The Impending Doom, Gloom, and Fiery Crash of Independent Meat Processors

Market consolidation is nowhere near revolutionary news these days, as we have seen meat processing plants loom ever larger. Sitting right outside of major or semi-major metropoles, freshly frozen stock of proteins are brought in at all hours of the day and night to sell at a meat retail counter in all large chain grocers around the country. This has more or less been the model since the 1980s where corporate consolidation, mergers, acquisitions, and vertical integration have all lead to the downfall of local butcher shops, and even decimating larger regional outfits. The large behemoths spanning multinational presence have consolidated tight control on everything but the product, and not for lack of trying.

Agricultural journalism is as much about the click bait as any other media outfit (the title of this post included), except that almost all of ag journalism is a for us by us operation. Agricultural journalism is funded by ag advocacy groups such as the beef council, checkoff, lenders, equipment manufacturers, seed and chemical companies, etc. The mainstream media tends to run stories exclusively about Bill Gates, China, or other political buzz to get picked up by the social media machine, news aggregators and clicks for advertising. And it comes as no surprise that status quo opinions and analysis become mainstream in the Ag sphere rather quickly. Tyson foods and the Beef Checkoff spend millions in ads. So why would anyone want to challenge the narrative?

Case in point, Alan Guebert has been picked up by almost every major agriculture journal, news and media outlet for his position that small beef packers opening up regionally will all fail as the market share enjoyed by the Big Four is unlikely to yield them any retail space at market.

Now, in principal, I don’t outright disagree with everything Mr. Guebert asserts; meat packing is a difficult business to get into and doubly more difficult to stay above water in. But have we reviewed any history prior to asserting the new fangled abbatoirs popping up seemingly out of nowhere are Doomed?

Let’s start with the facts. Alan takes an analysis of a few big money projects coming on line in the next year or so. Some projects are already up and running and doing well, some are on the way up and have different intended goals. So let’s examine.

A group in South Dakota is building a $1.1 billion beef and bison packing facility that will employ 2,500 people and process 8,000 head per day. That’s a substantial amount of throughput for a Midwest plant. Even more astounding is the $670 million coming from private cattle ranch and feedlot operations. The investment from those who grow the product and the venture capital coming together to offer partnerships seems to have stoked new fuel in the competitive fires of capitalism in the meat industry.

They are not even close to being alone. Sustainable Beef is planning a facility in North Platte, Nebraska. Cattleman’s Heritage Beef is also courting investors for a processing facility in Council Bluffs, Iowa.

In Texas, there is a large 3,000 head of cattle a day processing plant being built next year that is wholely owned by the Texas Cattlemen, endorsed by and also financially supported by Gov. Abbot. To frame perspective, 3,000 head of beef a day is 20% of the entire supply of Texas. This facility will be owned by the members in a cooperative fashion much like a lot of farm and ranch graineries, feed makers, dryers, gins, and suppliers. Cooperatives work by not taking excess profits. The members pay for the facilities and workers and the excess profits are distributed back to the member owners. This setup is a little different, but is being pushed by the famous XIT Ranch in the Texas Panhandle, and is rightfully named Producer Owned Beef.

There also are smaller regional outfits that are producer owned that are coming online for cattle owner use that will not sell direct to public. On the other side of the market, small regional butchers are also seeing their hayday with state inspection adherence for private label processing and packing for local smaller producers that sell to local restaurants, schools, or smaller grocers. Establishing a private label now requires a wait-list for state and federally inspected packers, some having to wait three to six months or even longer for a process date.

Where I disagree with Alan is that for his assertions to be true, we have to completely ignore the 20% of the total packer market who are not part of the Big Four, and the success they have enjoyed. History proves otherwise, Mr. Guebert, and here are a few examples.

Sam Kane Beef Processors has been around for a good while. Most people would not recognize the brand hauling from Corpus Christi, Texas, but some might recognize the private label brands being sold at major retailers today, such as legendary Half of Fame MLB pitcher Nolan Ryan’s private label beef that is carried exclusively at Kroger stores, or at his private label meat counter outside of Austin. Aside from scandals that have plagued Kane over the past few years due to mismanagement, the eventual buyer, STX Beef has also enjoyed a profitable business, at full capacity, processing 1,400 head of cattle a day, making it the 12th largest beef packer in the United States.

This is one example and there are many more scattered around the country that make up the 20% of not Big Four. Another example of a private label processor that supplies a large amount of beef to Houston, Austin, and Dallas would be Ruffino Meats, if one wanted to journey down the rabbit hole. But a bit of caution, some ‘independent” processors are LLC subsidiaries of larger packers such as Long Prairie out of Des Moines, Iowa which is actually owned by Premium Brands, a Canadian multinational.

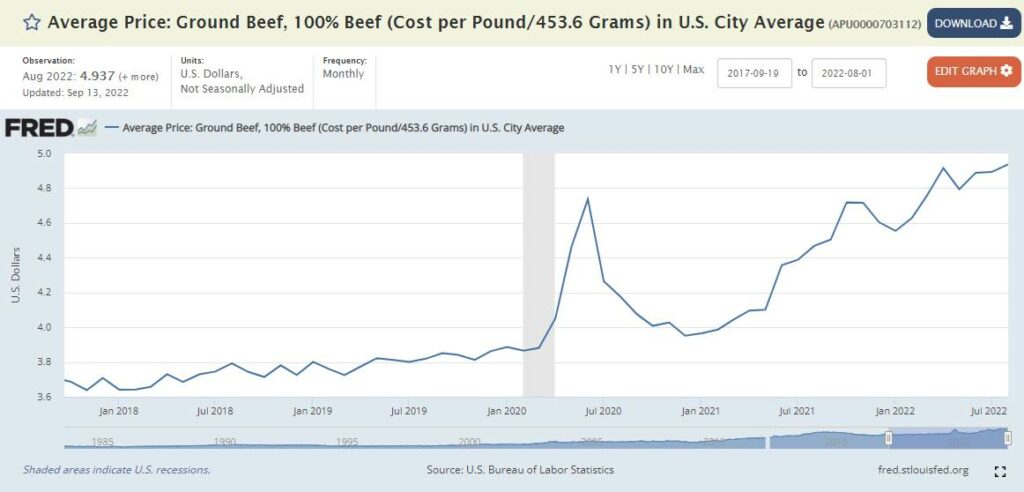

Further proof of independent processors going out on a financial limb is not hard to justify given the margins that the Big Four have operated under for the past two years. At first pandemic supply chain woes forced prices higher, followed by the resilience proven out in consumer demand slack. The short answer is the public is willing to spend more and the packers know it. Take for example the fed cattle spread over the past five years.

The Fed cattle prices have gone up significantly recently as feed prices have popped due to drought enduced silage shortages coupled with herd shrinkage. Yet, ground beef prices still remain at all times highs.

Rather than absorb the costs of production, packers have instead chosen to continue to hike prices in the name of inflation, steadying their margins on top of an already historically high cost environment for beef. Back in February of 2021, packer margins were way out of line with the market in general, and the packers have not reversed course.

Thus, if the ranchers can enjoy the same price levels for finished beef, what’s to stop them from feeding out the cattle on their ranches and then selling to an independent processor with retail contracts at local supermarkets? Cut out two of the middlemen seems to be a future path to stability for farmers, not the doom and gloom that media outlets would have us believe.

This sounds like a private sector version of the government encouraged dairy and fruit coops of the 1930s. I have friends who raise cattle and sometimes pigs for market. Raising animals for meat is hard enough, but their big challenges have been processing and distribution. Our area is now known for its beef, but for a long time one had to take one’s cattle to a distant slaughterhouse for lack of a local facility. Most of the farmers where I am are much smaller scale, but having a coop run slaughter and processing plant helps grow the smaller scale industry and gets the farmers more money.

Thanks for the write up.

Agricultural coops are still very much in place pretty much everywhere. Tillamook is a huge one out by you. Exceptional cheese.

Michael

They do make excellent cheese. On my way back and forth between Michigan and upstate NY, I would pass a cheese mfgr. Never stopped as an off ramp was not close to it and I was always in a hurry.