Income Uncertainty and ACA marketplace Application

by Andrew Sprung

xpostfactoid

Brian Blase, a conservative healthcare scholar at the Paragon Institute, is out with an analysis of 2024 ACA marketplace enrollment (summarized in this WSJ op-ed) claiming that millions of enrollees have mis-estimated their incomes to claim benefits to which they are “not entitled.” Here are the core claims:

In nine states (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Utah), the number of sign-ups reporting income between 100 percent and 150 percent FPL exceed the number of potential enrollees. The problem is particularly acute in Florida, where we estimate there are four times as many enrollees reporting income in that range as meet legal requirements.

The problem of fraudulent exchange enrollment is much more severe in states that have not adopted the ACA’s Medicaid expansion as well as in states that use the federal exchange (HealthCare.gov). In states that use HealthCare.gov, 8.7 million sign-ups reported enrollment between 100 percent and 150 percent FPL compared to only 5.1 million people likely eligible for such coverage, or 1.7 sign-ups for every eligible person….

Unscrupulous brokers are certainly contributing to fraudulent enrollment and the enhanced direct enrollment feature of HealthCare.gov appears to be a problem. Brokers just need a person’s name, date of birth, and address to enroll them in coverage, and reports indicate that many people have been recently removed from their plan and enrolled in another plan by brokers who earn commissions by doing so.

Blase’s core conclusions — that benefits generous enough to induce the uninsured to access them should be scaled back, and that efforts to streamline enrollment should be broadly rejected — are unwarranted, as argued below. His use of the term “fraud” is overbroad. But he does point to weaknesses in enrollment security and incentives to agent malfeasance that are reflected in enrollment data and need to be addressed.

First, the ability of agents to access existing accounts or create new ones without verifiable enrollee consent, coupled with subsidy boosts enacted in March 2021 that rendered additional millions eligible for free coverage, has opened an avenue for fraud that’s been exploited in probably hundreds of thousands (not millions) of accounts in the 32 states using the federal exchange, HealthCare.gov. CMS must shut down the fraud, and quickly — working with agents, state insurance departments, insurers and commercial web-brokers — as well as implementing a tech fix (I have written about the agent/broker scandal and proposed solutions here, here, here, and here.).

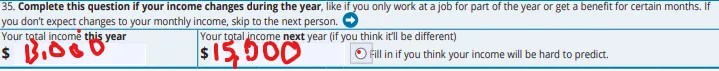

Second, agents and to some extent nonprofit assisters doubtless do lead some enrollees to massage their income estimates, and, as Blase avers, they have since the marketplace’s launch in the fall prior to Plan Year 2014. That’s inevitable in a system that 1) bases benefits on future income projections, 2) mainly serves low-income people, whose income often fluctuates and is hard to predict, and 3) includes income break points where benefits change substantially — including, most radically, whether benefits are available at all, i.e., the 100% FPL minimum income requirement in states that have refused to enact the ACA Medicaid expansion. As more agents have piled into the market (there were 83,000 registered with HealthCare.gov in 2024, up from 49,000 in 2018), projected income massaging may have increased, though CMS data breaking out enrollment by income doesn’t unequivocally support that conclusion (more on that below).

Third, at least one part of one administrative rule designed to reduce enrollment friction and reduce the uninsured rate, implemented after subsidies were expanded in March 2021, has doubtless stimulated unauthorized (and fraudulent) plan-switching by agents. In early 2022, CMS introduced a continuous Special Enrollment Period (SEP) — effectively year-round enrollment — for applicants with income below 150% FPL, who, thanks to the ARPA subsidy increases, by that point had access to a benchmark silver plan for zero premium. That’s in the spirit of year-round Medicaid enrollment, as the 150% FPL threshold isn’t much higher than the 138% FPL Medicaid eligibility threshold in nonexpansion states. The problem is not with enabling the low-income uninsured to get coverage year-round, but with allowing a monthly SEP that enables monthly plan-switching. That’s what rogue brokers have exploited.

That said, Blase almost certainly exaggerates the extent of enrollment fraud and draws mostly wrong conclusions from it. CMS should be able to get a handle on unauthorized agent-executed plan-switching and enrollment. The 19 state-based marketplaces (SBMs) seem to have mostly prevented it. Probably at some cost to enrollment growth. CMS will be trying to strike a balance, adopting some requirement that an agent show proof of enrollee consent that generates less friction than do SBM security measures (e.g., requiring two-factor authorization from the client).

An outbreak of preventable agent fraud should not compromise or legislatively endanger extension of the enhanced premium subsidies temporarily enacted in the American Rescue Plan’ Which such have brought the Affordable Care Act within striking distance of living up to its name. Those enhanced subsidies were extended through 2025 by the Inflation Reduction Act but will expire if not further extended. Erasing zero-premium coverage at low incomes would mean erasing coverage gains that have been a boon to millions of low-income enrollees.

It should be noted that much if not most of the impetus for agent fraud — plan-switching and enrollment not authorized by the enrollee — would disappear if ten states were not stubbornly holding out against the interests of their people, their hospitals and their finances by refusing to enact the ACA Medicaid expansion. In non expansion states, eligibility for marketplace subsidies begins at 100% FPL, rather than at the 138% FPL Medicaid eligibility threshold in effect in expansion states.

Non expansion has created a huge pool of enrollees who project income in the 100-138% FPL range. People at or near poverty belong in Medicaid, which is a simpler, more affordable (with near-zero out-of-pocket costs) and more cost-effective benefit than marketplace coverage. If those states all enacted the expansion tomorrow, more than 6 million of the 9.4 million marketplace enrollees who estimated income below 150% FPL (qualifying them for free benchmark silver coverage) would transition to Medicaid — radically shrinking the marketplace in those states and changing incentives for the large call centers that have been targeting low-income marketplace enrollees. But that rapid Medicaid expansion is not going to happen.