How do Americans get rich? (and stay rich?)

Originally published at Evonomics and reposted at Naked Capitalism, Angry Bear Steve Roth continues his conversation on riches, income, debt, and expectations. Steve Roth serves as Publisher of Evonomics.

By Steve Roth

How do Americans get rich? (and stay rich?)

It’s the American dream. A third of Americans think they’ll be rich someday. More than half of 18–29 year olds think they will be.

Less than 5% actually make it.* And many of those do it the old-fashioned way: they inherit it. About 60% of U.S. household wealth is inherited. Between a quarter and a third of Forbes 400 billionaires got rich that way. It may not be the most common way to get there, but it’s widespread, and it’s surely the easiest way.

That aspiration to wealth is deeply understandable. Getting high income from a good job is all well and good, but because wealth begets more wealth — people are compensated simply for owning things — wealth is, potentially, forever. It persists, and spreads through families and dynasties. Wealth can, and often does, endure for generations.

So it’s worth asking: how do Americans accumulate wealth? And how does that vary across income and wealth classes? How do the bottom 50% accumulate wealth, for instance, compared to the top 1%?

The Distributional National Accounts

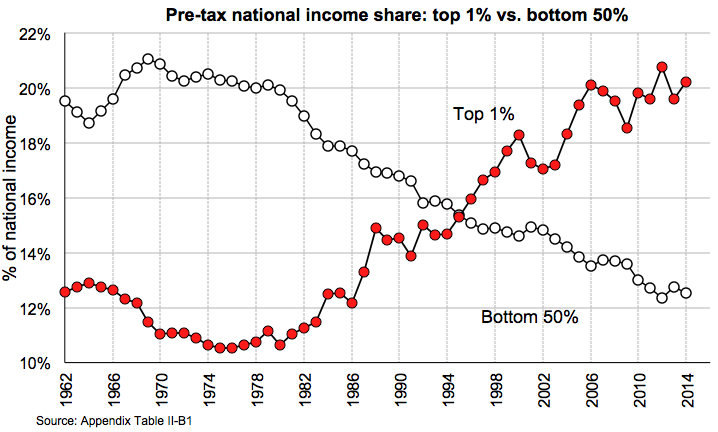

A huge aid to answering that question arrived last month. Gabriel Zucman, Emmanuel Saez, and Thomas Piketty (PSZ) released one of the most important pieces of economic research in the last century. Their Distributional National Accounts (DINAs) reveal the distribution of national income to different income classes, wealth classes, age groups, and genders (and potentially different races, etc. etc.). This has been unavailable in the national accounts, and as a result it’s absent in most macroeconomic empirical work.

Here’s one poster exhibit:

Collect the whole set.

Zucman and company explicitly hope this distributional data “will be adopted by government agencies down the road” (see Conclusion slide). Here’s to it. The DINAs are a magisterial achievement, a treasure trove for empirical economists that merits easy access and prominent, front-and-center presentation in each release of the national accounts.

Income versus Wealth Accrual

But impressive as they are, the DINAs don’t fully answer the question of how Americans accumulate wealth. Because the DINAs only tally income, and income doesn’t include households’ holding (or “capital”) gains on stock portfolios, real estate, etc. Income does include much “property income” — dividends, interest, etc. That’s income from owning things. But it’s not everything that households receive from ownership. Holding gains figure large in that picture.

Any investor will tell you: cap gains are a big part of their wealth accumulation. Total return — dividends plus capital gains — is the measure that most savvy stock-market investors care about, long-term (and that fund managers like to tout, loudly). And much of Americans’ retirement saving — especially middle-class Americans — is accrued through capital gains on their homes.

The DINAs’ central goal is to match income as presented in the national accounts, and to reveal a multidimensional pyramid of distributional data underneath that income measure. A deeply worthy goal. But as a result, the DINAs can’t and don’t reveal the whole picture of household wealth accumulation (change in assets and net worth), or its distribution.

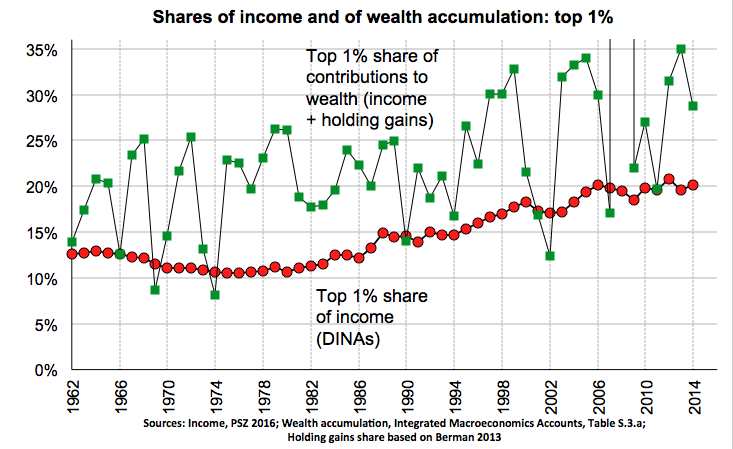

Here’s a rough picture of that disparity, showing a wealth-accrual measure compared to the PSZ income share, for the top one percent:**

Clearly, holding gains are much more volatile that income. But this kind of graph can still tell a long-term, secular story — and even give important insights into shorter-term trends and business cycles.

To get a feel for this: Of $22 trillion in contributions to household wealth in 2013 (income plus holding gains), the top 1% captured $8 trillion, or 35%, compared to 21% of income. That measure has exceeded 30% in eight of the last seventeen years; in the three and a half decades before 1997, it never went above 26%. (2008 is an arithmetic anomaly here, by the way. Household wealth accrual was negative that year, but one-percenters’ wealth accrual, the numerator, was even more negative.)

Concentration of total wealth accrual is almost always far higher, and has been rising faster, than concentration of income alone. The rich are getting richer, faster. It’s an inequality picture more dire even than that depicted in the DINAs. And because wealth begets more wealth, it’s a self-perpetuating picture.

We pay people for doing things, and we pay people for owning things. Increasingly, the latter.

Before expanding and detailing this picture, it’s important to say that Zucman, Piketty, and Saez are deeply aware of this reality — have discussed it many times — even though footnote 10 in their DINA working paper serves rather to obscure than reveal that understanding:

In the long-run, a large fraction of capital gains arises from the fact that corporations retain part of their earning, which leads to share price appreciation. Since retained earnings are part of national income, these capital gains are in effect included in our series on an accrual basis. In the short run, however, most capital gains are pure asset price effects. These short-term capital gains are excluded from national income and from our series.

Gabriel Zucman has given me permission to share his understanding of the issue, sent in private correspondence:

You are correct that there can be pure asset valuation effects in the long run (i.e., capital gains in excess of those mechanically caused by retained earnings). These pure valuation effects are not part of national income, hence not included in our measure of income and our distributional series. However, they could be included down the road by computing income as delta wealth + consumption (i.e., Haig-Simon income). We have wealth in our database so we’re not far from being able to do this.

Such an effort would be very welcome. (Doing so properly would require producing a reconstructed, alternate version of the DINAs calculated based on wealth accrual rather than income, from the ground up — far beyond the rough and ready estimate of one measure provided above.)

That effort would be welcome because: capital gains/losses are not just short-term fluctuations in household wealth, oscillating around some ideal book value determined by income and saving. Wealth accumulation greatly exceeds saving from income, pretty much always and everywhere, over very long periods. And holding gains are not a small part of wealth accumulation, especially for already-wealthy households.

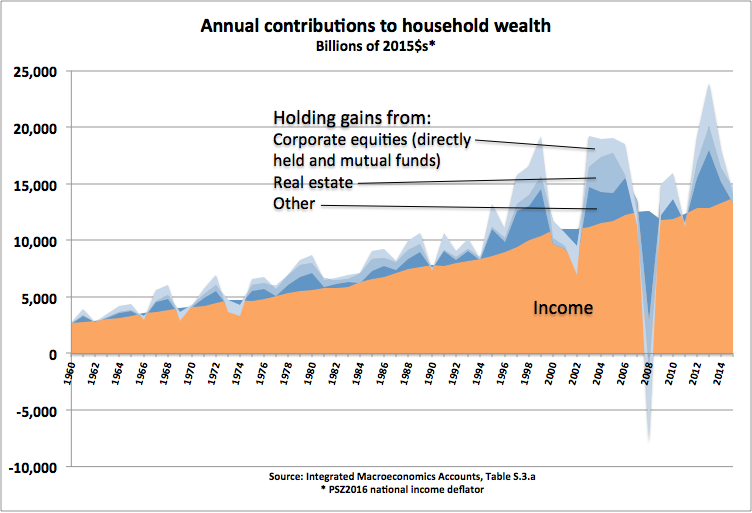

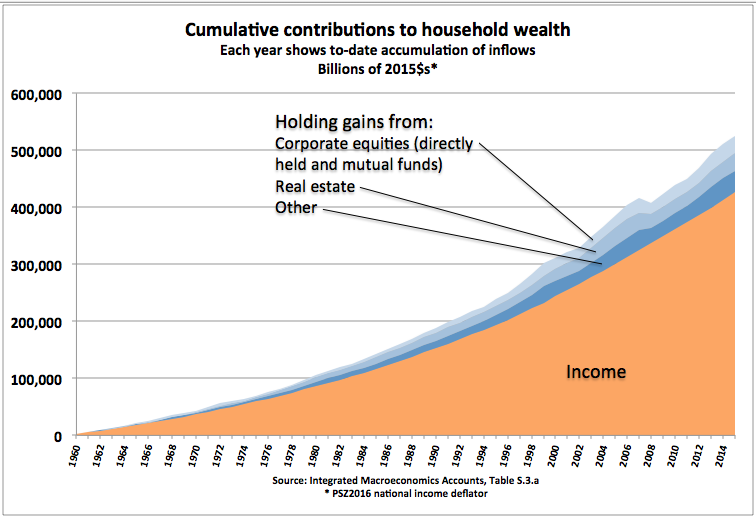

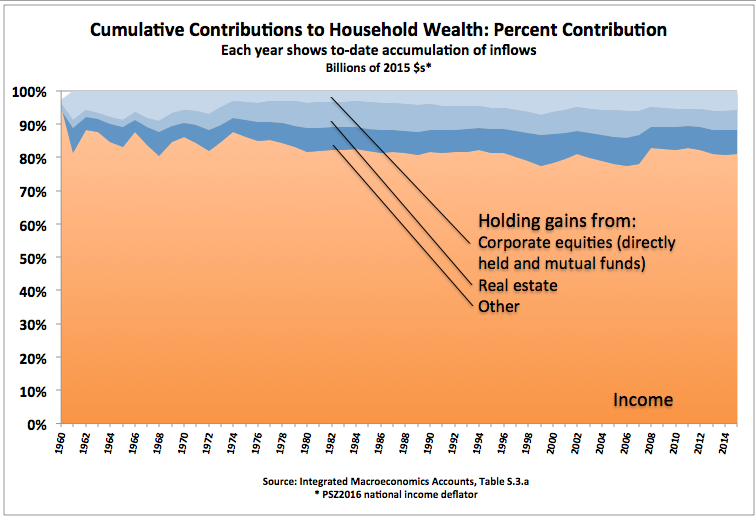

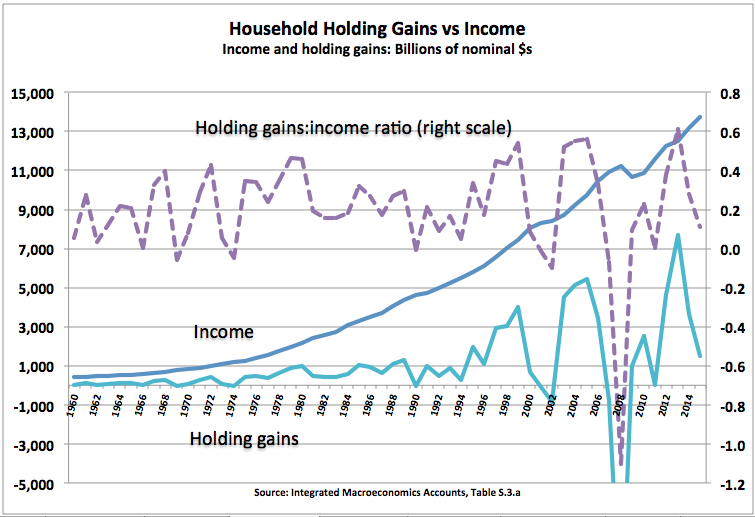

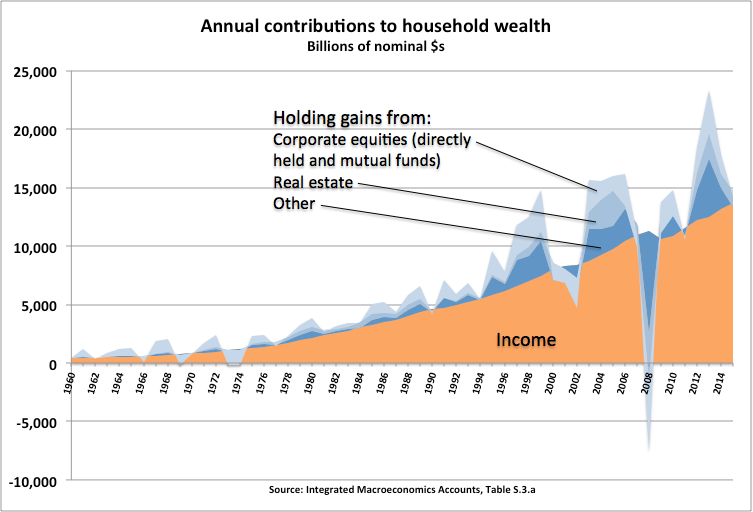

Building the Wealth of a Nation

Below are some more pictures to get a feel for that disparity, based on the Integrated Macroeconomics Accounts (IMAs). They just show contributions to household wealth — additions to the asset side of household balance sheets. They don’t show outflows, deductions from the asset side (the primary one being consumption). Likewise, they only show “market” income — in IMA terms, “balance of primary incomes.” They don’t show nonmarket in- and outflows (mostly government taxes and transfers) that are outside of primary income.*** Holding gains are depicting the IMAs’ accrual-based, mark-to-market accounting for asset values.

2013 is is a recent anomaly here that may surprise people, worth pointing out. Households saw nominal holding gains of $8 trillion that year — equivalent to 60% of income — mostly from gains on equity shares ($3.8 trillion) and real estate ($2.2 trillion).

The share of accumulated, accrued wealth contributions attributable to previous years’ holding gains hit a high of 20% on the eve of The Great Whatever, after creeping up for decades. It dropped precipitously to 15%, and has started slowly climbing since. Absent a far more complete accounting, it’s not clear how that percentage has changed for different income and wealth classes.

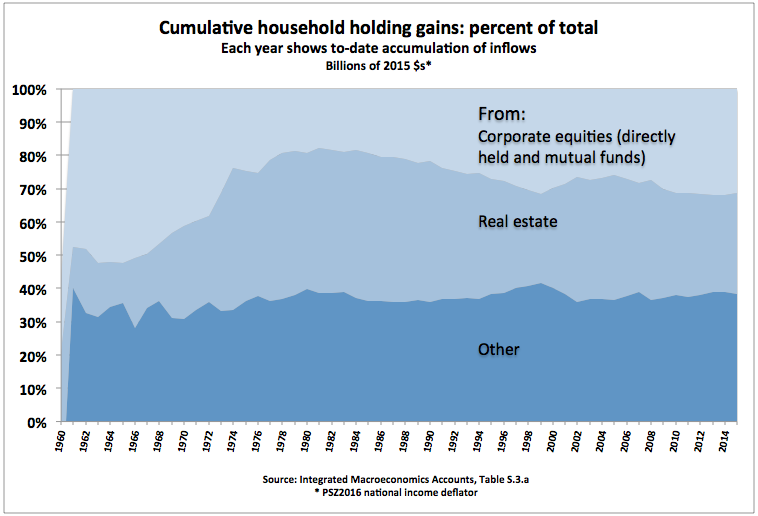

Here’s the previous graph with income removed, zooming in on the proportion of holding gains received from different asset classes:

Holding gains from equities deserve some special discussion, because they’re something of a hybrid:

When firms retain earnings (profits) rather than distributing them to shareholders, the firms’ book value goes up. That increase is the firms’ net saving — think of it as firms saving on behalf of their shareholders. Stock markets certainly consider that increased book value when bidding up shares, so some portion of households’ gains on equities is arguably attributable to firms’ saving. But that portion isn’t delivered as income; households receive it as holding gains. The retained-earnings portion is hidden in those gains.

So is that portion saving from income (by firms), or holding gains (by households)? The answer is yes. It’s a floor wax anda dessert topping.

The key point here is that household holding gains on corporate equities far outstrip corporate saving, and not just over the short term. Over the last several decades those gains have delivered 31 trillion (2015) dollars onto the asset side of household balance sheets — $13 trillion more than corporations saved on households’ behalf.

So What Does it All Mean?

What’s the end result of all this wealth accumulation? I’ll point you to a somewhat outdated picture that puts across today’s massive scale of wealth inequality — far, far exceeding income inequality. Here. Be prepared to scroll.

Looking at all these pictures, you might be tempted to ask: are we just seeing a huge, many-decade, asset-price bubble? (Starting, if the nominal-dollar picture holds any meaning, with the demise of Bretton-Woods in ’71?) It’s possible that this will all revert, rather catastrophically. But I’d suggest otherwise: that we’ve actually been underestimating GDP for decades.

Coming back to our question, how Americans get and stay rich: holding gains are only one way that they get rich. But they may be the primary way that households, families, and dynasties stay rich. Because the wealthier a household is, the more it’s compensated for simply…being wealthy — for owning things, “holding” assets. (Maybe that’s why they call them households.)

That’s the kind of issue that might be well-explored with a DINA-style accounting based on wealth accrual, that includes holding gains. Here’s hoping that messieurs Piketty, Saez, and Zucman think it would be a useful effort.

On that subject, returning to one line of Gabriel Zucman’s:

[Holding gains] could be included down the road by computing income as delta wealth + consumption (i.e., Haig-Simon income).

I’ll just offer one piece of advice based on years proposing and presenting exactly that: think twice about calling it “income” — even with the Haig-Simons tag attached. I’ve received almost-universal pushback on the “comprehensive income” label, even from the most enlightened (and progressive) accounting-based economists, even the proudly heterodox. (Including some at extraordinary length, and occasionally even borderline hysterical in their negativity.) PSZ may have the professional moxie to bruit the label and make it stick. But for whatever reasons — maybe just tradition and convention, but maybe the vested interests of incumbent wealthholders — people are deeply averse to any definition of “income” that includes holding gains.

Instead, call it wealth (or asset, or net worth) accumulation, or accrual, or similar. Those are arguably better labels anyway, easier for most people to understand at a glance.

———————————

* If you were in the top 5% of wealthholders in 2013, you had north of $1.9 million in net worth — not terribly rich, though you could lead a comfortable middle-class life without working (or even better than that, if you don’t have many years left to live and spend).

** This is based on 65% of capital gains going to the top 1% of income recipients — a somewhat conservative estimate according to a 2013 study (Figure 14) based on IRS data, which estimated that measure for 2010 at 85%. This percentage undoubtedly changes over time, but an authoritative time series is not available. It’s also possible, though, that 65% percent is a big overestimate. According to Edward Wolff (in private correspondence), who has studied wealth and asset shares for decades, in 2013 the top 1% of income recipients owned about 24% of household assets. If they only receive 24% of capital gains, in proportion to those holdings (a pretty big assumption), you can stop reading this article entirely; income and wealth accumulation (and change in those measures) are roughly the same. Note that the “% of assets held by” measure seems to be completely unavailable — much less a time series. Professor Wolff was only able to provide that one-year spot estimate for total assets, and PSZ have no such measure — only percent of wealth (net worth).

Bottom line: the distribution of household assets, and especially the distribution of holding gains (relative to the IMAs’ annual mark-to-market revaluation estimates), are in need of further study.

A personal note on that “big assumption” — that households’ capital gains shares are equivalent to their asset shares: I’m an investor in a private, family-held commercial property firm. Actually: in one of the firms’ SPVs or “special-purpose vehicle” LLCs, which owns two other SPV LLCs, each of which owns a middlebrow hotel. The firm quite reliably returns about 8% a year to its investors in income. But over even quite short 5- to 10-year periods, investors’ total returns (including properties’ valuation increases) run more like 16%. All to say: only a minuscule portion of the population has access to returns even vaguely in that ballpark, much less reliable returns at that level. Wondering how Donald Trump got rich(er)?

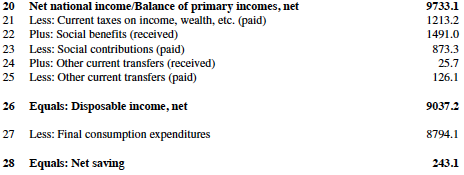

*** The calculation from household income to net saving isn’t just “income minus outflows equals saving”; there are inflows as well.

If that confuses you, join the party. It’s because (primary) income is supposed to represent market income. (And even that is reported after first deducting a significant “use” of household funds: interest payments.) Nonmarket outflows and inflows are jumbled together to derive disposable income, and consumption spending is subtracted from that to yield net saving. You could instead add the nonmarket inflows to market income, then subtract both market and nonmarket outflows, but that’s not how it’s done. Try here to see household sources and uses, inflows and outflows, tallied separately.

2017 January 2

One thing to consider is that value is an emergent phenomenon. We can measure price, but we have to use price to estimate value. The higher you are in the income stream, the less you spend on buying non-wealth goods, so diverting money to the wealthy drives up the prices of wealth defining goods like stocks and real estate. The concentration of wealth is also a self reinforcing phenomenon as that wealth produces income which drives up the price of wealth leading to higher overall wealth and so on.

High marginal tax rates force spending on non-wealth goods. This makes labor more valuable, but it keeps down the price of wealth defining goods, and who would want that.

This is a painstakingly explained analysis of the what, other than climate change, is the seminal issue facing this country and (to a lesser degree, I guess) most of the rest of the world: the staggering spiral of wealth accumulation of a small percentage of families, and the self-propagating mechanisms by which it is occurring.

I’m especially grateful for the discussion of the newly released results of the research by the preeminent wealth- and income-distribution economists of this era (economics and finance aren’t even remotely my area of expertise, and I’m unfamiliar with Zucman, but am familiar with Saez and Piketty), including its limitations and its highlighting of the need for further inquiry into the relation between the METHODS of income and the accumulation of wealth.

And I’m happy to see a counterpoint here to what this blog lately passes off as statistical analysis of wealth- and income- distribution differences between groups of residents in this country and in certain European countries. I’m pretty sure regular readers of this blog will get my drift.

http://angrybearblog.strategydemo.com/2017/01/i-still-think-thomas-is-a-hack.html

http://angrybearblog.strategydemo.com/2017/01/culture-matters-oil-curse-edition.html

Good grace. Reading this article was a whiplash experience.

And: Bernie Sanders forever!

Bev,

And this concentration has allowed the Kochs and the Popes of the world(Pope has enough for North Carolina) to dominate state elections.

People keep talking about the failure of the Dem Party in state and House elections, while that is a true story it ignores that the DP does not have the resources to compete in those areas.

True, they do have the cash for Presidential elections, but not at the state level where, since Citizen’s United, the cash has turned the states into GOP playgrounds.

Look, I am a Bernie guy(though often accused of not being one), but Bernie’s biggest fault is that he did not learn to add until he was 70 years old.

“Bernie Forever” sounds great, but it ignores the simple fact that US politics is an us or them game. And that any division of one side takes a hard task and makes it impossible.

Bernie has woken up, we need all Bernie fans to do so. Though I doubt that the sanrandonistas ever will. Just as I know they have been asleep their entire lives.

Well, let’s go with “top 5%” as being “rich”.

While that’s just shy of $2M overall, for the 60-64 cohort (retirement age — where folks have pretty much gotten where they are going to get), that bar is up to $3M.

At the other end, someone aged 30-34 with a mere $400k is in the top 5% for that age bracket.

The main reason that capital gains are not considered with other income is that you cannot do anything with it until you sell. To realize the gains, you have to sell the asset that had the gains. Who’s going to buy it? Someone with other income, which has already been counted. If you count it as income when HE got it, AND when he gave it to the person from whom he bought the asset. But that transfer created nothing — no new goods were created, no services performed.

To say that the Democrats don’t have the money is just silly. There are a gazillion Hollywood millionaires. There is Bloomberg. There is Soros. There is Secretary Kerry. The Clintons are millionaires. The Obamas are millionaires. They have Warren Buffet. They have Bill Gates.

BTW, Picketty and company have done a fantastic job with the data collection, and I highly recommend Capital in the Twenty-First Century. His thesis uses the wrong growth rate for comparison, but the data make it worth the read anyway.

‘Because the wealthier a household is, the more it’s compensated for simply…being wealthy — for owning things, “holding” assets.’

Depends on the “assets.” Robert Kiyosaki uses that definition of “asset,” but many do not. It is common to consider cars as assets. But except in rare instances (such as Uber and pizza delivery), they do not provide positive cash flow, but negative cash flow. As such, they should be considered liabilities. Having that liability can reduce other negative cash flows, such as calling Uber yourself or getting delivery instead of DiGiorno. People also consider gold an asset. But owning gold does not produce positive cash flow. You have to have somewhere to store it — a safe or a safety deposit box. You might want to insure it, too, if you store it at home. Even one’s home is a liability. Even without a mortgage, one has repairs, maintenance, and taxes to pay. Smaller house, smaller liability. And if the factory in your factory town moves to Mexico, who will buy that house? So one has to weigh those liabilities against those that one would incur without a house — rent.

Wealth is accumulated by purchasing those things which produce a positive cash flow, and by minimizing purchasing things the provide a negative cash flow.

Warren,

I hope fervently you have no children. That is for the good of the species.

If you do have children, I hope they never read your thoughts in that post.

I mean, seriously, what the f@@@ do you do when you are not posting gibberish on the internet?

I also recommend The Millionaire Next Door for this topic.

I have not read the latest version, but in the former, the most common vehicle owned by millionaires was an F-150. They lived in the first house they bought, and were still married to their first spouse.

Granted, this is not the $3M level one needs to be in the top 5% of the 60+ cohort, but it’s a start.

I don’t worry too much about families staying wealthy: “70% of wealthy families lose their wealth by the second generation, and a stunning 90% by the third, according to the Williams Group wealth consultancy.”

http://time.com/money/3925308/rich-families-lose-wealth/

Pardon the typo. That should have read, “I don’t worry about families’ staying wealthy.”

So, if I am sitting on a billion dollars worth of gold, I am not wealthy because it is not producing a positive cash flow?

Let’s look at it this way, Jerry…

You spent a billion dollars to buy that gold. It is now paying no dividends, and no interest. AND you have to pay to store that gold, and you may want to buy insurance on it. MAYBE it will be worth more in the future, and maybe not. In the meantime, it is costing you money to own.

That does not seem like a good way to BUILD wealth. As the original post puts it, you are not “[being] compensated simply for owning [it].”

Investment in gold is useful only as a hedge position to balance bond ownership. (I think the recommended ratio 1:10 gold to bonds, but I don’t remember, since I have so little in bonds it’s not worth the trouble.) My only gold ownership is a couple pieces in my coin collection, which I do not consider and investment, but a hobby.

Warren I don’t have time to go through this in detail but this is just not only simplistic but straight out wrong:

“The main reason that capital gains are not considered with other income is that you cannot do anything with it until you sell.”

Are you saying homeowners cannot borrow against equity (they call these ‘mortgages’) or use the accumulated value of their savings, investment funds, 401-k’s to establish and use consumer credit?

To take it to business perhaps you are unaware that Apple and other comanies can use off shore assets as collateral to sell corporate bonds to full stock buy backs that increase the capital of existing stockholders in ways that allow major stockholders like Carl Icahn to fund both a lavish lifestyle and more corporate acquisitions?

To put up such a sentence responsding to a post by Steve of all persons is to reinforce something I e-mailed to the blog runners this morning: “Warren is punching above his weight”.

There is a phenonenum I identified back in my first years in grad school, oddly having heard someone early in ther term “explaining” the magic of markets as “proved” by the first chapter of his Economics Principles text. I call it “The Smartest Sophomore on the Dorm Floor”. Because there is nothing so inane that you can’t convince a sub-set of entering Freshman. On the other hand your first day in a graduate seminar will disabuse you of that notion.

If I have a billion dollars in gold I have nearly a billion in useable credit.

Christ until 1932 stocks of gold were though necessary for nations to have a “sound currency”. And even now our currency are called “bills” and labeled “notes”, that is credit instruments.

Mark Twain wrote a story on this theme called the “Million Pound Bank Note” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Million_Pound_Bank_Note

Among many other works inspired by it it gave the plot premise for Trading Places.

Credit deployed correctly is wealth, just as unwise deployment of credit can lead to bankruptcy. And capital and even more capital gains gives you credit.

“Are you saying homeowners cannot borrow against equity (they call these ‘mortgages’) or use the accumulated value of their savings, investment funds, 401-k’s to establish and use consumer credit?”

Actually, they CANNOT use 401(k) money as collateral.

As for the others, no, I am not saying that at all. However, but taking out a loan is a liability. To pay off the debt, one must have income, or one must sell off some of the assets. Either way, the capital gains on those assets are not income.

Now, as for “punching above [my] weight,” I will plead guilty on the following basis:

From the original post: “I’ve received almost-universal pushback on the “comprehensive income” label, even from the most enlightened (and progressive) accounting-based economists, even the proudly heterodox. (Including some at extraordinary length, and occasionally even borderline hysterical in their negativity.) PSZ may have the professional moxie to bruit the label and make it stick. But for whatever reasons — maybe just tradition and convention, but maybe the vested interests of incumbent wealthholders — people are deeply averse to any definition of “income” that includes holding gains.”

If such as they cannot get through to him, I don’t stand a chance.

In my area of SoCal, many people my age became rich on paper simply by holding property especially rental property. They may not make the statistics because they do not sell but they are very, very well off nonetheless. Let me give you an example. I bought a condo in 86 in Santa Barbara for 125 grand. That condo is now worth 600 grand. Had I kept it, it would be paid off and I could rent it out for 2-3 grand a month. Many of my friends that help such properties leveraged them over the years to buy more properties. The college town of Isla Vista is filled to the brim with students paying landlords upwards of 4 to 7 grand a month for an apartment I used to rent in 75 for 200 bucks a month.

Woolley:

Mike lives in California. I am sure he has a handle on your point also.

If you inherited 3 million or more dollars, there is a 90% chance that none of it will be left for your grandchildren.

The big problem with the article is that its title implies it will discuss inheritance as the driving factor in becoming wealthy, but it instead deals with wealth inequality. It is an important, but separate issue, one that is not contingent upon wealth passed down from one generation to the next.

Foreign born and first generation Americans are, statistically speaking, disproportionately wealthy. Hard to explain that if the ‘blue-blood’ framework’ were actually true.