“lowering out-of-pocket costs” number one health care concern

The International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans found employers are projecting a 7 percent hike for health care costs in 2024. Aon projected the average costs for U.S. employers paying for their employees’ health care could increase 8.5 percent to more than $15,000 per employee in 2024.

Voters remember the pain, not the gain

by Merrill Goozner

Here’s another problem for President Biden’s reelection team. In in policy arena that should be a strength for an incumbent who has lowered the uninsured rate to the lowest ever. When asked about health care issues voters are most concerned about, they choose rising health care costs, specifically, the rising sums they must pay out-of-pocket despite being insured.

The latest Kaiser Family Foundation poll of registered voters showed nearly half (48%) of the public rated “lowering out-of-pocket costs” their number one health care concern. That’s nearly triple the number who worried most about Medicare’s fiscal sustainability (18%) or getting more bang for their health care buck (18%).

As KFF president Drew Altman wrote in a column in February when the poll was released:

Between a quarter and a half of all Americans report real problems paying their medical bills depending on how sick they are. People are not economists, and they don’t think about out-of-pocket costs as a share of spending. People experience them as bills they often can’t afford to pay. The salience of out-of- pocket costs matters for elections, policy, experts, polling and how we in health policy frame the issue to garner public support.

Why Affordability Is the Big Tent | KFF

The key phrase in that quote is “depending on how sick they are.” It’s always important to keep in mind health care’s 20-80 rule: 20% of the population accounts for 80% of health care spending in any given year.

If you are well off and relatively healthy (thus in the 20%), then the occasional $20 co-pay for an office visit or $150 for an expensive test doesn’t make much of a dent in your monthly budget. But if you’re not well off and prone to the many ailments that strike working class people like hypertension, diabetes and workplace-related stresses and strains; or if your child has asthma, food allergies or ADHD; those bills can mount up quickly. When you’re in the lower half of the income distribution, even a few hundred dollars in co-pays can throw your monthly budget out of whack.

A research brief published today in JAMA Internal Medicine documents how rising out-of-pocket costs over the past decade-and-a-half hit less well-off people the hardest. A team of researchers led by Dr. Rishi K. Wadhera of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston reviewed out-of-pocket (OOP) spending for a representative sample (just under 100,000 families) of the 180 million people under 65 who have private insurance plans. The OOP spending included not just co-premiums, which are usually deducted from paychecks, but also co-pays and deductibles, which are only incurred when one visits the doctor, is hospitalized, picks up a prescription or uses some other medical service. It was also a period when a rising number of workers chose high-deductible plans from their employers’ options because they cost less in co-premiums.

They found mean spending paid out-of-pocket (half of families paid more; half less) rose 25.2% after adjusting for inflation between 2007 and 2019. Most of the increase came from co-premiums, not co-pays and deductibles (despite the rise of high-deductible plans in recent decades). That was twice the rate of underlying inflation in most of those years.

The health care tax on the poor

Lower income families suffered the most when the premiums deducted from paychecks rose faster than inflation. Their out-of-pocket expenses in 2019 ate up 26.4% of their “post-subsistence” income (not including food expenses) compared to 23.6% in 2007. For higher income families, out-of-pocket health spending took just 5.4% of income at the beginning of the study period and slight over 6% at the end, according to the study.

For both groups, health care’s biggest hit on household budgets took place during 2018 and 2019 — the first two full years of Donald Trump’s presidency. During 2017, his administration passed a massive tax cut for corporations and wealthier individuals, which raised that group’s discretionary income and thus lowered the impact higher health care expenses had on their family budgets. His administration also encouraged wider use of “junk” insurance plans, which by design have high-deductibles and limit coverage and are most often purchased by cash-strapped people without employer-based coverage.

Such plans leave policyholders, who were lured by the cheaper rates, with thousands of dollars in health care bills when they get sick. In March, the Biden administration issued stringent new rules limiting the use of junk insurance plans.

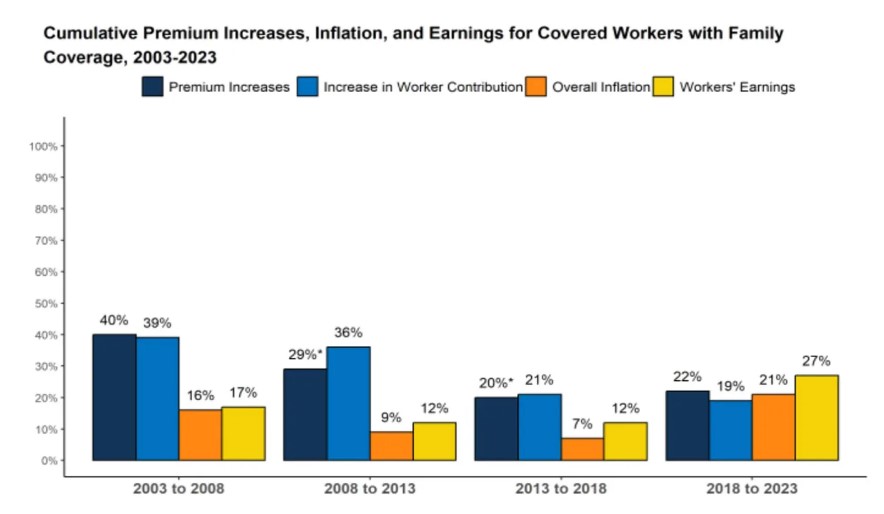

There has been some moderation in the bite premiums are taking out of workers’ paychecks in recent years. The Kaiser Family Foundation’s most recent annual employer benefits survey, released last October, showed cumulative increases in five year increments going back to 2003.

The most recent period, which included the Covid years when there was a massive infusion of government spending on health, saw a sharp falloff in discretionary health care spending. People during Covid avoided physician offices and hospitals whenever possible. The net result was the slowest rate in premium increases in over two decades, and the first-time premiums rose at slower rate than workers’ wages. (See chart below.)

Of course, after a few years of post-Covid full employment and rising wages, people are finally catching up on their non-emergency health care needs. So, households are once again feeling the pain of high out-of-pocket expenses.

And, unfortunately for the president, no one thinks about the fact their wages are rising faster than their premiums, co-pays and deductibles when they get hit with hundreds of dollars in bills. That number can soar into the thousands when they’re in high-deductible plans, which are now offered by 30% of employers

while health care costs is one of the biggest challenges to health care. and the junk insurance policies are a complete waste of money. another challenge is even if you have insurance, not you have a problem finding a qualified provider. in some locations (usually in ‘smaller cities’ to ‘medium citoes’ ) it seems that finding a provider than can help you is difficult at best, if not impossible. and with the consolidation of the health care industry, costs are going up!

@dw,

Not just consolidation, but the destruction of community hospitals by private equity. American capitalism is destroying American public health, aided and abetted by the GOP. What’s needed here is government regulation. When it comes to womens’ bodies, the GOP is all for government regulation. When it comes to the health of rural citizens, they’re opposed.

it’s that “tradition” thing.

you see, there were no vaccines in 1620.

life was so much better then.

yea we had all the food we needed, and werent hot or cold, we had all the water we needed, no one was left in want