Do healthier longevity and better disability benefits explain the long term decline in labor force participation?

by New Deal democrat

Do healthier longevity and better disability benefits explain the long term decline in labor force participation?

A few weeks ago I took another deep dive into the Labor Force Participation Rate. There are a few loose ends I wanted to clean up (at least partially).

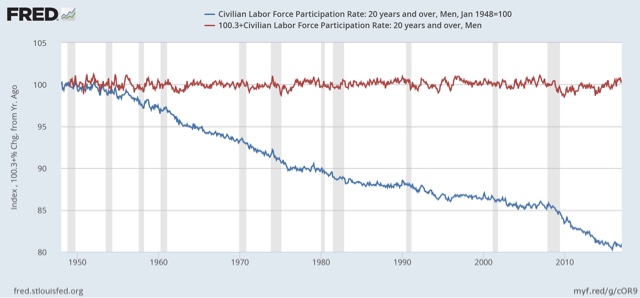

One of the most noteworthy things about the LFPR in the long term is that, for men, it has been declining relentlessly at the rate of -0.3% YoY (+/-0.3%) for over 60 years! Here’s the graph, normed to 100 in 1948, showing the long term decline (blue) and also normed to 100 in 1948, showing the YoY% change +0.3% (red):

Once we add +0.3% to the YoY change, the LFPR always stays very close to 100.

Once we add +0.3% to the YoY change, the LFPR always stays very close to 100.

But what is the *reason* for this very steady decline that has already lasted a lifetime.

I want to lay down a hypothesis for further examination later. I believe the secular decline in the LFPR for men, paradoxically, can be explained by two improvements in disability benefits and health:

1. expansions to the definition of disability; and

2. (a) better health care, leading to (b) an increased life span.

Here’s the thesis: 60 years ago, men (whose life expectancy from age 20 was only to about 67 years old to begin with) went from abled to disabled to dead over a shorter period of time. Now at age 20 they can expect to live to about age 76, and if they get disabled, better health care will keep them alive for a much longer period of time. And more conditions can qualify them for disability. This means that a greater percentage of men qualify for disability, and once on it, they survive beyond working age. (Note that if somebody dies at say age 50 while on disability, they – ahem – are no longer part of the population).

That hypothesis would explain the long term and relentless decline in the LFPR for men.

And there is data in support. To begin with, the life span of males who make it to age 20 has increased by about 1 year over every decade:

And a much higher percentage of former workers are on disability compared with 35 years ago at least:

While applications for disability are sensitive to the business cycle, the percentage of awards (after a decline in the early 1980s) have been rising for 30 years:

Coverage at the St. Louis FRED only starts in 2008, but the current business cycle fits the description (note: not seasonally adjusted):

Following the recession, the number of men on disability who left the labor force declined almost trivially compared with the number of men not on disability who left the labor force. Those on disability bottomed first (2010-11) compared with the able-bodied (2011-12), and surpassed its 2008 level by 2015, whereas able bodied men not in the labor force just pulled even with their 2008 level in 2016.

Obviously more work needs to be done to flesh out this hypothesis, but I think it is a good fit for the data.

cross posted with Bonddad blog

Then teases out why there might be decreased participation, but then we need to dwell on whether this is good or bad. Mr. Douthat (bless his pointy head) would like to make disability more difficult to get, as part of a jobs program that would simultaneously increase the number of jobs and increase participation.

This of course is either mean-spirited or a good thing, depending on whether it would be a good thing psychologically to allow more disabled people to participate in the economy or a bad thing because we would be punishing the afflicted, something they are trying in the UK to much outcry

Makes sense. My immediate follow-up question is whether this holds internationally. Medical interventions impacting health and disability should be broadly similar across the developed world, with some variation for country specific policy.

Using the entire (non-institutional) population over age 20 introduces all kinds of noise in the way of age-based decisions by people and employers. Look just at prime working age adults (25-54) if you want a better idea of the decisions people themselves are making. It doesn’t seem terribly surprising that there would be some gradual decline in the rate of men working as female participation grew so fast. But the decline was not steady. It was basically flat during the 1990s, then started dropping more rapidly as manufacturing employment plummeted in the GW Bush years, and as residential construction disappeared rapidly as the Great Recession came on. Both were male dominated industries. But as much as some would like to believe it’s all good because people are optimizing their happiness, the rapid drop in about seven years after 2000 belies that idea. Culture doesn’t change that fast.

Many things influence LFPR. Longevity and DI are factors.

I think the Black Economy plays a big part. The St Louis Fed put the “informal economy” for OECD countries at 13%. Call that $2Trillion in the US, and no taxes thank you.

Add some of this back into the LFPR chart- what does it look like?

https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/january-2015/underground-economy#table