The Fed is not “Printing Money.” It’s Retiring Bonds and Issuing Reserves.

Mark Dow had a great post the other day:

There is zero correlation between the Fed printing and the money supply. Deal with it.

He points out (emphasis mine):

From 1981 to 2006 total credit assets held by US financial institutions grew by $32.3 trillion (744%). How much do you think bank reserves at the Federal Reserve grew by over that same period? They fell by $6.5 billion.

As he says:

if you are an investor, trader or economist, understanding—and I mean really understanding, not just recycling things you overheard on a trading desk or recall from econ 101—the mechanics of monetary policy should be at the top of your checklist. With the US, Japan, the UK and maybe soon Europe all with their pedals to the monetary metal, more hinges on understanding this now than ever before.

And, as we saw this week, even many of the Titans of finance and economics have it wrong.

He’s obviously been reading Manmohan Singh and Peter Stella (S&S) over at Vox EU, who cite the very same numbers and add:

In fact, total commercial bank reserves at the Federal Reserve amounted to only $18.7 billion in 2006, less than the corresponding amount, in nominal terms, held by banks in 1951.

S&S also point out (Table 1 and Figure 1) what we’ve known for decades but many seem unwilling to admit: since WWII, reserve levels have had approximately zero correlation with inflation/price levels.

They continue:

This suggests either that there is something wrong with:

- the theory of money neutrality;

- the theory of the money multiplier; or

- how money is measured.

Or, I would say, all of the above. I’d actually replace all three: there is something wrong with the (nonexistent) definition of “money.” But that’s another post.

I’m going to go even farther than Dow and say: the Fed is not printing money. (It can do that, but the result is stuff you can hold in your hand.) That’s a confusing and actually incoherent misconception. The Fed is issuing new reserves and exchanging them for bonds. Those bonds are effectively retired from the stock of assets circulating in the financial system (though perhaps only temporarily), as if they’d expired.

Reserves are not “money” in any useful sense. Or, they’re only money (whatever you mean by that word) within the Federal Reserve system. We probably just shouldn’t use the word at all here. It’s only confusing.

The key to understanding (and to avoid misunderstanding) this is to think about the banking system, not individual banks. The dynamics are totally different, because individual banks can affect their reserve positions (though under various market and regulatory constraints). The banking system can’t.

Because: Reserves only exist (can only exist) in banks’ accounts at the Federal Reserve Banks (and only members — banks plus GSEs and other large institutions like the IMF — can have accounts there). The banking system can’t remove reserves from the system by transferring them to the nonbank sector in exchange for bonds, drill presses, or toothpaste futures.

One bank can transfer reserves to the account of another entity with a Fed account, in exchange for bonds or whatever, but total reserves are (obviously) unchanged. And that exchange has no direct effect outside the Fed system. (That exchange can, does, have second-order, indirect, portfolio-rebalancing effects on the rest of the market. More below.)

And here’s the key thing: the banking system can’t lend reserves to nonbank customers by somehow transferring them to those customers’ deposit accounts (thereby reducing total reserves). They can’t “lend down” total reserves. The banking system doesn’t “take money” out of total reserves, or reduce those reserves, to fund loans.

This is why it’s so crazy to worry about those reserves eventually “flooding out into the real sector” in the form of new loans (and resultant spending), with all the hyperinflationary hysteria attached to that notion. (Equally: those reserves are not “unused cash” on the “sidelines” that the banks are “sitting on.” See Cullen Roche on this.) Reserves can’t leave the system, whether in a flood or a trickle. The banking system will lend (creating new deposits in its customers’ accounts out of thin air), if bankers think it will be profitable. But increased lending if anything forces the Fed to increase total reserves. Viz:

A bank issues a billion dollars in new loans, creating a billion dollars in deposits in its customers’ accounts. The borrowers spend the money by transferring it to sellers’ banks. When all the transactions net out at night at the Fed, the issuing bank is short on reserves that need to be transferred to the sellers’ banks (or sees that it will be short). So it borrows reserves from other banks. If reserves are tight, this pushes up the interbank lending rate. The Fed doesn’t want the interbank rate to increase, because it thinks interest rates are where they should be to fulfill its mandates. So it issues new reserves and trades them for banks’ bonds (which it retires, at least for the time being).

Short story: more lending increases total reserves. Slightly longer story: more lending forces the Fed to increase total reserves (or abandon its mandates).

In the current situation, of course, there’s no shortage of reserves. Banks are holding extraordinary quantities in excess of regulatory requirements. So the Fed instead controls the interbank lending rate within a corridor by setting the rate it pays on reserves (bottom) and the rate at which it will lend to banks (top). Read it all here from the FRBNY.

So how can the banking system reduce total reserves? Only in one significant way: by buying bonds from the Fed. Send some reserves over, and the Fed retires those, (re)issuing bonds in exchange. But of course the Fed isn’t selling these days; it’s buying.

Fed asset moves just issue and retire reserves and bonds. And those moves are purely at the discretion of the Fed (the Fed “enforces” this on the system by buying/selling at prices that individual banks will take up). So the Fed is in complete control of the level of total reserves. Again: there is no way for the banking system to turn existing reserves into deposits in its customers’ accounts. It can’t “lend down” total reserves.

When the Fed issues and retires bonds and reserves, it’s not “printing money,” so it’s not playing some kind of simplistic MV=PY game. It’s adjusting the balance of the banking system’s portfolio (“forcing” it to change exchange bonds for reserves) — and by extension, affecting the mutually interacting portfolio preferences of all market players (via interest-rate/yield-curve effects, and also, more psychologically, by imparting the optimistic notion that there’s adult supervision — that this frat party won’t turn into Animal House).

In other words, it’s a much deeper game than many monetarists would have you believe. It’s especially deep because neither the Fed nor the markets understand it properly. Certainly the Fed governors have strong disagreements about how it works. (Arguably, nobody understands, very much including me. There are many interacting understandings and reaction functions out there, many based on complete misunderstandings of the system dynamics. But I think we’re getting closer these days, with the slow but increasingly widespread and accelerating dismissal of silly notions like the money multiplier.)

Dow explains these portfolio effects and reaction functions very nicely:

…why is the Fed doing QE in the first place?

By keeping rates low well out the yield curve and providing comfort that the Fed will be there to fight the risk of recession and deflation…we start feeling better about putting our getting our money back out of the mattress and putting it back to work.

…it is the indirect psychological effects from Fed support and the low cost of capital—not the popularly imagined injection of Fed liquidity into stock markets—that have gotten investors to mobilize their idle cash from money market accounts, increase margin, and take financial risk. It is our money, not the Fed’s, that’s driving this rally. Ironically, if we all understood monetary policy better, the Fed’s policies would be working far less well. Thank God for small favors.

…

The other, more mechanical, implication is that financial sector lending is neither nourished nor constrained by base money growth. … The main determinant of credit growth, therefore, really just boils down to risk appetite: whether banks and shadow banks want to lend and whether others want to borrow. Do they feel secure in their wealth and their jobs? Do they see others around them making money? Do they see other banks gaining market share?

These questions drive money growth more than the interest rate and base money. And the fact that it is less about the price of money and more about the mental state of borrowers and lenders is something many people have a hard time wrapping their heads around—in large part because of what Econ 101 misguidedly taught us about the primacy of price, incentives and rational behavior.

I certainly make no claim to a deep understanding of those portfolio effects. (If I had such an understanding, I’d be far richer than I am.) But I do have some thoughts I’d like to share.

• When the Fed issues reserves and retires bonds, it’s 1. reducing the net flow of newly-issued (treasury and GSE-mortgage) bonds into the market, or even causing a net reduction. And if the latter is true, it’s 2. reducing the total stock of bonds available for trading in the market.

Since the flow of new bonds is obviously much smaller than the outstanding stock, you would expect flow effects of Fed actions to have much greater immediate influence on bond markets than stock effects.But it’s unclear what their long-term effects might be. A steady flow reduction, on the other hand, will eventually have cumulative effects on the total stock — again with uncertain future effects.

Jake Tepper, quoted in this post by Cullen Roche (read the comments too), gives us this:

…The fed is going to purchase $85 billion of treasuries and mortgages a month. So over 500 billion in six months…. the net issuance [by Treasury] versus refunding is a little over 100. That means we have 400 billion, 400 billion that has to be made up.

Whatever “made up” means. But Tepper’s also ignoring the Fed’s other big buys: mortgage-backed securities issued by government-sponsored enterprises (Fannie, Freddie). I would like to see as long a time series as possible of the following:

Net MBS issuance by GSEs (issuance – retirement)

Plus:

Net Treasury issuance (new issues – retirement)

Minus:

Net Fed ”retirement”

Also have to include Fed repos, I think? But maybe trivial over the long term.

In other words: net Net NET consolidated flow of new bond issuance to the private sector by Treasury, Fed, and the GSE gods.

Then: that measure as a percent of GDP? Of total Treasury/GSE bonds outstanding? Total Credit Market Debt Outstanding (TCMDO)? Other measures to compare it to?

• Contrary to what you often hear, even today when reserves and bonds are paying nearly equivalent interest rates, they are not equivalent assets. Because: bonds have expiration dates, and variable market prices/interest rates. So bonds carry market/interest-rate risk and reward for their holders — the potential for cap gains and losses. Reserves don’t.

As you can read in this must-read 2009 paper from the Bank of International Settlements, reserves are the Final Settlement Medium. They’re what it comes down to every night when all the day’s bank transactions are consolidated, netted out, transferred, and resolved. A dollar of reserves is always worth a dollar. There’s no possibility of capital gains or losses on reserve holdings. Reserves are inexorably nominal. (Even more so than $100 bills, which are worth less relative to reserves if they’re sitting in a Columbian drug-dealer’s suitcase.)

So when the Fed gives the banks reserves and retires bonds, it’s taking on market risk/reward, replacing it with absolutely nonvolatile, risk/reward-free assets (at least in nominal terms). It’s removing leverage and volatility from the banking system. (MMTers might well ask why our government system requires the injection of that volatility in the first place, when the Treasury could simply be issuing “dollar bills” with no expiration dates or interest payments, instead of treasury bills. [Or consols.] But that’s an aside.)

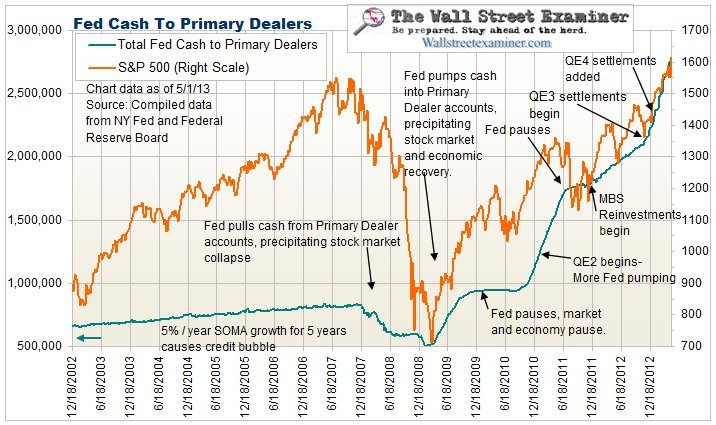

• I have to address notions like this one from Lee Adler, in a comment on Dow’s post:

The correlation between Fed and other central bank money printing with market behavior is clear and direct.

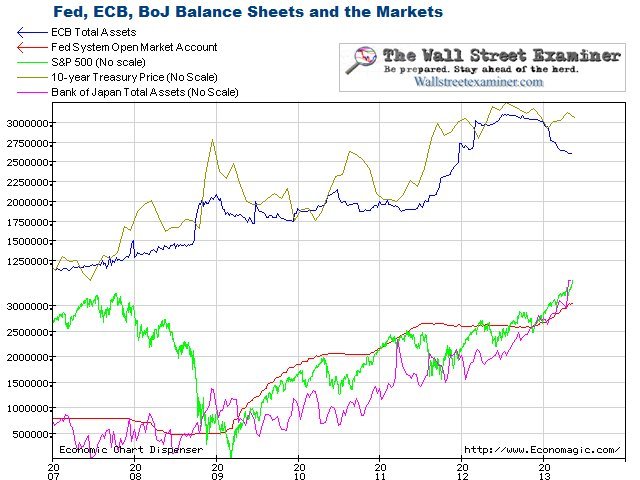

Yeah: while the Fed is on a bond-buying spree, it buoys bond prices and depresses yields. Especially when bond yields are historically low, market players shift their portfolio preferences from bonds to equities in a “reach for yield,” so equities go up too. (This presumably yields a wealth effect of [rich] people spending more — perhaps the only transmission mechanism to the real economy for Fed balance-sheet changes.)

This says exactly nothing about those balance-sheet moves as an impact on the stock of “money,” or inflation. It just says that while Fed asset purchases/sales are ongoing (and expected to continue), they will raise or lower the value of financial assets. It’s either orthagonal to Dow’s assertions, or in fact demonstrates exactly what he’s saying about psychological effects.

• It doesn’t make sense to say that the Fed is “monetizing” the debt (because reserves aren’t money). If you think in terms of consolidated Treasury/Fed net issuance/retirement of government bonds, it’s retiring debt — removing bonds from the market and absorbing them into the Treasury/Fed complex. The bonds still exist, of course, and the Treasury still pays interest — to the Fed, which kicks it right back to Treasury. But as far as the markets are concerned, those bonds are essentially dead and gone (at least for now).

It seems that the Fed could simply burn a whole pile of those bonds, no? It would have no effect on flows, aside from the rather pointless interest flows back and forth between Treasury and Fed. And it would only affect the stock of “dead” bonds — ones that have been retired into the Fed. (The notion’s been discussed by people as diverse as Ron Paul and Mervyn King — Paul with the misconception that this would be “declaring bankrupcy,” and King with the misapprehension that it would be “monetizing the debt.”)

• It’s not at all clear what the flow effect would once the had Fed stopped net-buying bonds, while Treasury and the GSEs continued issuing new bonds in excess of retirements. Financial asset prices might stay at their then current levels. Who knows.

• The question, of course, is whether the Fed will ever sell all those bonds back to the market (thereby reducing reserve holdings). The average maturity of the Fed’s bond holdings is >10 years, so they’ll naturally expire and disappear, but only slowly. We’ve entered a brave new monetary world, in which central banks exert themselves not just through reserve management/interbank lending rates, but through balance-sheet expansion and contraction. (See the two “schemes” in the BIS paper linked above.) I don’t know if anyone knows what to expect in that regard. The Fed’s certainly talking about reducing its bond purchases in the future, which will affect net bond flows into/from the market, but it’s not at all clear whether it will ever shrink its balance sheet to pre-crisis levels (in absolute terms or relative to other measures), thereby reducing banks’ reserve holdings to those earlier levels.

• The $10-trillion question: If the Fed did sell off all its bond holdings in an effort to get back those halcyon days when banks didn’t hold any excess reserves — so the Fed could control the interbank rate with small open-market operations — what in the hell would happen? Whether slowly or quickly, bond prices would fall as the sales continued, yields would rise (compared to a counterfactual in which the Fed wasn’t selling off their holdings). Markets would shift their portfolio preferences from stocks to bonds, so equity prices would fall along with bond prices. Disastre?

Again, I don’t think anybody knows.

Cross-posted at Asymptosis.

Awesome post!… I would like to highlight one part…

“but it’s not at all clear whether it will ever shrink its balance sheet to pre-crisis levels (in absolute terms or relative to other measures), thereby reducing banks’ reserve holdings to those earlier levels.”

It may be that the sheer size of the derivatives market requires the reserve level to be permanent, as a stop gap for any one bank.

@Edward: “It may be that the sheer size of the derivatives market requires the reserve level to be permanent, as a stop gap for any one bank.”

Very interesting notion. Ties in to my notion that they’re effectively removing leverage and volatility from the financial markets by substituting absolutely nonvolatile reserves for market-risky bonds.

It doesn’t have to remove the excess reserves by reversing its purchases. It can let future deficit spending (Treasury issuances) soak up the excess reserves over time. In the mean time it can manage its target interest rate my making changes to its interest rate it pays on excess reserves.

Below are some of Paul Volcker’s comments from a March 13, 2013 economic conference sponsored by the Atlantic magazine:

“Obviously, the Federal Reserve has come to play an extraordinary role in maintaining the economic recovery. In doing so, it stepped out of the long-established but more limited institutional role of a central bank. Instead of confining its operations to intervention in the money markets and control of bank reserves, attention is today directed toward massive support directly and indirectly of capital markets – and most particularly the market for residential mortgages. What it amounts to is that the Fed has become the principal intermediator in American financial markets. It’s acquiring several Trillion dollars of securities of varying maturities on the basis of short-term monetary liabilities that it itself has created. In the common vernacular, that is termed ‘printing money.’

http://www.prudentbear.com/2013/03/insight-from-former-fed-chairmen.html

Volcker: In the common vernacular, that is termed ‘printing money.’

@Anon: “In the common vernacular, that is termed ‘printing money.’”

Right. Exactly my point. I’m here to suggest that 1. that common vernacular is misbegotten and confused, and 2. its widespread usage results in ubiquitous misunderstandings of how the financia/monetary/economic system works.

And: it results in *particular* misunderstandings that are pernicious.

Two points:

1) An analysis that only has data up to 2006 is pretty worthless in figuring out what the Fed is doing in 2009020013.

2) Believing that CPI is a proxy for the Fed printing money ignores basic economics:

MV = PQ

Changes in M can be offset by changes in P as measured by CPI, but they can also be offset by changes in V or Q. Please look at: http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?id=M2V, to understand that M2 velocity has dropped from over 2.1 to just over 1.5 since the mid 1990’s. This nearly 33% decline would have downward pressure on price/inflationary measurements such as CPI.

I did not have printing with that money!

I did not have precedent with that Cyprus forfeiture!

I did not have Pinocchio with that nose!

I did not have walk or quack with that duck!

I did not have impoverishment with those retiree savers,

pension funds, endowments!

The issue is gravitas (Volcker) vs. up up and away in my beautiful my

beautiful…

Conjuration enabling circular state finance is, if history serves guide,

the end game.

@Josh: “1) An analysis that only has data up to 2006 is pretty worthless in figuring out what the Fed is doing in 2009020013.”

True, but that series makes its point quite tellingly. But see below.

“MV = PQ”

Just whaddaya mean by M, buster? 😉 That’s rather the whole point here.

*None* of the monetary measures M0-MZM include Fed reserves. By those definitions, Fed reserves are not money, so when it issues new reserves it is not printing money.

Fed reserves are included in only one monetary measure, the Monetary Base or “base money.”

This measure, by monetarist standards and thinking, has become extremely…problematic since the early 80s:

Steve,

Using an M you want, AMBNS (I prefer non-seasonally adjusted measures as they are less open to bias manipulation) there still is the same issue. ABMNS has seen significant year over year increases since 2008, maxing out at 30% in 2009 all while every velocity measurement has has been year over year mainly negative during that time.

The point is that more money does not equal higher CPI in all cases. Velocity matters and has been dropping for a while. Without increases in M, the decreases in V would have led to lower P.

@Josh: “Using an M you want”

Well there’s only one M that includes Fed reserves, and that’s what we’re talking about here…

Are you telling me that velocity is 1/18th what it was in 1980?

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fredgraph.png?g=itx

I think it’s pretty clear that increasing national share of income and wealth apportioned to the top 1% has slowed money velocity dramatically.

low and middle class workers spend basically everything they earn, those at the top end of the middle class and lower “high end” if you will, save very little aside from 401k contributions, college tuition and rainy day savings.

The very top have most, if not all material needs already met. Any income gains by these folks are likely to be banked or invested in low risk assets. This money is like molasses and has little to no velocity.

The last time I looked, I believe the top 1% earned just under 40% of the nation’s income, so it’s hardly any surprise inflation is subdued.

No, am not sure where you would get a 1/18th measure. The monetary velocities are down 20-40% from their peaks. A tripling of M from 1 to 3 combined with a 40% decline in V would see a net 80% increase in P if Q were constant:

1Mx1V = 1PxmQ

3Mx.6V = 1.8PxmQ //Q being constant

However Q is not constant over the last 5 years which will be a factor in computing the PQ side of the equation.

The problem with the articles’ analysis is believing that the CPI to Money measurement is direct inflationary comparison. Velocity and Goods also must be factored and giving the precipitous drop in V over the last 15 years, it is clear the article is missing this critical factor.

Josh,

Honest question: Why the precipitous drop in V? Is V directly related to the M1 Multiplier? I’ve heard it said that the multiplier doesn’t exist. I’m not so sure that’s true. Then again, the M1 multiplier has been below 1 for quite some time. Any thoughts?

Nanute the Novice.

Steve, very well written reviewing a couple thousand financial articles a week this is one of the most enlightening and effective reads in several years.

My thoughts are would you please enlighten me or us on the mechanism or potential correlation between the Fed Cash of Primary dealers increase and the SP500 increase. The chart does illustrate that there is a correlation between reserves and the financial market place. Unless I have completely misunderstood this.

Nanute,

That is an interesting question. Carl above believes it is because income and wealth are being hoarded by the top 1%. I believe this is false. From 1983 until 2010 the top 1% went from 33.8% of wealth to 35.4% this is a net 1.6% nominal increase and 4.7% net increase. This doesn’t intuitively seem to capture the 25-40% decrease in velocity.

My view is that the velocity drop is indicative of a risk off attitude by the populace in general. They are spending less on ‘stuff’ because on average we are older, want less risk, have less of a time horizon for investing and earnings, etc. Personal savings has in general increased recently while personal credit has in general decreased.

Baby boomers are retiring at a frightening rate, and their risk appetite is lowered, their consumption patterns change, and the economy slows, all the while youth unemployment is very high and new earners are not coming into the system with enough force or earnings vigor to make up for this.

Great post – especially in pointing out the general, overall failure of economists, academics and financial writers to understand the money system.

I hope you don’t mind this one push – for even further evolution of the real potential of the monetary system as the greatest common that a national economy can possess.

This one push, friendly and constructive in nature, is to ask this question: WHY do we have a reserve-based currency and money system?

The answer, if I may, is a throwback to the gold standard for national currency, and the NEED to hold reserves back then in order to provide confidence against a general currency fail.

Today, all money is created by the private bankers in an endogenous debt-driven conflagration that Friedman described as “the creation and destruction of capital” in his Fiscal and Monetary Framework.

Progressive economists and contributors to monetary science have been calling for an end to this debt-based, temporal, private money system for over a hundred years.

It’s time we paid some attention to how the alternative might benefit our society.

While the avante-garde thinking of IMF researchers Benes and Kumhof in their Revisitation of The Chicago Plan actually do use rservre accounting to prove that public money, issued of a ‘permanent’ nature, can achieve growth without inflation or deflation and pay off the national debt, it is merely due to their use of a DSGE model that required a reserve-accounting presentation. It’s the IMF’s model.

Japanese economist Yamaguchi also modeled the Chicago Plan and the Kucinich reform proposal and found similar results.

But we NEED to move to the next step.

What we issue under Kucinich is REAL MONEY.

When you issue real money – there is no need for reserves of any kind.

Are you ready to take that plunge?

For the Money System Common.

Josh,

Thanks. I don’t want to go off topic and hijack Steve’s comments section. I’m still stuck on the nexus between velocity and the multiplier. Or, is there no link between the two? I think it is also possible that a large private debt consolidation is also a factor with regard to the slowdown. A very influential minority group of political actors are wrongly fixated on the public debt, when in reality it is private debt, coupled with high unemployment, that’s ailing an anemic recovery. Is it a classic case of the “paradox of thrift?”

Nanute,

The money multiplier is strictly a banking measure of required bank liquidity to loans. There is a relationship to velocity as cash comes into a bank, and is loaned out to somebody, which is then spent, so there is some tie to the velocity of the money.

However, the excess reserve measure seems to be a proxy for deposit to loan activity:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/EXCRESNS

It has jumped as well in the crisis. The basic point is that these reserves are not making it out into the economy, lower velocity and bank deposit to loans:

http://www.zerohedge.com/sites/default/files/images/user5/imageroot/2012/12-2/Bank%20Deposits%20and%20Loans%20Difference.jpg

While the fed is pumping liquidity in through various measures, credit expansion and velocity are low which keeps things like CPI down. But because CPI is down, doesn’t mean that monetary expansion isn’t happening.

The zeal to show that the Fed is not causing a monetary inflation, or the threat thereof, may be polluting the discussion a bit.

The Fed is obviously ‘printing money,’ that is being held as reserves. Commercial bank reserves are a long established component of the money supply in a fractional reserve system. It is part of ‘the base’ or M0.

I think it is reasonable to say that not all ‘money’ is equal in its effect on the real economy. This is why the various measures of it exist, M1, M2, MZM. Each type is a progression of money in the system, with various characteristics.

Whether money is created by the expansion of commercial credit or the expansion of the Fed’s Balance Sheet is a variable based on the state of the economy and the Fed’s policy reactions.

I do think that the Fed is not being particularly effective in its policy because the money stimulus looks like a ‘trickle down’ approach. And so many of the indicators are less useful unless you look at the median, rather than the aggregate.

Josh,

I don’t think wealth is the issue related to velocity. Wealth is stored potential to consume. Velocity comes from the action of consuming.

If people are afraid to consume in a 70 to 80% consumption driven economy, wealth may be a factor, but that wealth, potential is created via income.

I have shown there are what I believe are 3 significant moments since the depression of 1929. At that point share of income to the 99% is below personal consumption. Those two line come closer as share of income declines to the 1% in the 30’s. The second recession of 1937 saw a share of income rise to the 1% of 19%. By 1945 the share of income to the 99% finally crossed over personal consumption and the 1% share of income had dropped below 15%. In 1996 the 99% income share again crossed below personal consumption and has been moving further apart since. Also in 1996 the 1% share again was above 15% and has risen to 21 to 24% since around 2005.

Krueger with his Gatspy chart presentation noted the income shift was worth $450 billion in consumption activity most probably (hedging?) achieve through consumer borrowing.

This recession supposedly happened because people were unable to pay their mortgages causing the housing crisis. Either way, they ran out of income and thus the means to address their expenses. And nothing has changed. (Personally, I believe it was the consumer facing $4/gallon gas and heating oil or more in that August that finished it off causing the sudden pull back as the decline had been happening since 8/2006). The masses have been out of income since 1996.

No rise in income to the masses means no ability to take on more debt thus the personal consumption declines. I would venture to guess that the 99% income line and personal consumption lines are now coming back closer together as they were seen to do after the Depression.

@Dan: “I have shown there are what I believe are 3 significant moments since the depression of 1929. At that point share of income to the 99% is below personal consumption.”

Do you have a post on this? Would love to see those time series.

Steve,

This is where I posted the 2 charts: http://angrybearblog.strategydemo.com/2007/12/its-big-one-honey-i-know-it.html

They do not enlarge when you click on them. I have to reload them for this WP system I guess.

I have asked Dan for you address. I used Saez’s data and did a lot of separating that I used in a few posts. I’ll send you the spread sheets.

Using the same data, I posted that the top 1% has been doubling their income faster than the GDP has doubled since the 80’s. A complete reverse of what used to be.

I belatedly discovered this post from a link posted by Mike Norman on RealMoney to support his point that “The Fed is not printing money..”

As it stands, many expect the Fed to hold on to the securities it has purchased until they mature. And for these it has credited the seller of the securities with reserves on which it pays a nominal interest.

Now, there is interest income received on the securities it holds (mostly treasuries and MBS guaranteed by the GSE/Treasury so no need to worry about defaults and loan loss reserves). And from this interest income, the Fed pays interest on the reserves. And the surplus, which is quite a juicy spread, is handed over to the Treasury.

And when the bonds mature, the principal is also turned over to the Treasury.

So, there you have it. Monetization of the government’s debt. AKA Money Printing.

And it gets more interesting.

With MBS, you have private debt, which might also get held to maturity and the interest and principal on these as well are turned over to the Treasury.

This is monetization of Private Debt. AKA Money Printing.

Our deficit this past year would have been $100 billion greater without the Fed direct payments.

So, to summarize:

The Fed buys the bonds.

The Fed re-circulates the interest rcvd from the Treasury back to the Treasury.

The Fed holds the bonds to maturity and again re-ciculates the principal back to the Treasury.

That is the monetization of the Federal debt.

With MBS, it gets much better.

The interest received from the pvt borrower and the principal paid back by the pvt borrower is again turned over to the Treasury.

That is monetizaton of Pvt debt and a windfall for the Treasury.

What else is all this, other than as Paul Volker was quoted above : “in the common vernacular, called ‘printing money’.”

@Ray Kumar: “many expect the Fed to hold on to the securities it has purchased until they mature”

That really is the crux of the matter, isn’t it?

Are these bonds being retired from the market temporarily (basically a multi-year repo), or permanently?

I am greatly impressed with this article but in the end I think you make too much sense out of quantitative easing by the Fed. I am left wondering why the Fed bothers and why commercial banks go along with this retirement of bonds in exchange for reserves. No one seems particularly well served by the whole exercise.

Also, I do believe, in the article and your additional comments you more or less prove, contrary to your purpose, that reserves are closely akin to money – they are an account balance that can be converted into money quickly if needs be.

One, perhaps unintended, implication of the article is that printing money starts looking rather respectable – it should no more be a source for concern, assuming it is properly managed, than QE.