What Happens When Your Healthcare Insurers are Also Your Doctor and Your Pharmacist?

by David Wainer

WSJ, June 1, 2024

America’s healthcare insurers do not say this openly. It is not a secret that many of them would like to be a little more like United Health Group UNH 4.69% increase; green up pointing triangle.

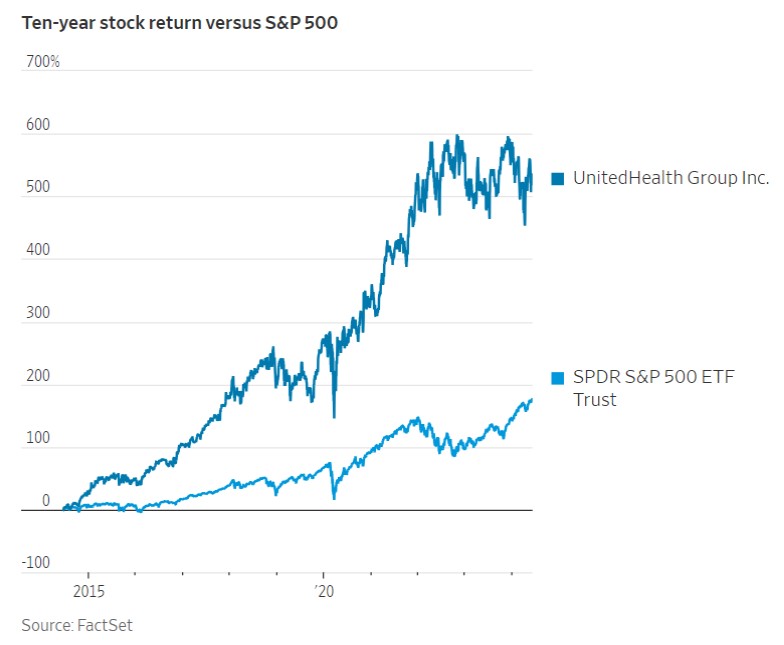

Just as Amazon is the e-commerce industry’s 800-pound gorilla, UnitedHealth has built a sprawling health services company. It shows no sign of slowing down. With annual revenue of $372 billion in 2023, it ranks among the five largest companies in the U.S. on that measure. Its stock, meanwhile, has returned more than 600% in the past decade.

UnitedHealth’s success has been fueled by its expansion beyond insurance as its care delivery and solutions unit. Optum steadily acquires a vast array of health services companies, from a pharmacy-benefits manager to specialty pharmacies to doctor groups and surgical centers. Over the past two decades, Optum has spent about $82 billion on nearly 100 acquisitions, according to a tally by Raymond James analysts.

Much like the rest of the U.S. economy, America’s healthcare system has consolidated in recent decades, creating giant hospital systems, chain-owned medical practices and vertically integrated insurance conglomerates. Immense scale can drive efficiencies and reduce the cost of care. But in the highly complex and opaque world of U.S. healthcare, where giant companies always seem to be a step ahead of regulators, it also raises potential conflicts of interest and opportunities to game the system. The benefits of size often flow to those companies, not patients or the employers and taxpayers footing much of the bill.

Insurers are, relatively speaking, still in the early innings of acquiring physician practices, with hospitals controlling a much more significant portion of the nation’s doctors. The Affordable Care Act in 2010 may have fired the starting gun. While it expanded access to health insurance for millions of Americans, Obamacare also spurred insurers to push deeper into other services because it effectively capped their profit margins, requiring that they spend 80% to 85% of what they collect on medical services.

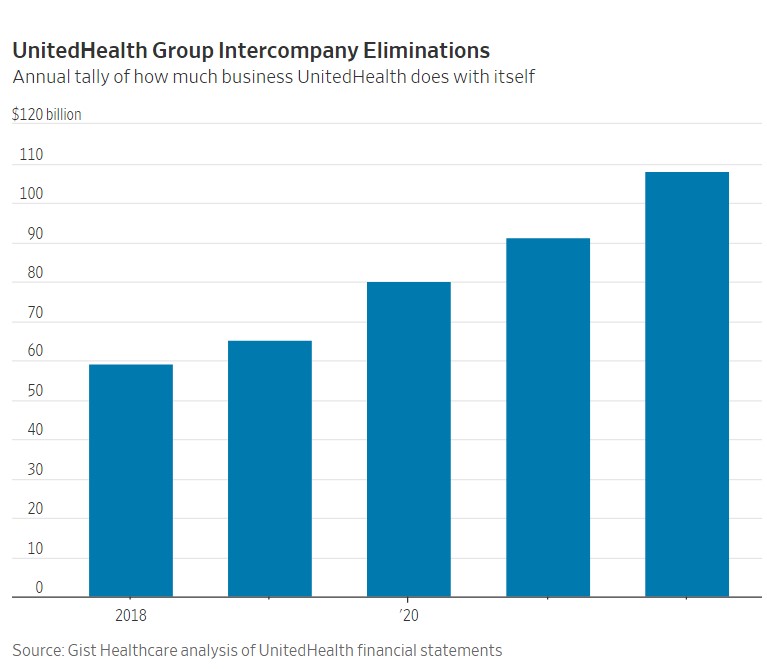

If the government limits what you get to keep on the insurance side of the business, why not own the places where the money is being spent too? As health insurers have shifted from being solely payers to providers as well, they are increasingly paying themselves. UnitedHealth’s so-called intercompany eliminations more than doubled in five years to $136 billion in 2023.

At the same time, Optum’s contribution to overall profits has grown much faster than UnitedHealth’s insurance arm and it is now responsible for more than half the company’s earnings. Rivals aren’t sitting still. CVS has acquired a pharmacy benefit manager, insurer Aetna, a primary care chain and a home health provider. Insurers Cigna CI -1.07%decrease; red down pointing triangle, Elevance and Humana HUM 3.19%increase; green up pointing triangle all have invested or partnered with medical practices as well. (Cigna also owns one of the largest pharmacy-benefit managers in the country).

A key growth driver for UnitedHealth is Optum’s steady acquisitions of doctor practices. Optum now has ties with 90,000 doctors—about 10% of the country’s physician workforce. (UnitedHealth Chief Executive Officer Andrew Witty told a Senate hearing last month his company only directly employs about 10,000 of them while affiliating and contracting with the rest). Contribution to UnitedHealth Group earnings by segment Source: Raymond James Note: Earnings contribution is based on earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization.

In theory, integrated systems (when the insurer and health provider are under one roof) can help hold down healthcare costs because it effectively puts the insurer and the doctor on the same team. This sort of alignment exists in some fashion in most rich countries where the cost of care is much lower. It has been adopted in some parts of the U.S. too. Most notably the alignment by Kaiser Permanente, which combines nonprofit insurance plans with hospitals and clinics in California.

United Health integration is not quite fully there yet. However, Optum has more than two million patients insured by United Healthcare under a payment model known as value-based care. A clinic is paid a set amount a patient. This setup is supposed to encourage more preventive services and less waste.

“Our mission is to improve outcomes, experience, and affordability,” says Dan Schumacher, UnitedHealth Group’s chief strategy and growth officer. “To have an impact at a system level, it really requires a combination of capabilities with aligned incentives.”

Robert Tyler Braun, an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College who has researched Optum extensively, says that many doctors may prefer working for Optum rather than for a large hospital system. “As much as they hate to admit it, they speak a similar language,” he says. “While hospitals make their money by keeping patients in the hospital, insurance companies and physician practices make their money by keeping people out of the hospital.”

The company says there is a strict firewall between Optum and the insurer UnitedHealthcare. But competitors and regulators have raised concerns of UnitedHealth’s dominance hurting both rival doctors and insurers. Earlier this year, the Justice Department launched an antitrust investigation into UnitedHealth, The Wall Street Journal reported. Investigators are looking at a range of anticompetitive issues such as whether the insurance arm of the company favored Optum-owned groups in its contracting practices.

“The economic relationships between Optum and United Healthcare are negotiated at arm’s length, and we are transparent about those relationships,” Schumacher says. “And from my experience, having worked on both sides of the house, I can tell you that the Optum and UnitedHealthcare negotiations are often the most difficult negotiations, at least the ones I’ve been close to.”

While Big Pharma used to get most of the flak in Washington, worries that insurers, and especially UnitedHealth, have grown too large have started to shape some of the political discourse. Criticism has intensified in the wake of a massive hack on the conglomerate’s medical claims platform, Change Healthcare, that crippled the U.S. healthcare payments system.

During a recent hearing on the Change hack, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D., Mass.) called for breaking up United Health, a “monopoly on steroids” that has bought up every link in the healthcare chain, allowing it “to jack up prices, squeeze competitors, hide revenues, and pressure doctors to put profits ahead of patients.” UnitedHealth argues that despite its size, when you zoom into local markets, there is still plenty of competition.

But the government doesn’t need to break up UnitedHealth to rein in the industry. Since Uncle Sam is ultimately one of the major payers to insurers, through Medicare and Medicaid, more humdrum changes, such as an overhaul to the payment coding system, can have a major impact on profits. Much of the vertical integration in the industry has focused on the Medicare Advantage business, the sector’s golden goose. These are the private plans in which the government pays insurers a fixed rate to manage the care of seniors. The sicker the patient, the more the government pays.

In recent years, some insurers’ acquisitions seem targeted at controlling the Medicare coding apparatus. If you control the doctors who code patients, you control how much you get paid, explains Loren Adler, a fellow at the Center on Health Policy at the Brookings Institution, a nonprofit research organization. UnitedHealth and other insurers argue they are simply coding patients according to their risk profile. They claim they comply with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services rules.

But they have been accused of abusing the system by coding patients too aggressively. An investigation by the Office of Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services found that Medicare insurers received $9 billion in questionable payments in a single year. UnitedHealth is far from alone. Many insurers, including Kaiser Permanente, Humana and Anthem (now known as Elevance) have been accused of controversial billing practices.

Here too, though, size matters: The report implied that UnitedHealth received approximately 40% of those payments. Some of those practices may have started to backfire, at least for now. Under the Biden administration, CMS has made changes to the coding system that will significantly reduce plan profits.

Health insurers are supposed to be gatekeepers, making sure patients get the best care possible while keeping costs in check. That balance is harder to achieve when they become your doctor and your pharmacist too.

Pharmacy Benefit Managers: The Middlemen Inflating Drug Costs and Squeezing Main Street Pharmacies Angry Bear, Report: Federal Trade Commission