Debt and Taxes III

I don’t know if I should try to make my contributions to AngryBear a noahpinion sub substack or if I should put this over at my personal blog, but I am always stimulated by Noah’s posts . His most recent “No one knows how much the government can borrow” is on a topic I’ve mentioned here (and here also Brad all following Blanchard): How much should we worry about the huge and rapidly growing US national debt ?

Noah wrote that he doesn’t know and he doesn’t think anyone else does either. My comment is that Noah assumes things we don’t know. In particular, he assumes that we know something about how much the US Federal Government can borrow while paying record low interest rates. Noah write well, so it is hard to excerpt

“If the U.S. federal government keeps borrowing and borrowing and borrowing without limit, eventually foreigners and private companies and citizens are not going to want to buy all of those Treasuries. At that point the U.S. government can basically do one of two things:

It can offer higher interest rates, to make Treasuries more attractive, so that foreigners and U.S. private companies and citizens are willing to absorb larger amounts of debt.

It can have the Fed buy more of the Treasuries at a low interest rate.

But we have no way of knowing if we are anywhere close to the point where “foreigners and private companies and citizens” do not “want to buy all of those Treasuries”. In particular, the titanic gigantic issuance of Treasuries in 2020 did not drive interest rates significantly above record lows.

This is important as stressed in the linked posts here and elsewhere (including the AER) because if the treasury rates stay this low, the US Federal Government does not face a binding intertemporal budget constraint. The present value of future tax revenues would be infinite.

To me the question is how high does the US public debt have to go to drive Treasury interest rates above the rate of growth of GDP ? It was assumed that the super low rates of 2009-10-11- etc were a temporary effect of the great recession. It was also assumed that a few more Trillion in debt would have a large effect on the interest rates. Both assumptions sure look questionable now.

One of Blanchard’s many points is that Treasury rates have usually been lower than the rate of growth of GDP except for the period 1980-2000. It is possible that, except when Reagan and Volcker gang up, the US Federal Government usually has a slack intertemporal budget constraint.

Economists generally assume other wise, because we do maximization under constraint, and don’t like the idea that the constraint isn’t binding. We focus on finding optima and a slack buudget constraint can’t be optimal. But it is there in the data.

Here, I want to stress (as I have before) that statements about the US Federal intertemporal budget constraint are not entirely forecasts. The Treasury is selling 30 year inflation indexed bonds with a negative real yield. That rate is locked in for 30 years. Before worrying that investors might lose confidence in the Treasury if the debt increases, the Treasury can issue more long term bonds (and not short term notes and bills) and see the amount of long term bonds investors will buy at absurdly low interest rates. I mean this can be done quickly (both by the Treasury and by the Fed).

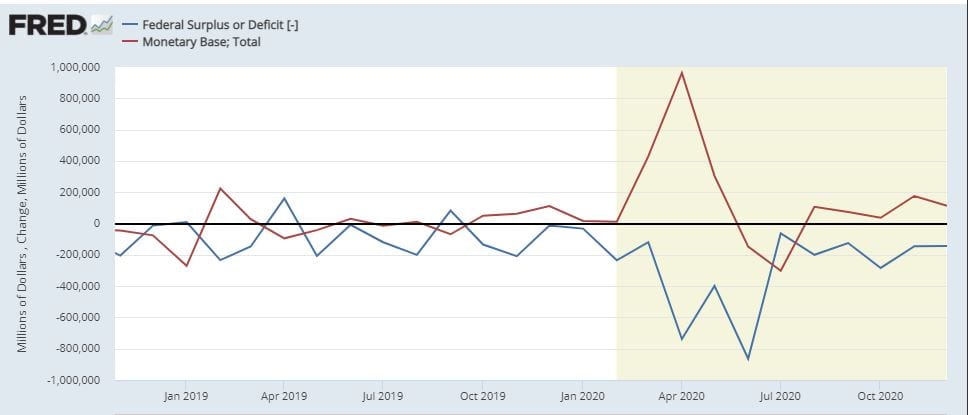

I have other comments. I think that Noah is influenced by trying to discuss economics with modern monetary theorists. They consider monetized debt and argue that the limit is unacceptable inflation. This is not all that happened in the USA in 2020. In June 2020 investors other than the Fed bought a Trillion more in Treasuries — there was a huge monthly deficit (huge for a yearly deficit) and the Fed sold assets (retired high powered money)

With that huge increase in the supply of treasuries, the price of a 30 year bond hit a record high (that is the yield was a record low).

The bottom line (quarterly not monthly) is that private investors were willing to buy more than an additional $ Trillion of Treasuries from Q1 2020 to Q3 2020 — this is not a state which is close to the point where it has to monetize its debt.

I’d say we have no idea how much the US Federal Government can borrow, but we can tell that we are nowhere near the limit.

It helps to look at it from an investor’s point of view. What are your options? You can buy shares of existing companies, real estate, government debt or pedigreed objects. In better times, I’d add productive assets, but most Americans have had flat or falling incomes for decades. Buying a monopoly position might make sense for the pricing power, but most people don’t have much money. If you sell one ownership asset, you are most likely going to just buy another, and there’s a good chance you’ll choose to buy government debt.

Robert:

Are you going to make Dan or myself work harder to C & P your articles from your blog over to Angry Bear. I enjoyed the read. I do not know everything about what you are saying but I get close enough to surmise where you are going with your thoughts.

But we have no way of knowing if we are anywhere close to the point where “foreigners and private companies and citizens” do not “want to buy all of those Treasuries”.

—]

Last time this happened, the Japanese bond buyers telephoned Powell, specified the rate needed was somewhat above 1%. Within a few days ten year rose by 25 basis points, causing our total interest payments on all debt to rise by 30%, or some 150 billion in the budget over the next six years.

It was widely reported on Bloomberg, widely commented and widely calculated, the day after the phone call.

Look up the reference yourself. But the key takeaway is that the bond market knows instantly when to raise rates. There is no uncertainty, there are regressive Fed taxes, but as long as Krugman agrees to tax poor people, we be fine. How long will progressives survive the horrid flat tax repression of poor people?

All it took was a non-committal comment from Janet Yellen to persuade Treasury traders there’s a chance the U.S. will finally expand maturities in the world’s biggest bond market beyond 30 years

The Treasury Department has pondered ultra-long bonds for years, but they’ve never been introduced in part because of resistance from Wall Street. But Yellen, President-elect Joe Biden’s pick for Treasury secretary, got people buzzing about them again by discussing the topic Tuesday during her Senate confirmation hearing. Markets responded, with traders selling 30-year bonds.

I just thought that it might be pertinent to point out that you might want to monetarize the debt even if you don’t have to. In fact in the book that everybody should read “Between Debt and the Devil” it was pointed out that even Friedman expected that some of the debt would be monetarized in his original concept of monetarism. The idea that debt should not be monetarized is a rule with no good theoretical base. It is based on absurd slippery slope arguments that can be easily overcome with rule based controls.

Once we beat the pandemic and get private spending back on track then it will all be fine. Consumers buying Chinese made goods force China to buy dollar denominated bonds to keep the Yuan Renminbi from rising against the US dollar. The FIRE sector buys the rest as long as Treasuries stay safe. Only default can kill the fun.

Meanwhile during the pandemic, then what pressure could be placed on the Fed to limit its purchase of bonds added to its balance sheet given that the world expects the US economy to take off like a rocket once the economic impact of the pandemic has passed? If the trading price of US Treasuries fall then all of the present holders of US treasuries take a hit on their own balance sheets.

So then the question is more whether the financial world views the actions of the Federal Reserve necessary to stabilize the US economy and by the importance of the dollar to foreign reserves and trading also the global economy or whether the financial world views the actions of the Federal Reserve reckless and destabilizing to the US economy and the global economy as well. The US central bank has the exorbitant privilege of being the lender of last resort for the global economy.

Another good question is whether debt scolds really believe that private banking usury would be better served by a central bank that did not act responsibly to preserve global financial system liquidity? Or maybe they want a federal government that does not pay its bills?

Bankers (literally) talked Wilson into WWII at Versailles. Then bankers (figuratively) talked FDR into eternal fiscal deficits at Bretton Woods. Then it took Nixon to release the Kraken, although Nixon had already been dicked by Bretton Woods thereby leaving him no better choice than to end convertibility. If now bankers do not want to sleep in the bed that their kind made for themselves, then it is still not too late to nationalize the entire FIRE sector. Not that it would ever be done, but it does put things in perspective.

At Bretton Woods it was literally bankers also, but only figuratively FDR. FDR had trusted Morgenthau and White, which turned out to be a classical choice of short term private banking interests over long term sovereign economic interests, a matter of visionary blindness.

focus on debt is too narrow.

the question is not “is some level of debt good or bad, will the market sort it out.” the question is what are we spending the money on…useful or not useful. and the answer to debt is, if we think it is too high, raise taxes to pay for current spending, instead we get every year R’s: “we need to cut taxes to stimulate the economy. but we need to cut spending on the needs of the people because of the deficit.” i have no doubt the bankers and the bond market can go a long way to making playing games with the debt a paying proposition for “us” and even for the rest of us. but we need to see that we are playing the same game, arguing the same arguments, and the poor are still shamefully poor and the rich are still dangerously rich.

adds on AB block the spaces for reading, commenting or posting, and won’t go away when you ask them can’t we fix even that?

Investor returns in the short run are higher if liquidity is regulated and risk is insured, but economic returns are higher in the long run if liquidity is insured and risk is regulated.

Ron

pretty cryptic. would you care to expand on your argument for those of us who don’t understand. in the unlikely event that the ignorant masses might know, and knowing understand, and turn and be saved.

Coberly,

[If I had to guess which of my comments that you found cryptic (and I do have to guess), then it would be the following which I will then explain the meaning.]

***************

“Investor returns in the short run are higher if liquidity is regulated and risk is insured, but economic returns are higher in the long run if liquidity is insured and risk is regulated.”

********************

[Investors want restricted liquidity rather than accommodations from the Fed to increase the money supply and lower interest rates in response to an economic downturn and they also want free reign to invest in derivatives to bet on futures and particularly protect their financial assets from downsides. That makes them more money until they crash the financial system and put the US economy into a depression. Investors do not care though because they have more savings than debt unlike ordinary working people and investors do not have jobs. Also investors will still be rich even if less rich and depression causes a fire sale on what will be valuable assets later after economic recovery.

So, the economy is better off if investors do not get everything that they want and the central bank accommodates the economy instead of wealthy investors. And we need more risk limiting financial regulation instead of less as investors would prefer. Credit default swaps were just plain illegal for a long time, then they were set free to make the 2008 financial crisis the biggest since the Great Depression.]

How about this for an exorbitant privilege? The twin (trade and fiscal) deficits of the US economy are both caused and financed by the Triffin dilemma.

Dunno. Was “Bankers (literally) talked Wilson into WWII at Versailles” cryptic? The long story was that US bankers demanded Wilson have the French and British repay their war debts to the US, which Wilson in turn demanded at Versailles. In return then Wilson agreed to the reparations from Germany that the French and British argued would be necessary in order for them to repay their war debts to the US. John Maynard Keynes then wrote the The Economic Consequences of the Peace, which explained how this reparation and debt repayment arrangement would cause the financial collapse of Germany, which in turn would have serious economic and political consequences throughout Europe and the world.

Above I underlined The Economic Consequences of the Peace and it dropped from post.

Did it again, so my fat fingers are innocent.

Far from my area of expertise, but I have been increasingly drawn to the notion from an historical perspective, that the debt just doesn’t matter. At all. That as mankind has begun to learn how to really use fiat money (it has been an on the job trial and error process) it turns out that we actually have all the tools necessary to control our economies and the real problems are political. A lack of imagination and a reluctance to use the tools we understand and to discover the tools that we have yet to fully develop. The luddites rail against “fiat money” because it is untethered to a physical anchor. But that is precisely its primary strength. All of the degrees of freedom exist within a system where the government prints it own currency and has adequate regulatory power to control the money supply, inflation and interest rates. You may have to periodically monetize the debt, mint the platinum coin, whatever and reset the system but there is absolutely no reason to fear some sort of external ultimate limit outside of the ability to control the basic parameters. We as a species are still learning about this. It hasn’t been all that long. But it seems most of the pieces are there waiting to be implemented. And certainly during a national crisis, worrying about the debt is probably one of the dumbest god damn things imaginable.

Sovereign debt in and of itself in that sovereign’s own currency unencumbered by that cross of gold or any other tangible asset peg is always a manageable problem in and of itself. But in economics nothing is ever in and of itself perpetually. Any deflationary pressure whether falling working age population or falling productivity or just a steep cost curve for energy resources, then the resulting deflationary pressure can nail debt to its own cross.

Japan had almost climbed out of its deflationary spiral when it was thrown back into it by the pandemic.

IOW, inflation and rising interest rates are definitely not the worst possible outcome from increasing sovereign debt. Nope, that would be deflation. It requires another condition, falling GDP for any reason whatsoever. But deflation sucks.

Ron

your guess about my “cryptic” was right. you know more about money and debt than i do. problem for me isto learn enough to understand what you are telling us.

have been too busy today with SS issue to really follow all this. should get back to it tonight.

Coberly,

No problem. I will check back every day in case you have any further questions. All those years at Ev gave me a solid foundation in monetary macro. When socialist Owen Paine and monetarist Mark Sadowski engaged in macro policy Internet flame wars then I read everything, did background research on anything that escaped me, and I learned.

Ron

thanks. no need to check back. i will ask questions as we go. i probably would need to do what you did: study. remains to be seen if i have the time.

Coberly,

Okey-dokey then.