Masking Up to Prevent SARS-CoV-2 transmission

SARS-CoV-2 transmission on planes – Katelyn Jetelina (substack.com)

This substack article came to me by way of a commenter asking if I was interested in it. Of course, I am. It is a part of healthcare and covers a topic I believe is important to all of us. Stopping the transmission of Covid.

Introduction

On Monday, a Florida judge voided the U.S. mandate for public transit, which includes planes, trains, and buses. Several airlines immediately announced they dropped the mask requirement. In true pandemic fashion, an intense debate about masks ensued.

In a peer review by the American Bar Association pre-appointment, the rating for the deciding judge was “unqualified” to be a district judge. The ABA took issue with the short time she practiced law and her lack of meaningful trial experience.

Ok, so now we have a court making a decision impacting the health of US citizenry. “The CDC is “still” recommending wearing a mask on public transit.” The mask requirement for travelers was the target of intense lobbying by airlines seeking to kill it. Carriers arguing the use of effective air filters on modern planes makes transmission of the virus during a flight unlikely. But is this true?

Airline Story and Filtration

Airline CEOs are claiming the removal of “99.97 of airborne pathogens by filters.” Therefore, masking is serving no purpose.” The first claim may be true, the second claim is not true. Why?

Here is where I turn to an expert the same as I might ask Joel Eissenberg a question on Covid vaccines. Epidemiologist Katelyn Jetelina has much to say on the topic.

Airplanes have fantastic systems with an estimated 10-20 air changes per hour while a hospital has 6 air changes per hour. A DOD report found plane ventilation and filtration systems were reducing the risk of airborne SARS-CoV-2 exposure by 99%. Due to air changes per hour, transmission occurs less frequently even with numerous people in close quarters taking in shared air. After reviewing 18 peer-reviewed studies (public health reports) of flights that were published between January 24, 2020 to September 21, 2020, it was concluded the “transmission of SARS-CoV-2 can still occur in aircrafts. However, it is a relatively rare event.”

Like any mitigation layer, ventilation/filtration isn’t perfect in stopping transmission. For example, you need to get to the airplane to be safer. Airport spaces such as crowded boarding areas, do not have great ventilation. Also, the filtrations systems on planes are not turned on during the boarding process.

SARS-CoV-2 is spread through aerosols and droplets. Filtration is great for floating aerosols, which can suspend in the air for hours. If the air is not filtering first, a passenger risks inhaling the SARS-CoV-2 aerosols in the air before filtering. Filtration is also not effective for larger droplets

Proximity to the index case (i.e., person originally infected before boarding) matters

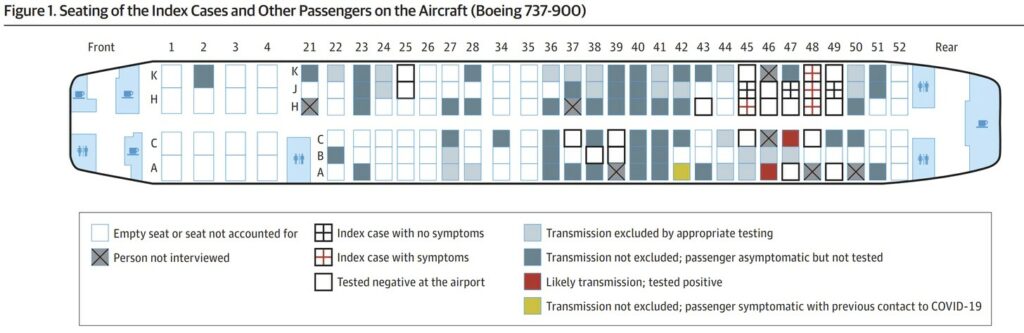

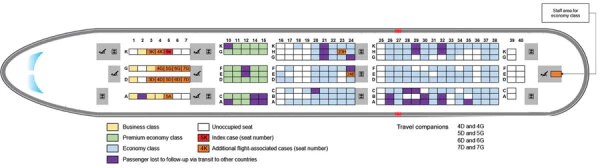

An extensive study traced 217 passengers and crew from a 10-hour flight from London → Vietnam in March 2020. Masks were not mandatory nor widely used. The index (infected) case was in business class and symptomatic with fever and cough. Sixteen cases were acquired in-flight (i.e., secondary cases). Twelve were in business class, equating to a 75% attack rate in business class. Two cases were in economy class and another case was a staff member.

Assessing another flight study from Israel → Germany in March 2020 with no masks. Secondary cases were two rows away from the index case.

Proximity is important and consistent with other viral outbreaks on planes. In a review of 14 studies, researchers found an overall influenza attack rate of 7.5%. Forty-two percent of the cases were sitting d within two rows of the index case. Similar findings were documented with SARS on a flight. Thirty-four percent were within 3 rows of the index case. As opposed to an 11% attack rate among persons seated elsewhere. There are many examples of secondary cases not in close proximity.

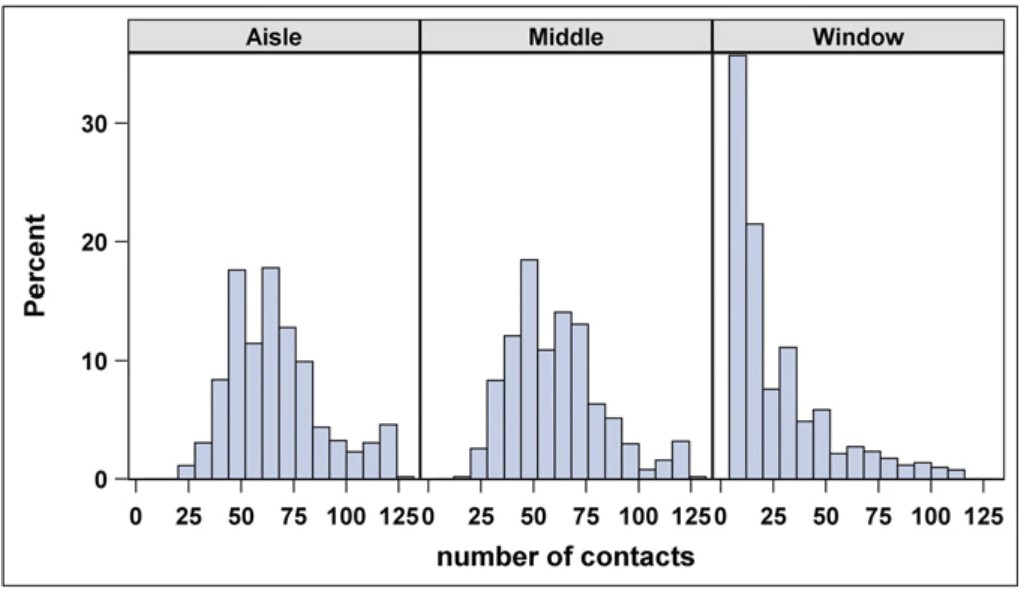

People move around a lot on planes

Nobody sits forever. Hence greater transmission or exposure. Pre-pandemic, one group traveled on 10 intercontinental flights to assess the behaviors and movements of people on planes and the impact on viral transmission. Of the 1,296 passengers observed, 38% left their seat once, 13% left twice, and 11% left more than two times. Eighty-four percent of passengers had a close contact with an individual seated beyond a 1-meter radius from them. People with the most contacts were sitting in the aisle compared to the window.

Percent of contacts by seating position across all flights. Figure Source: DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1711611115 found here

The assumption would be people in aisle seats have a higher risk of infection. A SARS-CoV-2 study found the opposite. The attack rate is higher for passengers in window seats (7 cases/28 passengers) and lower for people in non-window seats (4/83). The 7 window passengers never left their seat too. This factor makes other measures (masking) of prevention important.

Masks are Beneficial

Regardless of seating, evidence shows masks help to reduce transmission as shown by descriptive and modeling studies assessing the impact of masks on planes. Two public health reports assessed the transmission rates in the presence of rigid masking. The results affirmed low transmission with masking:

- The first flight study had 25 index cases and 2 secondary cases. One person was sitting next to a row with 5 index cases.

- On 5 Emirates Airlines with food service and passengers totaling more than 1500, no secondary cases were identified despite 58 index cases.

A 2021 modeling study was published with a few interesting findings.

- On a 2-hour flight with no masks, the average probability of infection was 2%. But if one sat next to an index case, the probability rose to 60%.

- On a 12-hour flight with no masks, the average probability of infection is 10% (or 1 in 10). If one sat next to an index case, the probability rose to 99%.

Besides wearing masks on planes, probabilities can vary with the wearing of high or low efficiency masks. Rick increases if not worn 100% of the time. The removal for meals increases risk. Passenger count and proximity to one another matters. The more the space, the less the risk.

Community spread

Transmission on a plane impacts those on the plane. The transported infections can spill over and drive community transmission, too. An international flight landed in Ireland in the summer of 2020. Despite low occupancy on the plane, 13 secondary cases occurred equating to a 9.8-17.8% attack rate. Outward transmission resulted in a spread to 59 cases in six of eight health regions in Ireland requiring national oversight.

The Bottom line or Reality

Planes have excellent filtration/ventilation systems. Vaccines are highly effective. However, no mitigation measure is perfect. Wear your mask while traveling, especially with increasing case trends. Mask wearing is not that big of an inconvenience for good health. There may be other health consequences resulting from contracting Covid. Consequences not widely known. Another topic for later.

Getting rid of the mandate feels like a real win for aviation as it eliminates the biggest source of conflict on planes over the past couple of years. Masking will still be common I think on planes and in airports and with the prior acceptance of cloth or procedure masks, I expect that the marginal impact is likely to be pretty low. From my last flight under the mandate (September 2021) it seemed that provided the passenger had anything that covered the mouth most of the time, it was all good with the crew. They were a bit strict verbally on takeoff, but that is a phase where they have to make a passenger-by-passenger review of lapbelts and seat backs. After that it was pretty much just do not make a scene of not wearing. Anyway, what I expect is that those with the good masks, worn correctly, will likely keep wearing for some time to come and those who ditch them basically are folks whose masking was ineffective in practice.

well, it was not clear to me that DOD based its conclusion an any actual study of transmission, but just concluded from the “fact” of ventilation and filtration that the probability of transmission was low.

this seems to be the way people think: take one “reason” or data and go directly to the conclusion you always wanted. note that the airplane ventilation only operates after takeoff. note also that busses and trains do not have the same levels of ventilation. hopefully your uber will let you open a window.

“The Premontion” by Michael Lewis gets into this kind of thinking a bit. “Uncontolled Spread” by Scott Gottlieb (former head of FDA) covers the same ground without the sensitivity to thought failure especially in bureaucracy. I may be being unfair to Gottlieb.

I recommend both books for those who want to learn something, But it takes some effort.

Since I can fly on my own schedule, I’ll aim for the sweet spot in the month or two after the peak when a lot of people will either be vaccinated or have acquired immunity the hard way. I’ll wear a mask.

Kalesburg

Flying Tuesday, Wednesday, or Thursday makes a difference in price, seats, and crowds. Mid month seems to work better too, if it works. I know some people like to go out late. I strive for after lunch on short (< 2 hours one way) flights. A little planning does make a difference.

there’s also the risk you might be loaded onto a bus at the airport; i don’t imagine buses have much of a ventilation and filtration system to speak of…

Recent experience: Flights on 26 and 28 April. Short (less than 3 hours) domestic flights in the USA between two busy airports. One of the two airports is a major hub for AA.

Overall, there was vanishingly small mask wearing. I doubt seriously it was 1%. I never took my mask off from the moment I exited my car.

Overall, masking isn’t common at all.