Climate Change and Environmental Frames: The Consensus-Action Disconnect

(Dan here…I am always looking for new writers that might make a good fit for AB. Cactusman is in the field of behavioral economics in the private sector. I know that the topic of climate change is a hot one here, but remember this is his first here…)

by Cactusman

Climate Change and Environmental Frames: The Consensus-Action Disconnect

American attitudes toward the environment generally – and climate change specifically – could long be described as ambivalent. The Trump Administration seized on this ambivalence and spent the past year furiously censoring climate change scientists and scrubbing the EPA website of any references to dangerous words such as “greenhouse gases” and “science.”

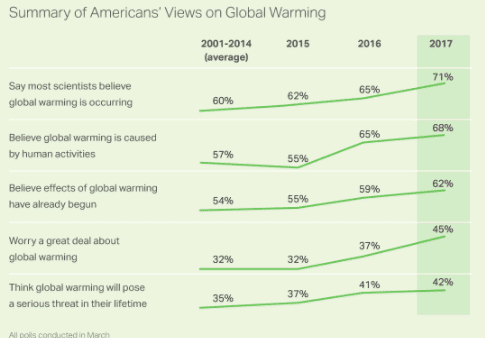

While survey research shows more and more Americans recognize climate change is caused by human activities and believe the effects have already begun, only 45% say they worry “a great deal” about it. Despite such shifts in public attitude, it’s hard to make a case that Americans are actually growing more concerned; when President Trump announced on June 1, 2017, that the US would withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement, his approval numbers in the following weeks didn’t take a hit.

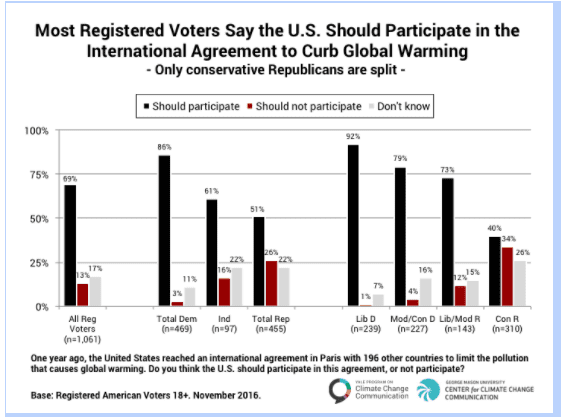

Some might chalk this resilience up to a diehard core of Trump supporters, who were pleased with the announcement, propping up his approval ratings. But research from Yale’s Program on Climate Change Communication shows that almost 70% of registered voters want the US to stay in the agreement (including majorities of Democrats, Republicans and Independents), while only 13% don’t.

While American views of climate change are continuing to shift toward concern, and an overwhelming majority of the country wants to stay in the Paris Climate Agreement, President Trump has not faced political consequences for his blatant attacks on science and the environment.

So how can the semblance of consensus be translated into action?

New research suggests that framing of environmental issues might be part of the answer. A recent paper published in the Land Use Policy journal, for example, tested two framing mechanisms to determine their effects on participants’ willingness to accept an incentive-based planning policy designed to prevent urban sprawl: goal framing, which uses language focused on either increasing the personal benefits or reducing negative externalities involved; and attribute framing, which highlights positive or negative aspects of a policy (in this case a subsidy or fee).

Participants were randomly split into four different groups and received messaging using either goal or attribute framing, which included a positive or negative emphasis embedded in the message. The test was carried out in Switzerland, so their direct democracy process could be used to accurately gauge “acceptance” of the frames. This allowed the researchers to determine whether people actually voted favorably for the policy rather than just indicating they would on a survey.

The results show that frames do matter, which isn’t a surprise. But more importantly, they demonstrate the effect different frames had on different stakeholders’ votes, in this case landowners versus non-landowners. In other words, it’s not just the frames that matter, but how and to whom they are applied.

In another recent study, risk framing, which draws on the human predilection to prioritize mitigating risk over the opportunity of benefits, was used to assess the impact on high school students’ perceptions and willingness to act to mitigate climate change. Students were presented with an article that followed a similar format but differed by framing the risks of climate change in four different areas: agriculture, health, community or environment. The results showed the agriculture and environment frames were most likely to motivate students to act to mitigate climate change.

These two studies – which are representative of a growing body of research – show that using behavioral framing methods, and, crucially, tailoring those methods to the specific audiences, are essential to driving action on environmental issues.

As evidence of climate change continues to mount, surveys are likely to continue showing Americans’ views of climate change trending toward consensus. But political will to reward action – or punish inaction – has, so far, not materialized.

While environmental framing isn’t a new concept, the rise of social media and digital channels offer far more scope for its use and refinement. The power of framing effects demonstrates that environmental advocates would do well to go beyond save-the-planet-style mantras and focus on testing and tailoring framing methods to deliver the right message to the right audience.

Messaging has been an action issue for many years now, with framing studies the most recent. Framing and/or communicating the issues is not the real problem. The problem is exaggeration of the potential consequences.

Most of us, skeptics and believers, can look back at the short term projections and realize they have not appeared. Long term projections are reliant on computer models that have been questioned for years, with even the modelers admitting a number of their weaknesses.

The underlying issue is the science around the impact of CO2 and the climate’s sensitivity (ECS) to it.. Estimates over time have been repeatedly reduced, with the current science showing another significant reduction since the last IPCC Report. ECS is one of the core if not the core of many of the models.

Without consistent and measurable projections the Climate Science projections are questioned. These questions are a natural step to making decisions re: investing in The Paris Agreement.

We have an administration that reflects more of the skeptical climate view point, and its members are re-reaming the climate issues accordingly. And that re-framing is one of the major concerns and why these types of articles are now popular.

The author concludes with this statement: ” The power of framing effects demonstrates that environmental advocates would do well to go beyond SAVE THE PLANET STYLE MANTRAS (an example of the exaggeration) and focus on testing and tailoring framing methods to deliver the right message to the right audience.” But, the re-framing performed by the skeptics currently in charge are moving the the targets and delivering a different message to the general audience.

Jeff, very nice. You can tell simply by the expected response above.

Meanwhile, I think all of these polls and lack of action not making sense can best be explained by one inescapable truth; not a whole lot of voters out there vote on issues, and those that do vote on issues do not vote because of the climate change issue.

Time for people to wake up in this country. GOP voters vote mainly because they are racists and have been convinced over the last fifty years that the federal government gives people of color money out of white people’s pockets, and that they are coming for the white women.

“Build That Wall” had nothing to do with infrastructure spending.

Jeff:

I work with Dan and moderate things so nothing gets out of hand. CoRev is one of our resident deniers of anything happening to the global environment as being caused by humans; hence, we should do nothing. Welcome to AB.

Jeff & Run, I don not belief this: “CoRev is one of our resident deniers of anything happening to the global environment as being caused by humans;…”

i have a long history here at AB, and my beliefs have been clear for years. Climate Change/Global Warming is clearly happening. Man has SOME responsibility for that warming, mostly because of land use. CO2 is a Green House gas SLOWING IR from the surface to space as does the more plentiful and widers Ir spectrum H2O gas. If you know the physics, you know that the IR photon is slowed for a period of nano to micro-seconds. It is NOT TRAPPED. Water and other surface molecules have that capability.

Most ill informed get upset when I and others try to dispel some misunderstandings of climate change and make the assumptions that we do not believe “anything happening to the global environment” and take our comments as attacks.

Skeptics are generally more nuanced in their views because we have studied the subject, and review both sides of the science.

You’re a liar.

You just write proven falsehoods and keep writing them and any attempt to correct you is responded to by total bs and make believe.

I would hope you would disappear until the next “pause”.

Hey CoRev,

You’ve apparently written on AB that you have a doctorate degree, but can you tell AB’s readers what discipline your PhD is in and the institution that provided it?

It might also be informative to know whether your work re Climate Change has ever been submitted for publication by a reputable peer reviewed scientific journal on Climate Change in he US. If submitted but never accepted it would probably more informative to readers. If you have been published in the reference journal(s) will you provide the links?

CoRev,

Hae any of your publications, if you’ve ever even been published in a reputable Journal relative to Climate Change, ever been referenced by the IPCC’s technical publications? and if so in which IPCC publication?

(or is the IPCC in your opinion just an irrelevant conspiracy?)

Hi All,

Love the fire in the discussion here and glad to have gotten my first post on AB. I can tell it’s a lively community, and have read it for a long time and am excited to contribute.

For me, part of the fascination in topics such as this one is just the “why” of it: why do people say they care about something when they don’t really care that much? Is it just a survey method failure? Are they lying? Delusional?

The reality is some mix of those (and other) factors and varies from person to person, which is why I like working in behavioral economics: it helps account for the variable irrationality in each of us. More to come as long as AB is happy to post them. Thanks!

Jeff

Soul:

Welcome to Angry Bear. First comments go to moderation to weed out spammers and advertising.

Jeff:

After reading through the comments another time, I finally made the connection to you and the article. I write on healthcare, student loans, manufacturing (my livelihood), and opioids as of late. Coberly and Bruce Webb are experts on SS. Barkley, PGL, Peter, Spencer, Ken, Robert are the resident economists. Sandwichman writes on Lump of Labor. Linda is a tax attorney. NDD writes on the economy. Dan covers many things and appears to have an expertise in psychology.

Bill

“The Consensus-Action Disconnect”

When in doubt, look at what people DO.

EM,

Of course CoRev lies &/or omits the most relevant aspects whatever aspect of Climate Change he’s pontificating about.

Crrrent case in point:

” If you know the physics, you know that the IR photon is slowed for a period of nano to micro-seconds. It is NOT TRAPPED. Water and other surface molecules have that capability.”

Eiher CoReve doesn’t believe the phyiscs of transmission and absorption of various electro-magnetic wavelengths by various molecules, or he omits that most of the IR is absorbed and not transmitted through the atmosphere…. with the largest cmpoeents of absorption due to CO2 concentrations in he upper atmosphere.

Per NASA

“The atmosphere is nearly opaque to EM [electro-magnetic] radiation in part of the mid-IR and all of the far-IR regions.”

It is the IR radiation that the is emittied FROM the Earth after being warmed by incoming UV & Visible light that is not able to be transmitted back through the Green House Gasses… it has nothing to do with nano-seconds delays at all. The greater the atmospheric concentration of green-house gases in the atmosphere, the less heat can escape. Most scientists understand this well. CoRev wants the public to think his own “science” is far superior to most scientists on the entire globe.

Some people always live in their own fantasy world or make one up to hope they can get others to believe in them. That’s a given of humanity since humans began. They lie, though not in their own fantasy world or the one they conjure up.. Those who live in the real world and have a decent understanding of it put the fantasy versions into sci-fi or story telling, or lying.

FWIW,

A little wonkish:

A gross, non-scientific, estimate of the relationship between atmospheric CO2 concentration and fossil fuels (NG, Coal, Oil) can be given by the change in CO2 and Fossil Fuel energy production on a globally averaged basis from 1970 to YE 2017. This estimate doesn’t include weighing each fossil fuel by it’s CO2 production per unit energy produced, so actually understates the relation of CO2 produced on a global basis to Fossil Fuel energy consumed.

Fossil Fuel Energy Consumption changes over time are averaged over the three fossil fuels consumed for energy (coal, oil, NG).

Data Source:

https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/global.html#global

+ Global Population

For the period 1970 to YE 2017 the CO2/Fossil Fuel Energy Consumed is has increased by 118% or 2.5%/year.

On a per Capita basis over the same period, atmospheric CO2 produced / Fossil Fuel Energy Consumption has increased by 7%/capita, or 0.15%year.

This assumes only that consuming fossil fuels for energy produces CO2 as a waste by-product. Some of this CO2 produced is absorbed by Oceans and Plants, however the Atmospheric concentration is net of these CO2 absorbers and because I didn’t weight each fossil fuel by it’s CO2/tonne of energy produced, then the relationship stands without considering Oceans and Plants CO2 absorbtioin.

The only part of this relationship that can refute it is to say that there is some other source(s) of CO2 production besides fossil fuel energy consumption and population growth that accounts for most of the increase in CO2 concentration in the atmosphere.

The conclusion is that atmospheric CO2 concentration increases over the period have been produced by human population growth (104%) as they consume more fossil fuel energy / person on a global basis.

Hence Human Caused atmospheric CO2 production via fossil fuel energy consumption. This is also the conclusion reached by most scientists and the IPCC

Now one can assert that atmospheric CO2 growth has little or very little or nothing at all to do with global warming or that it is totally or mostly counter-acted by something unrelated to Fossil fuel energy consumption.

But to make that assertion have any merit at all requires that atmospheric CO2 doesn’t absorb most of the IR energy emitted by he Earth…. e.g. refuting the physics of electromagnetic wavelength sensitivity to absorption and transmittance through other molecules, a fact that was scientifically well established already by 1890.

BTW, I won’t argue my above wonkish estimates or cause & effect with CoRev or anybody else. I’ll let them argue with the IPCC and majority of scientists that have studied and the relationships .

woops, on my wonkish estimate I forgot to include this data source (see Figure 6)

Longtooth,

I don’t get why you’re so sure of this.

1) the Earth is several billion years old and has undergone climate shifts from Ice Ages when glaciers extended to Arizona, and warm periods when dinosaurs lived in Antarctica, all without man whatsoever, why now is CO2 the driving force in global temperatures?

2) The concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere has increased from 275 PPM to 350PPM since industrialization. Or about 75 parts PER MILLION. So there are an extra 75 CO2 molecules floating around per MILLION atmospheric molecules. This truly a minute change. Does it outweigh, say, solar cycles

3) CO2 is at historic low concentrations, and there is no historical correlation between CO2 and global temperatures:

https://www.bing.com/images/search?view=detailV2&ccid=Epbn8cQm&id=6FBF60A3DF100B49922D5500E9C4B243AE05E10F&thid=OIP.Epbn8cQmuLKAg2UsXfUKhgHaEr&mediaurl=http%3a%2f%2fpapundits.files.wordpress.com%2f2012%2f10%2fhistorical-co2-levels.jpg&exph=417&expw=660&q=CO2+Levels+throughout+History&simid=608008938516385334&selectedIndex=2&ajaxhist=0

“Some people always live in their own fantasy world or make one up to hope they can get others to believe in them.”

I guess these scientists are living “in their own fantasy world”:

http://www.intellectualtakeout.org/article/5-scientists-skeptical-climate-change

LT, never said I have a PHD nor have I claimed to have written a paper for a scientific journal. I have said that I’ve studied this subject for years.

As i have said a little knowledge can be deceiving. I used my terms carefully. ” CO2 is a Green House gas SLOWING IR from the surface to space as does the more plentiful and wider Ir spectrum H2O gas. If you know the physics, you know that the IR photon is slowed for a period of nano to micro-seconds. It is NOT TRAPPED. ”

In the late 90s and early 00s trapped was a frequently used term, but things were not making sense. For instance, here are EPA documents which seem contradictory re: CO2 “trapping” .

“Gases that trap heat in the atmosphere are called greenhouse gases.” https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/overview-greenhouse-gases

and

“Greenhouse gases (GHGs) warm the Earth by absorbing energy and SLOWING the rate at which the energy escapes to space; they act like a blanket insulating the Earth….” https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/understanding-global-warming-potentials

Those two common statements/explanations of the Green House Effect left me wondering, if they SLOW the rate of energy escaping, what is the residence time of the photon in a CO2 molecule. After finding that residence time is nano to micro-seconds per molecule than another set of questions arose. We will not follow that path.

Since the ERBE and CERES satellites we have been able to sense/measure the incoming and out going radiation. But is the atmosphere opaque to Outgoing Long wave Radiation (OLR)? Not really. If it were we would not have satellites as this: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3b/NPP_Ceres_Longwave_Radiation.ogv/300px–NPP_Ceres_Longwave_Radiation.ogv.jpg

I believe the opaque statement is similar to the “trapped” claim. On a molecular basis, yes, but not so for the atmosphere as a whole. Satellites do sense the OLR.

BTW, for all your ranting about my fantasy world, you have not refuted what I said. You did, however, make a fundamental error: “with the largest cmpoeents of absorption due to CO2 concentrations in he upper atmosphere.” No, it primarily occurs in the denser lower atmosphere where the GHGs are concentrated. The stratosphere is actually cooling, in accordance with the GHG theory.

LT, this statement is also just plain wrong: “… atmospheric CO2 doesn’t absorb most of the IR energy emitted by he Earth…. e.g. refuting the physics of electromagnetic wavelength sensitivity to absorption and transmittance through other molecules, a fact that was scientifically well established already by 1890.”

Earth’s energy budget, simple stated, is the total SW energy received versus the total OLR energy. As I already pointed out, CERES does sense OLR, so most is not absorbed.

You what to see support for climate change “action” drop to nearly zero? Tell people that in order to make a real difference that might actually prevent the world from eventually becoming uninhabitable they will have to give up their cars, malls, suburban homes, vacations, electronic gadgets and consumer products shipped in from all over the globe. Very few people would go along with that–which is why the entire climate change “debate” will never amount to anything more than, ironically, a bunch of hot air.

Karl,

Fully agreed. That’s basically why the IPCC shifted to a broader set of “scenarios” as it became clearer that the rates of fossil fuel consumption weren’t decline, that feed-backs were worse than originally calculated, and gov’ts weren’t going to give up growth much less shift it to efforts to reduce standards of living

the “scenarios” are designed to give gov’ts a way to “delay” the *rate* of warming —- ostensibly to bide more time until we invent a real solution, thereby not taking away hope — a critical necessity. Of course this also gives gov’t an excuse to slow their actual real rate of contributing to reducing fossil fuel use while giving it rhetoric to the contrary.

Besides that the “have” nations are not about to give up their “standards of living” status to let the “have-nots” advance their standards of living… by paying a large part of the price. So the “have not” nations have no reason to comply with doing anything to reduce their contributions to warming, and indeed will continue to use more fossil fuels (since they are lower cost) to try to catch up their standards of living.

Metric Tons Carbon consumption / Capita (2014), for example::

http://cdiac.ess-dive.lbl.gov/trends/emis/top2014.cap

0.47 India

0.49 Vietnam

0.70 Brazil

1.04 Mexico

1.69 13 Major EU nations (excluding France- high nuclear energy)

2.05 China

2.61 Japan

3.24 Russia

4.12 Canada

4.17 Australia

4.43 U.S.

Ands doesn’t even include the African nations or most South American nations.

And then there’s this from the U.S., this week.

https://www.yahoo.com/news/trump-administration-aims-gut-clean-222203128.html

Let’s help US Coal based energy consume more, rather than less fossil fuel. I think this qualifies as another disconnect, though I’m not at all sure it’s a disconnect between the population and their representation in gov’t simply because it reduces or at least mitigates the ncreases in heating and cooling costs, & production costs of goods that use electrical energy.

What consumers say in polls and what they end up voting for are very often (most often?) two different things when their pocket book is affected.

“The Environmental Protection Agency announced on Thursday it will scrap Obama-era rules governing coal ash disposal. The changes would provide companies with annual compliance cost savings of up to $100 million”

“The changes would extend how long the over 400 coal-fired power plants across the country can maintain unlined coal ash ponds and allow states to determine how frequently they would test disposal sites for groundwater contamination.”

CoRev,

Thank-you for clarifying that you don’t have a doctorate and that you’ve never had any of your work even submitted for publication by a credible climate related science peer reviewed journal.

“LT, never said I have a PHD nor have I claimed to have written a paper for a scientific journal. I have said that I’ve studied this subject for years. ”

Do you have a masters degree from a reputable university or college and if so what is the subject field of your masters degree?

If you don’t have a masters degree, do you have a Bachelor of Science degree in a climate related science field?

Just because you don’t have a doctorate and have never been published doesn’t mean you’re wrong or that your conclusions are wrong — it only means that the vast majority credible doctorates in the climate science fields have continuously disagreed with your conclusions.

This also means that they disagree with your understanding of the composite physics of climate science — which doesn’t mean any of your physics is wrong though a few, or some, or many are probably wrong / in error —– but that the vast majority of climate scientists disagree with how you relate various aspects of physics to climate science to draw your conclusions.

I would have to conclude therefore that your belief (emphasis BELIEF) is that the vast majority of doctorates in the fields related to climate sciences are in error, and that you are not in error. Therefore you operate in a fantasy world of your own creation.

You are certainly entitled to your beliefs…. but so are schizophrenics, and creationists and racists and people who believe aliens are controlling their thoughts — it’s just that those people also create their own fantasy worlds out of thin air using the human’s infinite ability to imagine anything.

Don’t misconstrue to think that I’m calling you a nut-case… I’m not. I’m saying only that I find not basis to differentiate.

LT, continuing to argue with yourself? Just which of my CONCLUSIONS do you or science disagree? “Just because you don’t have a doctorate and have never been published doesn’t mean you’re wrong or that your CONCLUSIONS are wrong — it only means that the vast majority credible doctorates in the climate science fields have continuously disagreed with your CONCLUSIONS. ”

You also claim: “I would have to conclude therefore that your belief (emphasis BELIEF)…”

and

“Don’t misconstrue to think that I’m calling you a nut-case..”

You’ve made repeated reference to my fantasy world, my CONCLUSIONS, my BELIEFS actually being out of step with accepted/consensus science.

For clarity, please list those CONCLUSIONS, BELIEFS and define the fantasy world in which I live. Otherwise all you are showing yourself to be a more verbose ideologue and more verbose emoticon as is EMichael. You have also shown that your basic knowledge is lacking and often WRONG.

I readily admit to be a scientific skeptic. I ask questions and do not OFTEN blindly accept without asking those questions.

EM as does LT, continue to argue with yourself? Just which are the “FALSEHOODS” I have written?

My challenge to LT stands for you. Please list the several falsehoods that I have written that you can prove are wrong. If you can NOT, then you are arguing with in the voices in your own head, and not with me.

the pause, among others.

Fighting your library links is a total waste of time, not becuase they are valid, but because you take tiny little pieces and, without any educational background, form a conclusion.

Then, as above, you just want to continue the process. You ever see the movie “guide for a married man”?

Deny, Deny, Deny scene from the movie ‘A Guide For The Married Man’

It is how you “discuss” climate change.

CoRev:

Most people accept the word “trapped” to mean slowed and re-emitting energy in all directions. Energy arrives from the sun in the form of visible light and ultraviolet radiation to the earth. The Earth emits some, most, or all of this energy back into the atmosphere in the form of infrared radiation. Greenhouse gases in the atmosphere capture some of the heat and re-emit it in all directions including back to Earth. Hence, the earth warms up from the presence of Greenhouse gases.

LT:

CoRev will base his obfuscation of Earth Warming upon a word or two and rant on it in many more words as evidenced by his comment. His entire comment does not refute Earth Warming. It is an objection to using a word or two which he takes the meaning literally. Ok LT, you can continue to object to his Earth Warming denial or ignore his earth is flat theory as there is evidence of warming due to Green House gases. I suggest you ignore him.

Run,

I’m quite familiar with CoRev’s argument method — it’s a very common one (also used in format debate, jury trials, and political “discussion”). Throw out isolated disparate points each of which taken alone might make sense, but cannot connect them to make a rational, cohesive argument. Its a subtle form of misdirection — but staying within the subject, It’s most commonly used with public arguments in sciences where 95% of the public have only a 8th or 9th grade understanding of it or none at all.

But I must also admit I’m fascinated by people who use the method and I am very often (too frequently) compelled to play the game — my own failing which I recognize, … a self indulgent entertainment. I apologize for taking up AB’s comment space for doing so.

LT:

Not a problem on your comments. I prefer not to give CoRev too much exposure. He relishes it.

@EM, if the IPCC admits there was a pause why do you deny it? I have kept this graph just for folks like you: http://agw-alarmism.blogspot.com/2017/09/for-those-who-disbelieve-hiatus-even.html

@Run, I agree totally with most of your climate analysis, so why do you misconstrue what I have written? I do, however, not agree with your comment re: ” MOST PEOPLE accept the word “trapped” to mean slowed and re-emitting energy in all directions.” Just refer to LT’s understanding. I also know how hard it is to find the residence time numbers.

BTW, I do not remember denying that Global Warming exists. I have argued for years that ACO2 may not be the main driver. Even the IPCC does not say that ACO2 is solely responsible for all warming.

@LT & EM I see you have yet to find anything (falsehoods, conclusions) to list in my challenge to you, while I have found errors in nearly every statement of yours.

Longtooth,

I am very surprised at your stance on this issue.

From what I have seen of your comments, you seem to be a very independent thinker. You don’t trust appeals to authority and want to figure it out for yourself. You love to debate ideas as a way to figure out truth.

Yet on this issue, Global Warming, oh I’m sorry Climate Change (more flexible) you are slavish to the establishment, even though you could drive a truck through the holes in their argument. Actually you could drive an aircraft carrier through it. You decline to answer any of my legitimate questions. What gives? You should look at some of the dissenting literature ( I gave you some leading dissenting scientists).

Maybe this, along with the data, will give you some understanding of why everyone is not bending over to be carbon regulated.

Sammy, the holes in the theory are being recognized and the scientific knowledge expanded identifying them. It is because of this knowledge they can not refute the finer points mark. Accordingly, as a serious issue it has a hard timne to make the top ten list.

Jeff, framing and messaging, when they are promoting catastrophic impacts from Global Warming/Climate Change (you as is often done interchanged), and when the catastrophic projections/predictions continue to fail. Continued failure and increased knowledge of the weaknesses of the Climate Models will delay any action.

Of course, the real issue is that there are a gang of skeptics in control of the management and purse string, and moderation of the catastrophism should continue.

Sammy, those five scientists are denier clowns. Lindtzen? Spencer” Dear god, just stop.

CR,

Don’t do that cherry pcik thing again.

You spoil the blog.

EM, your lack of knowledge, emotional and apoplectic ranting add nothing to the blog. It is you who spoil the blog.

Why did you ignore the other three scientists Sammy’s article referenced? I doubt seriously that you know of any other skeptical scientists. You do know there are others? BTW, Spencer considers himself a luke warmist.

Or, as Longtooth likes to claim, is your fantasy world just too comfortable to be questioned?

Jeff

maybe you can see from the above the futility of trying to explain climate science to the masses.

but your essay was about framing. i am not sure about this, but i suspect that even with good framing you are not going to get much “do something” from the electorate. first, they have more important (to them) issues on their minds when they vote. second, the whole business of American education is to train people to NOT do something. The “poorer” students are told they are not smart enough. The Harvard students are told they are too smart and don’t have to actually think about anything in order to know the right answer… which does not involve doing anything.

On the other hand, there does seem to be a good bit of activity at the state, city, and local levels.