How Redistribution Makes America Richer

By Steve Roth (originally published at Evonomics)t https://evonomics.com/how-redistribution-makes-america-richer/

You hear a lot about bottom-up and middle-out economics these days, as antidotes to a half-century of “trickle-down” theorizing and rhetoric. You’re even hearing it, prominently, from Joe Biden:

They’re compelling ideas: put more wealth and income in the hands of millions, or hundreds of millions, and you’ll see more economic activity, more prosperity, and more widespread prosperity. To its proponents, it seems deeply intuitive or even obvious, a formula for The American Dream.

But curiously, you don’t find much nuts and bolts economic theory supporting that view of how economies work. There’s been lots of research on the sources and causes of wealth and income concentration. There’s been a lot of important work on the social and political effects of inequality — separate (though tightly related) issues. But unlike the steady stream of “incentive” theory from Right economists over decades, Left and heterodox economists have largely failed to ask or answer a rather basic theoretical (and empirical) question: what are the purely economic effects of highly-concentrated wealth, held by fewer people, families, and dynasties, in larger and larger fortunes?

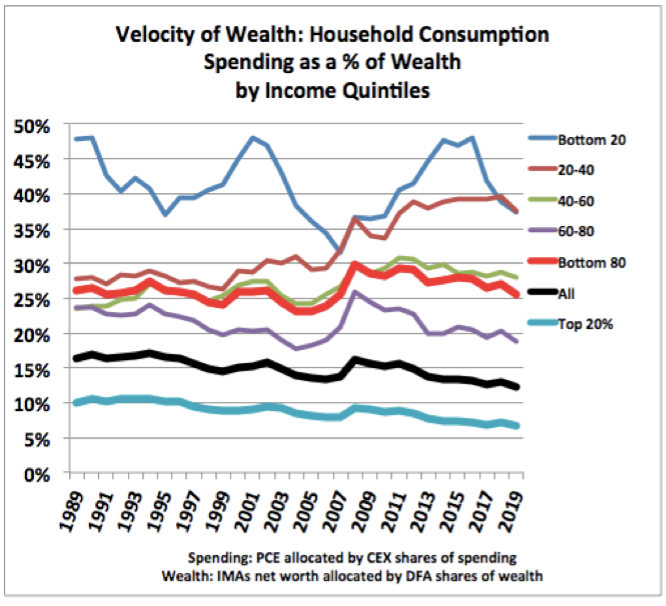

In a new paper and model published in Real-World Economics Review, I try to tackle that question. The model takes advantage of national accountants’ wealth measures that have only been available since 2006 or 2012 (with coverage back to 1960), and measures of wealth distribution that were only published in 2019. Combined with thirty+ years of consistent survey data on consumer spending at different income levels, the paper derives a novel economic measure: velocity of wealth.

The bottom 80% group turns over its wealth in annual spending three or four times as fast as the top 20%. The arithmetic takeaway: at a given level of wealth, more broadly distributed wealth means more spending: the very stuff of economic activity, which is itself the ultimate source of wealth accumulation.

The details of the model are somewhat more complex, but it only employs five easy to understand formulas — all basically just arithmetic, and all expressed without resort to abstruse symbols; they use plain language.

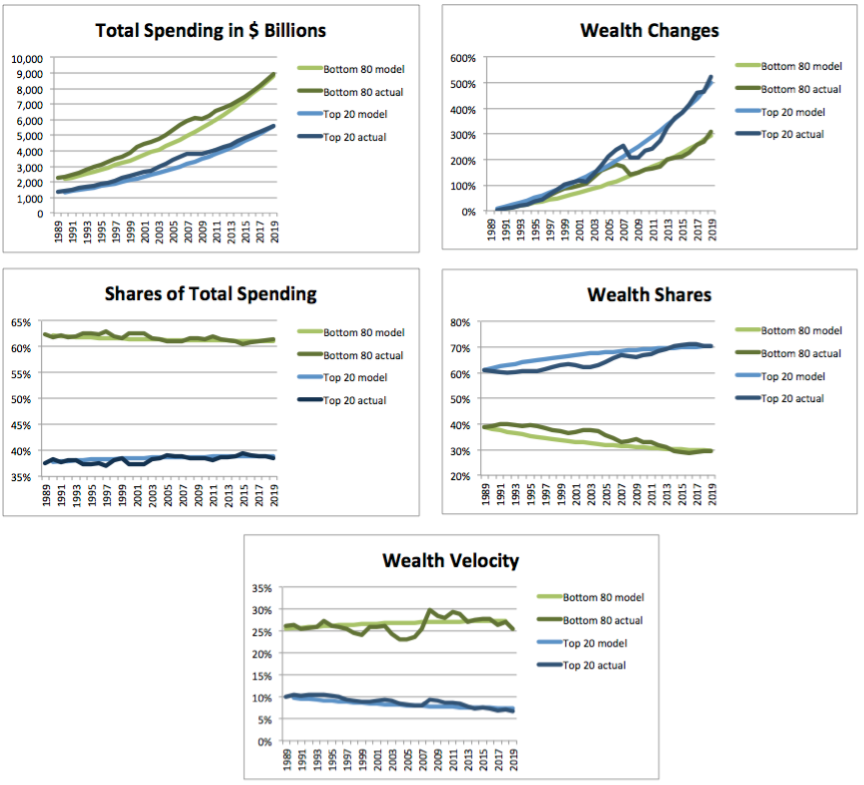

How good are the model’s predictions? It starts with just two numbers in 1989 — the wealth of the top 20% and the bottom 80% — and extrapolates forward using those few formulas to predict levels of wealth, spending, and shares of wealth and spending, thirty years later.

Compare the model’s predictions for 2019 to actual results; in each case they’re almost identical.

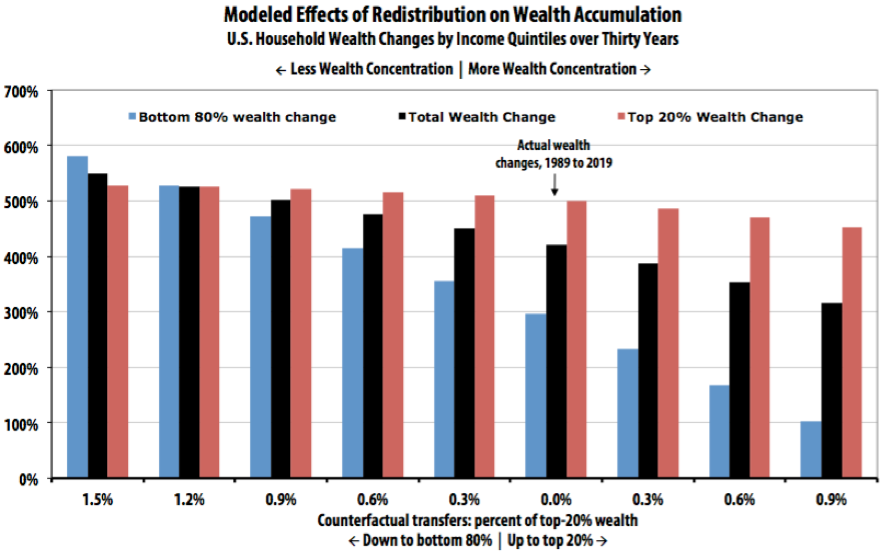

It’s easy to add counterfactuals to this model: what would have happened if some percentage of top-20% wealth was transferred, redistributed, to the bottom 80% every year over those three decades. The results are pretty eye-popping.

Downward redistribution appears to make everyone quite a lot wealthier, faster – especially (no surprise) the bottom 80%. Economic activity, annual spending, increases even faster. Taking the leftmost bars as an example: with an annual 1.5% downward transfer, greater spending would have resulted in a 549% total wealth increase, versus actual 421%. (To put that 1.5% downward transfer in context: the compounding annual growth rate on a passive wealthholder’s 60/40 stock/bond portfolio over that thirty years was about 7.5%. That’s all unearned income, received simply for holding wealth.)

Most of that extra wealth growth would have gone to the bottom 80% (wealth growth of 527% vs actual 295%), while top-20% wealth growth would also have been slightly higher than actual (526% vs 499%). The top-20% share of wealth would have remained unchanged, versus the actual share increase, from 61% to 71%.

With 1.5% in downward redistribution, 2019’s total consumption spending — a pretty good index or proxy for GDP — would have been 52% higher. Total wealth would have been 16% higher.

It’s worth noting: excepting the two leftmost scenarios (1.5% and 1.2%), the top 20% keep getting relatively richer than the bottom 80%. Avoiding the increased wealth concentration that we’ve seen since 1989 (or even reducing the 1989 concentration) would have required at least an annual 1.2–1.5% downward wealth transfer from the top 20%.

Get Evonomics in your inbox

The very richest percentile groups, of course, might not have gotten richer with downward redistribution. It would depend on the mechanics and progressivity of the transfers. The data available here don’t let us determine that using this model. But the transfers would have to be far larger than envisioned here before top-percentile wealth levels (vs their relative share) actually stagnated or declined. Absent quite extreme redistribution, the rich keep getting richer as the economy grows. But with adequate redistribution to counter the ever-present trend toward economy-crippling wealth concentration, everybody else prospers as well.

The paper, model, data, and all calculations are available here.

mmm… Interesting but what I would really like to know about are the regional effects. I think some areas are constantly drained of wealth and that it accumulates in other areas. An area being drained of wealth is like an everlasting depression. (But I don’t think wealth is easy to measure so for empirical studies I think is a bit difficult to use. For instance as Chris Dillow argues your house is not net wealth e.g. https://stumblingandmumbling.typepad.com/stumbling_and_mumbling/2014/05/housing-vs-financial-wealth.html ). Redistribution between people can also be redistribution between areas.

>Chris Dillow argues your house is not net wealth

1. I never know WITH “net wealth” means. Is it different from net worth? Net of what? What’s “gross wealth”?

2. Robert Barro claimed that holders’ Treasury bonds are not “net wealth,” cuz somebody someday might have to pay taxes. Hmmm.

3. If you’re saving for retirement, eventual downsizing and long-term care, and watching your home skyrocket in value — increasing your net worth — you can spend more out of current income now (vs saving) without worrying that you’ll eventually be facing cockroaches and cat food.

Yes, this is Steve Roth of all people bruiting the “lifetime income hypothesis.” But as a moderate wealthholder, age 63, who has an explicit goal of handing my last dollar to the doctor on my deathbed (or even better: the bartender!), it makes a lot of sense to me.

Three “natural” (free market) ways to achieve the same objective:

* * * * * *

*

*

*

Same three ways can save the republic from Republican Fascist Party (RFP) stealing the 2022 elections with gerrymandering and voter suppression. Because the same three issues can totally crack the Republican hold on non college voters. NYTimes Nate Cohn (their top numbers guy to me) that if you could have severed off Milwaukee, Detroit and Cleveland and cast them adrift in the Great Lakes and Obama still would have beaten all American war hero John McCain and Wall Street idol Mitt Romney. It wasn’t weakening Black vote the defeated Hillary, it was lost non college white vote.

*

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/23/upshot/how-the-obama-coalition-crumbled-leaving-an-opening-for-trump.html

*

Don’t forget that 74 million voted for the RFP candidate — and that a mere 45,000 votes in three states could have reversed the outcome (maybe if the RFP hadn’t had the virus to trip themselves up on.

This new comment setup is getting impossible to use. How do you put a link in without a piece of it being plastered below. The NYTimes link only works if you first right click and then hit your choice of “open with” (new private window for one choice). Nice (unexpected) map though — maybe one picture is worth a thousand words.

Bottom up economics is just basic accounting. You don’t need anything fancy. Even better, empirically, we’ve seen that works. I’m glad to hear some economists are trying this approach. One of my big complaints for years has been that a lot of economics theory makes no sense from an accounting point of view.

“makes no sense from an accounting point of view.”

Explain some more?

@Steve Roth,

[Any chance that you are related to Big Daddy Ed Roth? That remote possibility is what inspired me to answer as well as some opportunity for fun.]

>Chris Dillow argues your house is not net wealth1. I never know WITH “net wealth” means. Is it different from net worth? Net of what? What’s “gross wealth”?

[A house is asset wealth, but with a mortgage then part of that wealth is gross. Net wealth would be equity for that asset, but overall for the person then net wealth is the FMV of all assets minus all financial liabilities. A house is a special case, but then Chris Dillow is also a special case. Most people feel that they need somewhere to live, but need Chris Dillow not so much. Owning a home comes with hidden liabilities affectionately known as maintenance.]

2. Robert Barro claimed that holders’ Treasury bonds are not “net wealth,” cuz somebody someday might have to pay taxes. Hmmm.

[Who is Robert Barro? OK, that was a joke. Robert Barro is a bad joke along with his twin idiot brother Bob Lucas. It is not like they do not know anything because any idiot knows at least a few things, but they are the wrong guys from which to take advice, at least on macroeconomics.]

3. If you’re saving for retirement, eventual downsizing and long-term care, and watching your home skyrocket in value — increasing your net worth — you can spend more out of current income now (vs saving) without worrying that you’ll eventually be facing cockroaches and cat food.

[Retirement is good, did that June 2015. Have no plans for downsizing or long-term care, but do have clear title on home and insurance to cover if no way to avoid those awful things for so long as I need to provide for my wife. For me alone, then there are better exit plans such as speedball. In any case fixed income and insurance beat the shit out of just trying to save for an indeterminate number of years.]

Yes, this is Steve Roth of all people bruiting the “lifetime income hypothesis.” But as a moderate wealth-holder, age 63, who has an explicit goal of handing my last dollar to the doctor on my deathbed (or even better: the bartender!), it makes a lot of sense to me.

[I can admire the sentiment without validating the logic or lack thereof. In any case, good luck with that.]

Roth the drag strip racer? US 30?

I need a definition of “America” because people keep saying that “America” is so far in debt that it can not possibly ever recover.

@Run,

Just asking, but not likely. Big Daddy Ed Roth was Ratfink crazy, but nobody’s fool.

Ron:

Morning from Phoenix today. A week ago it was Denver. I thought you were referring to such a person. Monsters of the drag strip. I pulled your comment out of the trash and doctored it (too many space after sentences which I think got you there in the first place).

Steve may answer. He is a pretty good guy.

Run,

I guess there are Bobs worse than Barro and Lucas. Mundell comes to mind.

Real Keynesians are not overly fond of neoclassical economists of any variant.

Ed Roth was on a Pickers episode, first time I got excited about watching one of my wife’s favorite shows.

Run,

EMike used to live in Phoenix. I have a good friend that lives in Tucson. Both tell me that Phoenix sucks politically, but they have nice yards there.

Ron

Do you believe they are even a matched with me?

No known connection to big daddy.

well, i can’t say i followed any of the economics, but i never do. neither does the country.

but owning a home is nice. unless you are owning it so you can sell it when you get old.

and you may have to, because even though the mortgage stopped, the taxes don’t. and i kind of like fixing up my home to suit my needs and tastes and not some hypothetical buyer. and moving to a smaller home means moving to a worse neighborhood. and what about the barn and horses and grandkids?

if i sold my home i could not buy another one with the money i’d get for it in any neighborhood i’d want to live in. rich folks have bought up all the land.

EWM

assuming you don’t already know this. the “America is so far in debt..” people are all damn liars.