Output Optimum and the Roller Coaster of Immiseration

Following up on my post from two weeks ago, Immiseration Revisited, I built a spreadsheet replica of the marvelous Chapman diagram. In addition to lines on the page, the replica provides me with tables of numbers that I can add, subtract, multiply and divide in accordance with the conceptual logic of the diagram.

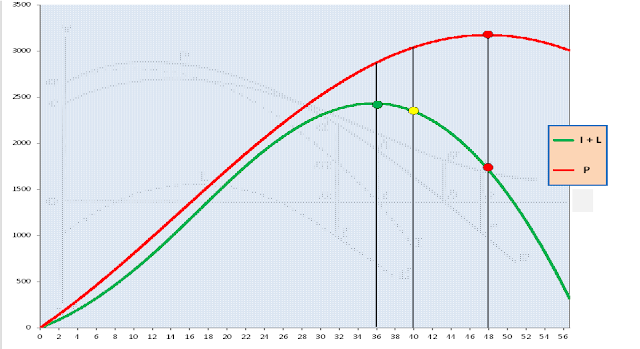

The chart below shows the results of some of these calculations. The red curve graphs cumulative gross “output” and green curve subtracts the value of foregone leisure and the pain cost of fatigue and wear and tear from output to calculate net “income” (green). The length of each vertical line measures the values of output and income, respectively for a work week of the length indicated by the scale on the x-axis.

|

| “Big Dipper”: the Roller Coaster of Immiseration |

I have set the hypothetical “output optimum” work week at 48 hours in deference to the diagram’s 1909 vintage. Assuming such an optimum and taking the conceptual diagram’s proportions literally, the ideal length of a work week for a laborer would be 36 hours. That is the point at which the value of foregone leisure and the pain cost of additional work begin to outweigh the additional earnings from the longer week. A workweek of 40 hours marks the threshold beyond which the value of foregone leisure alone exceeds the additional wage earnings.

If the optimal output workweek was 40 hours, the corresponding ideal length of workweek for the worker would be 30 hours, again assuming the reasonableness of the diagram’s proportions. There is, of course, only impressionistic evidence for the general shape of the curves and not for the accuracy of the proportions depicted. Nevertheless, the derived calculations indicate a steep acceleration of the discrepancy between output and worker welfare beginning well in advance of the output optimum.

Calculations based on the diagram suggest that by working 34 percent more hours per week, the employee can look forward to “enjoying” 29 percent LESS net benefit. If the actual cost to workers of working longer is even half or a third of those estimates, this still would represent a significant deviation not only from what Lionel Robbins dismissed as “the naïve assumption that the connection between hours and output is one of direct variation” but also from the equally indefensible premise of a consistently proportional relationship between work effort and reward.

(Most) Economists Balk

In a recent article, “Whose preferences are revealed in hours of work,” John Pencavel noted the “radical change in economist’s thinking about working hours” following the 1957 publication of H. Gregg Lewis’s article, “Hours of Work and Hours of Leisure,” Earlier textbooks attributed reductions in hours to pressure from trade unions, either directly through collective bargaining or by legislation promoted by organized labor. The earlier textbooks also addressed the effect that hours of work have on productivity, with reductions in hours usually leading to increases in hourly output and sometimes even to “no decline in total daily output.”

In later textbooks, the orthodoxy followed Lewis’s explanation that workers choose their own hours, based on their preferences for income or leisure. The connection between output and shorter hours vanished, as did the role of trade unions in achieving reductions of working time. But, Pencavel wondered, “If ’employers are completely indifferent with respect to the hours of work schedules of their employees,’ [as Lewis had posited] why did employers oppose so resolutely workers’ calls for shorter hours?”

In a footnote, Pencavel also mentioned that in Lewis’s 1957 model, employers face no obstacle “to replacing shorter hours per worker with more workers.” This is an interesting point because many economists’ arguments against the employment potential of shorter working time rest on claims that workers and hours are not suitable substitutes. That conclusion is reached by smuggling back in the output/hours relationship concealed in a Cobb-Douglas production function with the Robbins/Hicks “simplifying assumption” that the current hours of work are optimal for output, so that any reduction of hours would result in a reduction of output. It is difficult to imagine how both of these things can be true at the same time.

Although the earlier textbooks and economists acknowledged the connection between hours of work and output, most were silent on the discrepancy — or at least the magnitude of the discrepancy — between an output optimum and worker welfare. Cecil Pigou, Philip Sargant Florence, Lionel Robbins, John Hicks and Edward Denison treated the output optimum as the economic ideal. Richard Lester and Lloyd Reynolds, authors of “institutionalist” labor economics textbooks, showed more sympathy to trade union arguments but did not emphasize the discrepancy between the output optimum and worker welfare.

Sydney Chapman clearly distinguished analytically between worker welfare and the output optimum but his presentation was obscured by digressions that dwelt on shift-work as a palliative and on the philosophical necessity of paying more attention to the non-tangible aspects of culture. Clyde Dankert clearly distinguished between the output optimum and worker welfare but had the rather eccentric view that although “maximization of worker satisfactions” rather than output should be the social objective, shorter hours would have to be postponed “in view of the current cold war situation.” Only Maurice Dobb clearly and concisely stated what was at stake (although he left out the increasing value of leisure):

…trade unionists in the nineteenth century were severely castigated by economists for adhering, it was alleged, to a vicious ‘Work Fund’ fallacy, which held that there was a limited amount of work to go round and that workers could benefit themselves by restricting the amount of work they did. But the argument as it stands is incorrect. It is not aggregate earnings which are the measure of the benefit obtained by the worker, but his earnings in relation to the work he does — to his output of physical energy or his bodily wear and tear. Just as an employer is interested in his receipts compared with his outgoings, so the worker is presumably interested in what he gets compared with what he gives. A man who works longer hours or is put on piece-rates, and increases the intensity of his work as a result, may earn more money in the course of the week; but he is also suffering more fatigue, and probably requires to spend more on food and recreation and perhaps on doctor’s bills.

To compare “what s/he gets” with “what s/he gives” requires above all some way of estimating the value of what is given relative to what is being received. One may even suggest that constructing those estimates was the job economists should have been doing instead of castigating trade unionists and other advocates of shorter hours for adhering to a vicious “lump-of-labor” fallacy. Heck of a job, economists!

I’d be interested in anything that would help make these numbers more concrete.

It’s easy to say that different individuals (with their different physical and mental strengths) doing different types of work (knowledge vs physical labor) have different tolerances for additional hours. However, at aggregate levels, there are national “laboratories” where people generally work different numbers hours per week, at least on an annual basis (this is a real complicating factor, in some of the European countries with “shorter work weeks” there is an actual (contractual) trade-off between working longer than standard weeks (usually working 40 instead of 30-something hours), and then getting additional “vacation” days).

That’s perhaps another area for investigation, the value in continuity of labor and leisure time. There’s definitely some information out there on full flex labor (certain companies within fast food and retail, where workers are effectively on-call for an employer, but can only expect part-time work).

Is it better to work 7.2 hours per day, or is it better to work 8 hours per day, and get two extra days off per month (24 days)? Is it better to get four more weeks of vacation (20 days) that you can use contiguously than it is to have a one day shutdown every other week (26 days)?

How does this operate for different age groups? It’s fairly typical for companies and the government to reward years of service with additional days of vacation. If companies have designated or unlimited sick time, does that offset the negatives to employees of routinely working more hours? What about the trend in knowledge companies to encourage people who are sick to work at home?

The reality of labor is insanely complicated in 2017.

In part, that is what this post is about. Back in the 1960s, Edward Denison, one of the pioneers of economic growth accounting, lamented the paucity of data that could “make these numbers more concrete.” Very little has been done to expand the basic data collection and mainstream economists have been complacent about pursuing research programs that would use such data, presumably because they figured the labor-leisure choice model told them all they needed to know.

But, on the other hand, “you don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.” It is not “prudent” to look at these hypothetical results and demur, “gee, I wish we had some hard data.” It is complacent and hypocritical. There is no evidence for lots of things in economics that are taken for granted — one of them being the labor-leisure choice model!

Put more clearly: I wish we had some better numbers so we could formulate and justify a strategy to balance the desires of employers and employees via a legal, regulatory, or “boots in the streets” approach.

Capital holders are currently winning. Managers are currently winning. Companies in many cases are not winning (except top management). Employees are losing.

However, the social optimum may well not be the employee optimum, anymore than it is the output optimum. Reading the chart, and assuming that the numbers there are reflective of reality, the 40 hour workweek doesn’t seem unreasonable. If there is a better point, it is probably effectively a nudge, not a full day reduction in the workweek, which probably makes it a marginally tougher sell. I would have trouble telling the difference between a 36 and 40 hour workweek, and I suspect that I would still be working the 40-50 that I work now, even though contractually and notionally I am not getting any extra money because I’m salaried.

I am legitimately interested, however, in whether a mandatory paid 45 minute lunch could be implemented.

I assumed a 48-hour output optimum week in tribute to the 1909 vintage of Chapman’s diagram. Research during WWII concluded that a 40-hour week would be optimal for output. Assuming a 48-hour week in 1909, a 40-hour week in 1944 and continuation of the trend, on a percentage basis would suggest an output optimum week of 27 hours in 2017, which implies something like a 20-hour week as ideal for worker welfare.

At first sight this may appear rather preposterous. But if we extend the analysis from worker welfare to ECOLOGICAL sustainability, maybe not so outlandish. Elsewhere I have made the argument for treating labor power as a common-pool resource, thus making possible the treatment of other common-pool resources (forests, fisheries, ground water & stream flow, arable land, atmosphere etc.) as analogous to labor.

The way things are configured currently, a tremendous amount of output is WASTE. My guess would be about 85% is devoted to “positional consumption,” which is a fancy name for waste.

When you have only a 20 hour work week, it gets hard to justify working in a lot of scenarios. I drive an hour to work. I’m not driving an hour each way to work 4 hours. Suddenly you are talking about a need to radically reconfigure the workforce to make that work, unless they’re working three day weeks. 20 to 24 hours with a 3 day employee workweek and a 6 day employer workweek is manageable, but then the questions of whether the work day needs to be shorter rather than the week become important.

Many people who work in urban areas are in similar situations. I drive to work, from an urban suburb to a rural suburb, and cross-downtown (not a great drive, but better than the belt route), but if I worked downtown, and took the subway, I could also count on a 40 minute+ commute most likely. There are also substantial ramps and start/stops and demand peaks in office work and service work.

It’s super complicated.

JG:

You would work the 4 hours for the same pay.

Run, assuming you mean “at same pay” meaning same purchasing power pay.

For the “its complicated” comments I take it to mean that this is “too complicated” to fix or deal with. But so is was nuclear physics, relativity of time and space, or for that matter political economy or justice or race relations.

Because “it’s complicated” is no excuse for not pursuing a greater and better understanding from which then comes a greater and better set of choices that have bearing on realities (rather then made-up versions there-of). Its called making progress I think in general terms.

Isn’t the labor v liesure question actually a matter of whether one has the choice to chose how much of each to utilize when the urge for one or the other strikes?

I note that history shows as far back as we have any records and solid archological evidence, that the wealthy chose more liesure time than labor time. From this and present observations it is apparrent that humans desire the optioin of whether and when to use their labor for some productive ends and whether and when to use liesure pursuits for no necessarily productive ends.

Now in-as-much as those with wealth have the choice it’s only because their other material needs for life are supplied by the labor of others from which the wealthy extract a proportion to suit themselves. They can do this, and always have done this, becaus they control the state fo the then societal form of civilization … either directly by force and policing power or by inhereted agreement (devine right, democratic policies, etc.), Pure luck of circumstance, who you befriended or impressed, what you inhereted, your verbal communications skills (some inhereted, some learned) all made the difference between wealth and non-wealth.

Simply put, the wealthy have the power to exploit those without it to their own benefits. This gives them the choiice betwen expending their time to maintain and/or enhance that wealth and power or use it for liesure. Those they are exploting do not have that choice. This is the essense of the liesure v labor time issues and questions.

Thus as I understand the question and issue its simply a matter of how much those with the power and wealth are willing to give up some of that wealth, and perhaps even some of their power, by exploiting those without it less than they are now able to exploit them.

The essense of the issue raised by Sandwichman is whether there is a more optimal level of exploitation in labor’s use of time, to which he then also includes optimal use of nature’s resources … meaning sustainable levels to be used ad-infinitum by future generations.

In othe words he’s addressing a far greater question than just optimal work hours v liesure time for labor for net constant or improved returns to labor’s output for the exploitable use by those with wealth and power (e.g. capital owners). He’s addressing a fundamental question of human civilization on this globe and how it should be or must be modified to sustain it without (reading between the lines) war, civil war, massive insurrection, revolution, or pure police state forms of society. I’m not at all sure that Sandwichman actually knows that this is what he’s actually addressing, but I surmise that it is …. at least in large part.

The only reason this seems to be “complicated” is that he’s limited the issue to specifics in the here & now levels of exploited labor and that in so doing it doesn’t direclty include the actual factors that are at issue… perhaps because the real issue is far more than can be addressed in a few simple short posts addressed to the variety of readers attending Angry Bear.

So what Sandwichman is doing in his posts on the subject is pursuading or attempting to pursuade some readers at least that there are other options available than the status quo which will serve labor’s interests more than they now do and thus also perhaps serve the exploiters’ interests at the same time.

Where I differ with Sandwichman, if at all, is that I believe the fundamental issues have to address the levels of exploitation by wealth, which is also to say the power they have in making law that give them the power to continue to exploit. However, I do not find fault with Sandwichman’s endeavors to pursuade under the realities of the way things are…. i.e. in the present tense nature of the status-quo system of civilized societies.

Finally I will also say that I’m not at all convinced we humans will ever figure out how to sustainably survive without fighting among ourselves for power and resources, hence wealth and privelage .. it seems to be historically purvasive in our species…. which will also be our species demise at some future point in time. We simply can’t self regulate for our own benefits as a species. Apparently, my guess, is that our evolutionary roots are part and parcel of what we call ourselves (human beings). We are what we are. We can change under duress and when circumstance give us no other options, but that isnt’ by choice.