Initial jobless claims: the single most positive aspect of the entire economy

Initial jobless claims: the single most positive aspect of the entire economy

WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 21, 2018

Conflicting reports on the “rental affordability crisis”

– by New Deal democrat

About half of renters spend more than 30 percent of their income on rent, up from 18 percent a decade ago, according to newly released research by Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies. Twenty-seven percent of renters are paying more than half of their income on rent.

This is a serious real-world issue. I have been tracking rental vacancies, construction, and rents ever since. The Q4 2017 report on vacancies and rents was released a few weeks ago, so let’s take an updated look.

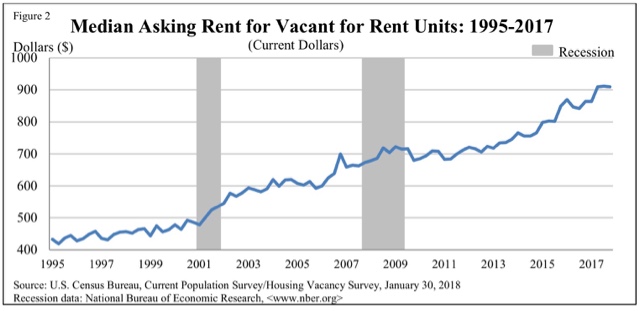

In the second quarter of last year, median asking rents zoomed up over 5% from $864 to $910. In the two quarters since, they have remained at that level:

Here is an updated look at real. inflation adjusted median asking rents, showing that rent pressures on household budgets continued to rise in 2017:

| Year | Median Asking Rent |

Usual weekly earnings |

Rent as % of earnings |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | 330 | 382 | 86 | |

| 1992 | 401 | 437 | 92 | |

| 1993 | 422 | 450 | 88 | |

| 2000 | 478 | 568 | 84 | |

| 2002 | 545 | 607 | 90 | |

| 2004 | 599 | 629 | 95 | |

| 2009 | 680 | 739 | 92 | |

| 2012 | 717 | 768 | 93 | |

| 2013 | 734 | 778 | 94 | |

| 2014 | 762 | 791 | 96 | |

| 2015 | 813 | 809 | 100 | |

| 2016 | 859 | 832 | 103 | |

| 2017 H1 | 887 | 860 | 103 | |

| 2017 Q3 | 912 | 866 | 105 | |

| 2017 Q4 | 910 | 854 | 107 | |

The big increase in unaffordability is unfortunately of a piece with the rental vacancy rate which, after appearing to have bottomed in 2016, tightened again in this report:

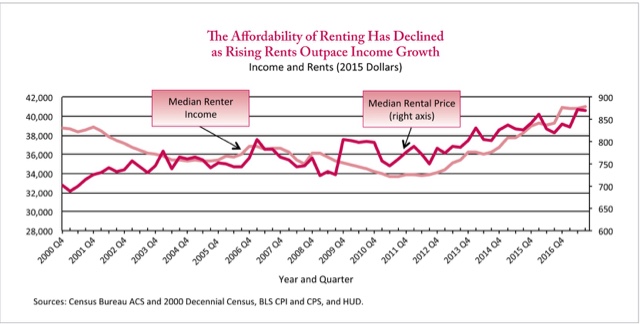

Like the median household income data, this shows renters’ income bottoming out in 2011-12, and rising since relative to rents as calculated by the ACS.

.

NDD

On Initial Jobless claims:

By your measure of relative initial claims (and mine using Civilian Labor Force as the denominator and 4 week moving average Initial Jobless Claims ) it is well below any prior history.

By my measure (% of Civilian Labor Force) it’s 0.15% against the last two pre-recession minimums of 0.2% and most of the minimums preceding those of from 0.22% to 0.25%.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/fredgraph.png?g=iGgu

Since Jobless Claims are an indicator — e.g. a dependent variable — Have you done any analysis to show why it’s so low????

I haven’t done so myself but will only remind that when-ever the jobless claims rate reaches a minimum (by definition the minimums occur when preceding onset of recession) it indicates a stress in the economy that can’t be sustained… e.g. excessive stress.

In the last two recessions the minimums (% of Labor Force) occurred from 12 months to 18 months prior to official recession onset. This is NOT intended to imply that the current low IS at the pre-recession minimum, but only that it is approaching it..

In other words the levels of current jobless rate being 25% below the prior two lows at 0.2% (which were lower than any before that) seems to me to be a cautionary tale of the state of the economy, rather than one which indicates the economy is poised for growth.

What do you think?

Longtooth; re: Have you done any analysis to show why it’s so low????

have not most states tightened their standards as to who can claim? i can’t put my finger on it, but it seems there were a lot of compaints to that effect several years back..

NDD,

One of the stresses I’ve mentioned in a prior comment to you on one of your other resent posts is the personal savings rate which was near the all time low as of Oct 2017 (latest FRED data point) at.3%. There are 3 months since then where we have no data yet. I would expect those three months to be material on personal savings rate stress one way or another…. especially since they include the holiday spending spree period.

This compares to 1.9% in Jul 2005 and 2.5% in Nov 2007 a month prior to onset of the Great Recession.

In the 2000 Dot-com recession the low 4 months prior before was 3.5% in Dec 2000.

Another stress factor are real average hourly earnings of production and non-supervisory employees (60% of employment).

Hourly Earnings in Jan 2018 it was down 0.5% from Dec 2017

Weekly Earnings were down 0.8% from Dec.

Jan 2017 to Jan 2018 Weekly Earnings were up a paltry 0.2%

From BLS:

” Real average hourly earnings for production and nonsupervisory employees decreased 0.5 percent from December to January, seasonally adjusted. This result stems from a 0.1-percent increase in average hourly earnings offset by a 0.6-percent increase in the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners

and Clerical Workers (CPI-W).

Real average weekly earnings decreased 0.8 percent over the month due to the decrease in real average hourly earnings combined with a 0.3-percent decrease in average weekly hours.

From January 2017 to January 2018, real average hourly earnings increased 0.1 percent, seasonally adjusted. The increase in real average hourly earnings combined with no change in the average

workweek resulted in a 0.2-percent increase in real average weekly earnings over this period.”

https://www.bls.gov/news.release/realer.nr0.htm

I will point out however that nominal weekly and hourly earnings are notoriously volatile on a month to month basis, varying fro -0.1% to +0.6% month to month and there’s no discernable recent trends, so any trends in real hourly earnings would be based on inflation rates..

On a CPI-U inflation adjusted basis (2016 = 1) from Jan 2016 to Jan 2018, I note that the Inflation adjusted wage (production and non-supervisory) has dropped from a high o $21.495 in July 2017 to it’s present low in Jan 2018 of $21.331 or by -0.76%.

So the inflation adjusted wage has gone steadily south for the last 7 months (Dec 2017 it was up $0.04 before dropping by $0.09 from Dec to Jan.

If anything this 7 month production and nonsupervisory inflation adjusted wage trend has put more stress on the economy rather than less.

NDD,

I should also add that the international value of the dollar is at or near half of the increase from 2014 to the average value it was for nearly 3 years prior to Trump’s inauguration (~20% increase)..

This increases import prices which increases consumer’s costs thus contributing to inflation though on a considerably lagged basis due to long term (3 mo., 6 mo., & 1 year) contracts.

Finally residential housing completions have been steadily declining on an average annual basis since 1968 to present. It’s been increasing steadily since the low in 2011 and is now finally (2017) back near the trend line. It should go higher than the trend before reversing again but will not get anywhere near the highs reached in 2002 to 2006.

But with the increasing interest and mortgage rates and Trump’s new tax plan its not likely to climb much beyond trend in 2018, which is to say not much beyond the rate it last was at in 1996/97 (excluding the bubble years 2002 – 2006).

In other words don’t look to housing construction to contribute much to employment in 2018.

NDD,

Since the initial claims are a function of unemployment, I checked the relationship to see if initial claims drops as a percentage of unemployment — as one might expect.

And it’s true. Historically the trend is down — initial claims drops as a percentage of overall unemployment.

What occurs in the cyclic data however is that initial claims increases as percent of unemployment from lows after a recession to the point at which the next recession begins.

That cyclic trend is also the case at present — initial claims have been increasing as a percentage of unemployment..

Simply stated relative to the number of people unemployed there are now more, not fewer, initial claims (4 week moving average) As fewer people are unemployed then a greater proportion of them file for Unemployment Insurance claims.

This means that while absolute numbers of claims decrease their relative proportion of unemployment INCREASES between recession cycles. This is also the overall trend from 1968. The recent data is consistent with the overall trend… though there are also other factors.

One of those factors is that the proportion of low skill/low wage jobs relative to employment has been decreasing in historic trend, but since claimant profiles show ~ 2/3’s of claims are by low skill/low wage labor, then one would expect the number of initial claims to be decreasing as a function of total employment.

In other words a skills demographics of employment is most of the reason for the 25% reduction in current initial claims as a percentage of employment relative to the prior two recent low points. preceding the dot-com and housing bust recessions.

NDD,

Sorry I forgot to link to the FRED data showing the relationship of initial claims (4 week moving average) to unemployment.

NDD,

For some reason the FRED link isn’t showing up in comments.

The data I used is a/(b*1000) where:

a = initial unemployment claims number (4 week moving average)

b = thousands of unemployed.