Modeling the Wealth, Income, and "Saving" Effects of Redistribution: More is Better?

Update: More expansive discussion of this model with more graphics, here.

Update 2: There is a revised and corrected version of the model and spreadsheet here, with discussion.

It has long seemed to me that redistribution is, for some reason, necessary for the emergence, continuance, and growth of large, prosperous, modern, high-productivity monetary economies. No such economy has ever emerged absent large quantities of ongoing redistribution. There are no exceptions; every such economy on earth engages in it on a large scale. The Economist recently devoted a whole special section to the need for Asian countries — notably China — to develop such systems of social redistribution in order to make the move from “developing” to “advanced.”

That’s the big-picture empirics. What I’ve been missing, have been unable to find, and have been struggling to conceive, is a straightforward, intuitively convincing economic model (mathematical or at least arithmetic) to explain this fact theoretically.

Paul Krugman says that thinking in terms of models will make you a better person. I want to be a better person.

I think I may have finally created such a model. (I’m feeling better already.) It’s a very simple dynamic simulation model (set it up, plug in parameters, and watch it run over the years), and it’s purely monetary. It makes no attempt to model the real economy of production and trade in real goods. It makes no distinction between consumption and investment spending; there’s just spending. It doesn’t require a theory of value, or of capital, or of profits. It simply assumes that production and trade happen, and that they yield a surplus. You can imagine that surplus as consisting of new real assets, or being embodied in new financial assets that are representative of those real assets. It doesn’t really matter.

The model is based on one and only one behavioral assumption: declining marginal propensity to spend out of wealth. (Something I fiddled with previously, here.) That in turn is based on the declining marginal utility of consumption (the millionth dollar spent yields less utility than the first). The assumption, which seems safe both empirically and theoretically:

Rich people spend a smaller portion of their wealth each year than poorer people.

In this model each person’s spending is replaced each year by income (with a surplus), but the spending is determined by the person’s wealth. It assumes that people expect the income to replace the spent wealth, but they’re not certain that it will, always. So they (especially those with low income/wealth) are facing a tradeoff between present spending and long-term economic security. Different wealth/income levels have different propensities to substitute one for the other.

This is basically looking at spending and income from the opposite direction of most such models. Here, spending drives aggregate income (all spending is income, when received), rather than spending being determined by income (which is how we tend to think about individuals).

The rest is just arithmetic.

Here’s the basic setup, with a population of 11 people. The spreadsheet is here (Google Doc version here); you can change of the numbers and see the results.

I’m assuming 0% inflation for simplicity.

One person has $1 million.

Ten people have $100K each: $1 million total.

The rich person spends 30% of their wealth annually ($300K to start).

The ten poorer people spend 80% of their wealth annually ($80K each, $800K total, to start).

Through work/production and gains from trade, each person gets 5% more income annually than they spend. I’ve black-boxed that whole surplus-creation process; it just happens. I’ve set it up so that income (including the surplus) is distributed to the population proportionally based on how much they spend. It’s a somewhat arbitrary choice (I had to make some choice), but since people’s incomes and expenditures do tend to correlate fairly closely, it doesn’t seem like a nutty one.

The additional money for this annual +5% would come from new bank lending and/or government deficit spending and/or Fed money printing and/or trade surpluses with other countries. Choose your monetary model/paradigm; in any case the surplus is monetized via trade and the financial system.

So no, Income ≠ Expenditure (or vice versa), unless you include purchases of new financial assets in “Expenditures.” Absent those purchases/receipts, Income is 5% greater than Expenditures. That’s what surplus from production/trade is all about, how it plays out in an economy that includes monetary savings.

Now add this: Some percentage of the rich person’s wealth is transferred to the poorer people every year (by the ebil gubmint man).

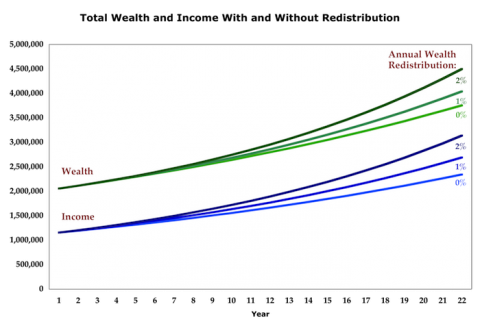

Does that wealth transfer make everyone wealthier, or poorer? Here’s the result with the numbers I set out above:

In this model, taking money from the rich and giving it to the poor make us more prosperous in aggregate, raises all boats, makes the pie bigger…you’ve heard all the metaphors.

Explanation below the fold.

The arithmetic, and the theory, is simple:

The arithmetic, and the theory, is simple:

1. Redistribution results in more spending (because of declining marginal propensity to spend from wealth)

2. More spending spurs more production

3. More production (and trade) produces more surplus

4. Surplus (monetized) is the source of monetary savings

5. Bonus: More savings (wealth) results in more spending. (Note the exponential curves.)

6. Repeat loop.

The result seems to be an apparently counterintuitive, but on consideration very obvious, conclusion:

Saving doesn’t cause saving. Spending causes saving.

The preceding is halfway tongue in cheek. It points out how problematic the word “saving” is in a monetary context. Saving some of this year’s corn crop is straightforward enough — eat less of it. Money makes it into a far more complicated concept, cause you can’t eat money.

I would say instead:

Spending causes accumulation, because it spurs production and trade, resulting in a surplus. That surplus is what allows for accumulation.

So we want more spending, and less so-called “saving.” Some people call it money hoarding, but that’s confusing too. The best synonym for monetary saving is “not spending.”

I’m with Nick: we should stop using the word saving.

More monetary saving by individuals (the word works fine for individuals) — spending a smaller proportion of their wealth on real goods each year — results in less accumulation in aggregate.

Faithful readers will recognize that this purely monetary model sidesteps and obviates the need for the conceptual quagmire associated with S = I = Y – C — a construct which, in its effort to go in the opposite direction from mine and model a barter, real economy devoid of monetary savings, arguably makes it impossible or at least very difficult to think cogently about how monetary economies (i.e. all economies) work.

But how about sharesies? Is it fair? Here’s how it plays out:

| 20 Year Change in Income/Wealth | |||

| Redistribution | Rich Person |

Poorer People | All |

| 0% | 35% | 119% | 96% |

| 1 | 10 | 165 | 123 |

| 1.5 | 0 | 192 | 139 |

| 2 | -10 | 221 | 158 |

At 1.5% redistribution in this model, the rich person’s income, spending, and wealth all stay the same over time (remember: no inflation here), while the poorer people’s income and wealth almost triple, and overall wealth and income more than doubles. Seem fair to you? Pareto devotees please comment.

I know exactly where everyone’s going with this: incentives and behavioral responses. And I have to admit that I did make one other behavioral assumption here: that there are no other behavioral responses.

Giving a bit less money to the rich person will give slightly less incentive to work. But at the same time it’s giving ten poorer people far more incentive to work. You do the math. (This all before we get into issues of substitution vs. income effects at different wealth and income levels, something I won’t even begin to address here.)

Whatever combination of behavioral effects one might posit, I would suggest that the burden of proof lies with the positor to demonstrate, empirically, that those effects are sufficient to overwhelm (or supplement?) the inexorable arithmetic of compounding that’s at play here.

Finally, note that this model doesn’t even touch on aggregate utility delivered under each regime. Since the spending of the poorer people is split among ten — each spending $80K/year to start — a larger proportion of that spending is on necessities like food, clothing, shelter, health care, and education. I think all economists will stipulate to the proposition that those purchases yield higher utility per dollar than a family’s purchase of a third car or a fourth TV. So the graph above greatly understates the higher aggregate utility provided by redistribution, and the table either understates the utility gains by the poorer people, or overstates the gains by the rich one. (It would be easy to add a somewhat arbitrary formula to represent that effect graphically, but I’ll leave it to your imagination.)

And: this utility effect would serve to multiply the incentive for poorer people discussed in the previous paragraph, giving the ten people even more incentive to work.

I’m rather taken with this spending + surplus = income dynamic approach to modeling. (But I would be, wouldn’t I?) I’d be delighted to see how others might analyze and display results using various parameters, and how they might adjust, improve, or dismantle the model. In particular: are there obvious, gaping flaws here?

Cross-posted at Asymptosis.

“redistribution” is at least as problematic a word as “savings”

It carries the clear connotation, and certainly to the economic right, that initial distribution of gains is governed by some relationship with productivity and it’s inputs with the Invisible Hand doing the handing out. A better historical reading IMHO is to recast this in terms of power over outputs.

In the standard model “redistribution” implies some artificial redivision and so is almost always distortionary. Under the power model the distortion comes at initial distribution and is corrected for actual efficacy, efficiency, and equity through an inherently messy political process.

Just not less messy than the forces of Capital calling on the military and police powers of the State to forcibly suppress wages.

There was nothing Invisible in the Hand of the Roman with his Gladius, the Samurai with his heirloom sword, or the Lancers at Peterloo. Given the historical record the idea that distribution or you will redistribution is just some neutral outcome of Natural Law is at best special pleading by the employers of the swordsmen and lancers and Pinkertons.

Savings are also a proxy for autonomy/influence.

Unlike consumption goods, the marginal utility of savings/influence does not decline.

I think it needs to be framed this way. The government will provide a certain level of spending that goes to the general population, so rich people have richer consumers (general population) to sell products and services to.

More people with health coverage allows for a bigger market for doctor’s to sell to – assuming doctors and other providers can make a profit and have opportunity to grow their wages through innovation and hard work.

If most of the population falls behind then rich people can’t sell as much stuff.

Steve,

I am bothered that in your model everyone also becomes richer by spending more of their own wealth.

Steve

I agree with your conclusion (that is also the evidence in your citations), and I have been guilty of building models myself. but without thinking about it too hard i am first, a little suspicious that you built the outcome into your assumptions when you said everyone will get more than he spends.

also, i am not sure the rich don’t “spend” their money… investing it is spending on harder things. also, as Bruce points out, the rich spend a lot of their money not on consumption but on maintaining their power.

like i said, haven’t thought much yet, may not even get around to it, but i offer these thoughts in case they help.

Interesting model there Steve. I played with it.

You need at least 103.5% to the wealthy person to assure their income/wealth grows. In 22 years they see a 1% growth.

At 103.5% for the one, the poor need at least 99% with the 1% transfer to see a gain (at 98.75 it’s a loss). They see a 4% gain in 22 years.

At 98% for the poor, the transfer has to be 1.65% for them to see a gain of 1%. However the rich person at their 104% sees a 11% loss.

If the rich person sees a gain of 105.6% with the minus 1.65% transfer they see a 1% gain.

I would say your model is showing just how much less efficient a system becomes as the poor’s income gain goes negative. There has to be a greater transfer for the poor to gain which requires a greater gain for the rich not to lose in order for the entire model to gain.

Isn’t this in part exactly what we have been experiencing resulting in an ever declining GDP growth rate? We have not made the transfers in an amount large enough to make up for the decline (negative income growth) of the poor vs the income share gain of the rich. On top of that, I have shown that the income gains to the rich have been so great that they are actually pocketing money faster than our economy can produce it.

Not to make Coberly angry, but if Steve’s model is solid then we really need to be “soaking” the rich right now if we are to ever return our system to something approaching what to many believe was a magical invisible market hand.

All: I understand the rhetorical issues surround the word redistribution, but here I’m more interested in the model itself.

“Saving” is a different issue. I’m here suggesting that aggregate the notion of aggregate monetary “saving” as generally employed in economic discussions is a problematic or maybe even incoherent concept.

@Arne: “I am bothered that in your model everyone also becomes richer by spending more of their own wealth.”

Actually, they spend less than their income each year (by construction, in this model), so their wealth increases each year.

@Coberly: “you built the outcome into your assumptions”

Something I was aware of, though I’m hoping that it is not, in this case, a fatal flaw.

“everyone will get more than he spends”

In aggregate, in a growing economy producing surplus, that must be so. The suggestion that all such surplus (and income, in fact) is equally divided (here based on spending) is clearly a stylized technique, one that could me more realistically worked out in an elaboration of this model.

“the rich spend a lot of their money not on consumption but on maintaining their power”

Note that this model doesn’t distinguish between consumption spending and investment spending. Spending on maintaining power I’m thinking generally means hiring people, which is in the class of “real world goods and services” as opposed to financial assets. So it’s spending in this model, and what it produces is immaterial to this model.

“i am not sure the rich don’t “spend” their money… investing it is spending on harder things.”

Be very very clear on what you mean by “investment.” In the national accounts, “investment spending” is spending on new fixed assets: structures, equipment, and software. Purchases of financial assets (including existing residences) are not even considered in the NIPA tables — they’re asset swaps (bank deposits in exchange for bonds, etc. etc.), not purchases.

Becker

don’t see how you could make me angry. but “redistribution” is hardly the answer to declining share of wages. how about unions? how about more government actual work as opposed to more welfare.

i am all for welfare when needed. i think a psychology that reaches for taxes and welfare as its first and only idea is as doomed as an “economics” that refuses to tax or even regulate the rich.

Steve

i couldn’t agree with you more about financial assets not being investing.

without going back and reading it again i can’t say for sure, but it seems to me that it was your assumption that the rich don’t spend their earnings. if you meant they gamble or invest in financial assets, you should make that clear. all i was saying was that a lot of their “spending” might escape what your reader thought of as spending.

i would also argue that an economy that requires the rich to spend a lot for protection… including the military… is an economy that will eventually die from lack of real growth. i’d far rather pay shoemakers than armed goons in order to achieve higher GDP or even higher wages for “workers.”

Steve methinks you ignored my specific examples.

Your typical man at arms in early modern, medieval and classical times was paid to extort surplus value out of local peasants mostly to buy luxuries from distant markets for themselves and their masters. And those luxuries as often as not we’re extracted from those suppliers’ local labor force by similar extortion methods.

I suppose naive Ricardans could derive from this some world comparative advantage that made everyone on average richer. Seems to me that among other matters this loses track of the inefficiencies in early and pre-modern luxury trade, which for example were tough on various beasts of burden and traction (humans and animals alike).

Anyway I have a hard time viewing the Peterloo Massacre as the simple hiring of goods and services of lancers by capitalists. And you could multiply similar examples of wage suppression endlessly across human history and cross-culturally.

Exploitation and economic efficiency only incidentally starting with the same letter ‘e’.

Let us not forget that the whole *point* of a market economy is redistribution of wealth — i.e., the redistribution of wealth from consumers to producers in exchange for the goods produced by the producers. Producers make a profit which they pocket, thus a market economy will in absence of some transfer of wealth from producers to consumers eventually transfer all wealth to producers.

I could model all this, I suppose, but the fact that market economics is all about redistribution of wealth to begin with is the salient point. To whine about “redistribution of wealth” only when it is perpetrated by government, rather than by the market, is to be a hypocrite. The fact that we don’t have any free markets on planet Earth — e.g., the reason we have more consumers than producers is because production happens in China today due to government action there — is probably equally salient, and renders the blather about how some theoretical free market construct will solve the problem so much hot air.

-BT

BT your comment while thoughtful enough totally ignores the fact that there are traditionally two categories of ‘producers’, those who supply labor a d those who supply capital. And who are orthogonal to your producer/consumer distinction.

Perhaps I didn’t read Steve close enough, but in the mental sphere I operate in (mostly historical) ‘redistribution’ is mostly the result of a tension between capital and labor inputs compared to subsequent distribution of gains from that productivity. or redistribution as you will.

Your formulation to me concedes too much by far to the putative wealth and job creators, I.e. capitalists, while perhaps reducing labor to passive consumers deploying their Invisible Hand marginal labor productivity.

If this is unfair then my bad.

Bruce, my point perhaps was that the traditional formulation applies to a theoretical economy that does not exist anymore (if it ever did), not to the actual real economy which exists here today in the United States. Creating models of imaginary economies is perhaps amusing, but of limited utility in modeling income redistribution in a modern economy, where market forces such as economies of scale, market consolidation, and elimination of competition (not to mention that a large employer has far more market power than a single individual employee, and unions are basically dead here) tend to drive wages down and excess profits (defined as those which merely get shoved under a perhaps virtual mattress rather than recirculated back into the real economy) up. The question then becomes of how to get that money out from under mattresses and into the real economy again, since it has all been redistributed upwards by market forces. The traditionalist’s claim that an individual employee in the workforce has the same market power as a giant megacorporation and thus the market power of individual employees will accomplish this redistribution back downwards to consumers is a typical claim made by theoretical economists pushing pure-market solutions, but I am more concerned with the real world, not hypothetical worlds of pink unicorns and cotton candy trees.

Redistribution is real, and is a natural part of all modern economies due to the necessity of corporatization (necessary in order to aggregate the billions of dollars of assets needed for, e.g., a modern silicon chip foundry) which in turn gives market power to employers that is not enjoyed by employees. To ignore this market redistribution and focus only on government redistribution as “evil” is to ignore half the equation. To summarize, a modern economy *must* have government redistribution of mattress money back into the real economy, or it will eventually grind to a halt Great Depression style as a critical mass of money ends up under (virtual) mattresses rather than in circulation.

Badtux

I am generally on your side (and I didn’t understand Bruce’s objection at all) but I think you make a very serious error:

you seem to regard “wealth” as “money.” i’m pretty sure even “most economists” (a group i generally disparage) think of “wealth” as the (exchange of) goods and services of which money is only the grease on the wheel, so to speak, no more “wealth” than the notation in the account book or the “worthless iou” we hear so much about.

this doesn’t change your conclusion, but i think you would need to track what “the rich” are doing with “their money” in order to even be in the same argument as Steve. (which also i think has fatal flaws, but i don’t want to spoil Steve’s fun while something good may yet come of it.)

Bruce

my not understanding your last comment is not a put down of you. if anything it is a putdown of me.

i haven’t read all the stuff you have read. but i tend to think that at least the more “theoretical” parts of that tend to lead to people chasing words around the table and not focussing clearly on what is happening in the real world… or the one i live in anyway.

BT

Well I think the fundamental problem is that the economists who developed both ends of liberal economics, that of Marx and that of Chicago or Neo-classical or whatever knew fuck all about actual modes of production prior to the rise of northern European capitalism. And this true whether examined on a historical or spatial axis. It is they who are starting from the Unicorn World that never actually wasin existence.

For example Steve aummes a marginal disinclination to spend as income rises. “Simple”. The problem is that it doesn’t track the actual behavior of economic elites in pre-industrial times. And ignores the historic reality that the elites of capitalism were by and large drawn from a different social and indeed religious class that indeed valorized thrift and disdained display. And in so doing quite consciously were in reactionto the elites of their own day and of most centuries prior who valorized display and disdained thrift. And as a result more typically spent up to and well beyond their traditional sources of income. Making Steve’s model moot outside a tightly restricted historical mileau, albeit one that has become dominant due to the triumph of first British-Dutch capitalism and then Anglo-American hegonomy.

Similarly BT makes a contrast between an economic system that systematically suppresses wages and sees market concentrations as TYPICAL of a modern economy and CONTRASTIVE to the traditional economy that preceded it. But if that traditional economy was in fact tightly constricted in both time and place and if you saw that same sort of wage suppression and market concentration outside those spaces under more general conditions the argument that suppression and concentration are a specific consequence of the “modern economy” falls to pieces, a strawman blown I to the wind by examination of the actual mechanisms of the actual modes of production prior to Smith, Marx or whichever 18th or 19th century NW European theorist you are appealing to. Remember the early founders of Economics thought and referred to it as a branch of Moral Philosophy and so much closer to what we would call Psychology than Mathematics.

And the result among moderns is the scarce concealed disdain for history and a privileging of theoretical math driven models (such as yours and Steve’s) over historical evidence that casts doubt on it. That is the “limited utility” might in fact be on the other foot. And the “actual real economy” you see operating may be working under similar fairy tale rules as the “Unicorn” theories you dismiss out of hand.

Bruce

now THAT i understand.

i would only add that “theoretical mathematical…” is a branch of religious or moral reasoning.

I think I might add that the “thrift” and “non display” attitude of early capitalists at least was, first, of short duration, and second tied to a point of time in the deveiopment of capital where “thrift” turned usefully into “investment”, so those capitalists were quite busy spending what they “saved.”

i believe… could be wrong.. that we have reached a point where “capital” generates its own “savings” for investment, and rich people have nowhere much to go with their money than to gambling games, where as long as the “money” stays in the game it is no more money than the chips on the table in a casino.

and this of course reminds me of what the rich were doing just before the invention of capitalism…

but here i await your more informed account of history.

Coberly, the confusing of wealth with money is indeed an issue, and my apologies for sloppiness in a late night blog posting, I’m not usually that sloppy.

Bruce, the problem is that the rules change on a regular basis, so any model we come up with has to be regularly tested against reality to see whether it is valid. One problem is that we cannot easily test models in economics the way we test models in other fields. I recently observed the performance of a complex system in The Real World(tm) where upon performing various experiments it was apparent that upon the workload reaching a certain point, the performance of one component began to converge upon O(n) rather than upon O(1) as designed. As a result of those experiments, a buffer cache hash table was adjusted to have more buckets to see if that would resolve the pathological behavior. But in economics all we can do is adjust parameters — such as tax rates on wealthy elites, for example — and observe to see whether our theory (that said wealthy elites are accumulating massive amounts of cash that are being put to no productive use but, rather, are chasing speculative investments and otherwise are under a mattress from the viewpoint of the “real” economy) is correct that removing this cash from them via taxes (or tweaking taxes to force them to invest it in some productive enterprise rather than chase speculative investments) will resolve the problem of the economy being rather “bubbly” over the past 15 years or so. But is a specific model for how this would work accurate? We can look at historic data, and that’s suggestive, but economies are complex and what may have been applicable then may not be applicable now. (For example, the U.S. economy was rather hermetically sealed in the 1930’s — exports and imports were both fairly minimal parts of the economy — so data from the 1930’s may not be appropriate for today’s multi-national economies where, e.g., components in the computers my employer sells are made in Taiwan, China, South Korea, Malaysia, Thailand, and the United States).

I suppose what I am saying is that models are valuable, but they need to be tested against current conditions, and testing against historical conditions is by no means definitive. Otherwise we’d all be Austrians, since Austrian models clearly describe the conditions of late-19th-century railroad bubble economies (which we don’t live in today, thus why their models fail today).

oh, i should like to say again

that the very rich use their money not for consumption, but for power… and that has no natural diminishing marginal utility for them.

Ah Coberly. It appears that you are converging upon the central problem of anarchy theory, i.e., the problem of power. From an anarchy theory point of view, the problem with money is that money buys a lot of guns (expressed as “laws” in these civilized times, but laws are, in the end, backed up by guns, as those income tax protesters whose homes and cars are seized at gunpoint can testify), and of course as Mao observed, power grows from the barrel of a gun. More than a certain amount of money has diminishing marginal utility, but it doesn’t matter because as you correctly point out the problem is not one of marginal utility, it is one of power, and being more powerful than others is a real drive amongst certain primates.

Anarchy theory has no solution to the problem of power other than “eliminate anything which gives any person power over another person”, which is simply silliness (a 250 pound martial artist will always have more physical power over a 130 pound computer geek, duh), but of course in a democracy we have this notion that if We The People come together, we can use our combined power (a.k.a. GOVERNMENT) to counter those who would accumulate excess power at our expense.

None of which is strictly economics, other than that in our current universe, economics is as often an expression of power dynamics as it is a mechanism for allocating resources, and thus failing to account for the problem of power results in models which are, let us say, not applicable to this universe (though perhaps applicable to a universe where pink unicorns and cotton candy trees exist).

BT fair enough.

But your invocation of “modern economy” implicitly contrasts it with a preceding state of affairs whether that be Austrian Railroad barons, ‘traditionalists’, or ‘unicorn forest tenders’. This is particularly so when you identify specific components of that ‘modern economy’ and particularly wage suppression and asset concentration as being a specific product of that economy in direct, if implied, contrast to other and largely previous set of affairs.

But if that same combination of wage suppression and asset concentration was in fact typical of pre-industrial and non-western economies than the explanatory power of your model falls apart. Because either you have nothing to test it against “imaginary” or it actual fails you empirical causal test “historical”.

As to anarchy theory from where I sit you have set up the same false opposition as consumer/producer in (implied) free markets vs anarchy. Instead there is a middle course that postulates Pragmaticism informed by Enlightenment theories of Equality. If both Free Market economies where ‘producers’ (by monopoly of force or not) always end up with a disportionate share of wealth and Anarchy where all power flows from the barrel of a gun are shown to be equitable failures, there is an argument for a process of working towards equity on pragmatic ‘greatest good for greatest number’ democratic principles. Now while this may disappoint Purist Randites or Austrians on one side and Revolution Now Moaists on the other the overriding lesson of the New Deal and Great Society is “fuck them, we will do the best we can using the tools at hand, even if it is not as theoretically efficient as slave labor camps”

Perhaps you missed the part where I pointed out that anarchists correctly point out a central problem that informs our entire system of social organization (including our economic systems), i.e., the problem of power, but do not have any practical pragmatic solutions to said problem, rather focusing upon theoretical solutions that simply conflict with reality in this universe. I believe that has an implied call to pragmatism in its formulation.

Given that power dynamics are inherent in the human biology, it is no surprise that at other points in our history power dynamics have led to an accumulation of excess wealth (from a standpoint of marginal utility, i.e., more wealth than can be usefully consumed or invested) by small sets of people. By stating that this is a problem in our current economy, this by no means precludes the possibility, nay, the probability, that this has been a problem in past economies. I merely point out that certain structures in the current economy — such as corporatism — inherently give certain classes of people more redistributive power than others. I make no claims that there were no structures in past economies which similarly gave certain classes of people more redistributive power than others.

Note that I view Marxism, anarchy theory, etc., through the prism of “people who identify problems in the system of societal organization of their time but who have no practical solutions.” Again, an implied call to pragmatism vs. ideology.

This comment has been removed by the author.

“Actually, they spend less than their income each year (by construction, in this model), so their wealth increases each year.”

But Steve,

If you take your spreadsheet and change only the percentage consumed, the result is consuming more increases their wealth. It is true for the rich person as well, so there is actually no mechanism by which he would have a reduced propensity to spend.

Arne

I think your objection depends on people actually knowing the effects of which they are the cause.

i suspect (not at all knowledgeable myself) that there are results in game theory that explain all of this much better than “economics.”

Everyone trying to maximize his own short term (are there any other?) satisfactions results in less for him as well as everyone else in the long run.

On the other hand “excessive” cooperation may also result in something like a stagnation that fails to discover new and interesting ways to increase production for all.

In my life excessive competition has seemed more destructive than any attempt at cooperation. The only cooperation that seems to work is that enforced by an authority that has the means to compel or reward such cooperation.

I find myself more in agreement with Bad Tux… power is the problem, and there is no known solution, though “checks and balances” gave it a brave try.

Coberly,

It appears that a very small minority wrote some very large checks, and bought up all the balances.

nanute

exactly. I don’t think the Framers anticipated… or could have done anything about it if they did.. the rise of such concentrations of wealth that could buy most of the congress and all of the news media.

My objection is not to the behavior Steve wants to model, it is to the fact that the other aspects of his model produce incoherent results.

BT perhaps you missed the part where I suggested your imposition of Anarchy vs Markets as a way to wave away power problems (by suggesting Anarchists don’t have an answer so why bother) simply and unfairly excludes the historical middle term of Pragmatic Democracy. And no I don’t think you can just subsume and so dismiss pragmatism via some “implied call”that only you here.

American Pragmatism is not some subset of Anarchy either in practice, timeline, or theoretical approach. All I see is some version of “Dismiss Liberal Democracy. Because Gramsci”.

If this is more than special pleading to rescue your flawed over polarized argument I have yet to see it. Perhaps you could slow it down for us poor social democrats who naively cling to greatest good outcomes via democracy. And I am only half faceticious here.

Eighty years ago this was considered intuitively obvious.

You can actually use a simpler model.

Just evenly distribute income the first year. Let spending decline with rising income. Each round everyone spends according to their income. The money spent simply becomes next year’s income. Just it split evenly. You’ll quickly see a shrinking economy approaching the 100% spending point where everyone spends everything they take in. Money saved is money not spent.

If you introduce some noise into the spending rates you’ll quickly find that you have winners and losers in a shrinking economy. If you change income so that it depends, even slightly, on accumulated savings, you’ll have a shrinking economy with a wealthy 1%.

If you want a stable or growing economy, you have to inject money into the system either arbitrarily creating it or by redistribution.

I remember reading one paper in which a group tried to optimize heating and cooling an office building by giving each room a budget and creating a market for HVAC. They couldn’t get it to work until they arbitrarily confiscated all savings over a certain amount. Then, thanks to confiscatory taxes, the free market magic worked.

Eighty years ago this was considered intuitively obvious.

You can actually use a simpler model.

Just evenly distribute income the first year. Let spending decline with rising income. Each round everyone spends according to their income. The money spent simply becomes next year’s income. Just it split evenly. You’ll quickly see a shrinking economy approaching the 100% spending point where everyone spends everything they take in. Money saved is money not spent.

If you introduce some noise into the spending rates you’ll quickly find that you have winners and losers in a shrinking economy. If you change income so that it depends, even slightly, on accumulated savings, you’ll have a shrinking economy with a wealthy 1%.

If you want a stable or growing economy, you have to inject money into the system either arbitrarily creating it or by redistribution.

I remember reading one paper in which a group tried to optimize heating and cooling an office building by giving each room a budget and creating a market for HVAC. They couldn’t get it to work until they arbitrarily confiscated all savings over a certain amount. Then, thanks to confiscatory taxes, the free market magic worked.

@Arne: “…consuming more increases their wealth. It is true for the rich person as well, so there is actually no mechanism by which he would have a reduced propensity to spend.”

Two things: error of composition, and bookkeeping vs incentives.

*Aggregate* income and (production) surplus increases with spending. I’ve set it up so that is distributed proportionally to spending.

But *individuals* don’t know for sure that their income will increase with spending. So spending all their wealth might mean nothing to spend next year.

The poorer people only spend as large a percentage as they do because the utility provided outweighs the utility of the “substitute good”: predictable future economic security.

The poorer people only spend as large a percentage as they do because the utility provided outweighs the utility of the “substitute good”: predictable future economic security.

Excellent observation. It’s all about present value of the money vs future value of the money. Same reason bank lending slams shut during recessions and thus deflationary pressures arise during recessions — banks decide that loans made during better times will have greater value (fewer defaults, better interest rates, etc.) than loans made during recessionary times, and thus the future value of the money in their vaults is greater than the present value. So the money stays in their vaults (or, rather, on account at the Federal Reserve in these days). Of course this is what characterized the inflation / deflation cycles of the gold standard era, it’s inherent in the notion of fractional reserve lending, which in turn is pretty much a requirement for a capitalist system where the capital goods to generate future income are paid for by that future income, thus allowing capitalism to respond more quickly to changes in consumer demand than other systems of economic organization.

But to return to your point, if people view the future value of money to themselves as being greater than the present value of money, they will save this money rather than consume it, to the extent that this is true. The mechanisms via which they save are another issue, and can be characterized as lending the money vs. shoving it under mattresses, and examining those mechanisms would be very interesting. But that would be a subject for another tome.

One of the characteristics of the Great Recession is that people quit borrowing and started saving / paying down debt (in an economy where credit limits can be exchanged for money this is the same basic thing). This is because people viewed the future utility value of the money, when they possibly got laid off or their hours or wages got cut, as being greater than the current utility value of the money. But this appears to be a psychological calculation that individuals make. We may be able to model it on the aggregate scale, but our models will need to account for other factors that complicate the situation, such as government safety nets, which affects people’s perceptions of the future value of their money vs. the current value. If we had a stronger unemployment compensation system, for example, one that replaced current actual income for a significant period of time rather than being a pittance, consumer spending would not crash so hard during recessions because people would not fear losing their job so much. Modeling such a universe would be interesting from a policy making point of view, but not applicable to predicting the behavior of the current economy, where the U.S. unemployment compensation system is laughably parsimonious.