The Week Ahead: Conventions Past

by Joyce Vance

Civil Discourse

Twenty twenty-four finds the Democrats nominating a Black woman to run for president. Said another way, a woman will be nominated by a major party as its candidate to be the president of the United States. The first time in our history in either instance.

This will all take place in an upcoming convention.

Kamala Harris is eminently qualified by virtue of both experience and temperament; if you haven’t recently rewatched her telling Mike Pence “I’m speaking” during the 2020 debate, you owe it to yourself to watch.

Some conventions garner less attention even though they are all notable. Because every four years, Americans come together to practice democracy. It’s remarkable that we have been doing it for over 200 years. And even more remarkable after the last election and the storming of the Capitol.

A couple of weeks ago I was doing some deep cleaning and came upon my father-in-law’s credentials from the 1972 Democratic Convention in Miami. That was the year the incumbent, Richard Nixon, beat South Dakota Senator George McGovern. McGovern ran on an anti-Vietnam War platform. “Within 90 days of my inauguration, every American soldier and every American prisoner [in Vietnam] will be back home in America where they belong.” This he told to the convention. He lost in one of the worst defeats in electoral history, 520-17. McGovern carried only Massachusetts and the District of Columbia.

ironically, he handled the Democratic convention masterfully, winning on the first ballot against two challengers. Alabama’s segregationist governor, George Wallace, running as part of the “anyone but McGovern” movement, edged out Hubert Humphrey just slightly, 371 votes to 345, but McGovern overwhelmed them both with 1319 votes before going on to defeat in the general election.

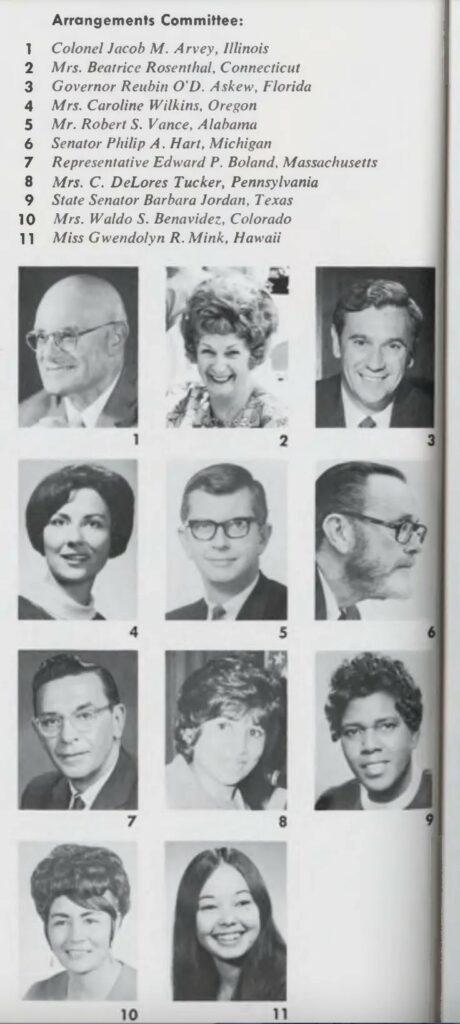

My father-in-law’s role in 1972 was a modest one. The head of the Alabama Democratic Party (most emphatically not part of the Wallace faction), he served on the arrangements committee, which promoted the important improvements it made over past conventions: low-cost housing, modern security enforcement, and the largest communications network ever.

Although women outnumbered the men on the committee, there was only one Black member; then a state senator in Texas. Barbara Jordan went on to become the first southern Black woman elected to the House of Representatives. Four years later, Jordan was mentioned as a possible running mate to fellow Southerner Jimmy Carter. Although she wasn’t selected, she became the first African-American woman to deliver a keynote address at the Democratic National Convention.

Look at those photos. We have made so much progress. Instead of letting MAGA denigrate our country and our accomplishments, we should be embracing how far we’ve come. We have miles to go, but we have come so far.

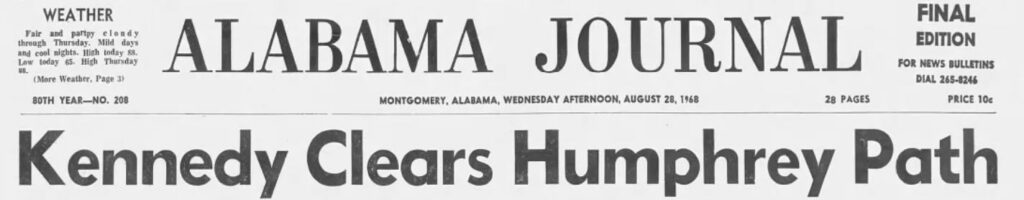

At the 1968 Convention, Alabama made some history that connects to where we are now.

The Alabama Journal reported it like this:

“One proud moment came in 1968, when Judge Vance led the state’s delegation to the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, the first Alabama delegation to include blacks.”

Before that, no Black delegate had represented Alabama Democrats at the convention. And even that year, it was a close call, pushed past an angry George Wallace.

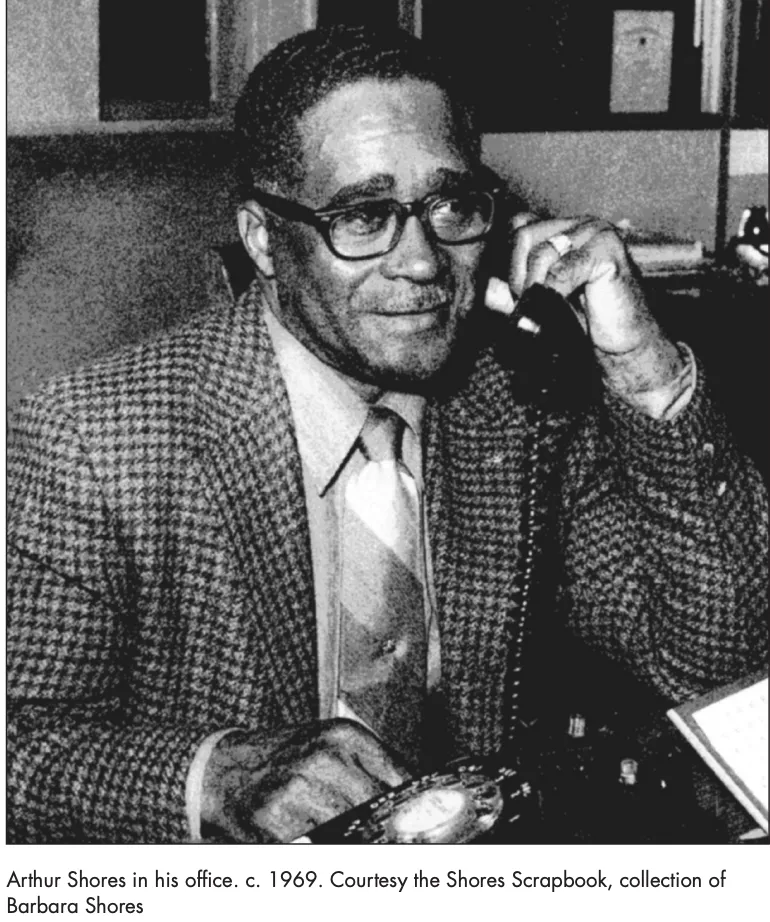

One of the delegates was Arthur Shores, a prominent Birmingham civil rights attorney, whose home was bombed twice in retaliation for his role in the Civil Rights Movement. His daughter, Helen Shores Lee, went on to become a circuit judge on the same court my husband served on in Jefferson County, Alabama. Whenever I saw them working together, I thought about how happy and proud that would have made their daddies, who had worked together to summon a world where it would be unremarkable for a Black woman to be a judge and work alongside a white male colleague.

It is such a simple story, lost to history for the most part, but I think about the courage it took for Mr. Shores to go to the convention despite the violence his family had experienced. His daughter Helen told me many years later how frightened her mother was about him going—but also proud. People like Arthur Shores make history, make the future possible, even when they aren’t widely remembered.

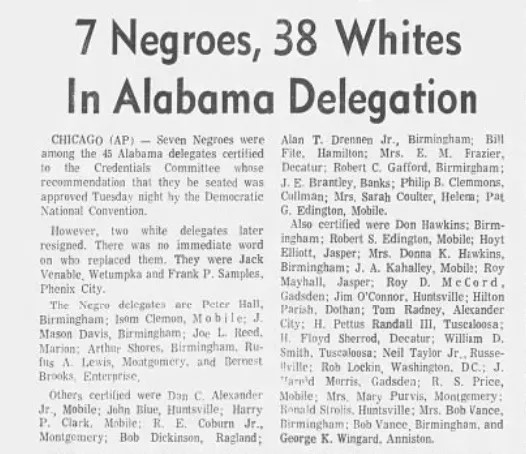

There were some shenanigans involved in the maneuvering in 1968 that I’m not sure I ever got entirely straight—perhaps involving some delegates stepping aside at the last minute so the first Black delegates could serve. Two white Democrats from George Wallace’s camp resigned in protest when the Black delegates were seated.

The public history I’ve found, a rather sanitized version of what I was told over the years, reflects that, “Vance split with many southern Democrats by opposing segregation. His rise hurt Gov. George Wallace’s political faction, and Vance famously sparred against Wallace’s proposed delegates (which included noted segregationist Eugene “Bull” Connor) for the 1968 Democratic National Convention (DNC) to prevent it from being seated at the convention … Ultimately, the Vance delegation was seated at the convention and it included a large faction of Blacks as the first ever interracial delegation from Alabama at a DNC.”

Alabama was part of an emerging trend:

And it wasn’t just Alabama’s delegation that was taking baby steps toward racial equality in 1968. They were long overdue and slow in coming, but deeply important. Civil rights attorney and businessman Vernon Jordan wrote about it:

The courage of the Black delegates who faced down irrational hatred, often at great personal risk, to attend the convention and demand their place in the process is a reminder that we can all summon the courage to do whatever it takes to defeat MAGA at the polls this fall.

The stories of the conventions are stories of courage—quiet courage that frequently goes on to be forgotten. There’s another one from 1968. Channing Phillips, who is mentioned in the paragraph above, was the DNC chairman for the District of Columbia in 1968. In an attempt to gain recognition for the District, which had no representation in Congress at that time, an effort was launched to nominate him at the convention as a favorite-son candidate for President. His son, also named Channing, who served with me as a U.S. Attorney in the Obama Administration, told me, “It was a symbolic gesture, of course. He was nominated by Philip Stern, while John Conyers gave the second nominating speech. As a result, he earned the distinction of becoming the first black to be nominated for president by a major political party.”

Here we are, looking back at Channing Phillips’ symbolic gesture in 1968 and forward to a week that will culminate with Vice President Kamala Harris becoming the Democratic nominee for the presidency, honoring the service and sacrifice of all of the people who came before her, and helping to move our country forward, a few steps at a time. There will always be work left to do. It wasn’t until 2000 that Alabama’s Democratic delegation included the first openly gay man. But we are going forward. We are not going back.

The week ahead is a week for optimism. Not only will it signal the changing of the guard to a new generation of leadership in the Democratic Party, the Harris campaign is giving off strong vibes that it fully understands the threat to democracy that Donald Trump poses. On the heels of our post last week about the lawyers gearing up to address Trump’s certain efforts to prevent certifying the results of the election—of course, only if he loses—the campaign has announced that it has assembled an unparalleled election protection team, a Justice League of lawyers who know how to protect voters’ rights and election outcomes.

Democratic super-lawyer Marc Elias, who was the general counsel for Harris’ 2020 primary campaign, will focus on election recounts, which is where a lot of the action is likely to happen. His phenomenal successes in court after the 2020 election and aggressive efforts to stop voter suppression in court since then bode well for the campaign’s state of preparedness.

Marc was our guest for Five Questions in March of 2023. This question and answer seems even more important now than it did then:

Joyce: In the run-up to the 2022 midterm elections, election deniers running for key statewide offices like Governor and Secretary of State posed a serious threat to our democracy. Fortunately, most of those candidates went on to lose their elections. As you look ahead to 2024, what do you predict will be the greatest threat to our democracy during the next election cycle?

Marc: The shamelessness of today’s Republican Party is arguably the greatest threat to our democracy as we look ahead to 2024. Democracy only works when we all share certain core values and a common decency, regardless of our party affiliation. Unfortunately, today’s Republican Party is committed to undermining faith in elections with evidence-free conspiracies about voter fraud, while targeting minority voters with gross acts of suppression and intimidation. And I worry that Republicans will continue to target the vote counting and certification process.

We are in for a convention and a campaign to be proud of: American joy instead of American carnage. Progress can be slow, and sometimes painful, but it is progress nevertheless. This week, we get to watch history happen.