“Are Robots Stealing Your Job?” is the Wrong Question

Andrew Yang says, “Yes, Robots Are Stealing Your Job” in an op-ed at the New York Times. Paul Krugman thinks they’re not and advises, “Democrats, Avoid the Robot Rabbit Hole.” This is, of course, a classic case of asking the wrong question.

The real question is: will robots burn down your house and kill your grandchildren? Let’s imagine that all those self-driving trucks and the computers needed to guide them will run on electricity generated by wind turbines and solar panels. Will the robots in the truck factories and the robots in the computer factories also run on wind and sunshine? How about the robots in the wind turbine factories and the solar panel factories and so one ad infinitum? I know an old lady who swallowed a fly…

Let’s assume that it is feasible to phase out all current fossil fuel consumption by 2050 and replace it with renewable, zero-carbon energy. Does that mean it is equally feasible to provide the additional energy needed to run all those job-stealing robots? Or to put the question in proper context, would it be feasible to do it without an uncorruptable, omniscient global central planning authority?

The hitch in all this robot speculation is a little paradox known as Jevons paradox conjoined at the hip, so to speak, with it’s counterpart, “Say’s Law.” The former paradox says that greater fuel efficiency leads to more fuel consumption, the latter paradox tells us that labor-saving machines create more jobs than they destroy. Here are two inseparable positive feedback loops that together generate an incongruous outcome. “Yes the planet got destroyed. But for a beautiful moment in time we created a lot of value for shareholders.” Or lots of jobs, jobs, jobs. Or a monthly $1,000 payment to every adult “so that we can build a trickle-up economy,” Choose your poison.

There is, they say, “a certain quantity of work to be done.” Who says that? Good question. In the beginning, it was the political economists — even proto political economists — who said it. But around 1870 economists realized that the maxim conflicted with other things they had in mind so instead of professing it they began to condemn it and to attribute the idea to others — to Luddites, Malthusians or Lump-of-Laborers. The idea that a people could always do more work was just too great a temptation. In principle, the amount of work that could be done is infinite! The robots will not replace us! The robots will not replace us!

What this job-stealing robot debate is really all about is an economics version of theodicy. “Why does evil exist if God, the creator, is omnipotent, omniscient and good?” This theological question is echoed in the puzzle about poverty in the midst of plenty and in Mandeville’s “Fable of the Bees,” where private vices promote public virtues. If it seems like robots are stealing your job, have faith, all is for some ultimate purpose in this best of all possible worlds, as Candide’s tutor Dr. Pangloss would assure him.

Taking the Panglossian philosophy into account, it becomes clear that both Andrew Yang and Paul Krugman are on the same page. They are just reading different paragraphs. Although they disagree on what the solution is, they agree that there is a solution and it doesn’t really require a fundamental change in the way we think about limits to the “certain quantity of work to be done.”

There isn’t a certain amount of work, but there is a certain amount of energy which can produce work, and therefore potential for work. Earth is an exothermic system, and there are ways to increase the amount of energy that can be captured (space based solar, up to the limit of Dyson sphere, if you had enough material to construct it), but they become increasingly expensive.

The real question, which ties into the omniscience one, is how long will robots be what we currently think of them as? To be sustainable, eventually robots become organic systems that are forced into labor: constructed slaves.

Interesting incremental game about paperclip building robots destroying the universe: https://www.decisionproblem.com/paperclips/index2.html

Robots are not stealing jobs. Anyone who shops at Walmart, Tractor Supply, Harbor Freight, Dollar Stores, Lowes, Home Depot or virtually any major retailer knows that all of their goods are manufactured in China, Vietnam, Bangladesh or similar countries. It is only because of low wages

Low Overhead

Once again, it doesn’t mattered where they are manufactured. They create little in the way of jobs. That is not the point. You have to create jobs yourselves in general. That requires will.

Sandwichman,

I’d be interested in your thoughts on this:

Big fan of Baker, and I agree that the job losses from 2000 to 2010 were mostly due to trade. But some of his numbers seem to ignore something.

“The New York Times ran a column by Andrew Yang, one of the candidates for the Democratic presidential nomination. Mr. Yang used the piece to repeat his claim that automation is leading to massive job loss.

His one piece of evidence is a study that purports to find that 88 percent of job loss between 2000 and 2010 was due to automation. As I and others have pointed out, it is difficult to take this claim seriously. This was a period in which the trade deficit exploded from 3.0 percent of GDP to almost 6.0 percent of GDP. This would seem to be the more obvious source of job loss.

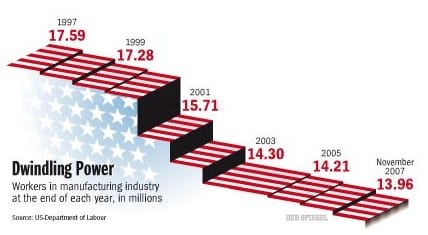

It is also worth noting that we lost very few manufacturing jobs between 1970 and 2000. Since 2010 we gained a small number of manufacturing jobs. So anyone wanting to push the automation job loss story has to believe that for some reason automation didn’t cause substantial job loss from 1970 and 2000 and then stopped causing job loss in 2010.

I suppose Andrew Yang can believe something like this, but I don’t know too many other people who could consider this story credible.”

http://cepr.net/blogs/beat-the-press/making-andrew-yang-smarter?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+beat_the_press+%28Beat+the+Press%29

It is true that the number of manufacturing workers stayed roughly even from 1970 to 2000, yet what is ignored is that the percent of manufacturing workers in the population declined by half during that period.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/USAPEFANA

Further, he seems to ignore the manufacturing output during that period. I cannot seem to get Fred to give me a history of such from 1970, but there is this regarding the critical period(according to Baker) of 2000 to 2010.

We know the decline in the number of workers during that period, but baker seems to ignore manufacturing output.

“Manufacturing jobs in the United States have declined considerably over the past several decades, even as manufacturing output – the value of goods and products manufactured in the U.S. – has grown strongly. But while most Americans are aware of the decline in employment, relatively few know about the increase in output, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

Four of every five Americans (81%) know that the total number of manufacturing jobs in the U.S. has decreased over the past three decades, according to the survey of 4,135 adults from Pew Research Center’s nationally representative American Trends Panel. But just 35% know that the nation’s manufacturing output has risen over the same time span, versus 47% who say output has decreased and 17% who say it’s stayed about the same. Only 26% of those surveyed got both questions right.”

https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/07/25/most-americans-unaware-that-as-u-s-manufacturing-jobs-have-disappeared-output-has-grown/

In that link there is a chart that shows output increased about 25% from 2000 to 2008(and the onset of the recession) and then came back down to the same output level by 2010. And that output was with millions of job losses.

Obviously automation has to account for that, or at least a substantial portion of that. And if we bring it up to the present day, output has increased 29% over 2000 while employees dropped by 2.5 million.

Two sides to this story. Baker ignores one of them.

EM:

I posted this in comments earlier. Perhaps you missed it?? I also believe it is fair to say much of the decrease did occur from 2000 onward. Do you know what a 4 and 5 axle CNC machine is?

I also believe it is fair to say much of the decrease did occur from 2000 onward. Do you know what a 4 and 5 axle CNC machine is?

Looking only at “jobs lost” gives a very narrow view of what is going on. If population is growing and production is growing and employment is growing and jobs in manufacturing stay level then manufacturing jobs are not keeping pace with everything else. One difficulty I have in arguing this issue with Dean is that he insists on looking at “productivity” in terms of the BLS definition of productivity, which in my view is kind of a tautology. If you have a secular increase in the proportion of precarious, low-paid, low productivity work then BLS productivity is not going to increase as much as it would otherwise. The economy we have today is not structurally the economy we had 30 or 40 or 50 years ago. So GDP-based comparisons that span decades are incoherent. My view is that late capitalism has been running on creative accounting for three decades, just as the Soviet Bloc did through the 1970s and 1980s. Chernobyl literally blew that scam up and I am afraid that climate change will be late capitalism’s slow motion Chernobyl.

Run,

“Do you know what a 4 and 5 axle CNC machine is?”

I wouldn’t even know where to start.

🙂

EM:

One would replace 3 jobs on the shop floor and the later would replace 4 jobs on the shop floor. One operator to stand by it and potentially load, unload, and check parts once and a while for quality purposes. It replaced automatics and manual machines for making metal parts. Flows of materials were also rearranged with production paths by function rather than by capability of operation.

Run,

It’s not just manufacturing.

I was a loan broker for a lot of my life. As such I spent many times in the offices of banks that I was selling my loans to. I remember in the 90s a Chase lending headquarters with 30 or 40 fax machines lined up against the wall in order to accept applications for car loans and leases. Faxes would ne taken to data entry clerks(I think on an IBM mini) who would digitize the applications which would then be underwritten by a buyer. There must have been 40 or 50 people doing this on a constant basis.

Flash forward ten years and that office had about 6 workers. Chase had been a part of a startup company that would process the apps over the internet. Finance managers in dealerships(or loan brokers like me) would digitize the applications as the point of sale. Getting it into the hands of the underwriters immediately with no other workers needed. It even got to the point where the apps were underwritten without an underwriter, simply being done by computer programs.

That company became DealerTrack.

https://www.dealertrack.com/public/about_dealertrack.asp

I cannot estimate how many jobs that eliminated in the banking industry. And it was much more efficient also.

That has to be true of all kinds of businesses.

Isn’t the real point that structural change is real and looking at aggregate statistics hides what is happening within cohorts (because most people train once for a lifetime career). This is what drives the politics. So young people have a totally different set of skills as older people on average. How many young touch typists are there.

There are lies, damned lies, and statistics. I believe the definition of what’s ‘productive’ has changed dramatically over the past 40 years. Today the FIRE sector is about half of GDP. A classical economist would consider almost none of this as ‘productive.’

Agreed! There is also the excessive health care costs in U.S. compared to other wealthy countries and military spending. Personally, I would add golf and yachts to the category of waste.

Sandwichman:

Thanks for the boost on healthcare costs. I agree