The Impact of Rebates on Measured Inflation of Branded Prescription Drugs

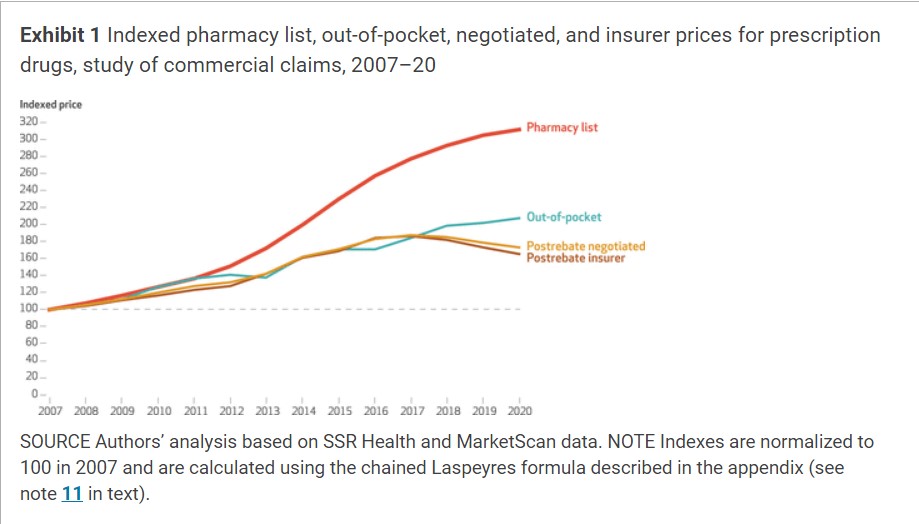

I found this report on Health Affairs a day or so ago. It was long and I spent the last two days condensing it so it could be presented and read on Angry Bear. Briefly, the author(s) detailed four main prices which consist of a List Price, an Out-of-Pocket Price, Insurer’s responsibility price, and the Negotiated price once all rebates are accounted. Exhibit 1 is a quicky study to understand how the authors arrived at the breakdown. Also detailed is the increase in pricing broken down by those elements.

Finally found something which gives a better description of pharma pricing by entity.

Consumer Out-Of-Pocket Drug Prices Grew Faster Than Prices Faced by Insurers After Accounting for Rebates, 2007–20, Health Affairs

Abstract:

This article investigates the complexities of pharmaceutical pricing, with an emphasis on the overlooked aspects of manufacturer rebates and out-of-pocket prices. Rebates granted by pharmaceutical manufacturers to insurers reduce the actual prices paid by insurers, causing the true prices of prescriptions to diverge from official statistics. The authors combine claims data on branded retail prescription drugs with estimates on rebates to provide new price index measures based on pharmacy prices, negotiated prices (after rebates), and out-of-pocket prices for the commercially insured population during the period 2007–20.

What was found? Although retail pharmacy prices increased 9.1 percent annually, negotiated prices grew by a mere 4.3 percent, highlighting the importance of rebates in price measurement. Surprisingly, consumer out-of-pocket prices diverged from negotiated prices after 2016, growing 5.8 percent annually while negotiated prices remained flat. The concern over drug price inflation is more reflective of the rapid increase in consumer out-of-pocket expenses than the stagnated inflation of negotiated prices paid by insurers after 2016.

A 2023 KFF survey reported; eight in ten people in the US found the costs of prescription drugs to be unreasonable. Three in ten admitted to prescription nonadherence because of high costs.1 Recent government interventions, such as the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 and an ongoing investigation by the Federal Trade Commission,2 seek to address rising pharmaceutical prices.

The complexity and lack of transparency in pharmaceutical pricing make it difficult to discern the true costs of drugs.

- One complicating factor is manufacturer rebates, which are discounts on prescription list prices provided by drug manufacturers to pharmacy benefit managers, which in turn may share some or all of the rebates with insurers. More precisely, pharmacy benefit managers negotiate drug prices with drug manufacturers on behalf of insurers. In exchange for discounts, pharmacy benefit managers grant more favorable placement on their drug formularies and steer consumers toward formulary drugs. A 2023 report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found evidence that pharmacy benefit managers structure Medicare Part D formulary tiers to direct sales to drugs with relatively high rebates and high list prices that have a lower net cost for the plan sponsor, but not necessarily for patients.3 Price transparency is limited due to the private nature of these contracts, making it challenging for researchers and government agencies to assess the effects of rebates on prices.

- Rebates are paid to pharmacy benefit managers after purchase. Rebates are not publicly reported and are not reflected in the official statistics from the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the Bureau of Economic Analysis, which are based on transaction prices at pharmacies (the combined payments of the insurer and consumer at the time of purchase).4,5 This differs with how prices are measured in official statistics for other health care sectors measuring actual negotiated prices between insurers and medical providers.6 The differences mean the key measures of pharmaceutical prices used to inform policy makers and the public might not accurately reflect the final cost of drugs.

- Further obscuring measurements of drug prices is neither pharmacy prices nor the negotiated prices reflect what consumers pay out of pocket at the pharmacy. Privately insured people’s copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles are set on the basis of rising pharmacy prices that might not mirror the prices negotiated by insurers. Understanding trends in out-of-pocket prices is particularly important for two reasons:

- First, it may generate diverging impressions of price trends if consumers’ out-of-pocket prices deviate from insurers’ negotiated prices, and

- Second, there are distributional consequences if out-of-pocket prices are rising quickly, as lower-income populations are disproportionately burdened by these payments. In the KFF survey, three in ten respondents found it difficult to afford prescription drugs, but this rose to almost four in ten among households with incomes below $40,000.

- The objective of this study is to enhance public understanding of price trends in the branded prescription drug market for the commercially insured population younger than age sixty-five. We combined extensive data from private prescription drug claims with estimates of rebates. The study covered retail prescription drugs from the period 2007–20 and applied a consistent methodology to measure pharmacy prices, negotiated prices after rebates, and out-of-pocket prices paid by consumers.

Analysis

With these data sources, we constructed four main prices.

- The first was pharmacy list price. The amount paid to the pharmacy (for example, CVS, Walgreens etc.) for a prescription (suppose $100). The cost of the pharmacy list price is shared between the patient and the insurer. Each party is responsible for their share of the pharmacy price.

- Secondly is the out-of-pocket price. The amount the patient is responsible for paying at the pharmacy (suppose $40). Mathematically, the out-of-pocket price is the sum of a patient’s copays, coinsurance, and deductibles toward the prescription.

- After the patient’s out-of-pocket payment, the remaining balance ($60) is the insurer’s responsibility. Because insurers receive confidential rebates (suppose $10), the true price paid by the insurer was our third price, the post-rebate insurer price ($60 − $10 = $50).

- The final price or the negotiated price, is the amount actually paid for a drug once rebates were accounted for ($40 + [$60 − $10] = $90).

In the study, the pharmacy list price and the out-of-pocket price were obtained from MarketScan claims. The negotiated price was constructed by combining SSR Health data with MarketScan pharmacy price data. The insurer price is the negotiated price minus the out-of-pocket price paid by consumers, reflecting the fact that as consumers pay more, the insurer pays less.

Exhibit 1 illustrates price inflation across our four different measures of prices. Pharmacy list prices experienced an average annual growth rate of 9.1 percent during the period 2007–20. However, after adjusting for rebates, negotiated prices grew 4.3 percent annually. In contrast, the out-of-pocket price rose by 5.8 percent annually. Growth in insurer prices and negotiated prices closely followed the growth in out-of-pocket prices until 2016, when both insurer and negotiated prices began to decrease.

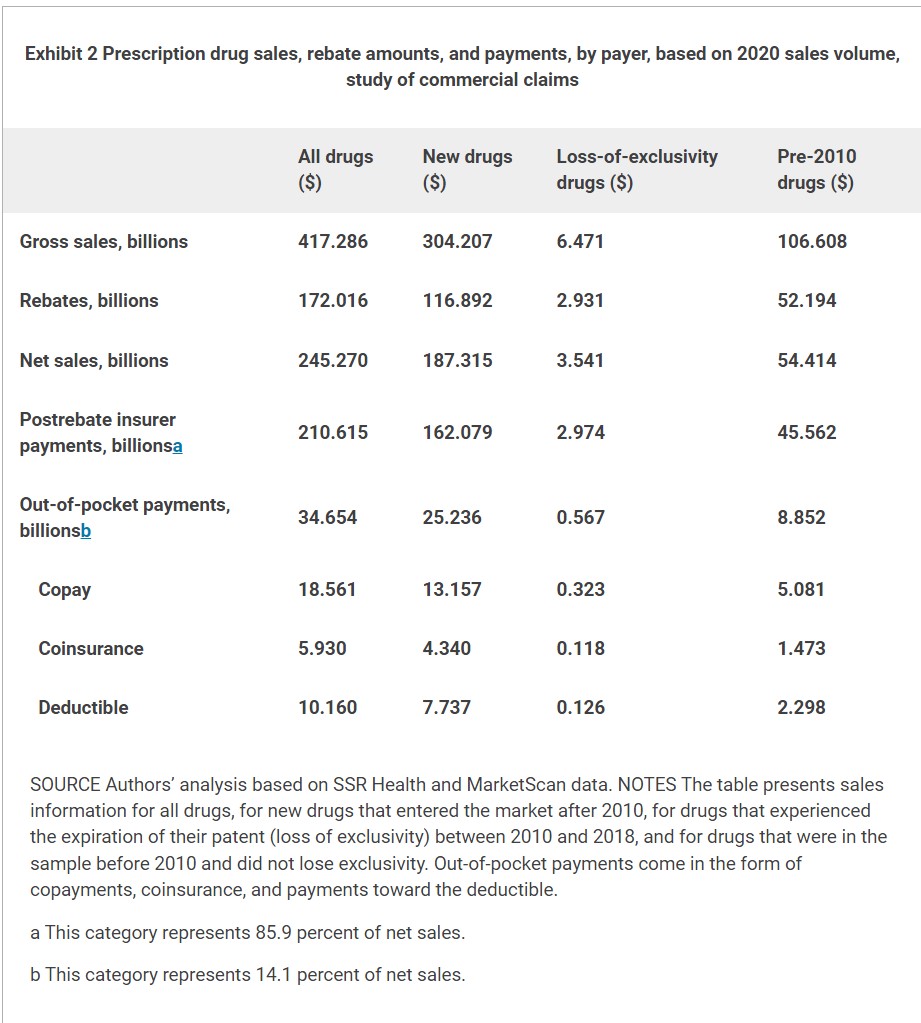

Exhibit 2 shows the types of drugs driving price patterns based on 2020 sales volume. The exhibit lists gross sales, rebate amounts, net sales after rebates, net insurer payments, and net consumer payments. These components are shown for different groups of drugs: all drugs, new drugs launched after 2010, drugs launched before 2010 losing their exclusivity before 2018, and drugs launched before 2010 that did not experience a loss of exclusivity.

Exhibit 2 demonstrates that despite the rapid post-2016 growth in out-of-pocket prices shown in exhibit 1, out-of-pocket payments constituted a minority share of the total cost in 2020, accounting for 14 percent of net sales. In addition, new drugs made up most of the sales, accounting for approximately 75 percent of sales by 2020. Because our price indexes were sales weighted, most of the price trends were driven by new drugs that entered after 2010.

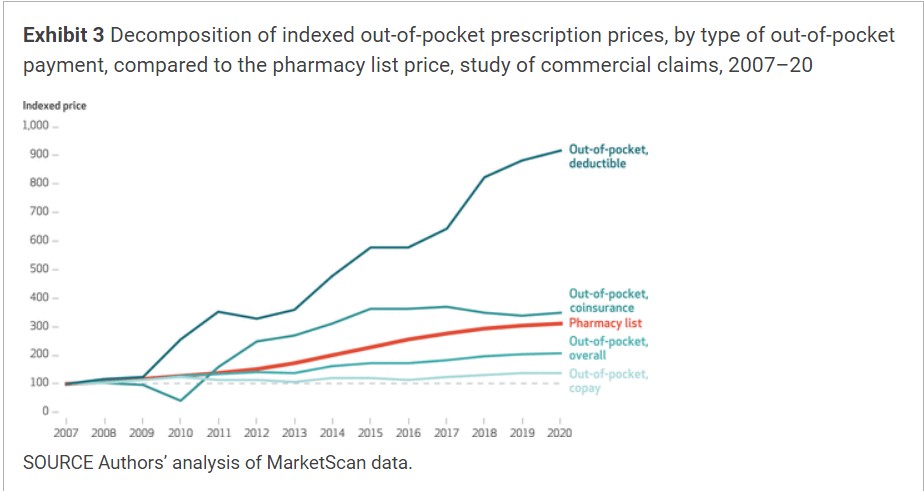

The growth in out-of-pocket prices deviated from negotiated prices after 2016 (exhibit 1). While Exhibit 3 disentangles which aspects of the consumer payments, deductibles, coinsurance, and copays were driving the more recent growth in out-of-pocket prices. Growth in overall out-of-pocket prices seems to have been driven by large increases in coinsurance and deductible payments. Rising pharmacy prices are likely to affect deductibles and coinsurance payments, which are typically set on the basis of the pharmacy list price.

Results of several robustness checks were similar to the findings in our main analysis (see appendix exhibits A6, A7, A9, and A10).11

Discussion

The findings have important implications for economic measurement and policy discussions. The study highlights the impact of rebates on measured inflation for branded prescription drugs. Rebates are not currently reflected in official statistics.

Between 2016 and 2020, out-of-pocket prices experienced faster growth than prices faced by insurers, after commercial rebates were accounted for. Concerns about price growth align more closely with the persistent increase in out-of-pocket prices than the recently stagnating growth in negotiated prices. The divergence in prices after 2016 raises concerns about the disconnect between external estimates of negotiated prices and the actual costs borne by consumers. These results are consistent with the high cost sharing reported by the GAO,3 as well as an analysis by Kai Yeung and colleagues.9 It suggests that rebates can lead to a growing gap between negotiated prices and out-of-pocket prices, as rebates drive down negotiated prices while increasing pharmacy prices drive up out-of-pocket prices. We demonstrate these patterns have extended to commercially insured Americans.

New drugs make up the majority of the market for branded drugs and have high list prices and high rebates that continue to grow over time. Consumers are operating in an innovative and expanding pharmaceutical market where they are spending more on new drugs and facing growing out-of-pocket expenses based on less transparent prices as rebates swell.

Our findings on drug price inflation are complementary to results reported by Pragya Kakani and coauthors8 and Inmaculada Hernandez and colleagues7 demonstrating that rising list prices do not translate to higher net payments to manufacturers. We too concluded that after-rebate negotiated payments stagnated after 2016. Rising list prices do affect consumers. Our finding that prices for out-of-pocket payments in the commercial insurance market grew more quickly than negotiated payments complements the GAO’s findings that for many drugs, Medicare beneficiaries are paying more out of pocket than insurers are paying, net of rebates.3

We found the increasing out-of-pocket expenses arose from increasing deductible and coinsurance payments. This implies consumers will experience a heterogeneous cost burden, depending on their drug plan’s formulary structure. Although consumers with high deductibles or coinsurance may experience high out-of-pocket spending growth, consumers with a low deductible or capped copays appear to be shielded from steep pharmacy price increases.

Rising out-of-pocket prices can disproportionately affect households with lower incomes who may select into high-deductible plans with low premiums, not anticipating higher cost sharing at the time of purchase. We found deductible payments drove rising out-of-pocket spending, so rebate-induced price distortion may be especially burdensome for low-income households. Moreover, prior research has found that patients with chronic diseases pay more out of pocket while under high-deductible health plans than do their counterparts with low-deductible plans.13 Growing rebates and list prices may exacerbate the burden of plans with high cost sharing even further.

Conclusion

Understanding the dynamics of pharmaceutical pricing requires controlling for the role of rebates and considering both negotiated prices paid by insurers and out-of-pocket prices paid by consumers. The study contributes to the literature by combining comprehensive claims and rebate data sources to investigate price trends among key stakeholders in the pharmaceutical supply chain.

Overall, the findings emphasize the importance of accurate measurement to inform policy discussions regarding prices in prescription drug markets. Statistical agencies such as the Bureau of Economic Analysis and the Bureau of Labor Statistics have been working on this issue. The Bureau of Economic Analysis, for instance, has begun to integrate rebates in experimental disease-based statistics.14 However, rebates have not been accounted for in official inflation measures. Given the data limitations, more work is needed to provide a complete and accurate picture of how pharmaceutical prices are changing in this sector of growing economic importance.

Consumer Out-Of-Pocket Drug Prices Grew Faster Than Prices Faced By Insurers After Accounting For Rebates, 2007–20 | Health Affairs, Justine Mallatt, Abe Dunn, and Lasanthi Fernando

Did the study include non insurance sales for patients without coverage? I know it included pharmaceutical rebates but what about people who use GoodRx and mail order suppliers from Canada?

Jack:

That is not considered.