Rep Jayapal and Sen Sanders Have Introduced Medicare For All Bills: Part 2

Part 2 discusses why we must have the government issue payments to hospitals, clinics, etc. and also set the budgets for hospitals and this is how they are paid rather than billing multiple insurers and also patients. There is also only one payer. The later part is what I have been pounding on repeatedly. Forget prices and work with cost data. It is then we have a much clearer picture of the costs of healthcare and we can begin to control prices.

Rep Jayapal and Sen Sanders Have Introduced Medicare For All Bills: One Is a Lot Better Than the Other, Healthcare for All Minnesota, Kip Sullivan, May 8, 2019

What is an ACO and why is it a defect?

Congress included in the Affordable Care Act of 2010 (aka Obamacare) a section (Section 3022) requiring CMS to establish an ACO program within the traditional FFS Medicare program. It is not clear why Congress chose to use ACOs. Congress was warned in 2008 by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) that ACOs would not save money for Medicare. The simplest way to describe ACOs is to say they are HMOs in training. Like HMOs, they are corporations that own or contract with chains of hospitals and clinics; they have the equivalent of enrollees; they attempt to keep their “enrollees” from seeking care outside their networks; they bear insurance risk (that is, they are paid on a per-enrollee basis and in exchange are obligated to provide medically necessary services to their enrollees); and because they are risk-bearing organizations, they generate overhead costs similar to those created by traditional insurance companies.

More on ACOs and the absence of Single Payer budgets past the leap

In fact, precisely because ACOs resemble insurance companies, nearly half of them already have contracts with insurance companies to help them carry out insurance-related tasks. The largest insurance companies – Aetna, Humana, and United Healthcare, for example – are already deeply embedded in the ACO industry.

The only significant differences between ACOs and HMOs are (1) ACO “enrollees” are assigned to ACOs (usually without their knowledge) whereas HMO enrollees choose to enroll, and (2) HMOs bear all insurance risk while ACOs split the risk of loss or savings with another insurer (in Medicare’s case, risk is shared with the Medicare program). [5] Both of these differences are being eroded. Many ACOs are saying they should be allowed to enroll people so they can restrict enrollee use of out-of-ACO providers, and some influential ACO proponents are proposing that ACOs be paid premiums so they can absorb total losses and keep total profits.

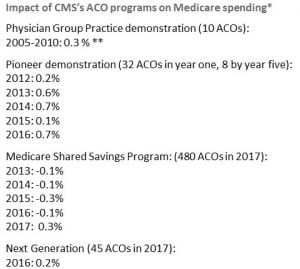

One other important similarity between ACOs and HMOs: ACOs have failed to cut Medicare’s costs, just as the CBO predicted. [6]

Defect 2: Absence of hospital budgets

I mentioned above that an American single-payer system could reduce total spending by 10 to 15 percent just by eliminating excess administrative costs. A large portion of that savings would come in the form of reduced administrative costs for hospitals (the rest comes from reduced administrative costs in the insurer and physician sectors). Hospitals enjoy lower overhead costs in single-payer systems for two reasons:

First, they are paid with annual budgets, not on a per-patient or per-procedure basis, which means they don’t have to keep track of every pill and x-ray for every patient.

Second, for the covered services, they deal with only one payer, not hundreds, each with their own hoops to jump through.

Unlike Representative Jayapal’s bill, Senator Sanders’ bill does not authorize hospital budgets. There is a reason for that: It is not possible to set premiums for 1,000 or 2,000 ACOs, which consist of hospital-clinic chains with an insurance company or department plopped on top of it, and at the same time set budgets for each of the nation’s 5,500 hospitals. One has to choose one or the other: Premium payments for ACOs, or budgets for hospitals. Sanders chose ACOs. Jayapal chose hospital budgets.

But by sacrificing hospital budgets in order to make room for ACOs, Sanders guaranteed his bill cannot reduce hospital administrative costs much or at all. Research indicates US hospitals spend 25 percent of their revenues on administration, thanks to the complexity of our multiple-payer system, while hospitals in single-payer systems that use hospital budgets devote half as much to administrative costs.

We must take into account as well the additional administrative costs for doctors in Sanders’ proposed multiple-ACO system. Like hospitals, they will have to determine, for each patient, which ACO a patient belongs to and send the bill to the right one.

Cost containment must accompany or precede universal coverage

If you happen to believe that some fine day America will find the political will to insure everyone at the high price at which health care is sold today, then you should ignore what I have said here. You should feel free to endorse any legislation that proposes to raise taxes high enough, or levy compulsory premium payments high enough, to achieve universal coverage. No need to worry about whether a bill that purports to achieve universal coverage can reduce costs. No need to ask yourself why US per capita health care costs are double those of the rest of the industrialized world. The answer is: Primarily because of our high prices, and the excessive administrative costs generated by our multiple-payer system that drive prices up, and not “overuse” of medical services.

But if you think, as I do, that cost containment must accompany or precede universal coverage, then you must support legislation that includes evidence-based, cost containment provisions, such as Representative Jayapal’s bill. I do not believe our nation will find the political will to pay for universal coverage at today’s prices. Moreover, even if the political will were there, I don’t believe it is ethical to pay more to solve any social problem than we have to. Our society has numerous other demands on our resources, ranging from hunger to crumbling infrastructure to climate change. Paying more than necessary to ensure all Americans means we will have fewer resources left with which to address other problems.

Representative Jayapal’s bill, HR 1384, meets the definition of a single-payer bill as originally outlined in PNHP’s 1989 article and as most experts define the term. It contains the four elements of a single-payer system:

- It relies on one payer (HHS, not multiple payers called ACOs) to pay hospitals and doctors directly,

- it authorizes budgets for hospitals,

- it establishes fee schedules for doctors,

- and it has price ceilings on prescription drugs.

Senator Sanders’ bill contains two of those four elements – fee schedules for doctors and limits on drug prices. That’s a good start. He should add the other two. He should get rid of Section 611(b), the section that authorizes ACOs, and thereby ensure HHS is the single payer. And he should add a section authorizing HHS to negotiate budgets with each of the nation’s hospitals.

(Kip Sullivan is a member of the Health Care for All Minnesota Advisory Board and of the Minnesota chapter of Physicians for a National Health Program.)

All of this is all well and good, but the American people, despite years of advocacy by Bernie Sanders for single payer under the Medicare-for-All label, remain unconvinced that on net it would be a good deal. It is going to take years of relentless education to convince Americans that they will pay less and otherwise be better off under the single payer system. If Congress becomes for it (because the solid majority of Americans have been persuaded to support it), it will pass and any one of the Democratic candidates would be happy to sign it.

The main objections of Biden, Klobuchar and Buttigieg have nothing to do with the merits; it’s strictly, as it should be, about what will sell in the 2020 election. With the dramatic difference in poll results between including a Medicare buy-in as a public option highly favorable) and single payer with private insurance eliminated (about 50-50 leaning favorable), strongly suggests that it will be a huge negative in Novembere.

Urban:

Did you learn anything from this?

And no, it will not take years for them to change their minds. I would say 2 years at the most. By that time Hospitals will have increased pricing again and still be the leading cause as to why commercial healthcare insurance premiums, deductibles, and copays keep increasing. Pharma will keep increasing their prices at 2 to 4 times CPI. It will not be long before all of you start to whine and stomp your feet.

Did you know I wrote a piece on the conversion from commercial healthcare insurance to Medicare for All using Kocher and Berwick which addresses what you stated? Probably not, otherwise you would not have said that to me. The puzzling part is the bravado you display and you know little about the topic. This is why I take the time to write on the topic so you and the others do have some knowledge of where we need to go. direction of sorts.

The post had nothing to do with Biden and the others.

We don’t have two years. With the Presidency and both house of Congress, the work can begin and maybe within the first term enough minds will have been changed. But Bernie’s had over four years, and public reception has barely budged. So what is the plan to change public opinion? It needs to be massive and highly sophisticated because the subject is so complex.

Just for starters, what is the plan for satisfying (or silencing) the many tens or hundreds of thousands of people in the insurance business who fear they will lose their jobs with a deliberate and inevitable relatively abrupt change that is intended to cost them their jobs? Without a solid plan, they will become a potent anti-change lobbying force in every state that few if any senators will be able to resist. An evolutionary process based on a public option over the course of years taking a dominant position in the marketplace does not seem to spark the same level of fear. Advocates could also mollify such fears if, rather than, as Sanders has done, issuing draconian pronouncements completely eliminating any private insurance whatsoever, they expressly allow for private insurance to fill in gaps in public coverage and participate in the equivalent of the Medicare Advantage program.

Sanders at the last debate suggested re-training programs could help take care of those losing their jobs. I don’t recall him praising programs like that intended as a PR band-aid to make trade deals more palatable?

Your points mostly look valid, but at this point the Medicare-for-All debate is not about the merits. Only the politics matter. If talking about it will win more votes than will be lost, fine. But if not, and it looks at this point as if it will be not, then the candidates should shut up about it. Look at how Warren tanked in the polls when she went all-in with Bernie on Medicare-for-All. Up to that point, she was the non-Bernie progressive and could draw from both the left and the uncommitted. The decision to focus solely on the progressive wing detracted from her electability argument, since it is probably true that a candidate perceived to be a socialist probably cannot win even against Trump.

Urban:

Did you google Kocher and Berwick or did you use the search function at AB for Kocher? You might have found what you wanted. Did you follow the link to Kip who is leading the effort on Single Payer in Minnesota which might be the best place to start . . . state. There is no plan which will get this past the healthcare industry, the healthcare insurance industry, and the Republicans. They will not acquiesce as there is too much much money in this. The move will be draconian.

Insurance is in the service industry, a growing segment of the economy. They will find jobs which are service related far easier than those whose skills were manufacturing. MA plans owe the gov $30 billion in over billing seniors over a 3 year period and they are fighting back to not pay it. I wonder why CMS is not moving too fast on this. It is the same we have today with healthcare and insurance. public option with commercial healthcare not give you what you want. It still involves commercial insurance which will charge 15-20% on top of the costs. It will still involve high admin costs for doctors, clinics, and hospitals due to the numbers of insurance companies.

Again, I am not writing about or promoting Bernie’s version. Did you note the defects? I am offering information about Single Payer.

“It is going to take years of relentless education to convince Americans that they will pay less and otherwise be better off under the single payer system.” I said it would take two years more and I would add of “blaming the ACA for all the unwarranted price increases the healthcare industry and the healthcare insurance industry imposed.” Did you even know, Congress struck the exclusivity out of the NAFTA bill, applauded themselves, and then restored a longer (12 years) exclusivity version of it in the House Budget bill. And this comes on top of most drugs being able to recoup risk adjusted R&D costs, etc. in a median 3 to 5 years.

Because most of the people are tweeting away and believe whoever promises, without looking for the facts; they expect it to be dropped in their laps. I am here to provide the information so you can learn and apply it. I do fight with the biggies too. Ask Dan if you do not believe me.

Comparing insurance industry workers at risk of losing their jobs to manufacturing workers (many of whom still do not have jobs, and most of whom do not have comparable jobs), even as a contrast, is not exactly the way to win those hearts and minds.

You just are not getting the politics of this. You have to think not only about what is best substantively, but what kinds of arguments can be made in simple words, how believable those arguments are to the average, suspicious-of-government American, how vulnerable the argument is to counter-attack by any of the many, many people who have a vested interest in the private-industry based system we have. As of now, the majority of Americans have no trust that the additional taxes they would have to pay would be less than the premiums and other costs they pay now (which I do believe).

We have to remember that the public is not in a revolutionary mood, even about health insurance, because for the overwhelming majority their claims are just routinely paid. The system may be creaking and frightfully too expensive, and they are certainly open to fixing some obvious flaws, but for most claimants it does work.

“Did you google Kocher and Berwick or did you use the search function at AB for Kocher? You might have found what you wanted. Did you follow the link to Kip who is leading the effort on Single Payer in Minnesota which might be the best place to start . . . state. There is no plan which will get this past the healthcare industry, the healthcare insurance industry, and the Republicans. They will not acquiesce as there is too much money in this. The move will be draconian. “

If not, you are not reading and paying attention. I am not going to tell you what it is. You have to do some research yourself. And “no,” you are not understanding the politics of it. A public option involving commercial healthcare akin to Medicare Advantage or a Public Option will fail. The costs of which are 15 to 20% for administration and another 20% coming from Hospital administration.

Furthermore, this entire post was meant to educate “YOU” and others on what Single Payer is which you still do NOT know and are attempting to make the post into something it is not. Other places will not allow you to hijack a post or comment section and I will not either even though we are far more liberal in views.

Perhaps you can write about an alternative to Single Payer and I would be willing to post it for you. I would urge you to read Kocher and Berwick first though.

OK, I just did. What is their opening paragraph?

“While it is fascinating to think about “Medicare for All” (and one of us strongly favors it), it is unlikely that the United States will move quickly to fully publicly financed health insurance when Congress next considers health policy after the 2020 presidential election. Despite its theoretical advantages, passage of Medicare for All would require a massive political battle to make feasible the shift from private to public funding, to develop enough public trust to expand an entitlement program for all Americans, and to mitigate the disruption (for many) of substituting public insurance for familiar, existing health insurance policies. That will take time. Fortunately, even while the Medicare for All saga rolls out, much can be done in the meantime that is politically plausible to augment and improve the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and make health care work better for all Americans.”

“Theoretical advantages.” “Massive political battle.” “Public trust.” “Entitlement program.” “Disruption.” How does this not support exactly what I have been saying?

Urban:

I asked you several times to read Kocher and Berwick and I also told you this post was to explain Single Payer several times.

You are stating I am not in alignment, when I really am. I stated the goal was Single Payer (several times) and this post was to explain single pay (several times). I also suggested there is a way to get there (in my comments) as stated in Kocher and Berwick. The first step is to explain Single Payer and who has true Single Payer which I did using Kip’s information. He knows single payer and I agree he knows. The next step is how do we get there. Kocher and Berwick gives a brief passage detail to single payer. Berwick is Dr. Donald Berwick the former director of Medicare and Medicaid under Obama which a Repub legislature refused to confirm. This is what he said when he left:

Kocher and Berwick have a path which Kip (I am certain) and I agree with if we are going to Single Payer. Much can be done in the interim, such as attack costs and exclusivity (these are the issues giving cause to the rising prices of healthcare insurance, deductibles, copays, rise billing, etc.). These issues I have talked about repeatedly time and time again. Even so, none of the actions touch the admin costs associated with insurance or hospitals in working with multiple billing companies, the waste in care, over billing by MA plans, PBM costs, and other costly and unnecessary expenses.

You will have to excuse me as I am tired. Search anything on AB in Search under healthcare and there is a wealth of information I have documented and written which is going into the Library of Congress. Use it . . . I am not done yet. (Edited)