Two years after the end of Roe v. Wade, most women on probation and parole have to ask permission to travel for abortion care

Since the 2022 Dobbs decision, 21 states have restricted abortions earlier than the Roe v. Wade standard. Now, more of the 800,000 women on probation and parole must seek abortion care out-of-state — but for many, whether they can get there depends on an officer’s decision.

by Wendy Sawyer

Blog | Prison Policy Initiative June 18, 2024

June 24 marks two years since the Supreme Court stripped Americans of their constitutional right to abortion. The court’s 2022 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization permitted state governments to limit and even ban abortion care — and they did. As a result, the share of patients who cross state lines for abortion care has almost doubled, from about 1 in 10 to almost 1 in 5. Traveling out-of-state for health care, including abortions, is a hardship for anyone, but it is especially challenging for people on probation or parole.

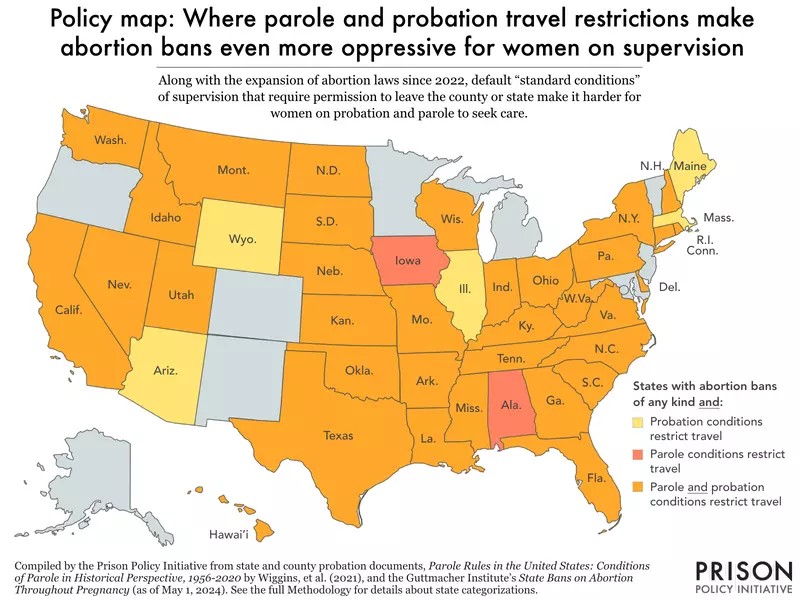

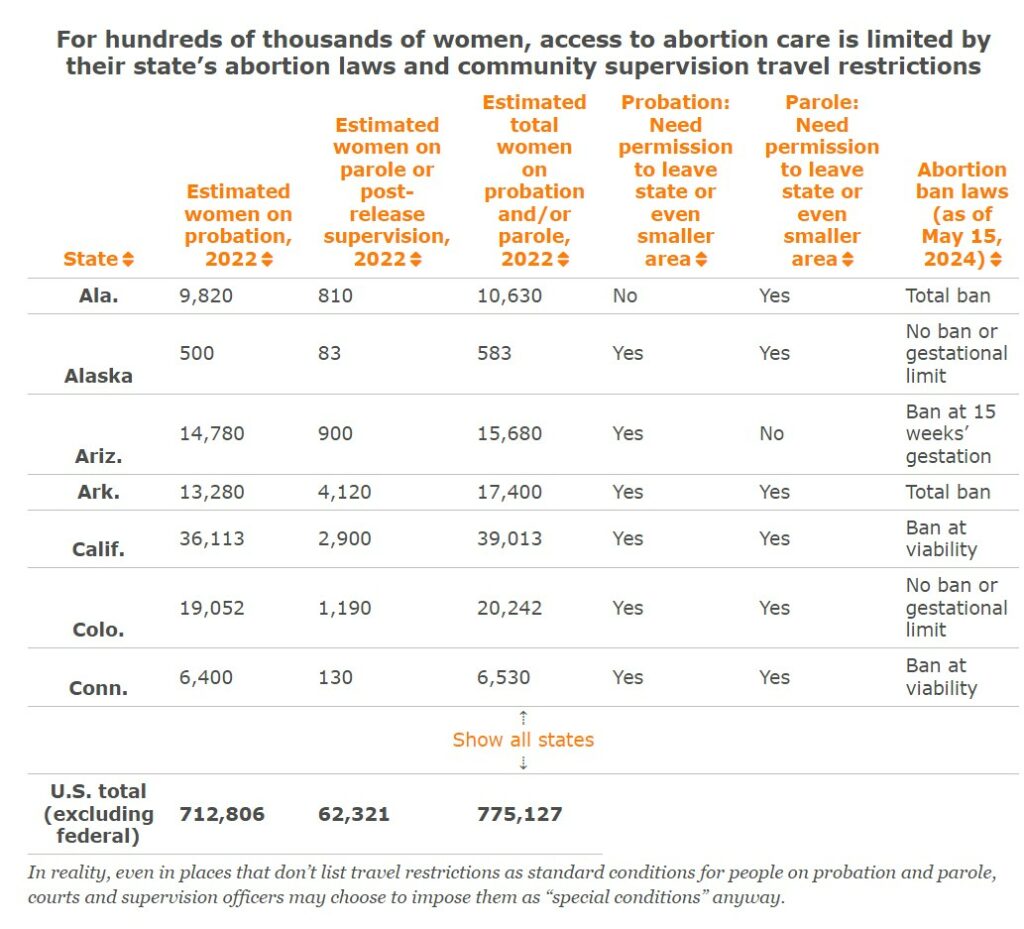

According to The New York Times, since the Dobbs decision, 21 states have implemented abortion rules more restrictive than the standard under Roe v. Wade. Fourteen states now ban abortion altogether, and most other states ban abortion after a certain point in pregnancy. And while some of these less-restrictive bans preserve abortion as an option for most people who need one, these bans are nonetheless as obstructive for people who need abortion care after their state’s time limit. In all, 41 states have some kind of abortion ban in place post-Dobbs, whether “total bans” or bans based on gestational duration. In every one of these states, standard conditions of probation and/or parole require permission to travel out of state, county, or another specified

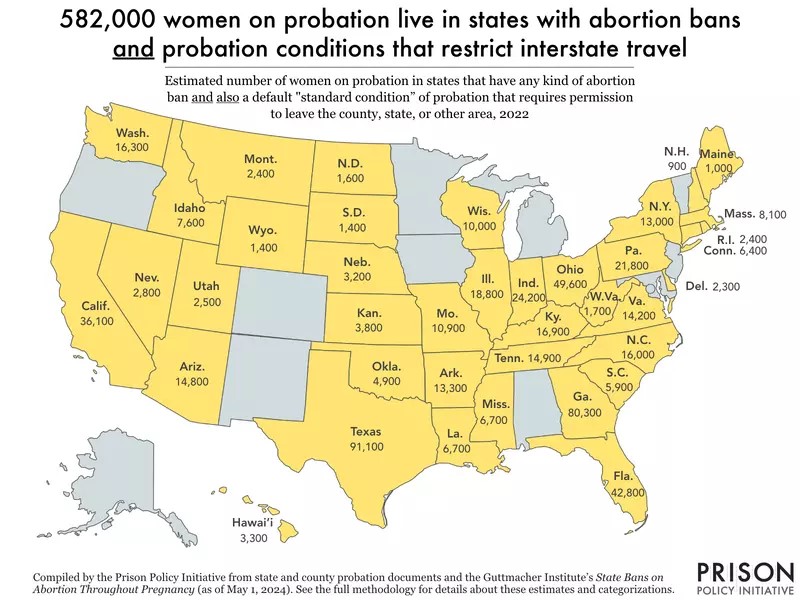

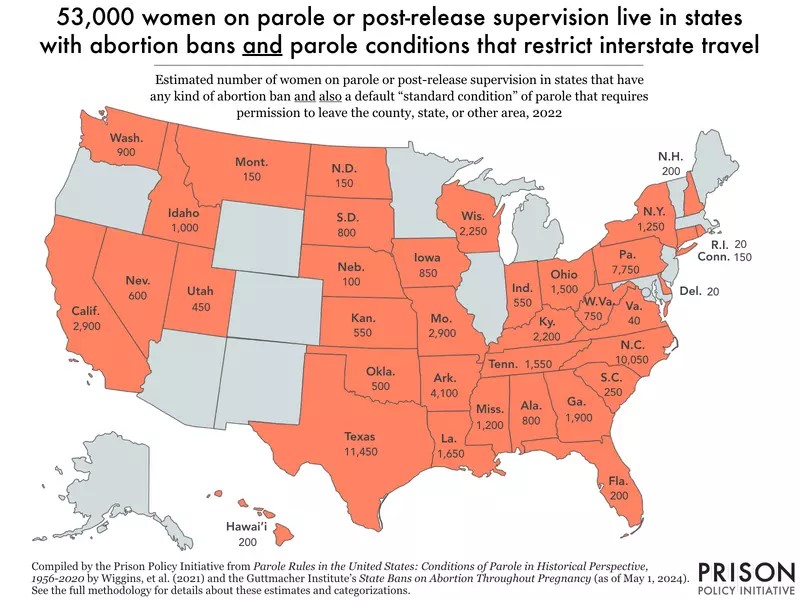

To understand how this post-Dobbs landscape impacts women under the U.S.’ massive system of community supervision, we examined standard supervision conditions in each state, along with the number of women who must comply with them. We find that the one-two punch of abortion and supervision restrictions impacts an estimated 4 out of 5 women (82%) on probation or parole nationwide. It means for the vast majority of people under community supervision, the ability to seek abortion care out-of-state is the states decision. It is left to the discretion of a correctional authority, typically their probation or parole officer.

Specifically, we find that, excluding federal probation and post-release supervision, 82% of women on probation and 85% of women on parole live in states that (1) either completely ban abortion or restrict it based on gestational age and (2) list travel restrictions as a standard condition of supervision.

Every state and D.C. restrict the movement of people on probation or parole. For our analysis, we first looked at rules related to travel in the standard conditions of probation and parole in each state and D.C. (These are summarized in the table below.) We find that probation agencies in all but two states (Ala. and Iowa) generally require permission to leave the state, county, or other designated area. Four of these states empower the court or probation officer to set the boundaries for travel restrictions on an individual basis. Rules restricting interstate travel are just as common in the context of parole and post-release supervision: 40 states have a standard condition requiring permission to leave the state. Among the states that do not, five (Ark., Iowa, Mont., N.M., and Pa.) require permission to leave an even smaller area — the county or district. West Virginia and D.C. require permission to travel, but individualize the specific geographic boundaries in the supervision contract.

Excluding federal supervised populations, the vast majority of women on probation (98% or 672,000) and parole (96% or 60,000) live in states where their standard supervision conditions require permission to leave the state, if not an even smaller geographic area. Every single state and D.C. require permission to travel for either their probation or parole population — and almost all require permission for both.

It’s important to note that “standard conditions” are just part of the picture of probation and parole conditions, because courts can — and very frequently do — impose any number of additional “special conditions.” So even if travel restrictions are not included in the standard conditions applying to everyone on probation or parole, they may still be imposed at the discretion of the court or community supervision agency.

Limited abortion care options are made worse by these standard conditions

We next looked at each state’s abortion bans and restrictions alongside their standard conditions of probation and parole. This analysis gets to how quickly state laws foreclose the possibility of in-state abortion care for women under either form of community supervision, forcing them to request permission to seek care in another state instead. We find that the much tighter restrictions imposed by states since the Dobbs decision put over 400,000 more women in this precarious position than there were under the protections of Roe v. Wade. Alarmingly, we find that only 1 in 6 women on probation or parole can access abortion care at any stage of their pregnancy without needing permission to cross state lines.

Delving deeper, our analysis shows that, excluding federally supervised populations:

- Over half (53%) of women on probation and parole live in the 21 states that the Times identified as banning abortion care at an earlier point than the standard set by Roe v. Wade (i.e., the highly variable point of “fetal viability”). Less than 3% of these women are able to travel across state lines without permission.

- Nearly one-third (31%) of all women on probation and parole live in states that now have a total abortion ban. Of these, just 4% have no standard condition restricting travel.

- Another 17% of women on community supervision live in states that ban abortions at six weeks — a point at which more than 1 in 4 women are not yet aware of their pregnancy.

- Only 16% live in places without abortion bans and can access abortion care at any gestational point without crossing state lines.

Importantly, even when parole or probation authorities approve interstate travel, the process of getting a “travel permit” takes time and logistical coordination — and sometimes even fees. This necessarily delays abortion care, increasing the risk of complications and often further limiting access. For example, a woman on probation in South Carolina who only becomes aware of her pregnancy when she’s eight weeks along will have to travel out-of-state for an abortion. But if it takes two weeks for her to get permission to travel, a non-surgical abortion is likely no longer an option, as the necessary medications are only approved for use until 10 weeks’ gestation.

A travel restriction is just one of many barriers to healthcare for people on probation and parole

Interstate travel restrictions are just one of the barriers women — or for that matter, everyone on probation and parole — face when it comes to accessing health care. As we’ve already touched upon, some standard conditions restrict travel across much smaller areas, such as counties or court districts. Similarly, people on electronic monitoring — an increasingly common condition of community supervision that amounts to a form of “e-carceration” — are regularly blocked from leaving their home, workplace, or other approved locations. As we have explained before, people on electronic monitoring often report being denied permission to see a doctor or go to the pharmacy to have prescriptions filled.

Even in the few places that don’t impose restrictions on movement, financial costs often put healthcare out of reach for people on probation and parole. As we’ve found in previous research, people on community supervision tend to have lower incomes, with about 60% reporting annual incomes below $20,000. About 25% don’t have health insurance to cover the cost of even basic care — despite reporting worse overall health and greater levels of need. Probation and parole conditions often come with additional expenses as well, such as monthly fees and the costs of drug testing or electronic monitoring devices, which leave even less money for healthcare.

Finally, for women on probation and parole who need abortion care, there is a special risk of further criminalization, either for violating the conditions of their supervision or for the abortion itself. A recent law review article details the various laws used historically and currently to criminalize abortion seekers and providers, paying special attention to laws targeting people who choose “self-managed abortions” when they are unable to access care from the formal healthcare system. A report by researchers at If/When/How describes 61 cases, across 26 states, in which people were investigated or arrested for allegedly ending their own pregnancy or helping someone else end theirs. All were from 2000-2020 — in other words, pre-Dobbs. Efforts to criminalize abortion have only gained momentum since.

Conclusions

Ultimately, Dobbs not only made abortion care much less accessible for everyone who may become pregnant; it created new risks of criminalization as well. For people under supervision, those risks are intensified by the travel restrictions found in standard conditions across the country. As the Community Justice Exchange and Repro Legal Defense Fund explain in their organizing guide, “In states where clinical abortion is banned or inaccessible … [self-managed abortion] will likely be the abortion option most accessible to people under carceral surveillance, putting them at a risk for criminalization that people who can travel freely do not face.”

For this reason (among others), state legislators, courts, and community supervision agencies should minimize the number and restrictiveness of standard conditions imposed on everyone on probation and parole — and greatly reduce the use of these massive supervision programs in general. Courts should limit who they place on supervision, individualize supervision conditions, and apply those conditions only for as long as necessary to achieve results. This approach is far more likely to set people up for success than relying on restrictive, one-size-fits-all rules that only act as tripwires to further criminalization and punishment.

Certainly, whether it’s appropriate to restrict someone’s movement is among the most situation-dependent decisions supervision authorities can make, whether for work, family, religious, educational, or — as we’ve discussed here — health reasons. Restricting where people can go inevitably blocks many from accessing the resources they need, which in turn creates health and safety risks for both individuals and communities. These very real and life-threatening consequences must be taken into account and not discounted simply because of a criminal legal status.