Liberals Getting it Wrong on the Job Guarantee

I’ve been quite troubled lately by voices I’ve been hearing from my compatriots on the Left discussing the Job Guarantee — especially in relation to an alternative, Universal Basic Income. A new Jacobin article by Mark Paul, William Darity Jr., and Darrick Hamilton displays several of the aspects that make me uncomfortable.

Get the Math Right. Right off the bat, I’m troubled by the article’s flawed arithmetic — not what I would like to be seeing from left economists who need to be scrupulous in their role as authoritative voices for the left.

…we argue for a FJG that would pay a minimum annual wage of at least $23,000 (the poverty line for a family of four), rising to a mean of $32,500. … In comparison, many of the UBI proposals promise around $10,000 annually to every citizen…half the rate that would be available under the FJG.

$10K per citizen versus $23K per worker is not “half the rate.”

How do the two policies actually compare? I have no idea. This is exactly the kind of difficult calculation that we need economists to do for us (it’s way beyond our abilities), so we can evaluate different policies. Absent analysis with clearly stated parameters (Who counts as a citizen? Children? Etc.) this kind of statement carries no import or information value.

These analyses have been done by economists. I’ve seen them around. But I don’t have them to hand; they’re exactly what I’d like this article to point me to. Are these authors unaware of this work, or did they just not bother to look at it, draw on it, or cite/link to it in this article?

Perhaps most important: this kind of slipshod analysis delivers live and loaded rhetorical ammunition to the enemy. It’s an invitation to (very effective) hippie-punching.

Get outside economists’ fetishistic obsession with short-term business cycles, and with the automation versus globalization debate. We’re facing decades-long campaigns to get any JG or UBI implemented, and decades- or centuries-long technological and job-market trends. If Ray Kurzweil’s exponential productivity growth is even somewhat valid (choose your exponent), we’re facing at a world where Star Trek-style replicators can turn a pile of dirt into a skyscraper or a thousand Thanksgiving dinners — and potentially, where a small handful of people own all those replicators.

In this world, nobody would ever pay a human to produce goods. It would be stupid. Will service work deliver the kind of jobs and wages that let a worker share the fruits of that spectacular prosperity? It doesn’t seem likely. Will the highest-paying service jobs themselves be automated? It seems likely.

That’s an extreme vision, but it embodies the long-term issues these policy discussions need to address. Instead we get from the authors:

The dangers of imminent full automation are overstated…. No doubt, stable and high-paid employment opportunities are dwindling, but we shouldn’t blame the robots. Workers aren’t being replaced by automatons; they are being replaced with other workers — ones lower-paid and more precariously employed.

They’re pooh-poohing the technological future — continuing centuries of Luddite-bashing — because (quoting Dean Baker):

In the last decade, however, productivity growth has risen at a sluggish 1.4 percent annual rate. In the last two years it has limped along at a pace of less than 1 percent annually.

Issues here, in very short form: 1. Productivity and “economic capacity” measures are wildly problematic, both theoretically and empirically. The econ on this is a mess. 2. A decade, much less two years, is not even close to a trend. 3. The automation vs offshoring debate is specious; they’re inextricably intertwined, like nature and nurture. 4. They’re (I think unconsciously) buying into the whole economic worldview and conceptual infrastructure (think: “factors of production”) that delivered us unto these times.

The authors are certainly correct that:

…the balance of forces over the last few decades has been skewed so dramatically in the favor of capital. … It’s time to get the rules right

But this fairly muddled (and hidebound) depiction of the issues at hand does little or nothing to suggest what the new rules should be. We need left economists to unpack these long-term secular forces and trends far more cogently — and radically. They need to be examining the very foundations of their economic thinking and beliefs.

The “Dignity of Work.” It actually makes me squirm in discomfort to hear liberals with very cool, interesting, high-paying jobs going on about the dignity of work. I’m just like, “how dare you?” That kind of supercilious presumption arguably explains why liberals have been losing elections for decades — especially the latest one.

Here’s the full passage on this:

Conventional wisdom holds that people dislike work. Introductory economics classes will explain the disutility of labor, which is a direct trade-off with leisure. Granted, employment isn’t always fun, and many forms of employment are dangerous and exploitative. But the UBI misses the way in which employment structurally empowers workers at the point of production and has by its own merits positive dimensions.

This touches on a heated debate on the Left. But for now, there is no doubt that people want jobs, but they want good jobs that provide flexibility and opportunity. They want to contribute, to have a purpose, to participate in the economy and, most importantly, in society. Nevertheless, the private sector continues to leave millions without work, even during supposed “strong” economic times.

The workplace is social, a place where we spend a great deal of our time interacting with others. In addition to the stress associated with limited resources, the loneliness that plagues many unemployed workers can exacerbate mental health problems. Employment — especially employment that provides added social benefits like communal coffee breaks — adds to workers’ well-being and productivity. A federal job guarantee can provide workers with socially beneficial employment — providing the dignity of a job to all that seek it.

The variations on the “dignity” thing are endless. Our authors here give us:

employment structurally empowers workers at the point of production

This is clearly something that working-class workers and voters are clamoring for.

by its own merits positive dimensions

Sure: in our current system where only wage/salary work provides “dignified” income, you’re gonna see positive second- and third-order effects from employment. Does a program where government provides the income (in most implementations, channeled through private-sector employers) change that pernicious social environment?

But wait: workers get communal coffee breaks!

The whole thing actually, rather remarkably, turns Marx on his head. The alienation that he imputes to working-for-the-man, wage labor is here transformed into the sole, primary, or at least necessary source of human dignity and self-worth. It’s the only way for the working class “to contribute, to have a purpose, to participate in the economy and, most importantly, in society.” Contra David Graeber, if there’s not a money transaction involved, it’s not “valuable” or worthy.

This before even considering the freedom to innovate and thrive that arises when you don’t have to go to work. (Every startup I’ve ever been involved in — many — began with endless hours of hanging out and drinking beer with friends.)

Like so much so-called left thinking over the last half century (think: The Washington Consensus), this thinking unquestioningly, even blindly, unconsciously, adopts and is entrapped by one of conservatism’s core economic mantras: “incentives to work.”

Why in the hell do we want people to work more? We know why conservatives do: because it allows rich people to profit from that labor and grab a bigger piece of a bigger pie. But isn’t the whole point of increasing productivity (or a/the main point) to work less while having a comfortable and secure life?

What the authors dismiss as “conventional wisdom” is in fact largely correct: Most people don’t want to go to work. Or they don’t want to work nearly as much as they do. They can manage their “relationships” and social well-being just fine, thank you. Sure, they enjoy the social interaction at work, to the extent that… But they go to work because they want and need the money. Full stop.

In 1930 Keynes predicted a future of 15-hour work weeks. Sounds idyllic to me. Does anyone think workers would object? Or do we have a better handle on their wants and needs than they do?

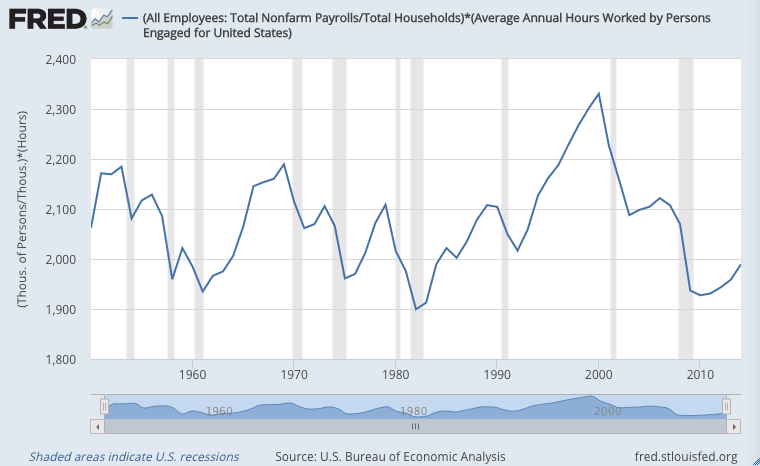

We haven’t even come close to that future. Two-earner households are now the necessary norm, and hours worked per worker has been flat since — surprise — 1980, after a very nice decline postwar. Here’s annual hours worked per household, even as households have gotten steadily smaller:

A job guarantee as I understand it does nothing to advance that Keynesian bright future. Given the pro-work rhetoric we hear from JG enthusiasts, it might just further entrench what you see above.

So three takeaways here:

• Get the math right. Do the careful, difficult analysis for us so we can make informed judgments. Or point us to the work that’s already been done.

• Look to your theoretical and empirical fundamentals. They’re often inherited, often unconsciously. They’ve been indoctrinated and inscribed into economists’ invisible System 1 thinking. Many of them are not conceptually coherent, or morally valid.

• Just stop talking about the “dignity of work.” It’s a huge own-goal — both the policy results (more work for workers), and the electoral results of that presumption.

If we want that Keynesian utopia — comfortable, secure lives with not a lot of work required — UBI seems like a far more direct path to getting there. If you want to give people comfort, security, dignity, well-being, power, the opportunity to thrive on their own terms, and economic security…give them money.

Cross-posted at Asymptosis.

I agree, jobs aren’t the issue. There are more jobs now, than in the 60’s boom. My father was laid off from a mill in 67, it wasn’t easy to find a job. Though, when you did, the security was greater than today. I think this is where the mistakes are made in analysis.

I agree with the author. I sometimes wonder what the number in guaranteed income I would take in order not to work. I think about 3-4K per month would do it.

But then I would worry about the pathology of sitting around all day with nothing but time on my hands. I would like to think I could handle it but the evidence from lottery winners down to welfare families is not encouraging.

I once took a class where the prof sat the students in a circle with absolutely no task or guidance. Shortly the students began (verbally) ripping each other apart, forming factions, and basically bringing out the worse in each other. This is also known as an “encounter group.”

One of my takeaways from this is that humans need a task, lest they start attacking each other for no good reason, just one invented by their idle mind.

Sammy, take guitar lessons. Also, walks in the sunshine are nice.

Here we go loop-te-loo …

… job guarantee …

… here we go loop-te-la …

… universal basic income.

Anybody ever hear of labor unions …

… ask Germany; ask Jimmy Hoffa.

First things first …

… if Walmart (that is consumers) can pay $20-25/hr for stacking shelves) …

anybody aware that labor is bought and sold sort of on margin; that if Walmart labor costs are 7% that a big increase in wages would only cause a small increase in prices and consequent loss of sales …

… and Walmart is not paying that, that should be our first and foremost concern (ask Germany).

ACTUALLY, if today’s lower wage earners got wage increases across the board — they would spend proportionately more of it at lowest wage businesses — very possibly leading to MORE sales. What happens when you sell fewer potatoes for more overall money — but the potatoes keep, and spend, the money. 🙂

[snip]

THE MONEY IS THERE SOMEWHERE

You can’t get something from nothing but, believe it or not, the money is there, somewhere to make $10 jobs into $20. Bottom 45% of earners take 10% of overall income; down from 20% since 1980 (roughly — worst be from 1973 but nobody seems to use that); top 1% take 20%; double the 10% from 1980.

Top 1% share doubled — of 50% larger pie!

One of many remedies: majority run politics wont hesitate to transfer a lot of that lately added 10% from the 1% back to the 54% who now take 70% — who can transfer it on down to the 45% by paying higher retail prices — with Eisenhower level income tax. In any case per capita income grows more than 10% over one decade to cover 55%-to-45% income shifting.

Not to mention other ways — multiple efficiencies — to get multiple-10%’s back:

squeezing out financialization;

sniffing out things like for-profit edus (unions providing the personnel quantity necessary to keep up with society’s many schemers;

snuffing out $100,000 Hep C treatments that cost $150 to make (unions supplying the necessary volume of lobbying and political financing;

less (mostly gone) poverty = mostly gone crime and its criminal justice expenses.

IOW, labor unions = a normal country.

[snip]

Instead of speculating on science fiction-alternate history futures, why don’t we take care of the most unfinished business of today: 6% private firm labor union density?

“…wage labor is here transformed into the sole, primary, or at least necessary source of human dignity and self-worth…”

Certainly, from the 60s onwards this has been the concept of work and worth. It’s been pushed by business and their supporters in the right wing, together with its converse — that if someone cannot find paid work and be glad of it, however poorly paid, then they have no worth.

The implication, never talked about, is that the so-called job creators are the sole dispensers of social worth. Some pundits have gone so far as to say that family duties are to be undertaken in people’s spare time, and that they shouldn’t have children if they don’t have a steady income.

At the same time, another idea has been widely spread — that those job creators have no responsibility to workers, citizens or society aside from their solemn duty to make a profit for their business — that is, to take in more than they give out.

Put them together, and it is no wonder that people should be filled with either depression or anger. Not only do the job creators choose who is worthy, but even who can reproduce.

Despite citizens’ best efforts, they have no guarantee that those efforts will win them any respect or stability in their lives. Business may talk about the dignity of work, family, parenting, honesty, and caring for their fellow citizens, but there is nothing in business policy that supports those noble things, except if forced by law, regulation, or public opinion voiced on a grand scale.

Yet the existence of a stable, mutually supportive society is what makes most businesses possible, much less profitable.

Noni,

great comment.

By the way, I have a simple name for the job guarantee, paternalism.

If a job guarantee is paternalism, what do you call Universal Basic Income, an “allowance”?

@Warren: I’d call it an effective and efficient necessary corrective to capitalism’s inexorable tendency to concentrate wealth, thus strangling both itself and us.

Except that there is no such “inexorable tendency” of capitalism, Steve.

@warren:

You just keep telling yourself that. History, and arithmetic, suggest otherwise.

In the U.S., at least, the one long trend suggesting otherwise started in 1933, and was the result of: 1. The New Deal, 2. Massive government deficit spending in WWII, and 3. Massive transfer of real buying power from creditors to debtors from postwar inflation.

So yeah: that concentration is not inevitable. It can be counteracted, to deliver far greater and wider prosperity and economic growth.. But absent intentional efforts to do so, it is inexorable.

Love to hear an answer to the core question posed here:

Why hasn’t it happened? Not even once?

It hasn’t happened because politicians get elected by promising to give a lot of people the money of the few. It’s not that it hasn’t happened because it cannot happen, but that it hasn’t happened because it has never been tried.

Get real. Politicians get elected by kneeling and servicing big donors. Making wealth concentration even more of an inexorable, self-perpetuating cycle. Republicans have been winning for decades while promising (and delivering) no or less giveaways! That’s the historical reality.

Again it can be intentionally counteracted, but the inherent dynamic means it’s only happened once in the US, in response to The Great Depression that was caused by that wealth concentration. (Despite Teddy Roosevelt’s best efforts.)

If politicians were “elected by kneeling and servicing big donors,” Clinton would be president now.

Nevertheless, centralizing power in the government does indeed “[make] wealth concentration even more of an inexorable, self-perpetuating cycle,” which is why I oppose putting more power in the hands of the government.

What actually happens is that the big donors just buy whoever happens to be in office at the time. Giving more and more power to the government only makes the purchase of politicians more cost effective.

The Great Depression wiped out that wealth concentration you say caused it, thus proving my point that such wealth concentration is not inexorable. Thank you.

> The Great Depression wiped out that wealth concentration

Are you really that completely unfamiliar with the actual evidence and data?

It took half a century after 1929 for that wealth concentration to decay, a process that ended in — surprise — 1980.

@warren:

But I’m sure you know this:

The New Deal, massive wartime deficit spending, and truly massive inflation-driven postwar buying-power transfer creditors->debtors were followed by…the greatest burst of widespread prosperity and economic growth in U. S. history — before or since.

Just a coincidence, I’m sure.

“It took half a century after 1929 for that wealth concentration to decay, a process that ended in — surprise — 1980.”

Please show us the data for that assertion.

“The New Deal, massive wartime deficit spending, and truly massive inflation-driven postwar buying-power transfer creditors->debtors were followed by…the greatest burst of widespread prosperity and economic growth in U. S. history — before or since.”

To a great extent, yes. Without the economic destruction of the Great Depression and two World Wars, there would have been no post-war boom.

>Please show us the data for that assertion.

As I suspected.

Let me Google it for you:

https://www.google.com/search?q=piketty+1%25+wealth&espv=2&biw=1277&bih=632&site=webhp&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj3jJuoiLvSAhVSw2MKHYYyCKMQ_AUICCgD#imgrc=MQs5bx8XAUcXNM:

> Without the economic destruction of the Great Depression and two World Wars

Wealth destruction in the U.S. in WWII? The country got vastly wealthier!

Now that you know the facts, gonna change your beliefs any? Or keep clinging to them?

That’s brilliant, Steve! Picketty’s data show you are WRONG! Wealth ownership of that top 0.1% was FLAT from 1948 through 1968!

So much for that post-war wealth transfer.

Are you suggesting that we just spend a shit-ton of borrowed money on defense spending like we did in WWII to make the country wealthier? Try selling that one!

(BTW, I highly recommend you read Thomas Picketty’s book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Despite his faulty premise (using the wrong growth numbers), the book is chock-full of useful information.)

> Wealth ownership of that top 0.1% was FLAT from 1948 through 1968

Good point! How to explain that long pause in the long-term trend? I’m gonna ponder that.

>So much for that post-war wealth transfer.

1. The unprecedented long-term trend 29-80 is still staring at us. How to explain the trend, both length and magnitude (and the pause)?

2. Key to understand: the postwar inflation-driven transfer of buying power creditors->debtors is by its very nature not revealed in nominal figures. There are no $ account transfers involved. It’s the buying power that’s “transferred.” So you have to look at Real (relative to a shopping basket of goods), or (similar) relative to GDP.

So just as an example, the massive decline in gov debt/gdp 1945-1980 — from 120% to 35% — reveals we the people watching a huge amount of our collective debt to others (ROW, financial sector) decaying in a huge way. Even while nominal annual deficits continued throughout!

> Are you suggesting that we just spend a shit-ton of borrowed money on defense spending

1. No! There are far more productive investments than military hardware and salaries lying around on the ground waiting to be picked up.

2. For years our gov has been borrowing at negative real rates — being paid to borrow! It’s simply insane not to use that situation to make productive investments that return >er than negative. Then watch that so-called debt get payed off by productivity and production, and decay through inflation, as it did so beneficially for 35 years postwar.

But anyway returning to the topic: is your basic position that we shouldn’t worry our pretty little heads about wealth concentration, because we can count on global financial meltdowns and horrific world wars to manage that for us?

No, I’m saying you shouldn’t worry your pretty little head about it because it’s not a problem in the first place.

The above article criticizes JG because it does not move us towards Keynes’s 15 hour week. The basic purpose of JG is not to enforce or encourage anyone to work any particular number of hours a week. The basic purpose of JG is to provide work for those who want it.

A workfare or “compulsion” element can of course be included in a JG scheme. But that’s an optional extra which some people (doubtless on the political right) would approve of, while others would not.

This is a good work on the subject:

http://kspjournals.org/index.php/JEPE/article/view/1237