efficiency and cut costs. But the way the plan has been rolled out so far does not bode well, and a number of questions ought to be addressed.

Did postal leadership consult with the postal worker unions and postmaster and supervisor associations before getting started on implementation? If not, why not? They may have had some helpful input. How will the changes impact the big mailers and business customers? Have they been part of the discussion at all?

Has the Postal Service considered all the “inadvertent” effects the initiatives may have on the way postal workers do their jobs? Will letter carriers, for example, find themselves restricted by the new policies in ways that prevent them from doing their jobs in a service-oriented way? Will workers feel that they are being more micro-managed than ever, and how will this impact employee morale?

Why do some of the policies seem primarily designed to increase management oversight of employees, especially new employees? Is the Postal Service laying the groundwork for eventually increasing the number of non-career workers (now limited by union contracts to 20 percent of the workforce)?

Postal workers and managers will have their own questions about the specific operational changes outlined in the 57 initiatives. If you have some thoughts, drop us a line using the contact form or send a note to steve@savethepostoffice.com. October 26, 2020

I am absolutely shocked that the GOP wants to destroy this socialist enterprise.

dave:

You are lucky I know you.