The Cost of Delivering Rural Emergency Department Services

This is the boring stuff on healthcare. How to consider the costs of a rural emergency department care in a small rural hospital when it is not in constant use? And what happens when the population is small and the costs equal or exceed the funds taken in by its operation. The article provides a good foundation portraying those costs.

The article suggests rural hospitals suffer greatly from the same amount of payment as what may be experienced in much larger communities. Those payments coming from commercial healthcare insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, and the VA. The cost base is greater or the same and the revenue is less, giving less room to cover costs.

Saving Rural Hospitals Part 2

by Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform

The single most essential service that rural hospitals provide is a 24/7 Emergency Department. Although emergency departments at small rural hospitals do not have the capability to treat severe trauma cases and emergencies requiring highly-specialized services, neither do many urban hospital EDs. The primary roles all EDs perform are to quickly and accurately diagnose health problems, provide any necessary treatment to the patients, and transfer the small set of patients who need specialized care to a trauma center, stroke center, etc. Residents of rural communities who do not have access to an Emergency Department may be more likely to die or experience complications that could have been prevented.

This section will examine the costs involved in operating Emergency Departments at small, rural hospitals. The focus in this section will be on the basic ED visit itself, not on any additional services a patient may receive during the visit that are delivered by other hospital departments, such as a laboratory test or an imaging study. The costs of delivering those other services will be examined separately below.

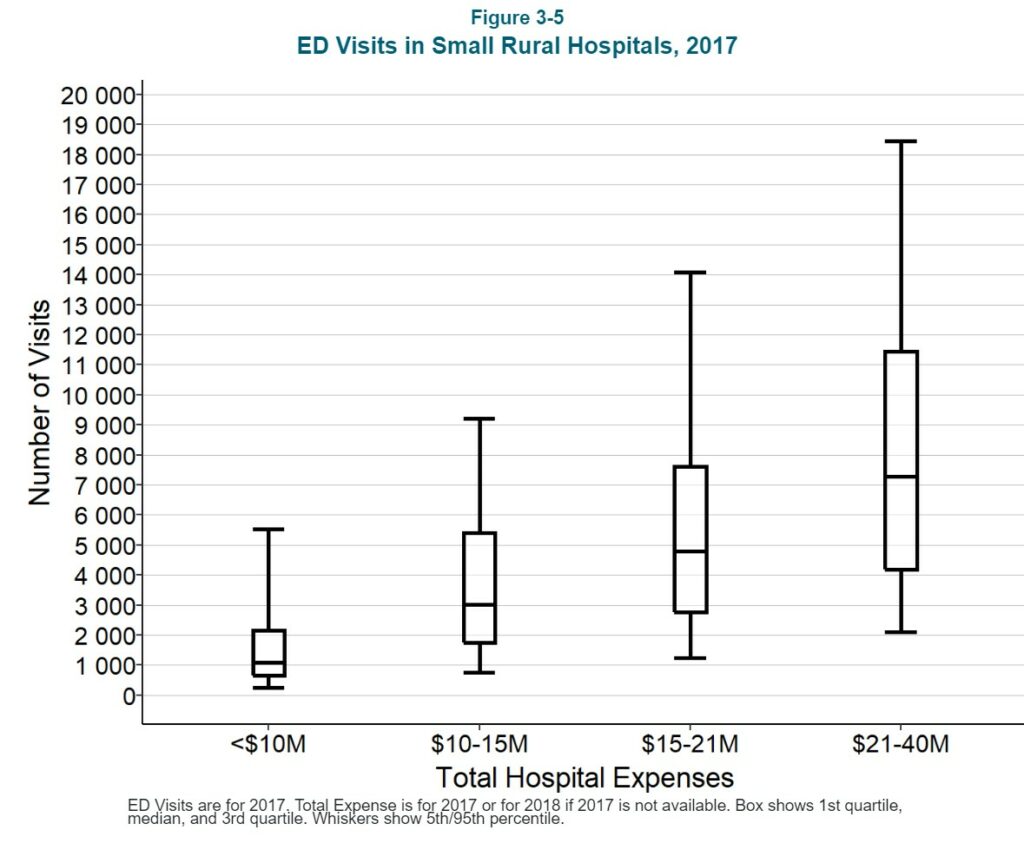

The Number of ED Visits at Small Rural Hospitals

It is reasonable to expect that the cost of an Emergency Department will depend on how many visits the ED has. Rural hospitals that have a small number of inpatient admissions seem less small when one counts ED visits. The majority of small rural hospitals had fewer than 5,000 ED visits in 2017, i.e., about one visit every 2 hours.1 However, there is also considerable variation in the volume of ED visits among these hospitals; 10% of small rural hospitals (i.e., hospitals with less than $30 million per year in total expenses) had more than 11,000 ED visits in 2017, while another 10% had fewer than 1,000 visits.

The large variation in the number of visits is due to a variety of factors, including the size of the community the hospital serves, the age and health status of the residents in the community, the number of businesses and workers in the community, the number of tourists who visit the community, and the community’s proximity to an interstate highway. Importantly, the number of ED visits will also depend on the availability of primary care in the community. For example, a hospital with no Rural Health Clinic will likely have more ED visits than a hospital that has an RHC because, without easy access to a primary care practice, more residents of the community will need to use the ED for non-emergency care.

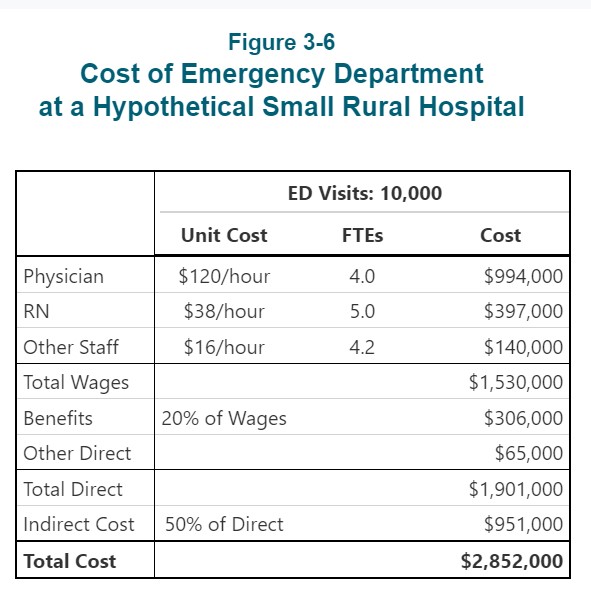

The Cost of Operating an ED With 10,000 Visits Per Year

Each hospital’s cost report includes information on the total cost of operating its emergency department, but it is impossible to determine why some EDs are more expensive than others, even with the same number of visits, because there is very little information on the individual components of that cost. In particular, personnel costs would be expected to be the single largest component of the cost of an ED, but there is no information available on the number of physicians, nurses, or other staff who work in the ED, the number of hours they work, or the wage rates they are paid.2

However, since the ED needs to deliver high-quality care to patients who come with a wide range of problems at unpredictable times, one can estimate the level of staffing that a hospital would likely need in order to provide that care and how the staffing would change based on the volume of ED visits the ED receives.

Physician Staffing

An Emergency Department that has 10,000 visits per year will see an average of one new patient every hour. Although not every patient who comes to the ED will need to see a physician, the ED will need to have a physician available in case they do, so there will have to be at least one physician on duty at all times.3

The volume of visits will generally be higher at certain times of the day, days of the week, and months of the year. For example, hospitals in communities with a large number of seasonal businesses, such as those in agriculture and tourism, will have higher volumes of ED visits during some months than others. However, since productivity standards for Emergency Departments generally assume that an ED physician can manage 2-3 visits per hour, it will generally not be necessary for an ED with 10,000 visits per year to have any more than one physician on duty at a time except during exceptional circumstances.4

However, since the ED is a 24/7 operation, the hospital will have to employ or contract with at least 4 full-time equivalent (FTE) physicians in order to have one physician in the ED at all times.5 (The exact number of physicians will depend on the number of shifts each physician is willing and able to work each week, the amount of time the physicians need to spend in continuing education, vacation days, etc. Some rural hospitals have to hire or contract with multiple physicians, each of whom come to the community for a short period of time, in order to have one “full-time equivalent physician.)” 6

A hypothetical hospital that employs 4 FTE physicians to staff its ED will need to spend about $1.2 million to do so if it pays the physicians a salary of $120/hour with benefits equivalent to 20% of the salary. However, the actual cost of employing emergency physicians can vary significantly from community to community and from year to year depending on a hospital’s ability to attract and retain physicians.

If a physician retires or resigns, a hospital will often need to hire a temporary physician to fill in while a permanent replacement is found, and the hourly cost of the temporary physician will generally be significantly higher than the cost of a permanent employee. Many rural hospitals contract with national ED staffing companies in order to eliminate the burden of maintaining a full staffing complement and to make the cost of staffing the ED more predictable7, but this can increase the overall cost of the ED because the staffing company has to be paid more than the physicians themselves receive.

Nursing Staff

In addition to a physician, the ED will also need at least one Registered Nurse (RN) around the clock to help in triaging, treating, and discharging patients. Since a nurse will generally need to spend more time with each patient than the physician does, it is possible that one nurse will be insufficient if multiple patients come to the ED at the same time or if the patients have more serious conditions. Small rural hospitals will typically deal with multiple visits or more serious cases by having a nurse from the inpatient unit come to the ED to provide assistance. (The need for this backup coverage will affect the nurse staffing levels the hospital will need in the inpatient unit, as discussed in a later section.) If the higher volumes occur at predictable times, the hospital may need to have two nurses on those shifts.

In order to have at least one nurse in the ED at all times, a hospital will have to employ as many as 5 FTE RNs.8 If the hypothetical hospital pays RNs $38/hour and provides benefits equal to 20% of salary, the total cost for the year will be more than $400,000. Here again, though, the cost of employing nursing staff will vary across communities and over time based on the ability of individual hospitals to attract and retain nurses and how much it costs them to fill vacancies temporarily while permanent replacements are being recruited.

Other Staff

The hospital will likely also need at least one non-clinical staff member to check patients in, help family members, etc. so that the physician and nurses can focus on providing clinical services to the patients. In order to have such a staff member in the ED at all times, the hospital will need to employ 4-5 FTEs. Assuming a $16/hour wage and 20% benefits, this will cost the hypothetical hospital an additional $170,000 per year.

Other Direct Costs

Almost all of the direct costs of operating an Emergency Department are associated with the physicians, nurses, and other staff. The costs of any medications used and other supplies that are billed to a patient separately are ordinarily assigned to a separate hospital cost center (these costs will be discussed separately in a later section), so non-personnel direct costs for the ED itself will generally be relatively small.

Indirect Costs

Finally, the operation of the ED also depends on the hospital providing space and utilities, maintenance for equipment, housekeeping, billing for patient visits, payroll and benefits for staff, medical records, etc. Consequently, a portion of the hospital’s costs for those activities must be allocated to the ED to properly represent the total cost of operating the ED. Typically, these indirect costs increase the total cost of an ED by about 50% beyond the personnel and other direct costs discussed above.9

Total Cost

These five components together imply that it will likely cost the hypothetical hospital nearly $3 million to deliver services to 10,000 ED patients during the year.

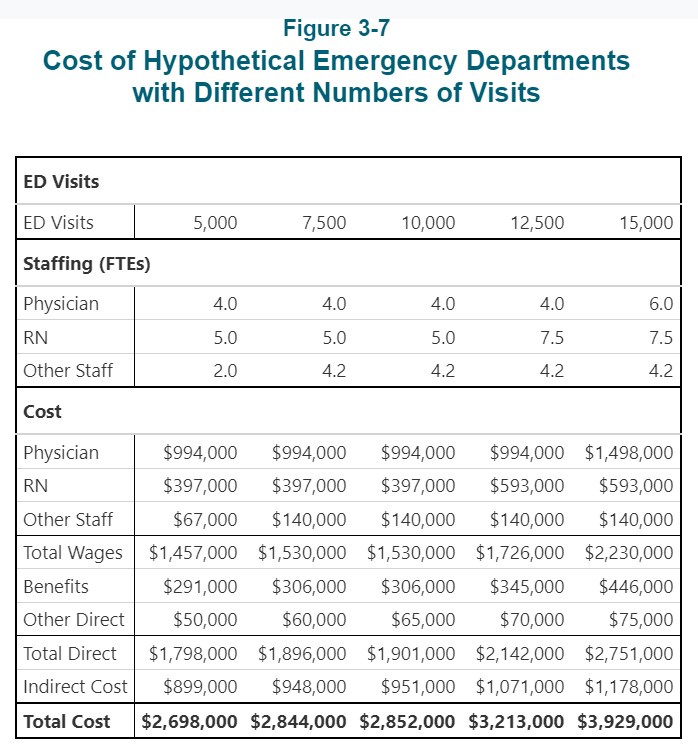

The Cost of Operating an ED with More or Fewer Visits Per Year

How does the cost differ for an ED with more or fewer visits?

- For a hospital ED with 7,500 visits per year (i.e., 25% fewer than the 10,000 visits discussed above), there will still be almost one visit every hour, so this ED will also need one physician, one nurse, and a third staff member on duty round the clock. Other direct costs will be slightly lower with fewer patients and the indirect costs assigned to the ED may also be lower. Using the same assumptions about wage and benefit rates as for the hypothetical hospital discussed above, the total cost of the ED will be 96%-97% of the cost of the 10,000 visit ED, even though there are 25% fewer visits.

- Even if a hospital ED has only 5,000 visits per year, it will generally need to have a physician and nurse on duty around the clock, since it would have more than one visit every two hours on average. It is possible that the ED might be able to avoid using a third, non-clinical staff member during certain times of the day or week when the volume of visits is low, particularly if there is someone working in a different department at the hospital who can perform the same functions when needed, but this would only reduce the personnel costs by a relatively small amount. The total cost of an ED this size would likely still be more than 90% as much as the cost of the 7,500-visit ED, even though there are 33% fewer visits.

- If the ED has 12,500 visits per year (25% more than the 10,000 visits at the hypothetical hospital discussed earlier), it will have an average of 1.5 visits per hour, which can also generally be managed with a single physician on duty. However, because of the greater potential for delays during peak times, a hospital may choose to have an additional nurse on some shifts, which will increase the total number of nurses needed to staff the ED overall. As a result, direct costs and indirect costs may be 13% higher than at the ED with 10,000 visits.

- If the ED has 15,000 visits per year (50% more than the 10,000 visit ED), it will have an average of nearly 2 visits every hour. Because ED visits do not occur at a constant rate throughout the day and week, it is likely that the ED will have more than 3 visits per hour during its busiest times, which is more than a single physician can safely handle. Consequently, the hospital will likely need to hire additional physicians in order to have two physicians on duty during the high-volume shifts, in addition to a larger number of nurses. This would increase the cost of operating the ED by 45% over the cost at the 10,000 visit level, although this increase is still smaller than the 50% increase in visits.

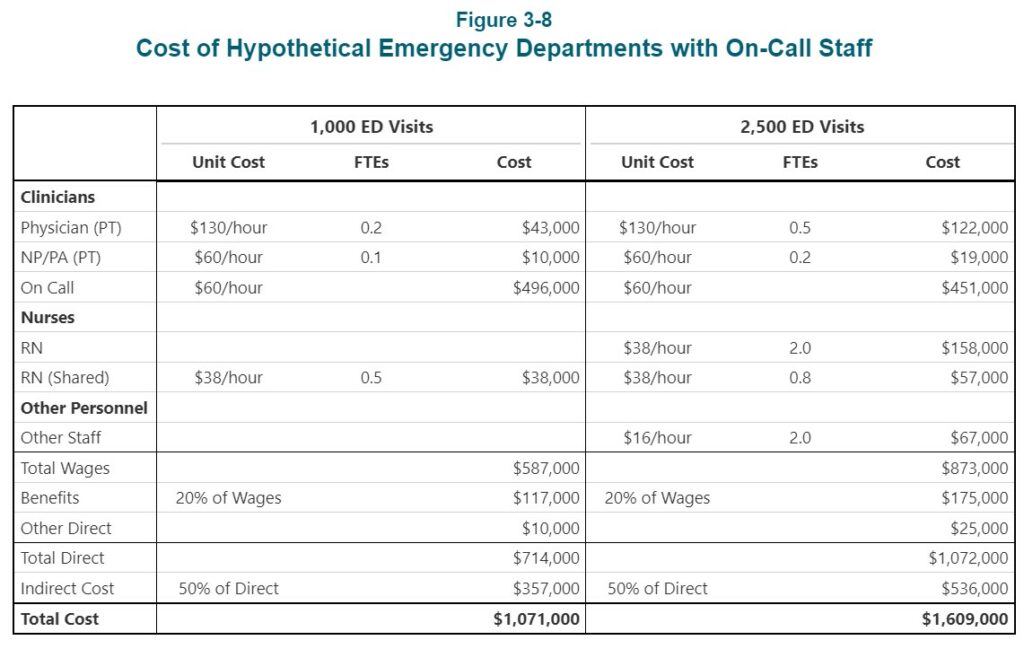

The Cost of Operating an ED with Even Fewer Visits

Most small rural hospitals have fewer than 5,000 ED visits per year. If the number of visits is less than about 10 per day (i.e., less than one visit every 2-3 hours), the hospital may be able to staff the ED differently, at least during some shifts. However, its ability to do so will depend on what other services the hospital offers, the availability of other physicians in the community and their willingness to help staff the ED, and the availability of remote support services from larger hospitals:

- If the hospital operates a Rural Health Clinic in or next to the facility where the ED is located, the physicians, nurse practitioners, or physician assistants who work in the clinic could leave the clinic and go to the ED to see a patient who comes to the ED during normal clinic hours.10

- At a hospital with a Rural Health Clinic(RHC), the RHC physicians/clinicians could also provide on-call coverage during night or weekend shifts when visit volumes are lower. If there are other primary care physicians in the community, they may also be willing to provide on-call coverage for the ED.

- A very low-volume ED could potentially use emergency-trained nurses to staff the ED if the hospital can arrange for telemedicine support from emergency physicians at a larger hospital.11

- If the nursing staff in the hospital’s inpatient unit is large enough (e.g., because the hospital has a large number of swing-bed patients), if the inpatient unit is close enough to the ED, and if the volume of ED visits is low enough, the hospital could rely on the inpatient unit nurses to staff the ED when a patient arrives, either during some shifts or all shifts, rather than having a nurse assigned exclusively to the ED.

The table below shows what the cost might be to operate a hypothetical ED that has 1,000 visits per year. This represents an average of fewer than 3 visits per day or less than one visit every 8 hours. The hospital where this ED is located is assumed to also operate a Rural Health Clinic staffed by both a physician and a Nurse Practitioner (NP). The physician and the NP take responsibility for seeing patients who come to the ED during clinic hours.

In addition, the Rural Health Clinic clinicians and one or more other physicians in the community are assumed to be willing to contract with the hospital to provide on-call support, i.e.. They would agree to come to the ED quickly if and when a patient arrives. The example also assumes that there would be no dedicated nurses in the ED, and that one of the nurses from the hospital’s inpatient unit would go to the ED when a patient arrives. The total cost of this arrangement is just over $1 million. This is still about 40% of the cost of the ED with 10,000 visits, even though there are only one-tenth as many visits.

A hospital with 2,500 visits per year (about 6 visits per day) might still be able to rely on physicians at the Rural Health Clinic and in the community to diagnose and treat patients. However, it would be more problematic to rely solely on nurses from the inpatient unit to staff the ED, particularly during busier times, so it might need to employ additional nurses for this purpose. As shown in the table, the total cost might be about $1.6 million.

Next up? Total Service Line Costs and is payment adequate to cover smaller and rural hospitals?