Bernanke (Mis)Explains the Effect of the Tech and Housing Bubbles

Discussing the failure of modern macro to incorporate the financial system into its models, Ben asks, why did the bursting of the housing bubble spank the economy so much harder than the dot bomb crash? He sez (courtesy Brad DeLong, emphasis mine):

…the decline in wealth associated with the tech bubble bursting [in 2001] and the decline in wealth associated with the decline in house prices as of, say, late 2008 was about the same–maybe even more on the [2001] stock [market] bubble. From a standard macro model or even one elaborated with financial factors, you would not have really thought that the housing bubble would have been more damaging than the stock bubble. Now the reason it was more damaging, of course, as we know now, is that the credit intermediation system, the financial system, the institutions, the markets, were far more vulnerable to declines in house prices and the related effects on mortgages and so on than they were to the decline in stock prices. It was essentially the destruction of the ability of the financial system to intermediate that was the reason the recession was so much deeper in the second than in the first.

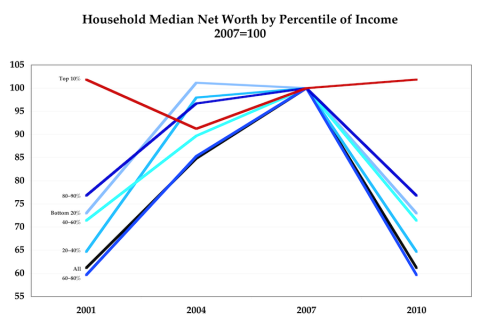

This familiar (and delusional) self-serving lionization of financial-industry “intermediation” completely misses the most significant difference between the two bubbles: one briefly dinged the wealth of a small proportion of the population — those who own stocks — while the other slammed hundreds of millions of people, permanently (click for larger):

(U.S. Census Survey of Consumer Finance)

Is it hard to imagine the effects of this picture on demand for real-world goods and services that humans consume, or the incentives for producers to invest, and produce (and sell) those goods and services?

Takeaway: if we want widespread prosperity and stability, we need a financial and political system that delivers…widespread prosperity. Pace (even) Paul Krugman, you don’t get it by making (and keeping) the rich people richer, and justifying it with the old “intermediation” rationalization.

Cross-posted at Asymptosis.

That chart really begs even more questions. What about the top 1%? How much money do the various deciles have, and what is their propensity to spend vs invest? Because I’d guess that at the 90th percentile, the propensity to spend all of it is still pretty high. But it is radically lower for the top 1%. So making them rich doesn’t create that much demand.

@simonator: You think the propensity to spend *all* of their *wealth* is really high for the 90%ers? I would seriously question that.

Would love to see data on this. In the meantime you may find this interesting:

http://www.asymptosis.com/wealth-and-redistribution-revisited-does-enriching-the-rich-actually-make-us-all-richer.html

I may have been unclear. I think that the propensity to consume varies more WITHIN the top 10% than between the bottom of the top 10% and and the other deciles.

Steve

thanks for this. it is hard for the Big People to imagine that anything that affects the little people could be as important as what affects Them.

and frankly, I think simonator is a victim of his education. all that ‘propensity to consume’ is part of the standard rationalization we call ‘economics,’ which simply does not describe the real world.

for one thing, “the rich” consume that which is provided by other “rich,” their consumption never needs to enter the economy of the poor.

I’d also add in 2008 we were running a huge trade deficit, and private sector debt had accumulated to much larger levels than during the tech bubble. Lastly, my hunch is teh tech bubble mostly affected the more affluent, where housing went right through all economic classes. Lastly the real estate market in totality dwarfs the tech sector.

@mmcosker: “the tech bubble mostly affected the more affluent, where housing went right through all economic classes. Lastly the real estate market in totality dwarfs the tech sector.”

Right. Those are exactly my points in this post, and in the graphic.

That is an excellent graph. I’m curious about the 60-80% line. Why is it below the others instead of between 40-60% and 80-90%?

@Carola: “the 60-80% line. Why is it below the others instead of between 40-60% and 80-90%?”

That is curious. I just checked the data and it seems right. (Haven’t gone back to the SCF to check, but will.) I can send you the spreadsheet if you like.

The only thing I can figure is that the runup and rundown in that segment’s house prices was more significant than for the other segments. Was that segment especially susceptible to ARMs sales and borrowing beyond their means?

I have to run out the door but will look at it more when I have time. Love to hear any insights from you.

Steve I think Minsky explained the runup perfectly:

Minsky argued that a key mechanism that pushes an economy towards a crisis is the accumulation of debt by the non-government sector. He identified three types of borrowers that contribute to the accumulation of insolvent debt: hedge borrowers, speculative borrowers, and Ponzi borrowers.

The “hedge borrower” can make debt payments (covering interest and principal) from current cash flows from investments. For the “speculative borrower”, the cash flow from investments can service the debt, i.e., cover the interest due, but the borrower must regularly roll over, or re-borrow, the principal. The “Ponzi borrower” (named for Charles Ponzi, see also Ponzi scheme) borrows based on the belief that the appreciation of the value of the asset will be sufficient to refinance the debt but could not make sufficient payments on interest or principal with the cash flow from investments; only the appreciating asset value can keep the Ponzi borrower afloat.

If the use of Ponzi finance is general enough in the financial system, then the inevitable disillusionment of the Ponzi borrower can cause the system to seize up: when the bubble pops, i.e., when the asset prices stop increasing, the speculative borrower can no longer refinance (roll over) the principal even if able to cover interest payments. As with a line of dominoes, collapse of the speculative borrowers can then bring down even hedge borrowers, who are unable to find loans despite the apparent soundness of the underlying investments.[5]

“for one thing, “the rich” consume that which is provided by other “rich,” their consumption never needs to enter the economy of the poor. “

Don’t take this as a typical Republican talking point of “don’t increase taxes on the rich because they’re the job creators”, recognizing that as a completely different issue. But when you say the consumption of the rich doesn’t enter the economy of the poor, whom do you think employs maids, gardeners, nannies, chauffeurs, etc?

m. jed – what income levels are we talking about, top 10%, 5%, 1%? In the industry I work in, I deal with a lot of people in the top 10% (not many chauffeurs there). Other than the top 1%, those folks spend a lot of money, and IMO it does go to the working class though I cannot say how much- would love to see a study. They do save as well, but not nearly all of it. Higher income households are also older peaking at retirement, which makes sense. Again not really looking at the 1%.

mmcosker,

risking speculating on what coberly meant in his comment, I’m guessing the implication was that those in the 1% are in their own orbit and don’t interact with the poor. my point – and by inference yours too – was that those jobs are almost exclusively provided by the top 1% (or higher)

jed

unless they hire more maids, or raise their wages, their increased wealth does not reach the poor.

in general this does not happen.

i believe Keynes observed this also, though he would have phrased it differently: it is possible to have a wealthy class without any “trickle down.”

i believe the French aristocracy may have discovered this too late.

don’t know whether link will or won’t but verifies what Steve noted and that i’ve tried getting across since 2000-01 on various sites from CBS to PruBear but which tends to be ignored.

http://www.faculty.fairfield.edu/faculty/hodgson/Courses/so11/stratification/IncomeWealth.png

[I’m thinking one of the ‘Wolffs'[w/Levy?] has also looked into this as well as someone at UCB – but no doubt the distribution became very skewed and impacted real market and credit.]

Thanks Steve

Coberly,

Don’t forget Keynes but read Marx’s Capital [all 3 vols] as well as Joan Robinson and Kalecki — Guarantee the perspectife will deepen and broaden.

su amigo juan

Ah yes, the Real Solution –

”If the Treasury were to fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them at suitable depths in disused coalmines which are then filled up to the surface with town rubbish, and leave it to private enterprise on well-tried principles of laissez-faire to dig the notes up again (the right to do so being obtained, of course, by tendering for leases of the note-bearing territory), there need be no more unemployment and, with the help of the repercussions, the real income of the community, and its capital wealth also, would probably become a good deal greater than it actually is. It would, indeed, be more sensible to build houses and the like; but if there are political and practical difficulties in the way of this, the above would be better than nothing.”

[Keynes, Gen Theory, Bk III, Ch 10, No. 6]

Well, it would be the Real Solution if there were not real honest to god limits to public/private partnership.

Cesar o juan o yon o rigoberto o julio o arturo o simplemente su amigo [companero de alta verapaz]

”Except in a socialised community where wage-policy is settled by decree, there is no means of securing uniform wage reductions for every class of labour. The result can only be brought about by a series of gradual, irregular changes, justifiable on no criterion of social justice or economic expediency, and probably completed only after wasteful and disastrous struggles, where those in the weakest bargaining position will suffer relatively to the rest. A change in the quantity of money, on the other hand, is already within the power of most governments by open-market policy or analogous measures. Having regard to human nature and our institutions, it can only be a foolish person who would prefer a flexible wage policy to a flexible money policy, unless he can point to advantages from the former which are not obtainable from the latter. Moreover, other things being equal, a method which it is comparatively easy to apply should be deemed preferable to a method which is probably so difficult as to be impracticable.”

”The result can only be brought about by a series of gradual, irregular changes, justifiable on no criterion of social justice or economic expediency, and probably completed only after wasteful and disastrous struggles…”

Or same as the long run decline of real weekly wages for nonsupervisory employees in los estados unidos – Peak ws 1972 and cap has still been unable to recover ‘golden age’ RATE of profit no matter how much greater the mass.

long run, transcyclic, retrogression.

I agree with Carola. I can’t figure out what the Y-axis means. Having some units on it would help.

It’s hard to rationalize the various positions of the quintile lines, and especially the ALL line.

Are the values normalized in some non-obvious way?

Cheers!

JzB

@JzB:

No I thought they were normalized in an obvious way: 2007 level for each segment is set to 100. Other years are relative to that.

Being these charts are on total net worth, the apparent mix up of strata could be found in the percentage of wealth outside of the real estate wealth.

The other side would be that the 60 to 80% group might have been where the most action was and thus higher pricing achieved relative to the starting home price. This would be the group with a lot of trading up going on? Where as the other lower groups would have been the new home buyer which implies a limit to the rise in that home price range, thus less percent of income.

@Daniel Becker:

That’s exactly my surmise. Would require more digging to confirm.

But the overall shape of the graph still tells a pretty profound, convincing, and coherent story, regardless of the details.

Steve Roth

no the normalization is not obvious, except to you.

i hate to say this, but it requires a bit of mind reading, even though you “said” it, because it is a very idiosyncratic way of presenting the information.

that said,

i don’t like comparisons of “percents”. they are almost always misleading. and even worse, they are beside the point: we don’t make life better for ourselves by chasing percents, or comparing ourselves to others.

that doesn’t mean i disagree with what i take to be the substantive point behind Roth’s post.

@Steve “The only thing I can figure is that the runup and rundown in that segment’s house prices was more significant than for the other segments. Was that segment especially susceptible to ARMs sales and borrowing beyond their means?”

That would be my guess. Maybe the 80% and up groups bought houses in the areas that held their value better, and/or had more financial knowledge/advice to avoid ARMs. But I still would have thought that the 40-60% group would have been in roughly the same boat as the 60-80% group, unless they are just much less likely to get a mortgage.

Steve –

I completely missed the 2007 = 100.

You’re right, it is obvious. My bad (eyesight)

Thanx

JzB

juan

all three volumes?

i think my library threw away their copies because the are “old” books.

Jazz

well, that shoots me down. but

you, an expert, had to ask, and having asked, you now find it “obvious.”

while stupid old me, figured it out myself and still thought Steve could do a better job making it “obvious” to the un-expert.

solipsism is not a good political strategy.