Guest post: Want a Flat Tax? I Got a Flat Tax for You

Guest post by Steve Roth

Want a Flat Tax? I Got a Flat Tax for You

crossposted with Asymptosis

One percent of financial assets. Personal and corporate. Annually.

With somewhere north of $55 trillion in U.S. financial assets out there (2009, down from $63 trillion in 2007), a Financial Assets Tax would generate more than $550 billion in annual revenue.

What could we do with that revenue? Here are some options:

• Eradicate taxes on corporate profits, dividends, and capital gains, and cut income taxes by between 22% and 51%. (Depends on which tax year you’re looking at; this for 2007-09. NIPA Table 3.2.)

• Pay off some of our national debt, invest in productive infrastructure to build true national wealth, greatly expand the EITC (and index it to unemployment) to turbocharge the real economy, or…

• Some equitable and economically efficient combination of the above

Why should we do this?

Simple: greater prosperity and greater equality. Both.

This idea seems to have far greater upsides than downsides. But I’ve undoubtedly missed some things, which I hope my gentle readers will fill in.

Here are some of the issues involved:

Innovation and growth. Naysayers (mostly — surprise! — large holders of financial assets) will scream that THIS PROPOSAL TAXES SAVINGS!!!, which for not-very-well-hidden and supposedly moralistic reasons is seen as BAD!!! (As my friend Gabriel in England said to me once, “Yes, well, we shipped all our Puritans over to you, now didn’t we?”)

Their post-hoc rationalization for that faux moralizing: savings are (more accurately: can be) used for investment, by which they mean (in this instance) fixed investment in productive assets — structures, equipment, software, etc. We want to encourage fixed investment, right? It drives growth (and long term, employment), and builds national wealth and prosperity, right? The answer to those questions is “Yes.”

But when they start objecting to the tax because it “will hurt poor people,” raise at least one eyebrow. First — as usual — they’re confusing flows with stocks. Savings is a flow. Money from savings goes into the stock of financial assets — cash in mattresses, bank account balances, CDs, stocks, bonds, collateralized debt obligations, etc.

But that misconception aside, talk about being wrong by 180 degrees. This proposal does indeed discourage saving — in favor of real investment.

Remember: there are only five things a person or company can do with a dollar of income:

1. Spend it on consumption (buy food or office supplies, pay wages for ongoing operations, etc.)

2. Invest it (to create or purchase — hence spur creation of — real assets)

3. Save it (“invest”/store it in financial assets — effectively or actually lending it out)

4. Pay off loans (basically saving, but on the other side of the balance sheet)

5. Pay taxes

If a dollar is “saved,” it is by definition not invested. (Though it or an identical, fungible equivalent might flow back out of the pool of financial assets to be spent on real investment –or on consumption, loan payoffs, or taxes.)

If people and companies sock away their income in financial “investments” (save it) and just enjoy the returns, one percent of those returns will be skimmed off every year. (Not terribly onerous, given that hedge-fund “investors” pay large multiples of that and still make piles of money for doing nothing.)

If, on the other hand, people and companies use that money to build houses, apartment buildings, malls, office buildings, amusement parks, and factories, invest in new equipment and software, or spend it on those deucedly hard-to-measure but massive contributors to our national asset base — education, training, research, and development — the assets they create won’t be hit by this tax.

And the ongoing income generated by those real assets will be taxed at a far lower rate.

Alternatively, the income that isn’t saved might be spent on consumption — increasing monetary velocity and aggregate demand, and making the whole swirling pie that is the economy, bigger.

If you think collateralized debt obligations are valuable national assets, you should hate this tax. If you think — correctly — that as Kuznets and many others have pointed out, real assets constitute true national wealth (though many of the most important real assets, like ideas, knowledge, skills, and “organizational capital,” are intangible and unmeasurable), you should love this tax.

What do we mean by financial assets? There are some gray areas that would need to be sorted out (insurance, pensions, etc.), but most financial assets quack like ducks. For a quick list, take a look at the column headings in Table 2A the of the Fed’s analysis of the Census’s 2009 Panel Survey of Consumer Finances (XLS):

Transaction accounts

Certificates of deposit

Savings bonds Bonds

Stocks

Pooled

investment funds

Retirement accounts

Cash value life insurance

Other managed assets Other

We might even want to include cash (actual dollar or euro bills). Why should we encourage cash in mattresses? TBD.

My friend Steve tentatively suggested “anything that’s traded on an exchange,” which seems like a good idea except it would encourage Wall Streeters to move towards assets that are traded off-exchange, over the counter. We’ve seen the effects of that.

What about incentives and economic distortions? How much would this tax distort economic decisions? Think: Nobody, ever, says “I’m not going to get wealthy because I’d have to pay taxes.” Why? Ask any of Jane Austen’s heroines: because there’s no substitute for wealth.

Earned income? Quite otherwise, because there’s a very good substitute for working to earn money: leisure. Spending time with the kids, playing golf, writing overly long and abstruse economic blog posts, watching NASCAR, assembling intricate miniatures of Civil War battle scenes.

In economic terms, the demand for employment is quite elastic because there’s an attractive substitute. The demand for wealth is quite inelastic, because there just ain’t no substitute for being rich.

The Financial Assets Tax would provide a very slightly lower incentive to earn money every year (anyone care to do the arithmetic?), but nothing like the disincentive that results (in theory, to some greater or lesser degree) from high marginal income tax rates, corporate profit and dividend taxes, etc.

The biggest incentive — arguably an economic “distortion,” but every tax except maybe land value taxes is distortionary — would be to spend on real investment (and consumption) instead of saving.

But that incentive would actually compensate for an inherent distortion resulting from the nature of financial assets, which are at root an artificial creation: Financial assets don’t decay and depreciate like real assets do. After ten years (or whatever), you still have the initial capital, plus the returns, which is not true with fixed investments. So fixed investments have a big disadvantage when they’re competing for “investment” dollars. A Financial Assets Tax would to some degree correct for that inherent market distortion/inefficiency.

Too big to fail. I’ve pointed out that the financial economy — the trade in financial assets — is many time larger (40x, 50x?) than the real economy — trade in goods and services. And it’s arguably many times larger than is necessary to lubricate and intermediate the real economy. And innumerable wise voices have pointed out the negative externalities of this excessive size: systemic risk of financial-market meltdowns that trash the real economy, gross misallocation of financial and human resources, etc.

There have been some salutary if rather timid proposals to address this via taxes on financial transactions — the flows — to compensate for those externalities and shrink the sector. But this proposal for taxing the stock of financial assets could be a superior alternative. I’ll leave it to others, for now, to analyze the pros and cons of those two alternatives.

What about private residences? This is both a large segment of fixed investment, and kind of a special case — different from business investments because the value derived isn’t in the ability to produce more, saleable goods and services, but having a roof over your head.

Here’s the functional scenario: you’ve got half a million dollars in financial assets, and you want to build a half-million-dollar house. Here are the two ends of the spectrum — you can land anywhere in between:

1. Sell all your financial assets and spend the money to build the house.

2. Sell $50,000 of financial assets for the 10% down payment on a loan, and borrow the rest.

Your taxes on the house asset are the same either way. But in scenario 2, under the Financial Asset Tax proposal you also pay tax every year on the $450,000 in financial assets you’re still holding. So it’s less attractive. It effectively increases the interest rate on your loan by 1%.

Putting aside for the moment all the other factors you personally consider (liquidity, risk, return, peace of mind, etc.): which of these scenarios — if repeated by millions of people over decades — contributes more to national wealth and prosperity? Which should the tax system encourage? (Because every tax system encourages something.)

The first scenario reduces the value of financial assets by reducing demand for them; the second increases it. As Dirk Bezemer has explained, borrowing-driven booms in financial asset values drain resources from the real economy, and so are associated with slower real-sector growth. The second scenario also effectively prints $450,000 in new money, causing more inflation pressure, which puts pressure on the Fed to raise interest rates, which discourages real-sector investment.

Which one should we encourage — borrowing or real investment? You decide. (And yes: we should also eradicate the insanely economically inefficient — and regressive — mortgage interest deduction, which makes the second scenario so much more attractive.)

What about volatility? The value of U.S. financial assets (nominal — not inflation-adjusted) fell by 13% from 2007 to 2009 (assets held by U.S. households, nonprofits, and nonfarm, nonfinancial businesses — Fed Flow of Funds TFAABSNNCB + TFAABSHNO). Under this proposal, that would result in a huge hole in the Federal budget.

Personal income went up by 2% (nominal) over that period (NIPA Table 2.1). This tells you: the revenues from a Financial Assets Tax would be much more volatile than from income taxes, because asset values are far more volatile than incomes.

But let’s step back: Every reasonable person (this excludes large portions of the Republican and Tea Parties) agrees that it’s smart for government to spend more in the bad times (causing a government deficit), and less in the good times (causing a surplus). It’s intuitively obvious (thanks to Keynes), we’ve seen it work (1939 passim), and all sorts of old and new economic theory, notably Modern Monetary Theory, supports it in spades.

The problem, of course, is politicians. When bad times hit and government revenues are down, they panic like scared children. They don’t remember (or look forward to) the good times, like when the federal debt was plummeting during the Clinton boom/tax-increase/surplus years. So they do exactly the opposite of what common sense and prudent wisdom prescribe: they cut spending. The volatility of the Financial Asset Tax could contribute greatly to this panic-driven policymaking.

My only reply: it is to be hoped that the economic efficiency of the Financial Assets Tax — the growth and prosperity it engenders, especially in the real sector of the economy — would over the long term overwhelm the negative effects of political mismanagement. Other suggestions to overcome this difficulty, much appreciated.

What about evasion and offshoring? Stocks of financial assets are easier to track and harder to hide than flows of income. They have to be stored somewhere. Since they’re not ongoing flows, they can’t be laundered and hidden as easily through multiple international pipelines and entities. People will still use secret accounts in the Bahamas to hide their money (as long as we allow the Bahamas bankers to get away with it; the Swiss can’t anymore…). And yes, people and businesses will figure out new schemes to evade this tax. People will always figure out ways to commit fraud. A simple tax on an easier-to-track item will make it harder for them to do so.

Since we’ll tax domestic entities’ financial assets no matter what country those assets happen to be stored in (just as we tax worldwide income now — at least of natural humans) — people and businesses will have less incentive to keep piling up their treasure in financial (and real) assets overseas. They can bring it home at no cost (they’re paying taxes on it in either place) hopefully investing it in real assets here.

Why not a consumption tax or VAT instead? I don’t actually know much about these, so take this for what you will.

Those taxes are good because they don’t penalize or kill incentives for work, innovation, and real earnings (personal earned income and real — nonfinancial — corporate profits). But both of them, as I understand the proposals and real-world examples I know of, tax investment spending at the same rate as consumption spending. So they’re not really just consumption taxes. They’re also investment taxes. That’s not good. I assume there are carve-outs to correct for that, but the more carve-outs you put in place for various and sundry reasons, the more messed up, gamed, and inefficient tax regimes become. The Financial Assets Tax makes things much more clear and simple. That’s one value of a flat tax.

Also: to make consumption taxes reasonably progressive, the top marginal rates have to be high, maybe even greater than 100%. Imagine a million-dollar consumer paying two million dollars in taxes on that consumption. You think that’s gonna happen?

How do you phase it in? This would be a big change in the rules of the game. It’s both fair and efficient to give people time to adapt. I would do it based on: 1. person versus company, 2. age, and 3. quantity of financial assets.

For people: Give a few year’s warning, then in the first year, people 30 and under with more than $5 million in financial assets would be subject to the tax. (I am rather unconcerned with these people’s well-being, or with their ability to adapt to the new regime over the course of their lives.) Increase the age and reduce the cutoff — perhaps ending at around four to six times median income — over ten or fifteen years. Other personal tax rates should decline in concert. For companies: Give two or three years warning, then replace the tax on C-corp profits with the Financial Assets Tax. They’ll adapt just fine — mainly by shifting from financial investment to real investment, but also probably by increasing dividends, putting the money back out there where it can be intelligently allocated by the wisdom of the crowds rather than by CEOs’ purported omniscience. Maybe this will also encourage corporations to hire CEOs who are real business managers, rather than practitioners of financial prestidigitation.

Oh yeah: equity! Don’t change the channel, America. It matters. It especially matters to those who don’t have it. (Few of whom are reading this.) But excessive inequity hurts the rich too, in the long run, because it kills long-term national prosperity. Economically efficient policies that deliver greater equity also deliver greater long-term prosperity. Even the rich get richer under progressive policies (except maybe the very, very rich). The poor and the middle class get far richer.

What do we mean by equity and inequity? Are we talking about income inequality? Feh.

Our world in pictures (regular readers will recognize some of these, but some are all new):

Source: Piketty, T. and Saez, E. 2007. Income and Wage Inequality in the United States 1913-2002. In Atkinson, A. B. and Piketty, T. Top Incomes Over the Twentieth Century: A Contrast Between Continental European and English-Speaking Countries, Oxford University Press, Chapter 5; series updated by the same authors. Hat tip Catherine Rampell.

Source: Piketty, T. and Saez, E. 2007. Income and Wage Inequality in the United States 1913-2002. In Atkinson, A. B. and Piketty, T. Top Incomes Over the Twentieth Century: A Contrast Between Continental European and English-Speaking Countries, Oxford University Press, Chapter 5; series updated by the same authors. Hat tip Catherine Rampell.

Source (pdf). The tax info here is just an added bonus feature, showing that above about $60K or 80K in income, our tax system (local, state, federal combined) isn’t progressive at all. The people making $160K pay the same share of their income pool as the people making $160 million.

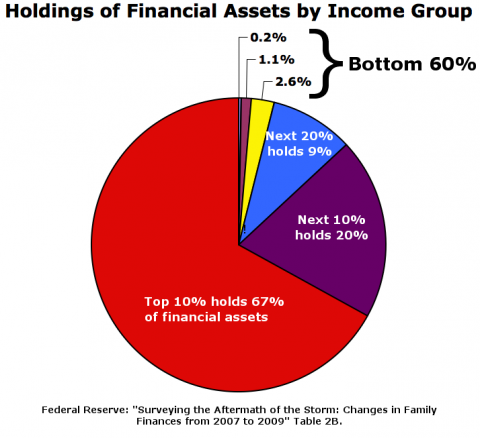

Source (pdf). The tax info here is just an added bonus feature, showing that above about $60K or 80K in income, our tax system (local, state, federal combined) isn’t progressive at all. The people making $160K pay the same share of their income pool as the people making $160 million.  Sources (PDF): Sylvia A. Allegretto, Economic Policy Institute; Edward Wolff, unpublished 2010 analysis of the U.S. Federal Reserve Board, Survey of Consumer Finances and Federal Reserve Flow of Funds, prepared for the Economic Policy Institute. Another hat tip to Catherine Rampell.

Sources (PDF): Sylvia A. Allegretto, Economic Policy Institute; Edward Wolff, unpublished 2010 analysis of the U.S. Federal Reserve Board, Survey of Consumer Finances and Federal Reserve Flow of Funds, prepared for the Economic Policy Institute. Another hat tip to Catherine Rampell.

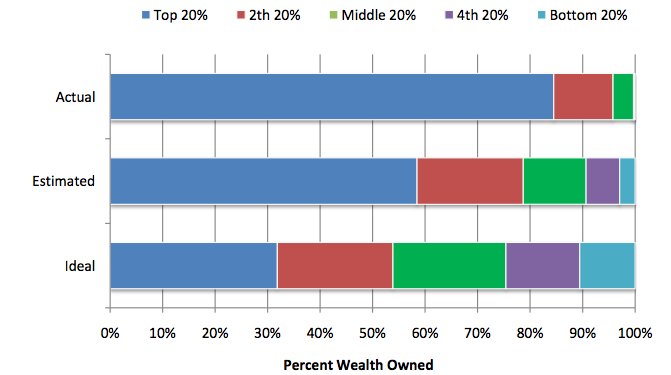

Figure 2. The actual United States wealth distribution plotted against the estimated and ideal distributions across all respondents. Ariely and Norton, 2010 (PDF).

The bottom 80% gets about 40% of the income.

The bottom 80% owns about 15% of the wealth.

You want freedom? Look to your bank balance. You want opportunity? Look to your bank balance. You want time and space enough to innovate and be an entrepreneur, without the disincentive (not to mention embarrassment and inconvenience) of potential financial catastrophe? You want to buy birthday presents for your kids, get their teeth fixed, or put them through good colleges, maybe take a family vacation every year or two? You know where to look.

But if you’re not in the top 20%, you’re not looking at shit. So who pays the tax? You can see the ownership breakout for financial assets sliced various ways in the aforementioned Fed/Census Bureau table (XLS). Here’s the breakout for personal holdings, by levels of income:

This would be a very progressive tax, because the the distribution of wealth is very regressive. It would compensate quite effectively for all our country’s regressive taxes, like payroll taxes, sales taxes, property taxes, and cut-rate taxes on financial investments.

I don’t have the wherewithal to calculate the total resulting progressivity. Perhaps it would be excessive, to the point of economic inefficiency (though I doubt it).

If we thought that was the case, we could reduce the rate from 1% to .75% or .5%, and continue income and other taxes at higher rates. Subject to discussion.

Bottom line: If we want widespread freedom, opportunity, innovation, entrepreneurship, and healthy, happy living, all feeding on itself in a virtuous, self-perpetuating cycle, then broadly based wealth distribution is at least one necessary condition. A tax on financial assets would be an (economically) efficient and effective means to move towards that goal.

Oh, and not that this matters, but in the short and medium term, while pies are growing and boats are rising, tens of millions of people get to suffer less. But maybe it does matter, because in the long run, you know…

Blogger stripped formating for some reason when published…I will repai and delete this comment when done.

@jazzbumpa .. ‘Rethugs’ don’thave to assault new deals, or great societies… they’re growing themselves past sustainabilty, as predicted by their ideoligical opponents.

ANYway..

Interesting and well thought out / written post.. I’ve read it three times now.. each time garnering more understanding, but your conclusion brings it all back to the same, wealth-distribution theme. Without the ideological debate surrounding the how/why of wealth distribution; allow me to reference your, “Actual / Estimated / Ideal” chart.. and specifically what I’m sure you’ label as “Worst-case”, the ‘Actual‘ distribution.

But first, 3 bits of data normalization: 1) human nature 2) age 3) capitalism

1) No matter how we try for social-engineering by tax; some people are just more capable, and more motivated than others. They will accumulate more wealth no matter how we tax them.

2) Put simply; a 20 year-old is SUPPOSED to have a tiny fraction of the accumulated wealth of a 60 year-old.

3) Aside from literal Socialism, the average business owner MUST have much greater wealth than the average employee.. even if it’s just the net-worth of the company he owns, creating those jobs.

Applying those three normalizers to even the infamous ‘L-Curve’, flattens it out significanlty. Flat enough for the average Capitalist to not see a huge problem.

If we’re gonna address a problem in wealth distribution; I’d suggest looking at how the opportunites for those on the lower-end are eroded by a government that gobbles up something more than one-fifth of the GDP.. and more spefically, how a huge chunk of the gobble is used to not only discourage productivity, but to subsidize a lack of it.

Finally a really well thought out idea on how to actually soak the rich!!!!

Kudos! Even if this is totally never going to be instituted..

Islam will change

RweTHEREyet: “If we’re gonna address a problem in wealth distribution;”

How about actually leveling the playing field? Give poor children both educational and extra-curricular support and opportunity, so that socio-economic mobility is uniform for all children. 🙂

Hmm. I don’t think that I said that right. Social mobility could be uniform in a caste society. What I mean is that a person’s socio-economic class at age 50 or so should have very little relation to their parent’s socio-economic class at age 50 or so. Then we have a pretty level playing field.

We’ll agree here, mostly. The theory behind school-funding is supposed to be fair. You’d find me as an ally, “fixing” that problem..

And too, we won’t disagree much on the problem of “passed-down” scocio-economics. If you noticed; my normalizers were a per-person deal, independent of inheritance.

But geez.. where can you draw a line ? We can put aside the problem about wealth and “head-starts” that come from taking over a family business. Liquidating a business serves no good purpose, in a long-run… and in its own way, discourages one from building a business that’s wealth goes well into whatever the ‘death-tax’ dictates. Now.. where we might agree, is that a death-tax on a sizeable estate “encourages” one to spend, rather than amass an estate. The debate there, is at what point does saving for the future become counter-productive.. especially not knowing what the future holds.

But as stated.. I still believe the biggest eroder of opportunity .. for ANYone.. is a government eating up +20% of GDP, all the while punishing productivity, and rewarding the lack of it.

Yeah, that probably explains why the US is among the wealthiest counties in the world, on a per/capital basis, and why the government’s share of national product in most of the others in our league is higher still. It’s because government is such a burden.

I personally AGREE with that.. I’m just addressing all the fuss about wealth-distribution.. : )

An eloquent, moving column today in the Washington Post by former Bush speechwriter Michael Gerson about budget cutbacks. Seriously. Don’t miss it. It’s at http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-real-world-effects-of-budget-cuts/2011/04/06/AFpEFXxC_print.html.

Inflating assets is why America exists and the slightest disincentive in that regard would be the end of it. Such a tax cannot possibly be proposed or enacted and even if it did America would be over.

And government then regurgitates that 20% into the economy by paying its employess and contractors. It builds some roads and buildings. It buys lots of goods and services. Hmm, looks like government is just another participant in the economy, like some large corporate entity competing for the hearts and minds and business of its citizens. So what’s wrong that? And where is the reward for the lack of productivity?

Somewhere in there you explain why the economy does so well under tax-and-spend liberals like Ike.

Somewhere in there you explain why the economy does so well under tax-and-spend liberals like Ike.

Somewhere in there you explain why the economy does so well under tax-and-spend liberals like Ike.

The historic, healthy limit is indeed 20%, and there’s nothing wrong with that. My fault for failing to note that it’s now 26%

The subsidization of lower productivity is subtle and varied. Earned-income-credit is part of it.. farm/corporate welfare is part of it.. and the vast, overlapping social programs that leave a single parent of two better of financially earning $16,000, than they’d be earning $56,0000.

If you wanna get into that stuff, I’ll accommodate you, but not in this thread… it’s get’s into un-politically-correct ideology.

Forgot the big one.. Government spending (and future spending of unknown, epic proportion) to subsidize and THEN bail out, mortages for people not nearly productive enough to have serviced them in the first place.

To the evil of monarchy we have added that of hereditary succession; and as the first is a degradation and lessening of ourselves, so the second, claimed as a matter of right, is an insult and imposition on posterity. For all men being originally equals, no one by birth could have a right to set up his own family in perpetual preference to all others for ever, and tho’ himself might deserve some decent degree of honours of his contemporaries, yet his descendants might be far too unworthy to inherit them. One of the strongest natural proofs of the folly of hereditary right in Kings, is that nature disapproves it, otherwise she would not so frequently turn it into ridicule, by giving mankind an ASS FOR A LION.

Secondly, as no man at first could possess any other public honors than were bestowed upon him, so the givers of those honors could have no power to give away the right of posterity, and though they might say “We choose you for our head,” they could not without manifest injustice to their children say “that your children and your children’s children shall reign over ours forever.” Because such an unwise, unjust, unnatural compact might (perhaps) in the next succession put them under the government of a rogue or a fool. Most wise men in their private sentiments have ever treated hereditary right with contempt; yet it is one of those evils which when once established is not easily removed: many submit from fear, others from superstition, and the more powerful part shares with the king the plunder of the rest.

From “The Pamphlet” by Thomas Paine

To the evil of monarchy we have added that of hereditary succession; and as the first is a degradation and lessening of ourselves, so the second, claimed as a matter of right, is an insult and imposition on posterity. For all men being originally equals, no one by birth could have a right to set up his own family in perpetual preference to all others for ever, and tho’ himself might deserve some decent degree of honours of his contemporaries, yet his descendants might be far too unworthy to inherit them. One of the strongest natural proofs of the folly of hereditary right in Kings, is that nature disapproves it, otherwise she would not so frequently turn it into ridicule, by giving mankind an ASS FOR A LION.

Secondly, as no man at first could possess any other public honors than were bestowed upon him, so the givers of those honors could have no power to give away the right of posterity, and though they might say “We choose you for our head,” they could not without manifest injustice to their children say “that your children and your children’s children shall reign over ours forever.” Because such an unwise, unjust, unnatural compact might (perhaps) in the next succession put them under the government of a rogue or a fool. Most wise men in their private sentiments have ever treated hereditary right with contempt; yet it is one of those evils which when once established is not easily removed: many submit from fear, others from superstition, and the more powerful part shares with the king the plunder of the rest.

From “The Pamphlet” by Thomas Paine

Soak the rich??? How about simply asking the rich to give back to the system that has made their wealth accumulation the possibility that came to fruition.

There’s a reasonable argument that while 1/2 the population pays no federal income tax, and the upper 2% pay 40% of the federal income taxes, there is already an ample, progressive give-back.

There is no give-back problem.. the problem lies in how much the government spends.

Are Mitch McConell and the Other Republican (Confederate) Bumfluffs ######:

1930s

Even by Depression standards, the Tennessee Valley region was in sad shape in 1933. Much of the land had been farmed too hard for too long, eroding and depleting the soil. Crop yields had fallen along with farm incomes. The best timber had been cut. TVA developed fertilizers, taught farmers how to improve crop yields, and helped replant forests, control forest fires, and improve habitat for wildlife and fish. The most dramatic change in regional life came from the electricity generated by TVA dams. Electric lights and modern appliances made life easier and farms more productive. Electricity also drew industries into the region, providing desperately needed job

Are Mitch McConell and the Other Republican (Confederate) Bumfluffs ######:

1930s

Even by Depression standards, the Tennessee Valley region was in sad shape in 1933. Much of the land had been farmed too hard for too long, eroding and depleting the soil. Crop yields had fallen along with farm incomes. The best timber had been cut. TVA developed fertilizers, taught farmers how to improve crop yields, and helped replant forests, control forest fires, and improve habitat for wildlife and fish. The most dramatic change in regional life came from the electricity generated by TVA dams. Electric lights and modern appliances made life easier and farms more productive. Electricity also drew industries into the region, providing desperately needed job

The Ku Klux Klan rose to prominence in Indiana politics and society after World War I. It was made up of native-born, white Protestants of many income and social levels. Nationally, in the 1920s, Indiana had the most powerful Ku Klux Klan. Though it counted a high number of members statewide, (over 30% of its white male citizens[93]) its importance peaked with the 1924 election of Edward Jackson for governor. A short time later, the scandal surrounding the murder trial of D.C. Stephenson destroyed the image of the Ku Klux Klan as upholders of law and order. By 1926 the Ku Klux Klan was “crippled and discredited.” [94]

D. C. Stephenson, Grand Dragon of the Indiana Klan. His conviction for murdering a young white schoolteacher in 1925 devastated the Indiana Klan.

D. C. Stephenson was the Grand Dragon of Indiana and 22 northern states. He led the states under his control to separate from the national KKK organization in 1923. In his 1925 trial, he was convicted for second degree murder for his part in the rape and subsequent death [95] of Madge Oberholtzer. After Stephenson’s conviction in a sensational trial, the Klan declined dramatically in Indiana. Historian Leonard Moore concluded that a failure in leadership caused the Klan’s collapse:

Stephenson and the other salesmen and office seekers who maneuvered for control of Indiana’s Invisible Empire lacked both the ability and the desire to use the political system to carry out the Klan’s stated goals. They were uninterested in, or perhaps even unaware of, grass roots concerns within the movement. For them, the Klan had been nothing more than a means for gaining wealth and power. These marginal men had risen to the top of the hooded order because, until it became a political force, the Klan had never required strong, dedicated leadership. More established and experienced politicians who endorsed the Klan, or who pursued some of the interests of their Klan constituents, also accomplished little. Factionalism created one barrier, but many politicians had supported the Klan simply out of expedience. When charges of crime and corruption began to taint the movement, those concerned about their political futures had even less reason to work on the Klan’s behalf.:

The Ku Klux Klan rose to prominence in Indiana politics and society after World War I. It was made up of native-born, white Protestants of many income and social levels. Nationally, in the 1920s, Indiana had the most powerful Ku Klux Klan. Though it counted a high number of members statewide, (over 30% of its white male citizens[93]) its importance peaked with the 1924 election of Edward Jackson for governor. A short time later, the scandal surrounding the murder trial of D.C. Stephenson destroyed the image of the Ku Klux Klan as upholders of law and order. By 1926 the Ku Klux Klan was “crippled and discredited.” [94]

D. C. Stephenson, Grand Dragon of the Indiana Klan. His conviction for murdering a young white schoolteacher in 1925 devastated the Indiana Klan.

D. C. Stephenson was the Grand Dragon of Indiana and 22 northern states. He led the states under his control to separate from the national KKK organization in 1923. In his 1925 trial, he was convicted for second degree murder for his part in the rape and subsequent death [95] of Madge Oberholtzer. After Stephenson’s conviction in a sensational trial, the Klan declined dramatically in Indiana. Historian Leonard Moore concluded that a failure in leadership caused the Klan’s collapse:

Stephenson and the other salesmen and office seekers who maneuvered for control of Indiana’s Invisible Empire lacked both the ability and the desire to use the political system to carry out the Klan’s stated goals. They were uninterested in, or perhaps even unaware of, grass roots concerns within the movement. For them, the Klan had been nothing more than a means for gaining wealth and power. These marginal men had risen to the top of the hooded order because, until it became a political force, the Klan had never required strong, dedicated leadership. More established and experienced politicians who endorsed the Klan, or who pursued some of the interests of their Klan constituents, also accomplished little. Factionalism created one barrier, but many politicians had supported the Klan simply out of expedience. When charges of crime and corruption began to taint the movement, those concerned about their political futures had even less reason to work on the Klan’s behalf.:

I think we should cut the budget by $350 Billion next year by cutting the Defense and Homeland Security Budgets.

I think we should cut the budget by $350 Billion next year by cutting the Defense and Homeland Security Budgets.

If that were the correctg number it would seem insufficient that 40% of tax revenues is fair give back for more than 25% of total earned income. The earned income pie is far larger than the total taxes paid pot. if a box of a dozen donuts costs $3.00 and one guy puts up a $1.80 and then takes ten donuts I’d say he’s getting a far better share for his tax.

This proposal is somewhat similar to the one made in 2007 by Calvin Johnson (tax law professor @ Univ of Texas) published (in 117 Tax Notes 1082 (Dec 10, 2007, available on SSRN) to replace the 35 percent corporate tax on publicly traded companies with a 20-basis point quarterly tax on the issuer on the market capitalization including both traded debt and equity. The basic idea was to bypass all of the complexity (and finagling) involved in the measurement of taxable income of publicly traded corporations.)

Just a question. Can the author supply any countries that have taxed wealth over the past 100 years?

Generally we tax consumption and income, but not wealth. Property taxes are (sort of) an exception. The greater the value of the property, the higher the taxes.

I don’t mind if you tax my income. I don’t mind if you tax my consumption. But I will fight tooth and nail on taxing wealth. Whatever I have, I have already paid taxes on. You can’t tax it twice. If you do, all that wealth will just go where it is wanted. In other words, it will leave the country. Bad plan.

All that wealth may or may not hav e been taxed when it originated as income, though that may have been a good long time past and the growth of that wealth has gone untaxed since. In addition, that wealth may have first been taxed at favored rates, as in long term capital gain or estate taxes. Given that so much income at the upper margins escapes full taxation it would seem reasonable to tax the wealth as it accumulates. How is it, do you suppose, that that wealth is protected? Your friendly government spends an extraordinary amount of money protecting what you have. You pay a financial advisor 1%-1.5%, or more, to make the wealth grow. The 1% that would protect your wealth seems well spent, if not cheap.

bkrasting: “all that wealth will just go where it is wanted. In other words, it will leave the country.”

1. Did you not read the post? See “What about evasion and offshoring?”

2. Tax competition is right up there with arguments for tarrifs and trade restrictions on the list of zero-sum thinking.

Forgot the big one.. Government spending (and future spending of unknown, epic proportion) to subsidize and THEN bail out, mortages for people not nearly productive enough to have serviced them in the first place.

I would agree with this, except for one thing: the government *isn’t* spending much money on bailing out regular homedebtors. Witness the failure and recent demise of HAMP. It’s the BANKING SYSTEM that got bailed our to the tune of $Trillions (btw, TARP was but one small piece of the vast patch-work of bailouts).

Such a tax cannot possibly be proposed or enacted and even if it did America would be over.

You mean “America as it is currently constituted would be over.” And end to the current, hopelessly corrupt, rigged system would probably be welcomed by the bottom 80-90%, as it would mean an instant improvement in our relative political power and quality of life.