A response to Kevin Drum: for wages and inflation, it’s all about the price of gas

A response to Kevin Drum: for wages and inflation, it’s all about the price of gas

Last week Kevin Drum had the following inquiry:

[H]ow is it that wages can go up but overall inflation remains so subdued? That seems to be the real disconnect here. During the dotcom boom, wages went up but inflation remained around 3 percent. During the housing bubble, wages didn’t go up and inflation remained around 3-4 percent. Right now, wages are going up but inflation has remained around 2 percent. Wages no longer seem to have much correlation with overall inflation.

I haven’t seen anyone address this specific issue, but I’d be interested in hearing more about it…. What’s the deal?

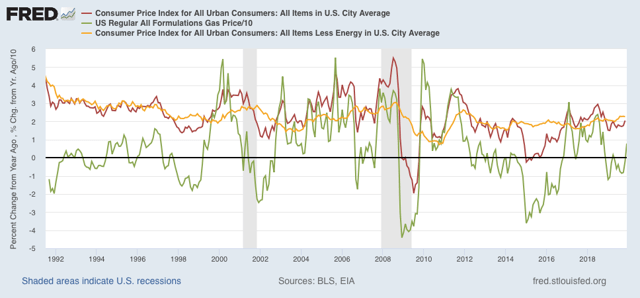

The answer here, I believe, is quite simply that in the modern era since 1983, consumer inflation more than anything else is about the price of gas. Let me show you why.

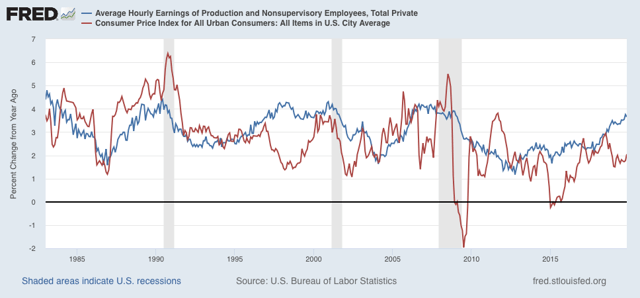

First, here’s the relationship that is the subject of Drum’s query: wages for non-supervisory workers (blue) vs. consumer inflation (red) YoY:

Overall inflation has been more variable than Drum’s summary indicates, but it is fair to say that during the 90’s and 00’s it averaged roughly between 1.5%-4% regardless of wage growth. During the present expansion,

inflation has been more variable to the downside, coming in negative in 2015. So, has inflation been non-responsive to wage growth?

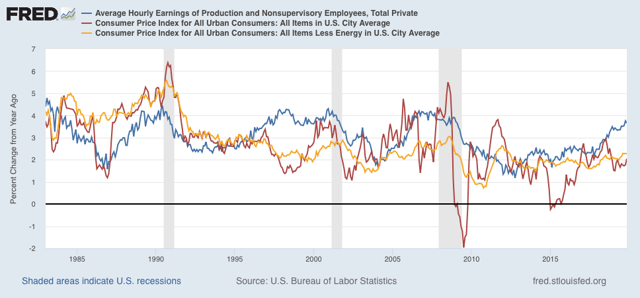

Not really, I think. To show you, let me first add in a third line, consumer inflation ex-energy (gold):

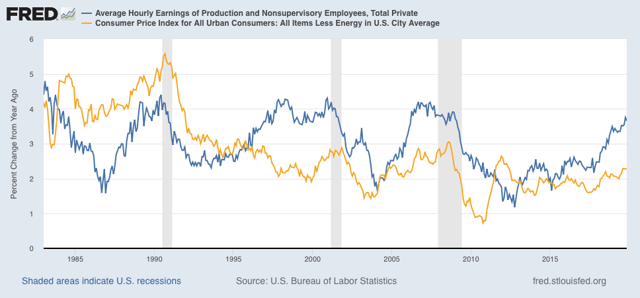

Note that it has been much more stable than overall inflation. But to cut down on the noise, and better show the relationship, let me take out overall inflation and just compare wages and inflation ex-energy:

Note three important things:

- Wage growth YoY does increase as the expansion goes on. In the past I’ve shown that this generally happens once the broad U6 underemployment rate goes under roughly 9%. So, a tighter job market even in the modern era does lead to faster wage growth.

- Inflation ex-energy has increased by roughly 1% YoY before each of the last 3 recessions, from 4% to 5% in 1990, and from 2% to 3% in 2000 and 2007 (which was presumably a motivating factor in the Fed’s raising rates during those times). It has also increased in the last couple of years to about 2.3%.

- In 3 of the 4 expansions since 1983, the increase in inflation ex-energy has broadly correlated with increased wage growth.

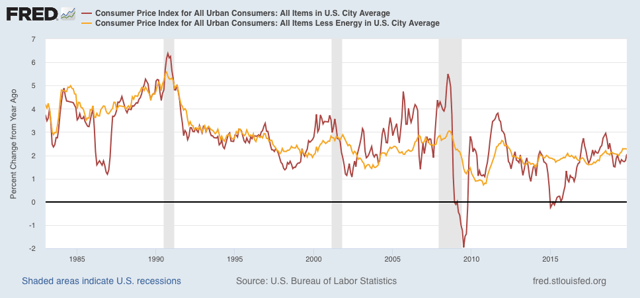

Next, let’s take out wage growth and just focus on overall inflation (red) and inflation ex-energy (gold):

While it isn’t a perfect relationship, what we learned going back to the 1970s is that oil prices feed through into overall inflation with about a 12 month lag. But on the other hand, the direction of overall inflation tends to feed back into energy prices with about a 24 to 36 month lag (this is something Mark Thoma wrote about maybe 8 years ago; I don’t have the energy to go back and dig up the link).

Put another way, core and overall inflation has something like a Sun-Jupiter relationship. Jupiter revolves around the sun, but the center of gravity is outside the sun, I.e., the sun’s direction wobbles in response to Jupiter’s gravitational tug as well.

To drive the point home, let’s add in the price of gas only measured YoY (divided by 10 for scale) (green):

Take a look at the late 1990s. The spike in gas (green) with a slight lag shows up in overall inflation (red), and then with a further lag in inflation ex-energy (gold). This again happens in 2011. Other times, overall inflation picks up exactly when gas prices go up – but the lag time for it to show up in inflation ex-energy remains.

In other words, there has continued to be a broad correlation between non-energy core inflation and wage growth. But the main driver of inflation for the past 35 years has been the price of gas, which has drowned out the trend in wages vs. inflation. To answer Drum’s question, that’s how “wages can go up but overall inflation remains so subdued.”

A multitude of economic sins were hidden by somnolent gas prices in 2019. The implication for 2020 is that, with an already tight labor market, if gas prices continue to rise YoY as they have in the past few months, with core inflation ex-energy already at 2.3%, the Fed might feel compelled to raise interest rates even if the economy seems to be faltering.

Hopefully, motor fuel prices in the USA will go to $5/gal before July 2020.

there’s a discrepancy between what NDD allegedly shows and what his headline says…the headline says “price of gas” ie, gasoline, while his charts show CPI less energy….CPI ‘energy’ includes utility natural gas service, electricity, fuel oil, heat oil, propane, kerosene, and other minor fuels in addition to gasoline…

nonetheless, gasoline is the biggest contributor to that metric and the correlation he draws out is interesting, even though i’d tend to remain skeptical that there’s the direct cause & effect relationship his headline implies..