Deep and Long: Private Debt and Financial Recessions

While he (uncharacteristically) doesn’t explain or deploy it terribly well, Paul Krugman points to some very excellent research on the relationship between private debt levels and the depth and duration of (especially financial-crisis-driven) recessions. The Schularick/Taylor Vox EU article is here. The Jorda/Schularick/Taylor paper is here (PDF).

I think the work is excellent in large part because JS&T address one of my pet peeves: sample size and selection. Unlike Reinhardt and Rogoff, who make wild claims about government debt/GDP levels above 90% based on a mere handful of sample points (examples that mostly aren’t representative of our current or recent situation), and unlike the kind of single-country and short/single-period analyses that you see all the time, and totally unlike shameless cherry pickers such as John Taylor (who dares to call 1981 — unequivocally a Fed- and interest-rate-driven recession — a financial crisis) JS&T look at a long-term, representative, multi-country data set culled from:

o Fourteen advanced economies that at least in that sense are representative of the economies that at least I am interested in understanding (i.e., ours). “The share of global GDP accounted for by these countries was around 50% in the year 2000.”

o Over 140 years

o Using a very clear definition of “financial recession” (below).

They end up with a sample of 208 recessions in advanced economies over that period, 35 of which were financial recessions.

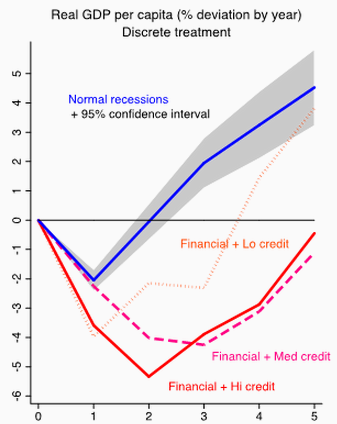

And then they look at multiple lag times (something that is far too often absent from time-series studies): with conditions X in year zero, how do economies perform 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years later? (I rather took this issue to the limit in comparing US and EU growth rates, here.)

Results? I’ll cut to the comment that I just left on Krugman’s blog, with graphics added and some links and editing for your reading pleasure.

…a country’s corporate and financial sectors experience a large number of defaults and financial institutions and corporations face great difficulties repaying contracts on time. As a result, non-performing loans increase sharply and all or most of the aggregate banking system capital is exhausted. This situation may be accompanied by depressed asset prices (such as equity and real estate prices) on the heels of run-ups before the crisis, sharp increases in real interest rates, and a slowdown or reversal in capital flows. In some cases, the crisis is triggered by depositor runs on banks [yes we saw some — Northern Rock — but largely a cause rather than an effect], though in most cases it is a general realization that systemically important financial institutions are in distress. [No names, just initials: Lehman Brothers. AIG.]“

A grateful nod to my fellow contributors on this subject: While I find Jazzbumpa and Arthur’s arguments about private debt and growth compelling, I do not find the single-country (U.S.) evidence that they provide conclusively convincing (for the reasons outlined above, and here [also see comments there]). I am pleased to find that a far more comprehensive and more systematically analyzed data set seems to support their conclusions. JS&T don’t do 20-year lags, so it’s hard to know from them what the long-term growth effects are of excessive private-debt runups. But they certainly display a mechanism whereby such runups could damage long-term growth: by savaging that growth in rare but devastating financial recessions.

And it’s worth remembering who that devastation is visited upon: the middle class and the poor. The rich do just fine.

Recessions are nature’s (and neoclassicals’) way…of keeping the little guy down.

Cross-posted at Asymptosis.

From this point forward, I wish we could refer to public debt as public savings.

I wish we could just stop issuing public debt. It just confuses people.

Steve, thanks to MMT at least I have been converted, and understand the fiat system more clearly. It all started when I was researching QE, how that operated, and what the consequences might be (thus the widowmaker trade on shorting the Yen). Really quite simple when you think about it.

Forgot, to add Steve, it will be a touch sell even to many established economists, and to the conventional thinking about the deficits and what political party was in charge etc…