Scenes from the employment report: an important trend in self-employment; and real aggregate payrolls

Scenes from the employment report: an important trend in self-employment; and real aggregate payrolls

– by New Deal democrat

We’re still in the week of drought following the payrolls release last Friday. Today let’s take a look at a few more items of interest from the Household Survey side.

As you probably recall, the bottom line employment numbers in the 2 reports diverged sharply in May, with the Establishment survey showing a 339,000 gain, but the Household survey showing a -310,000 decline.

I have to credit a commenter at Econbrowser for this, but it turns out what made the lion’s share of difference was self-employment. And it turns out that self-employment has been a significant player for over 2 years.

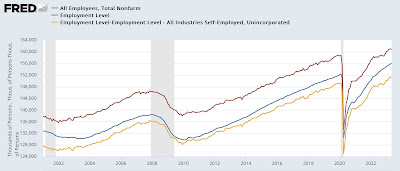

Here is what the number of reported self-employed looks like for the past 30 years:

While there’s no overwhelming driver as to the overall number, there’s no denying that there was a big surge in reported new self-employment in the year after the pandemic hit. This peaked at about 10.3 million in July 2021. As of last month, it had declined all the way back to its pre-pandemic baseline of the previous 10 years at 9.4 million.

It’s a noisy series, and a rebound in June would hardly be a surprise. But in general, the number of self-employed has declined on average about 40,000 each month for the past 2 years. It’s also worth noting that in the past 30 years, a declining trend in self-employment has been in place before each recession, which makes perfect sense, although the data is noisy enough over the longer term that I don’t want to go beyond that.

But also, since the self-employed are not counted in the payrolls survey (blue in the graphs below), once you subtract them from total employed in the Household survey (red), you get a number much closer to the payrolls number:

And when you look at that monthly since 2021, you see that self-employment has been a major contributor to the Household survey’s overperformance then, and its underperformance since March of 2022:

In particular, in the past year in all but 2 months, non-self-employed employment in the Household survey has been better than the headline number, and significantly closer to the payrolls number.

Which leads to an interesting proposition: that with a tight labor market, higher pay, and many companies continuing to allow work from home, about 40,000 self-employed each month have decided to become employees. Since both sides of the transaction are counted in the Household survey, but only the gain in employment at a firm is counted in the Establishment survey, this accounts for about 40,000 a month in payrolls’ relative outperformance.

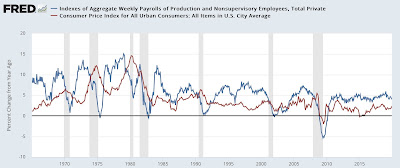

Next, let’s turn to one of the best “fundamental” indicators in the report: real aggregate payrolls. This tells us how much the working/middle classes in the US as a whole are taking home, in terms of buying power. As shown in the YoY graph below, it has had an excellent record in nowcasting expansions and recessions:

If YoY inflation is higher than YoY aggregate payroll growth, you’re in a recession. Otherwise, you’re in an expansion. Note that in the case of several slowdowns that were not recessions, notably 1966, 1984, and 1995, the two lines came close to crossing but did not do so.

Here’s what the same data looks like since the pandemic:

Since last September, the two lines have gotten no closer, and have even parted a bit, consistent with a slowdown that has not been a recession.

Here’s what that looks like on a monthly as opposed to YoY basis:

Although nominally aggregate payrolls growth has been erratic this year, it is holding up at better than +0.5% on average per month. Meanwhile inflation has been generally abating since last June. We can expect this trend in inflation to continue at least for the next several months until gas prices no longer compare with the spring 2022 spike.

Bottom line: real aggregate payrolls is perhaps the best single datapoint arguing that the 2022-23 slowdown has not turned into a recession, and that is likely to continue in the immediate future.

Scenes from the May employment report: leading indicators and the big picture – Angry Bear, New Deal democrat.

Scenes from the April employment report: the Fed just can’t kill the employment “beast,” Angry Bear, New Deal democrat.