Why the Rich Hate Inflation: Because They’re Creditors?

Paul Krugman and assorted others have been puzzling at this question recently, one that I’ve been grinding an axe about for some years. For the first time, I think, Krugman’s highlighted the explanation that I keep going on about:

Inflation helps debtors and hurts creditors, deflation does the reverse. And the wealthy are much more likely than workers and the poor to be creditors, to have money in the bank and bonds in their portfolio rather than mortgages and credit-card balances outstanding.

Higher inflation means debtors pay off their loans in less-valuable dollars. So given an outstanding stock of trillions of dollars in fixed-interest loans/bonds, an extra point of inflation should transfer tens of or hundreds of billions of dollars a year in real buying power from creditors to debtors (without a single account transfer happening). Instantly and permanently.

I got some judicious pushback on this thinking in comments from JKH over at Interfluidity, where I had emphasized that rich households own the banks. (The top 20% actual own more like 85% of corporate equity.) While the 20% certainly have debts, they owe them mostly to themselves as bank shareholders, so The-20%-As-Debtors don’t benefit from the cheaper payback caused by inflation; it’s a wash. The 80% do get that benefit (and the 20% suffer), because the 80% owes money, on net, to the 20%.

I tried to simplify the situation with this:

Isolating one component that bank shareholders can be sure of, in a sea of complex and uncertain effects.

Imagine a bank (owned by shareholders, all in the top 20%) that owns a bunch of 30-year fixed-rate loans (borrowed by 80%ers) that won’t expire for 15 years. No ongoing lending by the bank. It just holds these loans and collects interest.

All interest is paid at the end of the year.

The banks’ interest revenues on those loans this year were $1 billion. Expenses were $100 million. $900 million in profit, all distributed as dividends.

Inflation over the next year (and ensuing) is 1%/year.

The bank again makes $900 million in profits, and distributes it to shareholders.

But the 80%er borrowers only pay $891 million in real buying power, and the 20%er shareholders only receive $891 million.

The next year, $882 million in buying power. Etc.

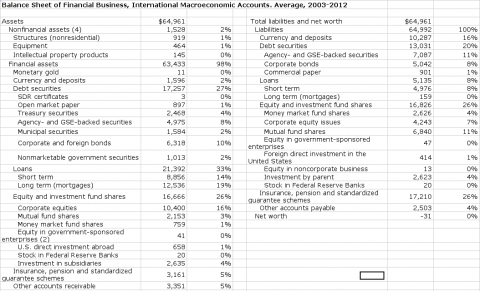

JKH pointed out out again that this only addresses inflation’s effect on the banks’ assets, not their liabilities. Very good point. Here’s an effort to address it, starting with the Balance Sheet account for Financial Business in the International Macroeconomic Accounts. (I averaged the balance sheets for 2003-2012 to get a big overall picture.) Click for larger image.

Now to ask: from the perspective of the 20%er shareholders/bank-owners, what effect will inflation have on these various assets and liabilities?

In many cases it’s quite uncertain (the whole point of the Interfluidity post linked above). They may presume that “Equities and investment fund shares” will go up along with inflation, for instance, so that’ll be a wash. What about “Insurance, pension, and standardized guaranteed schemes”? (I love “schemes” here.) Inflation should help them there, perhaps a lot, but how much and how will those schemes transform over future years and decades? Again, pretty uncertain.

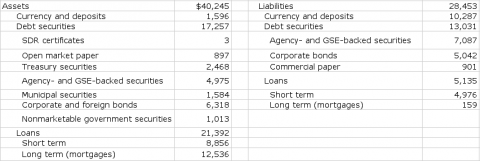

But debt and debt securities are predictable, at least to the extent that they’re fixed-rate loans. Inflation hurts creditors. Period. Let’s just look at those assets and liabilities (click for larger):

Not all of these are fixed-rate, but we can assume that most of them are. (Estimates welcome.)

Here, banks’/20%ers’ assets (what others owe them) exceed their liabilities (what they owe others) by 12 trillion dollars. They’re net creditors. No duh.

To the extent that this stock of outstanding obligations is fixed-rate, an extra point of inflation will decrease 20%ers’ buying power by $120 billion a year.

Now you may suggest that that’s actually small change. It’s roughly 3% of the 20%ers annual income from capital,* and only $6,000 a year for each of the 20 million households in the top 20%. But you can be quite sure that that number is at least one order of magnitude larger for households in the top 1, .1, or .01%.

If the top 1,000 or 10,000 households (who dominate policy) perceive themselves as losing, say, $600,000 a year in real buying power for each point of inflation, are you curious why they hate inflation?

* Rough calculation of 20%ers’ capital income: (National income of $15 trillion – 60% of income going to labor) * Top 20’s 85% share of capital ownership = $5.1 trillion

Cross-posted at Asymptosis.

I think your analysis is a little over-simplified.

If inflation is 3%, then interest rates will reflect that. If inflation is 13%, then interest rates will be commensurately higher.

What the rich do not want is for the inflation rate to increase. If inflation increases 1% (say from 3% to 4%), then your analysis would be correct, because the loans assumed 3%.

This is why they invented variable-rate mortgages. Credit cards are invariably 🙂 variable-rate, as are HELOC’s.

Personally, I think credit cards are one of the most evil inventions ever. The Empire would be proud:

Rats — embedded frame didn’t work:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q4bd3O4SVIY

I would add that the rich hate inflation because they are employers, and don’t want to have to raise wages for workers.

I recall that, throughout the 1990s, conservatives worried about “wage push inflation”. Of course it didn’t happen. While productivity grew,

employers shared only a tiny bit of the growth with workers.

Even when I was a child, I recall the classic debate between

Republicans and Democrats: Republicans feared inflation, because it eroded their wealth. Democrats feared unemployment.

Republicans, of course, claimed that without a certain amount of

unemployment, workers would be able to demand higher pay.

A very significant portion of fixed rate debt is held by A) foreign central banks and the B) Federal Reserve, C) Social Security is the biggest fixed rate investor in the world (Total Inter-governmental debt is now about $5T). Another chunk is from D) bond funds. Who are the investors in bond funds who get smacked if inflation were to double? E) Small Investors!

So when you allocate the loss of high inflation to the fixed rate ‘savors’, who on that list would you like to see take the hit?

Actually this goes back a long time. Shay’s rebellion was about the unwillingness of MA to inflate and the resulting inability of the debtors to pay. Another example from about the same time. Rhode Island had inflated its currency, and did not ratify the 1787 constitution until Washington told them to ratify or face tarriffs, because at that time the debtors held power and felt that the 1787 constitution would benefit the creditors. Also in some sense inflation versus sound money was the main subject of the 1896 election where Bryan was in favor of inflation.

And we also have the retirees, who tend to be heavy in bonds relative to equity. Low inflation means low bond income for them.

Jack,

AH

Exactly how many retirees live in the US who give a rat’s ass about low bond income?