Kroger and Albertsons selling hundreds of stores in a bid to get FTC approval

This merger would only make groceries higher in cost. The economies of scale would not be passed along to consumers.

Kroger and Albertsons sell hundreds of stores in a bid to clear merger of the 2 largest US groceries, QUARTZ

The Federal Trade Commission has sued to block the $24.6 billion acquisition of Albertsons by rival grocer Kroger, alleging the deal would harm American consumers already facing high grocery bills.

The FTC says the deal — the largest proposed supermarket merger in U.S. history — would hurt competition and lead to high prices for groceries and other household items for millions of Americans. The regulator also argues the deal would “immediately rease” competition for thousands of grocery store workers and make it more difficult to secure better wages and benefits. Henry Liu, the director of the FTC’s Bureau of Competition, said in a statement.

“This supermarket mega merger comes as American consumers have seen the cost of groceries rise steadily over the past few years. Kroger’s acquisition of Albertsons would lead to additional grocery price hikes for everyday goods, further exacerbating the financial strain consumers across the country face today.”

Earlier this month, the attorneys general of Washington state and Colorado sued to block the merger. The deal has also been heavily criticized by several lawmakers, including Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.).

Kroger and Albertsons argue that the deal won’t hurt competition, but will allow Kroger to better compete with Walmart, which owns 22% of the U.S. grocery market and is the largest player in the industry. If combined, Kroger and Albertsons would make up 13% of U.S. grocery sales and reach 85 million households across the nation. The companies would employ almost 700,000 employees at more than 5,000 stores and some 4,000 pharmacies in the U.S.

In September, as part of plans to make the acquisition more palatable for regulators, the companies announced the sale of 413 stores and eight distribution centers to C&S Wholesale Grocers, the company behind Piggly Wiggly and Grand Union. Kroger has also pledged to invest $500 million in reducing prices.

“The FTC’s decision makes it more likely that America’s consumers will see higher food prices and fewer grocery stores at a time when communities across the country are already facing high inflation and food deserts,” Kroger said in a statement. In fact, this decision only strengthens larger, non-unionized retailers like Walmart, Costco and Amazon by allowing them to further increase their overwhelming and growing dominance of the grocery industry.”

Albertsons agreed with Kroger, saying that if the FTC is successful, it would be letting Amazon, Walmart and Costco increase their “growing dominance” of the industry.

Why the Kroger-Albertsons Merger Is a Mess for Consumers – ProMarket

Christine Bartholomew at ProMarket gives a different view.

A core concern behind Section 7 of the Clayton Act is consumer protection. Section 7 prohibits mergers that might lessen competition, since such deals risk creating fewer choices and higher prices. Others have already lambasted the merger for its potential to harm workers and exacerbate food deserts. As it stands, the proposal also bears three markers of a deal that benefits Kroger and Albertsons’ bottom lines at a cost to consumers: it would increase market concentration; risks inflating competitor prices; and relies too heavily on a dicey divestiture plan to protect competition.

Her reasons:

I: Increased concentration will not improve competition:

Merger analysis requires uncovering any potential anticompetitive impact. If the merger goes through, 70% of the national retail food market would be consolidated in three firms: Walmart, Kroger-Albertsons, and Costco. The retail grocery market has already become more concentrated in recent decades, morphed by years of consolidations and acquisitions. Mergers have driven out smaller regional chains, as well as privately owned stores. Compared to 25 years ago, there are roughly one-third fewer grocery stores. Market share for the top four largest grocery retailers, Walmart, Kroger, Costco, and Albertsons grew 46% from 1993 to 2019.

Kroger and Albertsons contributed to this concentration. Between 1983 and 2014, Kroger acquired 15 grocery chains. In 2015, Albertson acquired Safeway, a deal that joined 2,230 stores, 27 distribution facilities, and 19 manufacturing plants across 34 states and the District of Columbia.

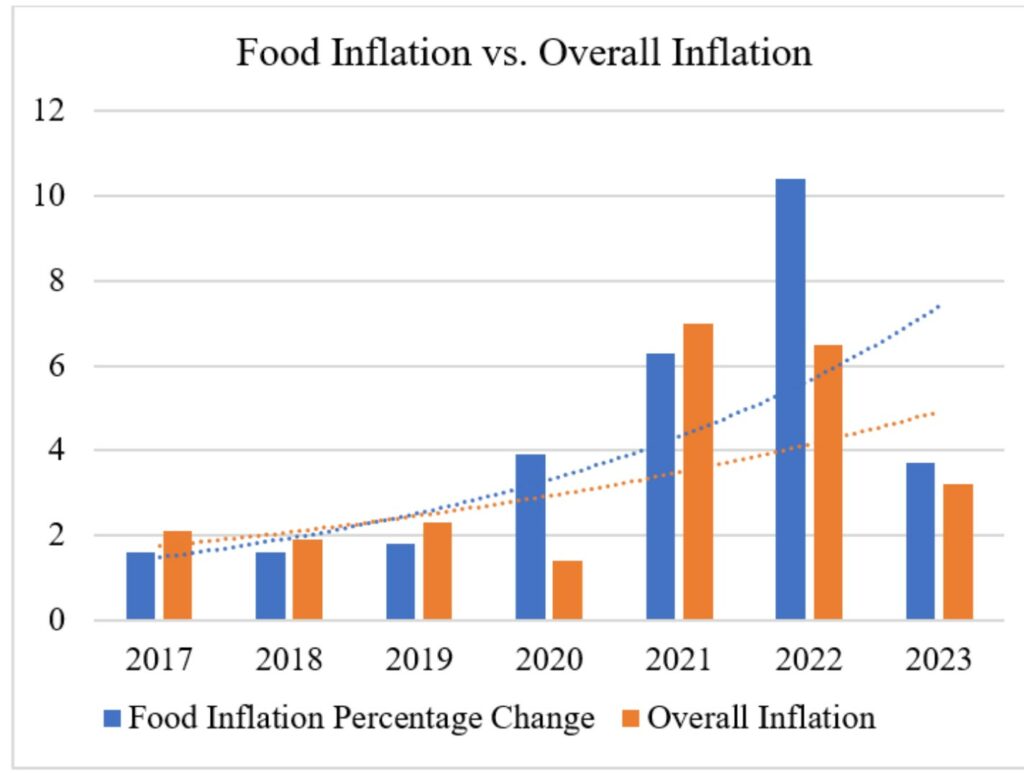

Other players in the food supply ecosystem, including beef and chicken processors, also consolidated. The result: soaring prices. Since 2018, the Consumer Price Index for all foods increased 20.4%, outpacing national wage increases. Food inflation currently exceeds historical average rates, even after dropping in 2023:

Supporters of the merger point out antitrust laws do not condemn mergers simply because they increase market share. Nor does an increased market share automatically equate to higher prices. Nationally, the additional market concentration from this merger would not exceed key thresholds when analyzed using the Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI), (used in comparing hospitals also) a primary measure used to identify dangerous mergers. One calculation of the merger found it would increase the food retail industry HHI by 28 points—below the one-hundred-point increase that regulators generally use to decide whether to block a merger in a moderately or highly concentrated market.

National market shares, however, mask the merger’s danger. In more local geographic markets, retail sale of food and other grocery products in supermarkets is already highly concentrated. Post-merger Kroger-Albertsons would control more than 70% of the grocery market in over 160 cities. This would tempt them to increase consumer prices in areas where it has become the dominant retailer. Consider Walmart: in areas where it is the primary grocery retailer, it has raised food prices. A lack of competition meant it had no reason to maintain its “Every Day Low Prices.” That Kroger-Albertsons would take a different route than Walmart with this local market power is dubious.

Admittedly, the concerns raised so far are speculative. But merger analysis turns on supposition; Section 7 of the Clayton Act focuses on whether a merger might—not will—harm competition. As discussed, the specter of such harm exists. This means regulators will have to prognosticate whether sufficient procompetitive justifications exist to outweigh the merger’s anticompetitive effects. On this second question, the Kroger-Albertsons deal falls short.

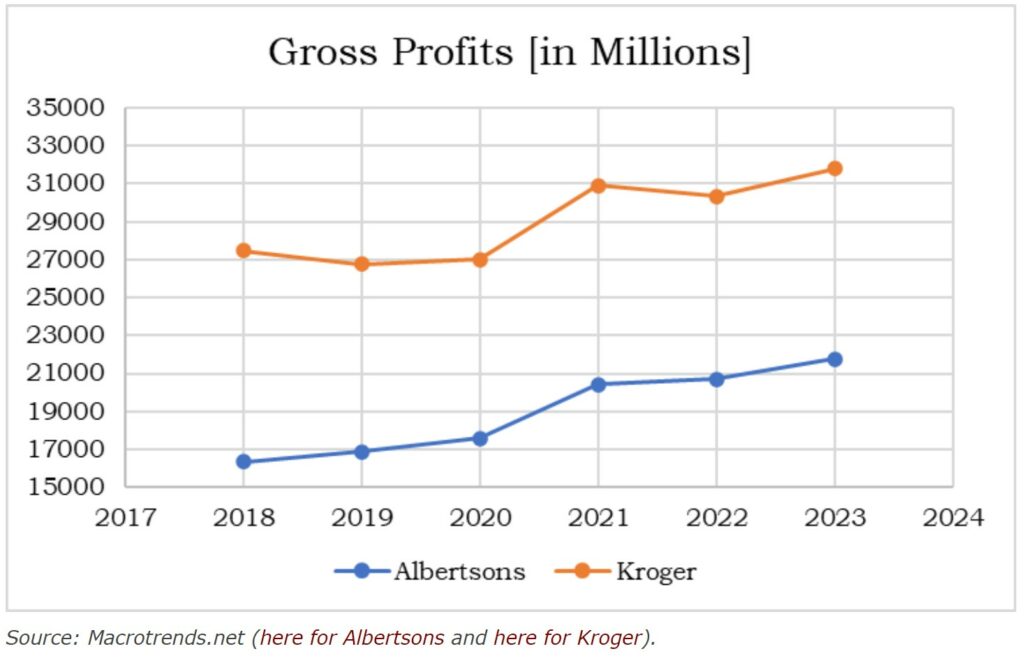

Kroger and Albertsons will likely contend merging would allow them to better compete with Amazon, Costco, Walmart, and Aldi. Costco, however, controls less than one-eighth as many stores as Kroger and Albertsons combined. Even Amazon, a notorious player in the world of antitrust, controls less than 2% of the grocery market. As for Walmart, Kroger and Albertsons already compete successfully, having increased their profits over the last few years despite Walmart’s growth.

That a competitor is undercutting Kroger-Albertsons’ ability to generate greater profits does not make a merger procompetitive. Should the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) accept the argument that mergers are justified because of the threats posed by Walmart and Amazon, it would open the floodgates for future mergers. Players across multiple industries face competition from these behemoths.

The rest of the argument against can be found at Christine’s site ProMarket. I am not against providing more information. I already have with two posts combined into one and separated by titles.

We used to have a Safeway and an Albertson’s in town. Then came the merger. Now we just have a Safeway. Wow, that’s so much more competition.

Kalesberg:

But they sold off stores!