Need proof changes at the USPS are slowing down the mail?

Save the Post Office is edited and administered by Steve Hutkins, a literature professor who teaches “place studies” at the Gallatin School of New York University. Prof. Hutkins (Steve) is the author of this commentary. (Angry Bear Blog has had a long relationship with both authors Steve Hutkins and Mark Jamison both of whom author the “Save The Post Office Blog.”)

Everyone knows the mail has been slowing down. News reports are filled with stories from postal workers and customers about delays. E-bay sellers are complaining about shipping problems with the USPS, and many say they have been switching over to private carriers. Talking Points Memo has an ongoing column based on reports from the field. Ask anyone, and they can tell you about problems they’ve had getting a package or an important letter.

For a while, it seemed that the pandemic was causing these problems, and there’s no question that the surge in packages was a challenge for the Postal Service to keep up with.

But then came Mr. DeJoy, the new Postmaster General.

Within weeks of his taking office in mid-June, changes were being made at processing plants and post offices that appeared to be causing delays not just in parcel delivery but for letters and flats as well. In a memo to postal employees, DeJoy admitted it: “Unfortunately, this transformative initiative has had unintended consequences that impacted our overall service levels.”

These “service levels,” aka “service performance,” refer to the percentage of the mail that is delivered on time, i.e., within the “service standard” for each type of mail. For First Class mail, the standard is 2 days for local mail and 3 to 5 days for regional & national mail. Marketing Mail has a service standard of 3 to 10 days. Typically, about 85 to 95 percent of the mail is on time, although in some cases the performance scores can be lower and the delays can go on for several days.

The Postal Service shares quarterly service performance reports on its website and with the Postal Regulatory Commission (PRC), which posts them here. The most recent reports cover the third quarter, April 1 – June 30. This table based on those reports compares the third quarter performance for single-piece First Class mail in 2019 and 2020. It shows declines in near every district. In some, the drop was striking. Nationally, performance on 2-day mail dropped from 93.9 percent to 92.4; for 3-5 day mail, from 86.5 to 81.4 percent. Presumably, these declines were due to the pandemic.

As for what happened after June 30, the Postal Service hasn’t provided any details about the delays. It knows, of course, exactly how bad the delays are and where they are occurring, as reported internally in weekly performance reports similar to the quarterly reports. But these weekly reports are not shared with the PRC or the public.

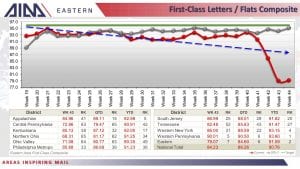

One can, however, get a good sense of what’s in those weekly reports by looking at some charts that appear in two USPS presentations given earlier this month that were published on PostalPro, a website where the USPS shares information with its business customers.

As seen in the following charts show the on-time performance for the Pacific and Eastern Areas on a weekly basis for the past few months. The charts prove that it’s not your imagination. The mail has clearly been slowing down since the beginning of July — dramatically.

Eastern This first chart shows the service performance for a composite of all First Class mail (letters and flats, single piece and presorted). The target for this class (the green line) is a score of about 96 percent. Actual performance scores generally fall a couple of points below that, as shown in the gray line for the same period last year.

Eastern This first chart shows the service performance for a composite of all First Class mail (letters and flats, single piece and presorted). The target for this class (the green line) is a score of about 96 percent. Actual performance scores generally fall a couple of points below that, as shown in the gray line for the same period last year.

This year there was a precipitous drop in on-time performance, starting at the beginning of July (week 40 of the fiscal year, which began on Oct. 1, 2019) to about 78 percent. The scores for some individual districts are even lower, like Northern Ohio, with an on-time score of 68 percent. These are obviously extremely poor scores and a clear indication of the extent of the delays.

Here’s the chart for First Class mail in the Pacific Area. It tells the same story: a sharp decline at the beginning of July.

Pacific Now let’s look at Marketing Mail in both Eastern and Pacific areas. As with First Class, the scores plummet at the beginning of July, perhaps a week sooner.

Pacific Now let’s look at Marketing Mail in both Eastern and Pacific areas. As with First Class, the scores plummet at the beginning of July, perhaps a week sooner.

Marketing Mail is generally advertising mail, much of it not especially time sensitive (don’t tell that to the mailers). This is also the class, however, used for a lot of Election Mail, including ballot applications and sometimes also ballots sent to voters. A USPS presentation on Election Mail in 2016 showed that there were about 300,000 pieces of Election Mail; about 43,000 went First Class, while 257,000 went as Marketing Mail.

As Ruth Goldway notes in an op-ed in the August 18th New York Times, “The Postal Service has a history of providing extra care and attention to election-related mail, on the level of first-class mail.” But recently the Postal Service has been telling election officials that Election Mail will be treated as the class it was sent. Marketing Mail can take as long as 15 days. “This is not acceptable,” writes Goldway.

This year the volume of Election Mail will soar, perhaps to 600,000 pieces, with about 500,000 pieces sent as Marketing Mail. If this mail were given first class treatment, such that the Postal Service covered the difference in its own processing and delivery costs (about 30 cents per piece), it would cost the agency about $150 million. If the Postal Service can’t afford to do that, Congress should appropriate the money.

In the meantime, we need to know more about the scope and severity of the delays. Congress should immediately ask the Postal Service to provide the weekly performance reports for all areas and districts, and if they’re not forthcoming, journalists should file FOIA requests for them. There’s also something called Customer Service Daily Reporting System (CDSRS), a formal delayed mail-reporting tool that provides information to management on mail and operational exception situations. The system generates reports that could also be helpful in understanding the scope and severity of the delays. Congress should ask for them as well.

—Steve Hutkins, ed.

No proof needed, their financial statement says it all.

All the high valued shipments are going with on demand delivery. So UPS, FedEx, and many local delivery companies do not have the burden of daily deliveries. It is a losing situation, it is not really a left-right thing, it is a Constitutional thing.

Suggest we are all stuck, left, right,up,down,middle. if it is in the Constitution is is hard to avoid the losses. We have no choice,, tax ourselves to cover the losses.

anonymous:

The USPS was never meant to be a profit-maker. As you say. it is mentioned in the Constitution. However as what a retired postmaster by the name of Mark Jamison will say:

Asking the Wrong Questions

“In 2015 I (Mark) wrote a piece titled “When Titans Collide.” UPS petitions the PRC to change USPS costing methodologies.” The piece examined a year long attempt to gerrymander postal costing and pricing systems in ways that best served those in the mailing and package delivery industries. Some of the players have changed over the years as the mail mix has changed, but the goal remains the same – find a way to defenestrate the Postal Service.

The piece looked at the issues that were at the crux of Mr. Trump’s complaint – the Postal Service wasn’t charging enough and it was making “bad deals.” I looked in detail at some of the costing and pricing methods and tried to engage those specific arguments. But the heart of the matter was that the Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act, the 2006 law that in many ways governs the operation of the Postal Service, had set up an impossible and counterproductive environment that failed to recognize the value of the postal network as an essential national infrastructure.”

anonymous, I am happy to expound upon the USPS which I value as a service we would be paying much more for if it were in the hands of FedEx, UPS, or Amazon. It was never meant to be a profit maker and being that it delivers where the former three would never go or would charge multiple times more, it does lose money doing so. However, it is an essential part of the US infrastructure serving the citizens of the United States globally.

The issue to what you are really asking about is the “Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act.” Under the PAEA, the Postal Service was required to pay $5.5 billion a year, for ten years, into a fund to cover the costs of retiree health care for decades down the road. In the beginning, they met the goals of paying it until Wall Street decided to blowup the economy by not having the reserves in place to backup the gambling debts they incurred from CDS, naked CDS, tranched CDOs, etc. to which main street paid for and USPS suffered a loss of business as the country recouped from their thievery. Senator Susan Collins was a prime instigator of the PAEA.

I have attached two links to this comment as written by retired Postmaster Mark Jamison. Take a few moments and read their lengthy analysis. You will be smarter on the topic than ,most people who peruse Angry Bear posts then.