Wage growth strongest for low-wage workers between 2019 and 2023

According to Word Press this article by EPI can be read in 7 minutes. It is not a difficult read and gives quite a bit of information.

Wage growth strongest for low-wage workers between 2019 and 2023

In this analysis, we divide the wage distribution into roughly five groups to uncover recent wage trends at different wage levels.

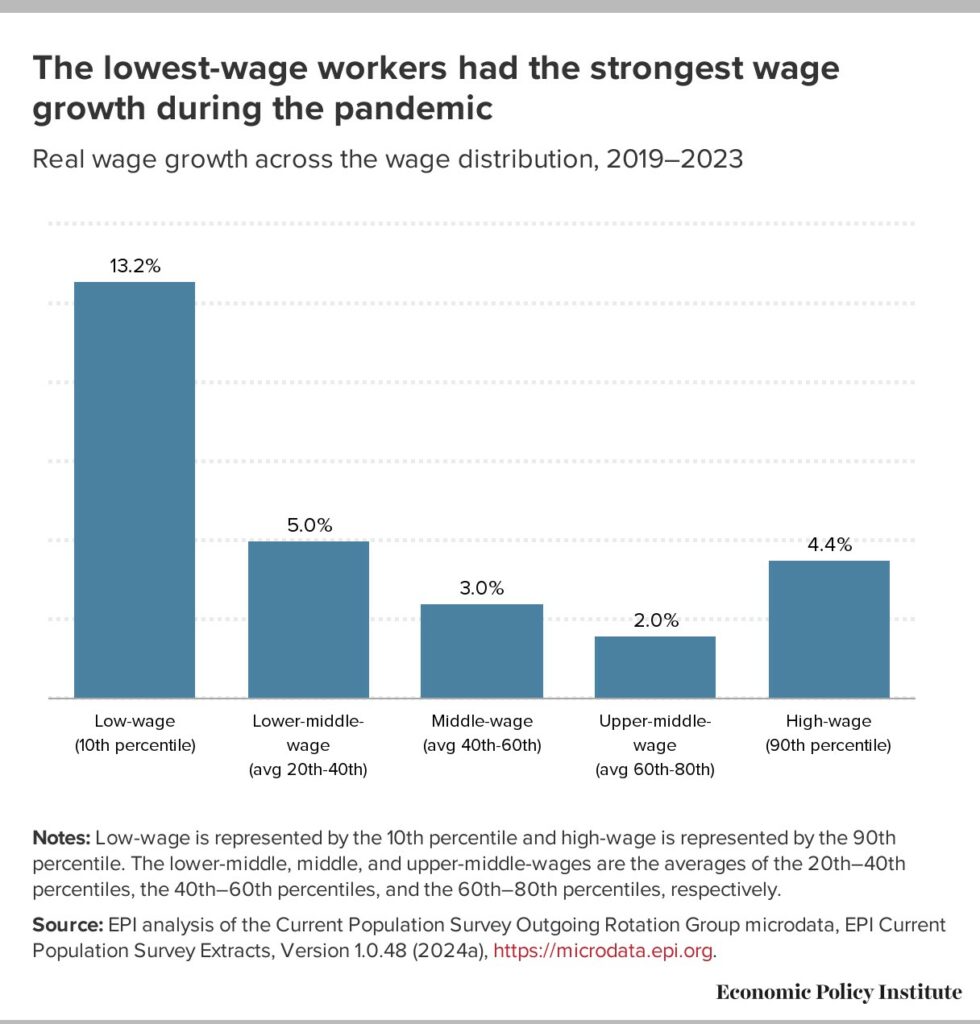

Figure A displays wage growth at the 10th percentile (“low-wage”), the average of the 20th–40th percentiles (“lower-middle-wage”), the average of the 40th–60th percentiles (“middle-wage”), the average of the 60th–80th percentiles (“upper-middle-wage”), and the 90th percentile (“high-wage”) using Current Population Survey (CPS) Outgoing Rotation Group microdata (EPI 2024a). Gould and deCourcy (2023) provide a more detailed discussion of these data measures and their robustness. Note that the 90th percentile as “high-wage” does not capture the earnings of those at the very top. This is better captured with other data sets which are discussed briefly later.

Our analysis focuses on changes in real wages between 2019 and 2023, as well as historical comparisons of real wage changes between 1979 and 2019. Our focus on 2019 and 2023 allows us to largely ignore the dramatic swings in employment and wages in 2020 and 2021, which were most impacted by the pandemic recession and initial recovery.

Real wage growth at the 10th percentile was exceptionally strong—even in the face of high inflation

Between 2019 and 2023, hourly wage growth was strongest at the bottom of the wage distribution. The 10th-percentile real hourly wage grew 13.2% over the four-year period. To be clear, these are real (inflation-adjusted) wage changes. Overall inflation grew nearly 20%, or about 4.5% annually, between 2019 and 2023. Even with this historically fast inflation, particularly in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic recession, low-end wages grew substantially faster than price growth. Nominal wages (i.e., not inflation-adjusted) rose by roughly 34% cumulatively since 2019.

Across the wage distribution, we see the pace of wage growth declining for each successive wage group until the 90th percentile. Compared with the 13.2% wage growth at the bottom, growth was less than half as fast for lower-middle-wage workers (5.0%) and less than one-third as fast for middle-wage workers (3.0%) between 2019 and 2023. Upper-middle wages grew 2.0% over the four-year period, while the 90th-percentile wage grew 4.4%.

Figure A

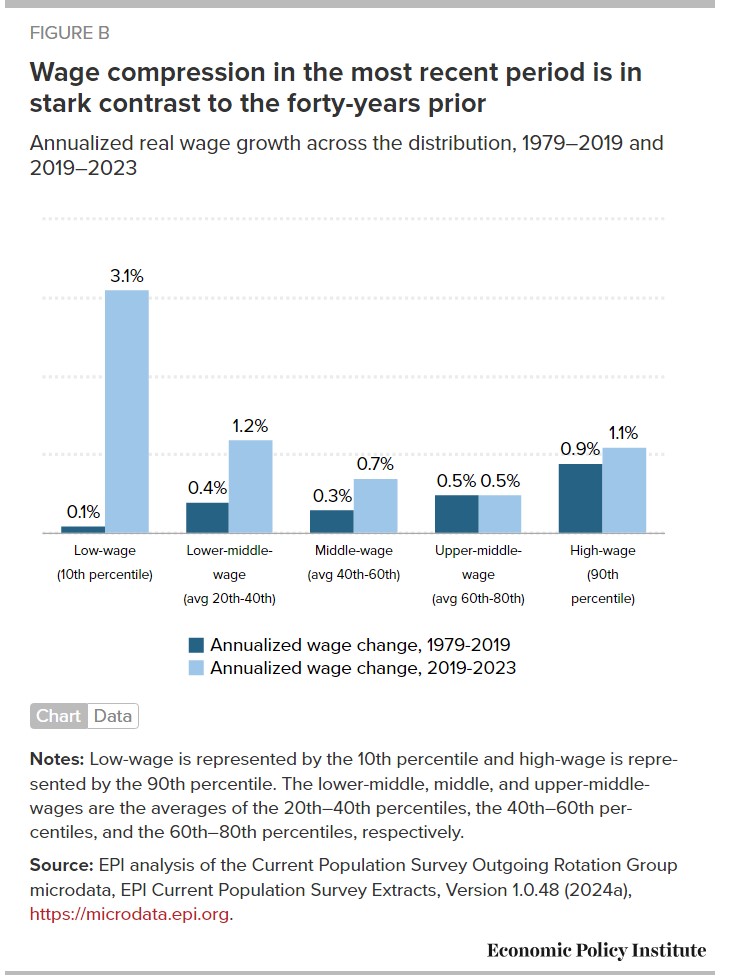

Wage compression in the most recent period contrasts sharply with prior 40 years

Because wages grew much faster at the 10th percentile than at the other four points, we measure within the 20th to 90th percentiles, wage compression has occurred. These findings (disproportionately strong wage growth at the bottom leading to wage compression) are consistent with the other research (see, for instance, Autor, Dube, and McGrew 2023).

This wage compression between 2019 and 2023 is in stark contrast with the experience of workers in the prior four decades. Figure B displays wage growth between 2019 and 2023 compared to wage growth between 1979 and 2019 for the same five wage groupings: low-wage, lower-middle-wage, middle-wage, upper-middle-wage, and high-wage. This time we report annualized wage changes in wages—which allow for comparison across periods which span different numbers of years, e.g. a four-year span versus a forty-year span.

The differences in wage growth between these periods are striking. Whereas in the most recent period wage growth was stronger among each successive lower wage group starting with upper-middle-wage workers on down, the opposite pattern occurs in the earlier forty-year period. Each successive higher wage group displays wage growth at least as fast as the previous one, except for between the lower-middle to the middle-wage group where there’s a small decrease. In the most recent period, middle-wage workers experience growth nearly two-thirds (63.6%) as fast as high wage workers.

In the 1979-2019 period their wage growth was one-third as fast. The difference is even more extreme for the lowest wage workers: close to zero growth over the forty-year period versus more than 3% annualized growth over the past four years. All wage groups experienced wage growth at least as fast in the most recent period as between 1979 and 2019, and much faster among roughly the bottom half of the wage distribution.

The very top continues to amass larger shares of the overall pie

Changes at the very top of the wage distribution cannot be measured using the CPS. Social Security Administration (SSA) data reveals what’s happening within the top 10%, 5%, 1%, and even 0.1% of the annual earnings distribution. Between 1979 and 2019, the bottom 90% grew 0.6% on an annualized basis, while the top 5% grew 2.0% and the top 0.1% grew 3.8% (Gould and Kandra 2023). There are vast differences not only between the top and the vast majority, but also within the top of the earnings distribution.

The latest SSA data only extends to 2022. The 2019–2022 period is characterized by relatively even growth. This is primarily because stock market declines in 2022 drove losses among the highest earners. After dropping significantly in 2022, the stock market rebounded greatly in 2023 (Trackinsight 2024). Therefore, very top earnings are likely to show a solid rebound in 2023, continuing the concentration of wages at the high end.

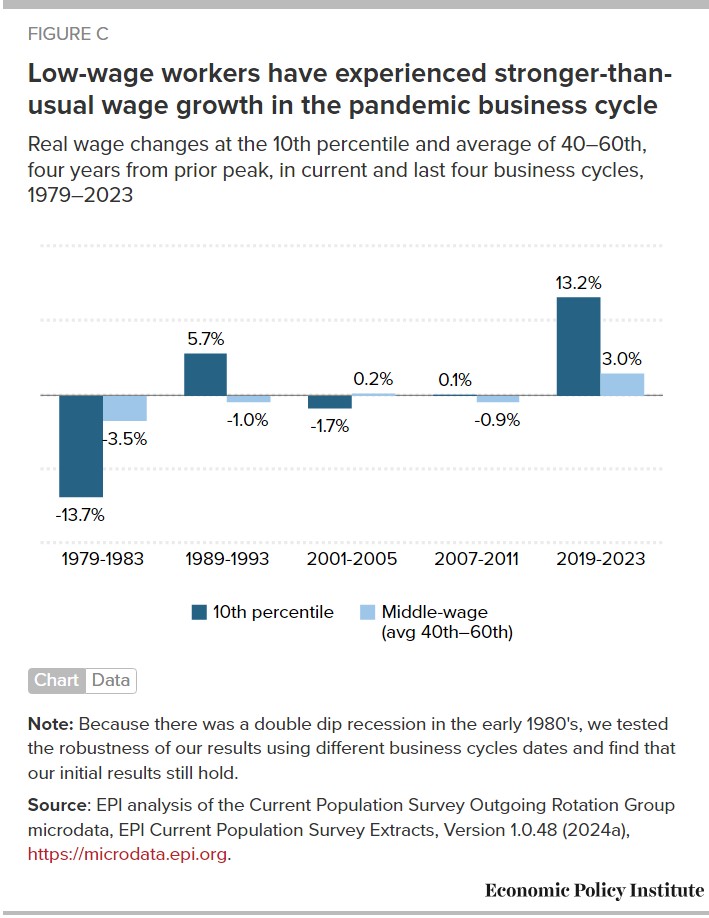

The bounce back low-wage workers experienced was stronger than in any business cycle since 1979 Smart policy was a key factor

Figure C shows just how exceptional this recovery has been in achieving strong wage growth for low-wage workers. The figure presents the real changes in the 10th-percentile wage and the middle wage four years from the prior peak in each business cycle since 1979. Wage growth at the 10th percentile in the current business cycle is more than twice as fast as the next closest period over the last 40 years.

Middle-wage workers—workers between the 40th and 60th percentiles of the wage distribution—experienced slower gains in the recent business cycle compared to low-wage workers. However, the slower middle-wage growth over the last four years was significantly faster than that found in the four prior business cycles.

Faster growth for low-wage workers were occurring due to policy decisions and a tight labor market

The fast growth over the last four years, particularly for low-wage workers, didn’t happen by luck: It was largely the result of intentional policy decisions that addressed the pandemic and subsequent recession at the scale of the problem. Policymakers learned from the aftermath of the Great Recession, in which the pursuit of austerity led to a slow and prolonged economic recovery.

Several large spending bills were passed in the first year of the pandemic. The bills provided enhanced and expanded unemployment insurance, economic impact payments, aid to states and localities, child tax credits, and temporary protection from eviction, among other measures (Gould and Shierholz 2022). These actions provided relief to workers and their families to help them weather the recession. These measures also fed the surge in employment, which gave low-wage workers better job opportunities and leverage to see strong wage growth.

Unemployment fell to 3.6% in 2022 and held steady in 2023 as both the labor force and employment grew. The share of the population ages 25-54 with a job—the prime-working-age employment to population ratio (EPOP)—rose to 80.7% in 2023, surpassing even the pre-pandemic high of 80.0% in 2019. In fact, we have to go back to 2000 to find a prime-working-age EPOP that exceeds the level reached in 2023.

This tightening labor market further bolstered workers’ leverage. Low unemployment means that workers are relatively scarce, which requires employers to work harder to attract and retain workers and lessens their discretion to discriminate without facing a profitability penalty. In low-unemployment labor markets, lower-wage and historically marginalized workers experience better labor market outcomes and faster wage growth (Bivens and Zipperer 2018; Wilson and Darity 2022).

In addition, the sudden loss of millions of low-wage jobs at the start of the pandemic, followed by the extraordinarily fast employment recovery, meant that the frictions that tie workers to particular jobs—that is, the barriers that would normally keep workers from searching for better employment opportunities—were not constraining workers looking for work in this period. This “severed monopsony” in a time of furious re-hiring reduced the normal drag on wage growth imposed by these frictions (Bivens 2023). High numbers of low-wage workers quit and found better jobs, increasing churn in the low-wage labor market. This phenomenon increased low-wage workers’ leverage, which further contributed to faster wage growth. Employers simply had to work harder to attract and retain the workers they wanted.