On the Horizon "After Obamacare"

Many of us have talked about bending the healthcare cost curve by changing the services for fee healthcare cost model to a model of better outcomes for those fees. This is precisely what the PPACA does. Phillip Longman based his book “Best Care Anywhere” on how the VA brought about such a change in the rendering of services to the nation’s veterans. Much of the cost savings today will come from a consolidated healthcare industry delivering healthcare more efficiently and at lower costs. STR has pointed out a few times without explanation the issue of consolidation within the healthcare industry, which if left unchecked, will cause its cost to increase. Both Phillip Longman and Paul Hewitt in a Washington Monthly article take-on the issue of healthcare industry consolidation “After Obamacare” and the monopolistic results. A keynote finding points to the future of America’s healthcare unless certain actions take place outside of the PPACA or whatever evolves.

“A frenzy of hospital mergers could leave the typical American family spending 50 percent of its income on health care within ten years – and blaming the Democrats. The solution requires banning price discrimination by monopolistic hospitals.”

As it stands and even with its faults, the PPACA is a viable solution to many of the issues faced by many of the uninsured and under insured; but in itself, it only addresses the delivery half of the healthcare problem. The other half of the problem rests with the industry delivering the healthcare and the control of pricing through the inherent monopolistic power coming and pushing the industry into greater integration of delivery. As Longman and Hewitt posit, “the message from Department of Health and Human Services stresses the vast savings possible through a less ‘fragmented’ and more ‘integrated’ health care delivery system. With this vision in mind, HHS officials have been encouraging health care providers to merge into so-called accountable care organizations, or ACOs”; while on the other side of Mall, “pronouncements from the FTC are about the need to counter the record numbers of hospitals and doctors’ practices that are merging and using their resulting monopoly power to drive up prices.“

This is not solely the result of the PPACA implementation as it has been going over the last decade and has increased in intensity with the signing of the PPACA.

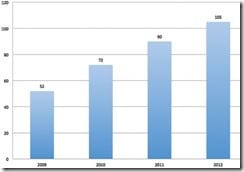

Announced Hospital Consolidations by Year

The result is a lessening of competition in and about major cities. The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) was used to measure competition in and around cities. The results of the HHI revealed an increase in the concentration of hospitals from mergers and acquisitions. Going from moderately concentrated in 1990 with an HHI numeric of 1570; the concentration can be described as highly concentrated in 2009 with a HHI of 2500 and some cities purely monopolistic at 10,000.

Today, much of the struggle exists between the providers of healthcare and the buyers of healthcare. Before the PPACA, this was broken down between the uninsured, the healthcare insurance companies, and the doctors, clinics, and hospitals. With little power, the uninsured absorbed the highest prices while the insured and the providers battled it out with the larger and more powerful of the two getting the better of the negotiation. Today and with the PPACA, many of the uninsured are insured with just the citizens of states not expanding Medicaid at risk. With growing consolidation of provider, the balance of power is shifting towards providers as competition lessens amongst them and they supersede the size of the buyers of healthcare. With the greater concentration of hospital and doctor networks come the higher prices often as high as 20% and sometimes higher. You can witness this phenomenon today with some of the well-known hospitals being able to demand higher fees from insurance companies and in concentrated markets.

– “Berkeley health care economist James C. Robinson studied the prices hospitals charge insurance companies (and, by extension, insured patients) for different procedures. In concentrated markets, the price for a pacemaker insertion averages $47,477; but in markets that remain comparatively competitive, the cost of the procedure averages $30,399.”

– “in concentrated markets, the average hospital makes a return of $20,000 above its direct costs on every angioplasty it performs. But in more competitive markets, while the margin is still astoundingly high, at $10,900, it is nonetheless 90 percent less than in concentrated markets.”

– “Massachusetts Attorney General Martha Coakley subpoenaed claims data (reflecting negotiated prices) and contracts from health plans and providers in her state. By examining the behavior of individual hospitals and physician practice groups, a strong link between market concentration and price was established. Within markets, prices charged for the same services typically varied by 200 percent or more. This variation correlated almost exclusively with ‘leverage’ – the relative market position of the provider.”

Very much my own experience between two hospitals reveals similar pricing inconsistencies. One out-of-town hospital in the top 5% for cardiac procedures; billed me for 8 days of hospitalization, catheterization, surgery and the associated doctors, radiologists, and nurses besides home care resulted at ~$80,000. Returning home and going to a major well known local hospital for a hospital walk-about of my heart (catheterization) resulted in a bill of $16,000 for a stay of less than a day, a cardiologist, and a couple of nurses beating me up as I wanted to leave (they took good care of me). One year later and I still do not feel 100%. In any case, the fees would have been lower in the out of town hospital. Why?

So what is the solution if the PPACA will not resolve it and the industry balks at controlling pricing? The authors, Phillip Longman and Paul Hewitt, propose rigorous action by the FTC; however, the FTC has in place a staff 22 lawyers and economists monitoring a $3 trillion industry. It is understaffed to take on such a large industry which would overwhelm it with legalese and paper.

Larger scale (and) integrated healthcare systems can (will) lead to better quality outcomes and efficiencies overcoming today’s fragmented healthcare system – “of specialists ordering up redundant tests and contraindicated drugs as they each treat one body part at a time, often with costly treatments of dubious effectiveness.” Promoting the integration of healthcare systems making them larger in scope also runs the risk of pricing abuse by the industry as evidenced today. In Maryland, pricing established by a review board has lowered costs from a high of 26% over the national average in 1976 to 4% less than the national average today. Maryland also has generous Medicare payments as set by an AMA committee, which has been blamed for lower costs experienced on the commercial side. Providers with their hand still opening the till for their own kind.

Bureaucrats establishing pricing is acceptable in some places; but then, there are those who believe their freedom is impinged upon by government keeping a watchful eye on business which the impinged upon have no control over anyway. If you do not believe so, attempt to negotiate your pending care in an emergency. You will be unconscious or dead first and will receive the care in such a state. The authors go on to suggest a hybrid regime of better antitrust enforcement tied to a “common carrier” methodology.

“A common carrier offers its services to the general public under license or authority provided by a regulatory body. The regulatory body has usually been granted ‘ministerial authority’ by the legislation created by it. The regulatory body may create, interpret, and enforce its regulations upon the common carrier (subject to judicial review) with independence and finality, as long as it acts within the bounds of the enabling legislation.”

This moves the competition to delivering the best product or service as opposed to leveraging market power to the market place due to size of the company. A similar methodology was used to prevent monopolistic railroads from offering better rates to other monopolistic enterprises such as Standard Oil and US Steel. Recently, courts used the same methodology with Microsoft. Historically same is being used in the transportation of oil, in phone service, internet, etc. Prices must be the same for the same service.

A similar logic should apply to healthcare. Nowhere does it makes sense that some providers are offered special rates by buyers when the service provided is the same.

“Uwe Reinhardt and other health care economists have noted, in this realm charging different people radically different prices for the same procedures does not even in theory lead to greater efficiency or lower prices. Rather, it just wastes enormous resources as different parties scheme to shift costs onto one another (buyers of service) through secret, special deals.”

In the end, it does not cost a hospital or a doctor to scan a patient through a CAT, X-Ray a patient, do a urine or blood test whether that person has insurance or not. So what makes sense for increasingly consolidated hospitals, doctors and clinics?

If for example, a market threshold was established setting the number of beds or doctors within a locality as controlled by a business was exceeded; that hospital and/or business might have to make public its pricing for all procedures and services to the general public which is already established on the establishment charge master. All customers whether insured or not or out of network would pay the same fees. Affiliated and independent doctors would also pay the same overhead charges. In effect, hospitals and doctors organizations would be similar to public utilities and a basic part of the community infrastructure.

Those organizations of doctors or hospitals which did not meet common carrier thresholds would be free to set their own pricing giving way to competition between common carriers and themselves in pricing, services, and procedures. The over ruling authority as to monopolistic tendencies would remain the FTC. The FTC would warrant competition between providers within certain areas.

References:

After Obamacare, Phillip Longman and Paul S. Hewitt, Washington Monthly January/February 2014

Darn snowblower wore me out, too tired for comments, so:

http://www.beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-transactions-and-valuation/house-committee-holds-hearing-on-healthcare-consolidation.html

Might be interesting.

Pointing us to more information would be great Rusty. My town dodged the major part of the snow but Logan was a mess.

http://www.partners.org/

This is the juggernaut in Boston area,,,routine care is much less cost in the burbs with better outcomes from smaller hospitals.

But the Big five are renowned internationally and certainly cutting edge treatments.

While I get ready for another snowblower session….

My two sources for a quick morning update

http://www.modernhealthcare.com

http://www.beckershospitalreview.com

Much of it is too detailed, but pick and choose the macro topics.

More later……..

Oh, and Kaiser of course.

I have never seen an analysis of what the result would be if you passed a law saying the medicare rate is all you can charge anyone for a medical procedure. Hospitals say they would go broke, but is that real?

Lyle:

No as Maggie Mahar would point out also. Remember what this is, a service for fees cost model. The more services I sell, the greater the costs and profits. There is a lot of fat in the market place.

Businesses that want to merge always claim they will go broke or cannot compete without merging.

Even small mergers in healthcare are damaging though, the following article discusses the closure of Malden General Hospital and the knock-on-effects that it has had (basically there has been a significant decline int he number of doctors in Malden, all of the family doctors etc relocated to be closer to the hospitals that are still open, and quality of health has deteriorated since the hospital that was built and founded by the community for the community became part of a for profit that decided shut it down in lieu of the promised modernization).

http://www.wickedlocal.com/malden/newsnow/x1793846239/HISTORICAL-PERSPECTIVES-The-Malden-Hospital-then-and-now?zc_p=0

Lyle:

Depends — if private insurance was to be dropped to Medicare but Medicaid raised to Medicare, and every patient covered, and the DRG methodology changed for those under 65, etc, etc, some hospitals could survive that,

In one sense it is already happening, private payer rates coming down, Medicare reimbursed trimmed in various ways, and exchange policies drifting toward Medicaid rates.

Health care tend to be a high fixed cost operation, and fixed costs are toughest to shed.

Too soon, too complicated to know.

One more quickly:

I have been getting reports of meltdowns in private insurer Customer Service and Provider Service departments. Too much change too fast.

In the way of anecdotal evidence:

Our insurance changed for the first time in 8 years to meet Obamacare standards, and as of today our old policy has been cancelled but the data and cards on the new policy are not issued. I do not blame the insurer for this.

So Mrs. R tried to get a prescription refilled and it is a nightmare. She of course blames me , because that is what husbands are for. 🙂

At the very least the month of January is going to be a nightmare.

No doubt that hospital costs are the reason why overall health care costs are so outrageously high. This is largely because hospitals can: 1) tack on a so-call “facility fee” to each and every hospital bill, and 2) charge Medicare and other insurers for test and procedures at rates that are four to five times higher than what non-hospital affiliated clinics and surgicenters can charge for them. Take way hospital facility fees and make hospital charges for test and procedure more in line with what non-hospital providers can charge for tests and procedures and then you’ll see hospital costs drop significantly. Most of these hospital facility fees and extra charges aren’t even used to provide better or more care at the bedside anyway; they are instead used to pay for a fat and bloated management structure and for too many worthless ivy-tower jobs in nursing education.

Cynthia:

I am going to disagree.

The present increase by some name hospitals is as the article implies, they are the “must haves” within the network. Secondarily, they can drive the prices they mandate due to the size of the market they control with the hospitals they have in place. Forcing them to divest in a similar manner at Bell Telephone, Standard Oil, US Steel, etc. will change the dynamics for the providers of healthcare. Medicare does not roll that easily and still maintains a cost margin 25% of what commercial healthcare has in terms of inflation.

Fixed costs are an issue; but, the justification of fixed costs as the reason for increased pricing is a flawed one ad hospitals can still profit with much lower pricing as pointed out by Hewitt and Longman.

Rusty,

“I have been getting reports of meltdowns in private insurer Customer Service and Provider Service departments. Too much change too fast.

In the way of anecdotal evidence:”

This should say “in the way of MORE anecdotal evidence”

.

Emike:

While wearing both my consultant hat and my writer/editor hat I deal with providers and provider associations on just about a daily basis. Most of what I do in those regards are proprietary and/or covered by professional ethics.

If you choose not to believe me, fine. If you want to do further research, fine.

So far today I have dealt with a national publication for medical practice administrators, a state medical board, a large regional newspaper and fielded a couple of minor questions from providers. And done 6 letters and 40 emails.

Time for lunch and the snowblower.

Either there needs to be a single payer system as in Canada/France, etc., or doctors need to be able to run the business based on profit/loss. The whole insurance layer with massive paperwork needs to be eliminated.

Hey Rusty…. it is 57 F. right now in Boston….tomorrow it will be 13 F.

We can’t break up the banks, what makes you think we can break up the hospitals, Run ? It’s just not gonna happen, especially since they’ve gained the status of being too big to fail. The only thing that is sure to happen is they’ll get a taxpayer bailout if they do fail.

Cynthia:

You do not have to break up hospitals; but as I suggested in the text, you can regulate them in a fashion as to control the chargemaster pricing they put forth. Make them transparent and give preference to those newbies in the industry.

And yes you can break up hospitals the same as you could Bell and other monopolies.