Cover All Births And Modernize Maternity Care

Medicare For All? Start At The Beginning: Cover All Births And Modernize Maternity Care | Health Affairs

It has been two years since I wrote on women’s healthcare and three important topics impacting women; clinical trials done without women participants, a failing birth control device – Essure, and maternal healthcare. The Health Affairs article is suggesting Medicare for all Maternal Care as an improvement to lacking healthcare for all women. Improving the availability of maternal healthcare for women is very much needed. As I wrote in A Woman’s Right to Safe Healthcare Outcomes; there is also a need for improving the care. There are too many symptoms being missed or ignored for the mother before, during, and after the birthing of a child.

Medicare is fee for service care. Medicare determines what will be paid. Those are the good parts. Dr. Donald Berwick claimed 30% of Medicare expenditures for care was waste and doctors knew it. However, Medicare for all Maternity is an important step forward which will level the field of care for “all” women.

_____________________

A Bit of History

EMTALA or the “Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act” passed Congress in 1986. Its purpose was to require hospitals to provide emergency care for everyone crossing hospital thresholds regardless of the ability to pay. It also provides a means to pay hospitals for those patients who could not afford to pay. With the passing of the PPACA, each person was to be insured in one form (Commercial Insurance) or another (Medicaid/Medicare). The Medicaid Expansion mandate for states fell by the wayside with the Roberts Court ruling. Going with it was the federal government reimbursing hospitals.

Within the EMTALA, Congress was establishing, delivering a baby was an exceptional occurrence with inherent risks, and in such cases, delivery needed to be covered. Unfortunately, universal coverage for pregnancy was never been achieved with the passage of this bill. Although not having insurance at the time of delivery is not common, more than one in five people lack insurance either in the month just before pregnancy, during pregnancy, or in the postpartum period. With that being said, there was no provision made before or after delivery other than Medicaid and Medicaid will only cover 2 months of postpartum care.

The EMTALA is part of the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 or COBRA. Mitch McConnell (elected to the Senate in 1984), passed the bill with a 96-0 vote when bipartisanship was in vogue. President Ronald Reagan signed the bill on April 7, 1986.

Joe Biden’s American Rescue Plan passed without Republican votes. Within the American Rescue plan are provisions providing states the option to extend postpartum Medicaid coverage from 60 to 365 days. The ARP had unanimous support in the House as a stand-alone bill. While in the Senate, the support was not so strong and this time McConnell voted against healthcare for pregnant women. Also and as you may or not know, Republicans are attempting to use the funding for the American Rescue Plan to fund the proposed Infrastructure Plan.

Why is this so important?

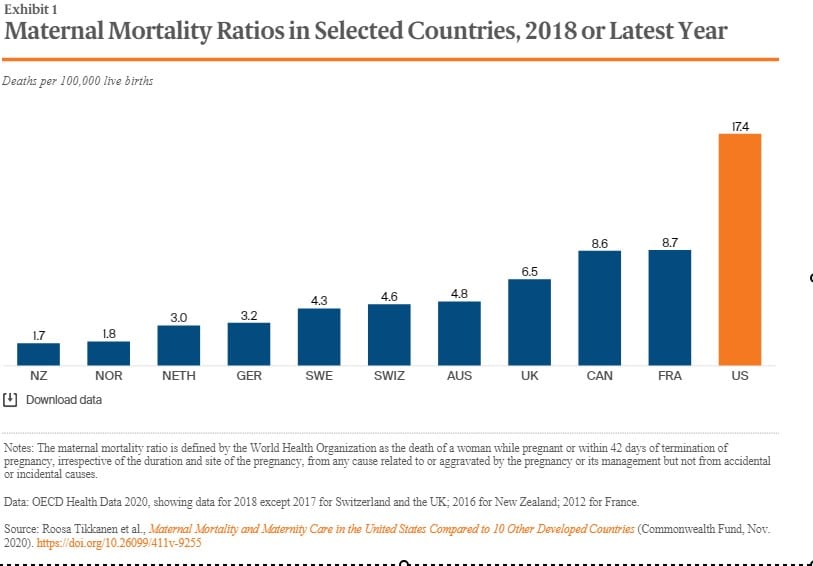

Women in the USA have a greater lifetime risk of dying of pregnancy-related complications before, during, and after birth than women in other countries.

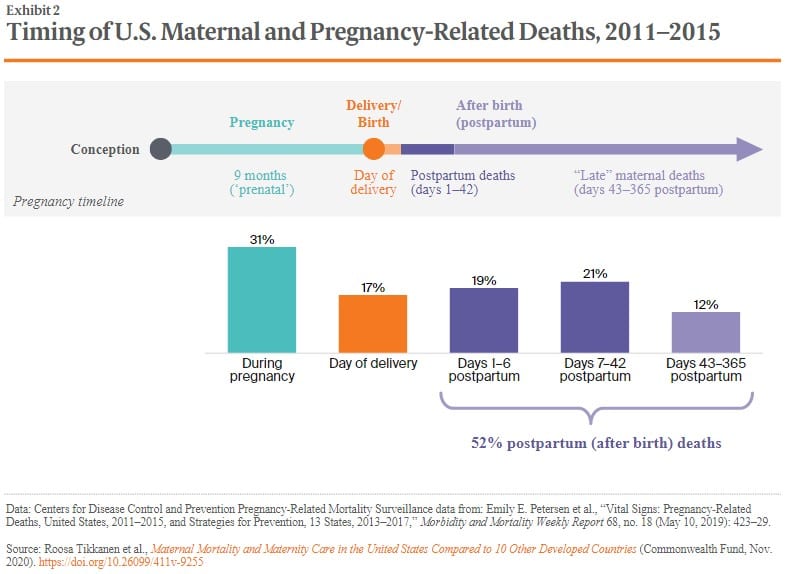

As the bar graph details, 52% of the deaths from pregnancy occurred after giving birth from day one to 364 days later. While (most) commercial healthcare insurance covers postpartum healthcare up to a year, Medicaid only covers two months of postpartum care. The most impacted by this lack of coverage are minorities who lack the resource for better coverage outside of Medicaid.

The emphasis of the bill is to fund Medicaid so as to provide the same care as what is provided by commercial healthcare and up to 1-year after the baby’s birth. Two months of Postpartum Medicaid is provided, The care during and after is supposedly less than what is normally provided. It is a good goal to emphasize. The expansion of Medicaid maternal coverage should include the quality of care before, during, and after delivery for those lacking access to healthcare and the means of getting it through healthcare insurance today. Included in the expansion of the length of coverage is an effort to improve the care

A little more than a year ago, I touched upon Maternal Healthcare, A Woman’s Right to Safe Healthcare Outcomes, and the dangers inherent in it. When I wrote on this one topic, I covered a story of a delivery that cost the life of the mother during a successful birthing of the child. All the warning signs were there of a mother in trouble and missed. Unfortunately, this is not an uncommon occurrence in the United States which still has the most expensive healthcare for a civilized nation.

Some data, a comparison to other countries, and a story.

In A Woman’s Right to Safe Healthcare Outcomes, I gave the death rate statistic for the US as being 26.4 deaths per 100,000 with the UK being at 9.2. As shown by a more recent chart, the US is now at 17.4 deaths per 100,000 with the UK at 6.5 . . . a similar ratio of ~3 to 1 between the two countries. Improvement was experienced and the US still lags far behind other less costly countries.

Emphasis is on successful deliveries of a baby and the care to mothers; but as the chart details, the death rate in the US far exceeds that of other countries. It is not that mothers are being ignored, it is a lack of attention to the warning signs of problems. Access to more healthcare, insurance coverage, and more money will not resolve the issues of better care for women before, during, and after the birth of a baby.

Even with an improvement, the US still has the highest maternal mortality rate in the developed world, racial disparities amongst citizens in maternity access and outcomes, and dangerous declines in the availability of maternity care in nearly all parts of the country. Childbirth and newborn care are the most common and costly hospital conditions for Medicaid and also commercial healthcare insurance. Yet, the United States spends more on maternity care than any other country on earth.

The EMTALA is an effort to extend care under Medicaid and providing better funding for it as well as overall maternal healthcare. However before, during, and after delivery; women are still in danger due to missing the signs of a woman in distress or are misdiagnosing the signs.

As taken from A Woman’s Right to Safe Healthcare Outcomes:

With 39 weeks of a good pregnancy, the expectant mother went to the hospital to induce labor. Inducing typically ends up with a cesarean delivery. Twenty-three hours later, the doctor delivered a normal, healthy baby girl. Reoccurring sharp pains in the kidney area were alleviated with more epidural. In 20 hours, a healthy mother before the birth of her daughter died after the birth.

The pain came back 90 minutes after the birth. Lauren’s doctor husband questioning the ob/gyn, was told the pains were acid reflux, which is a common reaction after birthing. The pain increased, her blood pressure spiked at 169/108, and her husband asked the OB whether this could be preeclampsia (which he suspected).

Admission blood pressure upon was 147/99. She was experiencing similar readings during labor. For one period of 8 hours no readings were made. All eyes were on the health of the baby, not on the mother, and what could be coming to pass. For a woman with normal blood pressure such as this young mother, a blood pressure reading of 140/90 could be indicative of preeclampsia.

Her husband reached out to another doctor, he anxiously relayed the symptoms, and she quickly diagnosed what the young mother was suffering from . . . a disorder called HELLP syndrome or Hemolysis, (a breakdown of red blood cells); Elevated Liver enzymes; and Low Platelet count. A disorder if not treated quickly leads to death. The doctor emphasized the need for a quick response to the symptoms told to her.

This is only a brief recital of the tragedy which befell Lauren Bloomstein and her husband Larry. With additional delays in finding a surgeon, Lauren began to experience bleeding in her brain which would lead to paralysis. She knew she was dying before her husband’s eyes. A neurosurgeon was called in to relieve the pressure and stop the bleeding. Since her platelets were low he could not operate, the hospital did not have an adequate supply of platelets, and by the time additional supply arrived it was too late. She was brain dead. A previously healthy Lauren passed on after her daughter was placed next to her one last time.

The warning signs of life-endangering problems were there and missed (pain in the kidney area) or ignored (abnormal high blood pressure for Lauren). Excuses for pain (reflux) were made. Pain killers administered to dull the pain and other symptoms (blood pressure) not explored. She was deteriorating in front of her husband who suspected preeclampsia.

The missing part of this was the protocol to diagnose early on and prevent Lauren from slipping into preeclampsia. This is not an isolated incidence as the deaths of women giving birth keep increasing as evidenced in the attached chart.

What makes this story important is the mother was a nurse, in good health, married to a surgeon, having her baby in a reputable hospital, tended by an obstetrician/gynecologist, was of white background, and insured. All the right elements were there for successful delivery and a healthy surviving mother after the birth. All the right elements were present for normal delivery.

Doctors missed the warning signs of a mother going into crisis and in stress.

“And my friends were like, ‘We can’t accept that . . . With our technology, every single time a woman dies [in childbirth], it’s a medical error.'”

The Other Story:

There are two stories, one for economically secure women and another for minority, native American, rural, and lower income women. The numbers worsen for women of color with their being more likely to die in pregnancy or childbirth.

- Women of color are nearly four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women.

- In high-risk pregnancies, African-American women are 5.6 times more likely to die than white women.

- Amongst women diagnosed with pregnancy-induced hypertension (eclampsia and pre-eclampsia), African-American and Latina women were 9.9 and 7.9 times in danger of dying than white women with the same complications.

- Native American and Alaskan Native women experience similar issues and lack of care.

Medicaid pays for half of all U.S. births and less than commercial insurance. Medicaid has high fee rejection rates and only provides postpartum care for two months. It leaves a substantial gap after child birth when other issues can arise.

Maternal mortality statistics hides a variation by race and ethnicity. White mothers being in the majority and experiencing 14.7 deaths per 100,000, while:

- Black non-Hispanic women experience deaths per 100,000 is twice that of white women at 37.1.

- Hispanic women experience a lower rate of 11.8 deaths per 100,000.

With Covid, the racial disparities in maternal care outcomes amongst Black and Hispanic women is inadequate. Medicaid is cheap and doctors and clinics can also reject it.

The Goal?

What the authors of this article attempt are to establish is a “rationale and broad outline of a national plan for Medicare for All Pregnancies (MFAP)” surpassing what is existing, It would eliminate uninsured pregnancy, birth, and the first postpartum year for both the mother and newborn. The goal is to establish parity between public and private health insurance coverage. It proposes high-value, equitable care through the fostering and implementation of evidence-based interventions and innovative care models.

The end result could be a true maternity care system improving outcomes for all families with cost savings to fund extending maternity and perinatal coverage to everyone. It is a noble goal.

If you do have private healthcare insurance, the care you receive will be mostly exceptional. The charge costs for commercial healthcare will be higher as Medicare and Medicaid set costs/prices. While accepted by many providers, Medicaid pays less than insurance, restricts care, and has time limits to receiving postpartum care. Medicaid provides two months for postpartum maternal care today while commercial healthcare insurance maternal healthcare can last a year.

MFAP (Medicare for All Pregnancies) eliminates the lack of insurance for pregnancy, birth, and the first postpartum year. It introduces payment parity between public and private health insurance coverage. MFAP transitions to high-value, equitable care by fostering the implementation of evidence-based interventions and innovative care models. MFAP could seek to remedy chronic “economic and care disparities in access to high-quality care during pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum year and potentially serve as a laboratory for the implementation of Medicare for All across the entire US population.

There is a need for such a program to provide extensive maternal healthcare for all women who lack it. Even with the PPACA implementation and expanded Medicaid, American women are still in danger. Comparing to their Canadian sisters, American women are twice as likely of dying from the start of pregnancy up till one year after the birth of a child (defined by the Centers for Disease Control). However, the issue is more than providing an avenue for care.

Improving the quality of care is important too as many women are dying of complications. Our maternal healthcare is missing the problems and the signs of stress before, during, and after a birth. These complications are picked up in countries having far less funding for healthcare. There was no reason for Lauren Bloomstein to die as the signs were all there. Neither is there a sound reason for the United States having Maternal Mortality ratios twice that of other countries.

ReportfromNineMMRCs.pdf (cdcfoundation.org)

The New U.S. Maternal Mortality Rate Fails to Capture Many Deaths — ProPublica

Maternal Mortality Maternity Care US Compared 10 Other Countries | Commonwealth Fund