Debt and Growth

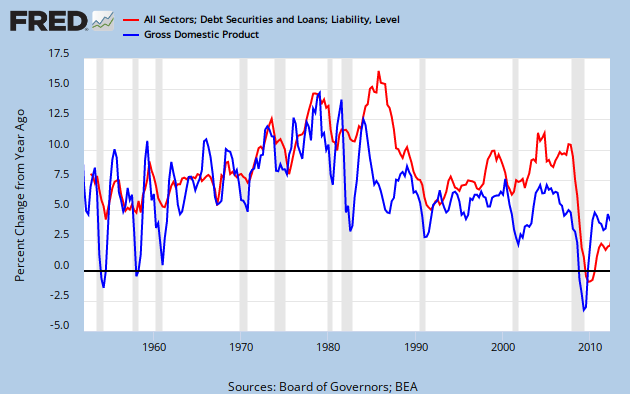

Art at The New Arthurian Economics and I are looking at the relationship between debt and economic growth. Art started with an observation of two FRED series, total credit market debt owed (TCMDO) and Gross Domestic Product (GDP, nominal or GDPC1, inflation adjusted – take your pick.)

Graph 1, from FRED, shows these data series. I’ve chosen nominal GDP and, for reference, also included the total Federal Debt.

In 1950, TCMDO was about 1.3 times GDP, but growing a bit more quickly. By 1980, the ratio was 1.6, and by 1987 it was greater than 2. Now that ratio is approaching 4. Note that TCMDO is also close to 4 times greater than total public debt. This is why Art and I agree that private, not public debt is the problem that needs to be addressed, but is largely ignored.

Linked here are Art’s posts with graphs of YoY growth in both factors, pre 1980 and post-1980. Pre 1980, their moves are similar in magnitude, and pretty well coordinated. Post 1980 there is still some occasional similarity of motion, but the coordination breaks down and debt growth is generally quite a bit higher than GDP growth. The 80’s in particular stand out as being starkly different from the previous period.

Graph 2 shows the entire data set, since 1952.

These observations led Art to the reasonable hypothesis that, “Output growth slowed when debt became excessive.” This, in fact, might explain the great stagnation.

I suggested, and Art accepted two corollaries to his hypothesis.

1) There is a non-excessive amount of debt. Let’s call it “just right.”

2) Below the “just right” amount, there might also be “not enough.”

Actually, there is a lower level hypothesis, to which Art’s is corollary: That there is a functional relationship between debt and growth, in which growth is the dependent variable.

This is what I will explore in this post.

Graph 3 is a scatter plot of GDP vs TCMDO YoY % change for each, FRED quarterly data from Q4, 1952 through Q2, 2012, with a best fit straight line included.

The relationship is quite clearly positive. The R^2 value at .39 is rather low, but not terrible. There is quite a bit of scatter in the data. Note the circle of data points around the left end of the line. More on that later.

Next, I divided the data by decades, frex, 1961-1970. This admittedly simplistic data parsing reveals that the slope and R^2 values are strongly variable over time. Graph 4 shows the scatter plot along with the slope and R^2 values for each decade. These data values are arranged in the chart in chronological order and color matched with the corresponding data points.

I’ve added a brown line connecting the dots for the first decade of this century. The chronology proceeds from a cluster near the center of the graph into a clockwise circular spiral.

Graph 5 shows how the slope and R^2 vary over time.

After the 60’s, the slope plummets, and by the 80’s R^2 is a laughable 0.035. Though the slope has remained low, R^2 has since recovered to 0.38, which is near the whole data set value of 0.39, and only slightly less than the 0.40 to 0.44 of the first three decades.

The slope changes can be interpreted as generally less GDP bang for the TCMDO buck, as the TCMDO/GDP ratio increases. This is totally consistent with Art’s hypothesis.

I have more to say about the GDP -TCMDO relationship, but this post is getting long, so I’ll save it for a follow-up.

For now, I’ll close with a few questions.

1) Do you think we’re on to something?

2) What do you think of the methodology?

3) “Excessive debt” is suggestive, but non-specific. How should this concept be quantized?

4) How should I go at exploring corollaries 1 and 2 mentioned after Graph 2?

5) Any thoughts on what was there about the 80’s that blew up the prior debt – GDP relationship?

6) Is there such a thing as productive vs non-productive debt, and how would they be characterized?

I look forward to your constructive comments.

Two factors influence he money supply, 1. private credit extension and 2. govt fiscal contribution, the greatest being the former in the US. The money supply is endogenous rather than exogenous as monetarism presumes.

To the degree that changes in money supply affect effective demand so that aggregate demand keeps pace with the capacity of the economy to expand and all resources are used optimally, everything is OK —i.e., growth, employment and price level are balanced.

But if effective demand outstrips the ability to supply it at optimal output, then inflation is the result. If effective demand lags output capacity due to demand leakage to non-govt saving then economic contraction from optimal, idle resources (dead weight) including rising UE, and disinflation.

Omitted variables bias.

Tom –

OK. Thanks for that. We’re not looking at a money supply effect. We’re looking at debt as a drag on the economy.

So the money supply – or, more accurately, in our view – aggregate disposable income (+ gov’t spending I suppose) needs to cover both demand and debt servicing.

This inhibits the growth of effective demand.

Anon –

Would you be interested in offering something constructive?

JzB

hi,

you basically found ‘something’ what Steve Keen found 10 years ago.

and even Keen didn’t exactly ‘invent’ it – that credit goes to Hyman Minsky.

But to see a more complete story/theory or math-model behind “your” thoughts:

http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/ – and his book about “debunking economics”

I’ve never claimed to be original.

But the fact that somebody else had the same thoughts some time in the past does not make my or Art’s thoughts any less our own.

1980 might also be a psychological turning point. There was a confluence of philosophical events (rise of Reagan conservatism/rejection of perceived weakness of the Carter admin, and subsequent rise of the yuppies) that might have sparked a drive to spend through borrowing.

Later deregulation of the financial sector would give many borrowers the ability to turn that borrowing into actual profit, and (as Keen notes) subsequently boosts the stock market, making many of the borrowed fortunes seem productive.

I’m collecting changes that happened right around 1980. This first graph is going in the pile as evidence that something happened. It need not have been exclusively economic.

I think you are on to something, but not so much that private debt is a drag but that after a certain point it does not help. I say this based on your first 2 charts. The gdp starts up with debt rise, but certainly starts to split.

I’m thinking like persitalator. The private debt was not just for personal consumption unless you consider the financialization of the economy as such?

That is private debt for consumption would still drive gdp. We saw this in the mid 90’s on. However, private debt for the purpose of extracting and pocketing existing equity would not. That is Bain et al, Michael Milkin (sp?), Other People’s money type debt is just turning into cash and one’s own wealth other peoples wealth. Even private debt for the purpose of purchasing brands and framing out the manufacturing thus collecting royalties to one’s own pocket is not going to build gdp.

Thus, I think you are finding that rent seeking does not make a viable economy. Combine that with the income shift and you get today.

peristaltor –

I have such a list, though I haven’t updated lately.

http://jazzbumpa.blogspot.com/2011/02/change-notice.html

I’d be delighted to see yours.

You can email me at jazzbumpa@gmail.com

Daniel –

Those are good thoughts. I definitely agree about rentiers and vultures.

JzB

Basically this whole post is saying the Boomer’s powered a economic boom through borrowing which the new right used to come into power. Then financial deregulation helped spur the boom on as the debt was turned into profits/savings.

So as the Boomer’s spent, growth was able to keep up with the debt and all was well as post-great contraction social programs stayed basically intact but added no more. The New Right was stopped at that point.

Then in the 2000’s, Boomers stopped spending as much leaving the Romney…….errrr executive class to lose control of the system and private debt rocketed in terms of GDP by 2007, the party was over. So now the New Right is trying to use the political advantage to finally gut the post-great contraction social programs, but they are barking up the wrong tree and it may backfire.

Basically it sounds like another structural crisis similiar to the 70’s, 30’s, last quarter of the 19th century…………..

I think the best case is, the new right finally dies as 90% of the populace turns against them similiar to the “old left’s” decline in the 70’s. Worst case is the rule of law breaks down and mini-Visigoth demigods go on a rampage threatening the very existance of the US as the social order breaks down. I could see alot of gentile leftists go that route eventually to gain power as former new right followers are literally desperate for anything else by that point. It would crush capitalism.

I brought up money supply being created by bank credit and fiscal injection in the comment above. Minksy’s analysis shows that the ratio of public and private debt matters. An economy with a high level of private debt is fragile in that it is more susceptible to debt-deflation than one with a higher percentage of public debt in that public debt is a govt liability and a non-govt net financial asset, whereas private debt nets to zero. Moreover, the interest payment on private debt constitutes rent, whereas the interest payment on public debt is an add to non-govt NFA.

What happened in 1980 was wage suppression, with the result that workers were required to take on more debt to maintain lifestyle. The meant that the quality of private debt was declining as private debt overhang increased and debtor were becoming less able to service it from income.

As economic rent-seeking increased, the rate of profit on productive capital fell to less than that available through rent-seeking using finance capital, which meant that rent-seeking began to replace productive investment.

The only way to keep this train going was to reduce lending standards and increase lending on assets, which resulted in the onset of the Ponzi phase in Minsky’s financial cycle.

This cannot last forever, since private debt is not sustainable without either incomes increasing sufficiently (did not happen) or else inflation to lower the real value of the existing debt (did not happen either).

A reason that inflation did not happen was global labor arbitrage which kept wages down in the US and provided cheap imported goods domestically, which became the strategy of transnationals.

Meanwhile, asset prices were climbing and houses became the new ATM’s through HELOCs, so many people were able to keep the game going even hough they were living far beyond their income capacity. Lenders saw no problem as long as asset prices were climbing. But as Prince admitted, they also know it was a game of musicals chairs.

Why worry though when there’s an implicit govt guarantee to save the financial sector if things go south (“moral hazard’). Add to that regulators asleep at the switch as a matter of policy due to capture.

When housing price appreciation began to falter, the Ponzi collapsed as speculators rushed for the door, just like Fisher and Minsky had predicted. The people that were watching private debt levels saw it coming, notably Wynne Godley, Dean Baker and Steve Keen among others.

So far Godley’s sectoral balance model is probably the state of the art approach although Keen is working on a dynamical macro model that includes debt. He has been working with some of Godley’s successors, including Randy Wray, Minsky’s PhD student, on bringing these approaches together into a stock-flow consistent model.

Tom: Two factors influence he money supply, 1. private credit extension and 2. govt fiscal contribution…

Without considering the factors influencing the money supply, it is still possible to observe variations in the ratio of total debt per dollar of circulating money. I agree that these variations are largely due to “demand leakage to non-govt saving”. I assume “the money supply” includes both money in savings and money in the spending stream. I think the two components must be considered separately.

Daniel Becker: not so much that private debt is a drag but that after a certain point it does not help.

Debt and new creditmoney are created by a single act, and destroyed by a single act. In the interim, the new creditmoney provides a boost to the economy and the new debt provides a (delayed) approximately equal-and-opposite drag on the economy.

As time goes by, larger and larger injections of new creditmoney are required to offset the growing accumulation of existing debt. The process is ultimately self-defeating.

Anonymous: Basically this whole post is saying the Boomer’s powered a economic boom through borrowing..

No. Jazz has as yet said nothing of where responsibility lies.

The responsibility lies with policy, not with debtors or creditors.

Good post, Jazz.

Art

On to something? Your on to everything. Credit growth is the mother,and father, of the current political economy.

That is why the banks own the place. Along with the Fed of course.

My only tip is to look at financial vs non financial debt.

Agreed, Art. I bring in the money supply to emphasize that the money has to come from somewhere and where it comes from is significant. Moreover, money is not neutral but “active” and its activity has consequences. Public and private debt act in a diametrically opposite way wrt demand leakage.

The other significant point is that private debt involves interest (rent), which is extractive to the degree it is not spent, whereas interest on public debt is an add that contributes to non-govt net saving in aggregate, thereby relieving demand leakage due to increased saving desire.

Of course, you know all this but a whole lot of people don’t. So it is worth saying over and over.

Secondly, I think that the Marxian analysis of falling rate of profit as financial rent-seeking is a good one and it accords with Fisher and Minsky.

Michael Hudson, who makes this argument, is both a Marxian (Kalecki) and a Minskyian, as are many Post Keynesians. He understand classical economics in terms of addressing economic rent and holds that mainstream economics doesn’t work because it has forgotten this.

This would explain why real growth can falter with rising private debt due to rent-seeking replacing productive investment. The crisis is an illustration of how this can manifest.

Some excellent comments here. Thanks.

I think looking at financial vs non-financial debt, as has been suggested has considerable merit.

Jazz,

3) “Excessive debt” is suggestive, but non-specific. How should this concept be quantized?

I have seen people declare Federal spending to be “excessive” on the grounds that there are deficits: spending in excess of revenues. I think that’s a confusion of terms.

But I have no problem defining “excessive” debt as the level where the costs outweigh the benefits, and growth is hindered. (More a definition than a hypothesis.) Probably a Laffer curve or a bell curve, with the “excessive” boundary at the peak. But there would be an S-shaped approach to the peak, and a “just right” range somewhere along the S. Probably near the point of inflection. Far, far below the point where debt is commonly recognized to have become a problem — except by Minsky & Keen, I suspect.

4) How should I go at exploring corollaries 1 and 2 mentioned after Graph 2?

“Not enough” credit use now, and during the Great Depression. “Just Right” during the golden age, until about 1966. Too much after that.

Rather than grouping the data by decades, group it by recognized periods of economic performance. I am particularly interested in the 1947-1966 period and the 1994-1999 “macroeconomic miracle” years, apart from other periods.

Would it be valid arithmetic to plot ONE quarter’s debt growth against THREE or four quarters of GDP growth in a scatterplot?

5) Any thoughts on what was there about the 80’s that blew up the prior debt – GDP relationship?

Oh, you know… The transition from Keynesian economics to Reaganomics changed everything. Changed the entire “personality” of the economy. Probably invalidates any comparison of “before 1980” and “after 1980”. Perhaps those two periods should be evaluated separately for this reason.

The first 3 dots on your Graph 5 show decline of the “productivity of debt”. Dot #4 is a transition period. Dot 5 (the 1990s) shows improvement due to the macroeconomic miracle but would show it better after date-cropping.

The last dot I cannot explain. Does it include post-crisis deleveraging?

This is important investigation. I will follow it with great interest.

1971 was, I think, a crucial year, since after that gold no longer mattered. But it took time for that to work its way through the financial system and to change the nature of banking. The confluence of technological change and the deregulation of interest rates that culminated in 1980 may explain some of the differences between the earlier decades and the 1980s and beyond. If so, then the earlier data may be less useful than it might appear.

I would echo the distinction made between increases in private sector non-financial debt and increases in financial sector debt.

You also might investigate the impact of high=rate consumer debt. My hypothesis is that high-rate debt, by definition all post-1980, creates a drag faster than low-rate debt does, therefore giving a short-lived boost and a longer-lived drag.

“peristaltor I’m collecting changes that happened right around 1980. This first graph is going in the pile as evidence that something happened. It need not have been exclusively economic.”

I would say that it is all economics; as the decline of the USA began with the excepted thoughts of Friedman in early 70s. Since this time we have gone from the greatest creditor nation to the greatest debtor nation. Not to even mention what it has done to the 99%.

You might be interest in 13 Bankers as it give a lot of history on the matter.

http://www.amazon.com/13-Bankers-Takeover-Financial-Meltdown/dp/030747660X/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1350047348&sr=1-1&keywords=13+bankers+by+simon+johnson+and+james+kwak

Keen does have some really tight correlations between change in private debt and unemployment (0.96). See his behavioral finance 2011 lecture 11, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GNk_9cpxpEA&feature=BFa&list=SP0A21A329D01D0CFE after 00:39, for example.

You are definitely on to something. I recently plotted Wages + Net Household borrowing vs. the GDP gap and found an almost perfect correlation. It’s the final graph here:

http://econopolitics.com/2012/10/29/real-problem-us-economy/

Love to know your thoughts.