Not Enough to Shrink the Pay Gap with Other College Graduates

Teacher pay rises in 2023

by Sylvia Allegretto

Economic Policy Institute

Just offering up a portion of an EPI report on Teacher’s Earnings

Public school teachers attaining a bachelor’s degree to teach in the U.S. do not make similar wages as what other similarly degreed people in other fields. There is a pay gap between the disciplines and gender. The EPI report compares the pay of public-school teachers with the pay of college graduates working in other professions. The author is using BLS data to back their findings. This data is a the basis for Teacher pay rises in 2023.

Weekly Wage Trends

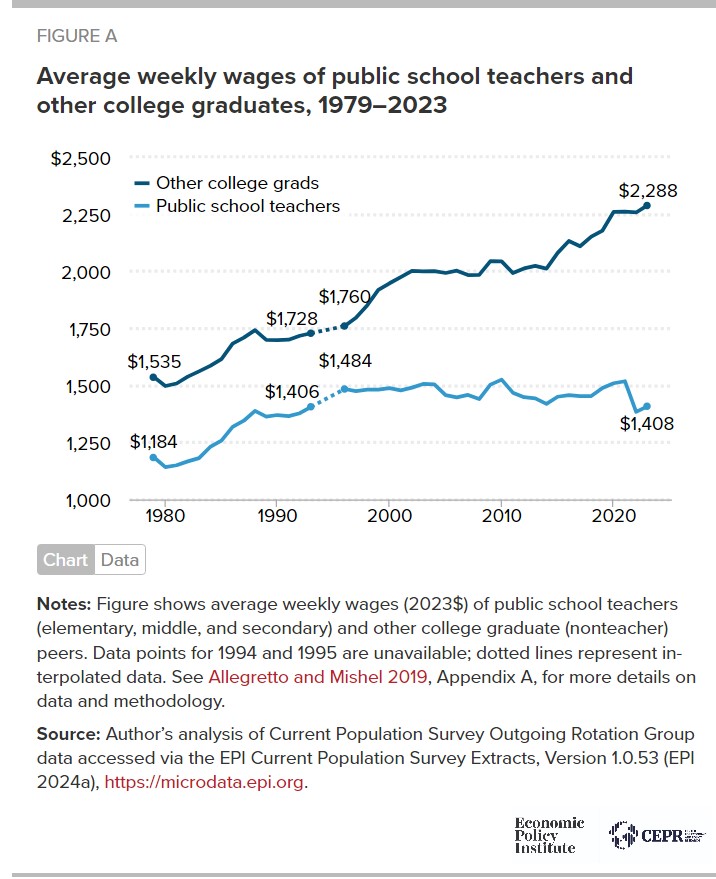

Shown in Figure A; Inflation-adjusted teacher wages were relatively flat from 1996 through 2021. This indicates teacher wages, on average, were just keeping up with inflation. This was also the case for the wages of other college graduates but for a shorter time span (2002–2014). After which for the latte, real increases ensued.

There was a small increase in teachers weekly wages of 1.7% ($24.00) in 2023. This was well belowthat need to match or exceed an 8.8% decline in 2022. It leaves the series of increases and decreases near a post-1996 low point. From 1996 through 2023, teacher wages fell by 5.1%. This was mostly due to a steep decline in weekly wages in 2022. In comparison, the wages of other college graduates increased 30.0% over the same timeframe. Wages increased significantly from 2014 onwards with a slight decline in 2022.

To stabilize the long-term stagnation and improve of teacher wages requires future increases in pay exceed future rates of inflation. This to recover the big loss in wages occurring in 2022 and keep up with future inflation. Political and community response and help by highlighting the severity of the issue would go a long way. The boosting of teacher pay requires a concerted effort by local and state governments along with support from the federal government.

Weekly Wages Relative to Other Disciplines

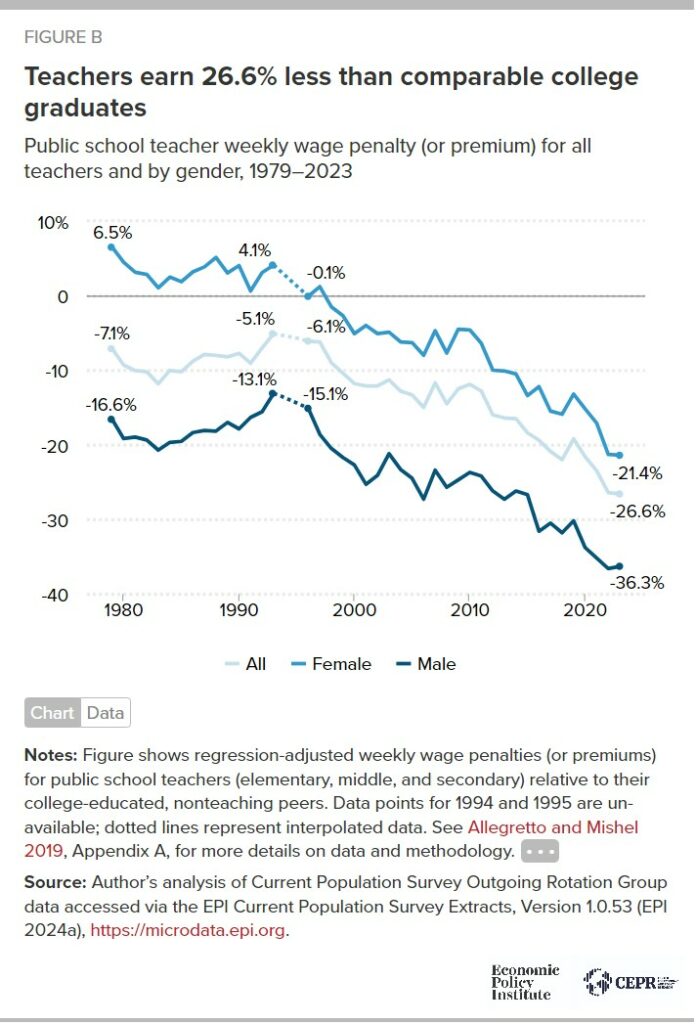

Figure B shows how much less (or more) teachers earn in weekly wages relative to other college graduates. This is estimated via regression analysis via the author. A weekly wage “penalty” for teachers is reported when the regression estimates suggest that teachers, all else equal, are paid less than other college graduates. A penalty appears as a negative number in Figure B. When teachers are paid relatively more, the number is positive and is referred to as a “premium.”

Starting in 1979 relative weekly wages for all teachers (faint graph line) lagged behind those of other similarly qualified professionals (middle line Figure B). Pre-1994, the teacher wage gap averaged 8.7%. The shortfall worsened considerably starting in the mid-1990s. The teaching penalty hit a record of 26.6% in 2023, and slightly worse than the penalty recorded in 2022 (26.4%). On average, teachers earned 73.4 cents on the dollar in 2023, compared with what similar college graduates earned working in other professions. This is also much less than the relative 93.9 cents on the dollar that teachers earned in 1996.

Figure B also shows the relative female teacher wage compared to other female professionals. Pre-1994, it was at a premium averaging 3.3%. Starting in 1996, the female wage gap quickly went from parity to a penalty, landing at a 21.4% penalty in 2023, slightly worse than the 21.3% gap estimated in 2022.

The author’s previous research (using decennial Census data) confirms over a longer timeframe, the relative wage estimates for female teachers moved from significant premiums to large penalties. For example, documented are relative female teacher earnings at a 14.7% premium in 1960, which lessened to 10.4% in 1970, and to near parity in 1980 (pre-1979 years not shown in Figure B). Using the estimates from 2023, the cumulative change has been a 36.1 percentage-point deterioration in the relative wage of female teachers since 1960.7

Declining Relative Wages

The important story behind the declining relative wages of female teachers? Historically, the teaching profession relied on a somewhat captive labor pool of educated women who had few employment opportunities. Thankfully this is no longer the case. Increased opportunity costs are a part of the story and reflected in much of this research.

Expanding opportunities enabled women to earn more as they entered occupations and professions from which they were once barred. Today, a much smaller share of educated women chooses the teaching profession over expanding opportunities with better pay. Simply maintaining the quality of the current labor market pool for teachers will require significant raises in real teachers’ pay to compete with other professions for female workers. Otherwise, the quality of education will be compromised.

The relative wages of male teachers have seen sizable penalties throughout the timeframe of this paper (1979–2023) and my analyses using 1960, 1970, and 1980 decennial Census data. Over the long run, the male penalty worsened from 20.5% in 1960 (not shown in Figure B) to 36.3% in 2023. The male teaching penalty persisting today goes a long way in explaining why men who could teach, may be compelled to pursue other career paths. Such paths which are on average are much more lucrative. The large male teacher penalty partly explains why approximately three in four teachers are women—a ratio that has not changed much since 1960.

There are also relative teacher wage penalties by state which is a following portion of his report.

One of the standard reviews of analyses I was involved in was to dig deep into sustained trends that were not the primary metrics. Metric B heads in a presumed negative way for 24 months, but primary metric A is not responding kind of situation. We don’t really care much about B, but it’s easy to measure and we presume it strongly impacts more important A as a kind of leading indicator. But is the presumption about B supported by the data? This trend on female teacher compensation is down 40+ years. But that is not a primary metric in education. For a trend to be sustained this long it probably should by now have produced clear evidence of negatively impacting more primary metrics like graduation rates, gpa, tests. Maybe relative pay is not really a strong variable in the education process. Or maybe it is but it’s steady-state control point is point is just not where the researchers expects it to be. I sympathize with the researcher here a little. “Similarly degreed” can be defined and then pretty easily measured, but it still leaves a sort of critical assumption that teachers and prospective teachers think of themselves in such a manner. Maybe they don’t, but defining what that might be and finding data about could be really hard.