Payment Reform is key to better health

by Merrill Goozner

GoozNews

Hospitals are pushing back on an experiment that would put providers on budgets. CMS should ignore their lobbyists and consultants playing games with numbers.

Changing the way hospitals and doctors get paid is central to reforming our dysfunctional health care system. Payment reform can achieve better health outcomes, improve the patient experience and help keep overall health care costs in check, the three goals of any reform worthy of the name.

I am a partisan in this debate. Nearly two years ago, I co-wrote a two-part series in Health Affairs (here’s Part 1 and Part 2) touting Maryland’s payment system, which features common prices for all payers and capped hospital budgets. The four-person team was led by Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel of the University of Pennsylvania, a frequent advisor to Democratic administrations on health care policy.

Under all-payer pricing, hospitals charge every payer — whether a private insurer, Medicare, Medicaid, the Veterans Administration, or people without insurance — the same price for the same service. In every other state, hospitals charge varying rates: The uninsured pay the highest prices; private insurers (or, to be more precise, the employers and individual customers who buy their policies) pay on average 2 1/2 times what Medicare pays; and Medicaid and the VA pay the least.

Since the late 1970s, Maryland has retained a state-appointed commission (The horror! Government regulation!) to set hospital rates. Individual hospitals come before the Health Services Cost Review Commission when they want a rate increase, just like any other public utility. The hospitals document their costs and the commission sets rates that enable the institution to pay its bills and earn a small profit (or pad the endowment-like rainy day funds of non-profit hospitals, which most are).

During the past decade, Maryland made two major revisions to its all-payer pricing model, largely because hospitals had avoided its rate-control virtues by increasing the volume of services they delivered. In 2014, the state set budget caps for its hospitals, which limited their revenue growth each year to a percentage set by the commission. And in 2018, the state, with the federal government’s blessing, took their model one step farther: It set limits on the total cost of care (not just for hospitals but all medical services) for its Medicare beneficiaries.

Under this latest permutation of Maryland’s program, hospitals that hold total Medicare costs in check share those savings with the physician practices, nursing homes and other providers that collaborate in holding those costs below a fixed budget. The program also increased investment in primary care practices, giving these relatively low-paid physicians the financial support needed to coordinate care for individuals with complex medical needs.

In conducting a review of the Maryland experience, I spent weeks pouring over reviews conducted by outside evaluators hired by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS’ beancounters wanted to know whether government’s paying for the actual cost of care (establishing the same prices for government and private payers), when coupled with global budgets, had actually succeeded in limiting the growth in overall spending for Medicare beneficiaries. (Because all-payer pricing ends cost-shifting between various payers, the government pays Maryland hospitals more for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries than it does in other states. The flip side is that the privately insured pay less.)

The reviewers answered in the affirmative. “Between January 2014 and June 2018, uniform ‘all-payer’ pricing within hospitals coupled with global hospital budgets lowered Medicare spending in Maryland by nearly $1 billion, or about 10% of total hospital spending in the state, the review concluded. They also found that commercial insurers paid rates per inpatient admission that were 11 percent to 15 percent lower than what these insurers paid comparable hospitals in other states. (More on using comparable hospitals to measure success or failure rather than per capita spending in a moment.) Those lower prices were offset by the higher prices Medicare and Medicaid paid.

Given those results, CMS, which under the Affordable Care Act was empowered to experiment with various payment reforms, called Maryland’s all-payer pricing/budget cap system its most successful alternative payment experiment.

Last October, CMS’ Innovation Center followed up by unveiling an experimental program that will allow up to eight other states to adopt variations of the Maryland model. Dubbed AHEAD (for All-Payer Health Equity Approaches and Development), the agency will announce its first planning grant winners in July, a spokeswoman for the agency told me this week.

Industry pushback

As I noted in my story last October after the new program was announced, CMS did not include the most radical aspect of Maryland’s regulatory regime — all-payer price setting. That would require an act of Congress since setting a single price for each service would require raising Medicare and Medicaid rates to offset the fall in commercial rates, something that even a Democratic Party-led House and Senate would find difficult to embrace given the power of the hospital and insurance lobbies in Washington.

That’s unfortunate. The savings from all-payer pricing would be enormous. It would sharply reduce bloated administrative costs since hospitals would no longer have to maintain a dozen or more price schedules. It would put an end to the kabuki drama of insurer-hospital price negotiations that routinely comes up with price increases higher than underlying inflation.

But all-payer pricing was the bridge too far for the CMS Innovation Center. It would require increasing government spending to gross up Medicare and Medicaid. It would require capturing employer savings through higher taxes on profits and wages (employers could avoid higher taxes by adding their health insurance savings to workers’ paychecks, which is where they rightfully belong).

The Biden administration’s attempt to promote a more moderate version of the Maryland model did not assuage the hospital industry. Chip Kahn, CEO of the Federation of American Hospitals, which represents for-profit hospitals, immediately attacked the new program. “Global budgets, the foundation of the model, are the wrong way to go and are more likely to cause issues with access to care and stifle innovation as they are to hold down costs and improve quality and equity,” he said. “The evidence on this type of experiment is less than compelling.”

Then, last month, an article attacking the program by industry consultant Jeffrey Goldsmith appeared on the website of the Healthcare Financial Management Association, which represents hospital finance officers. This week, Goldsmith, whose research was funded FAH, followed up with an article on his own website.

He relied on data posted on the Kaiser Family Foundation website that reports the average cost of care for individuals (per capita spending) in every state in the union going back to 1991. Goldsmith compared Maryland’s growth in per capita spending over the next 30 years to the national average and to five other states (neighboring Pennsylvania and Virginia, and Wisconsin, Minnesota and Oregon, which have a significant share of their populations under insurance industry-led managed care).

“Despite Maryland’s long history of regulatory oversight of hospital rates, healthcare costs in the state in 2020 were higher, not lower, than the national average, and they have grown at virtually the same rate as the overall national rate over the past 30 years,” he said.

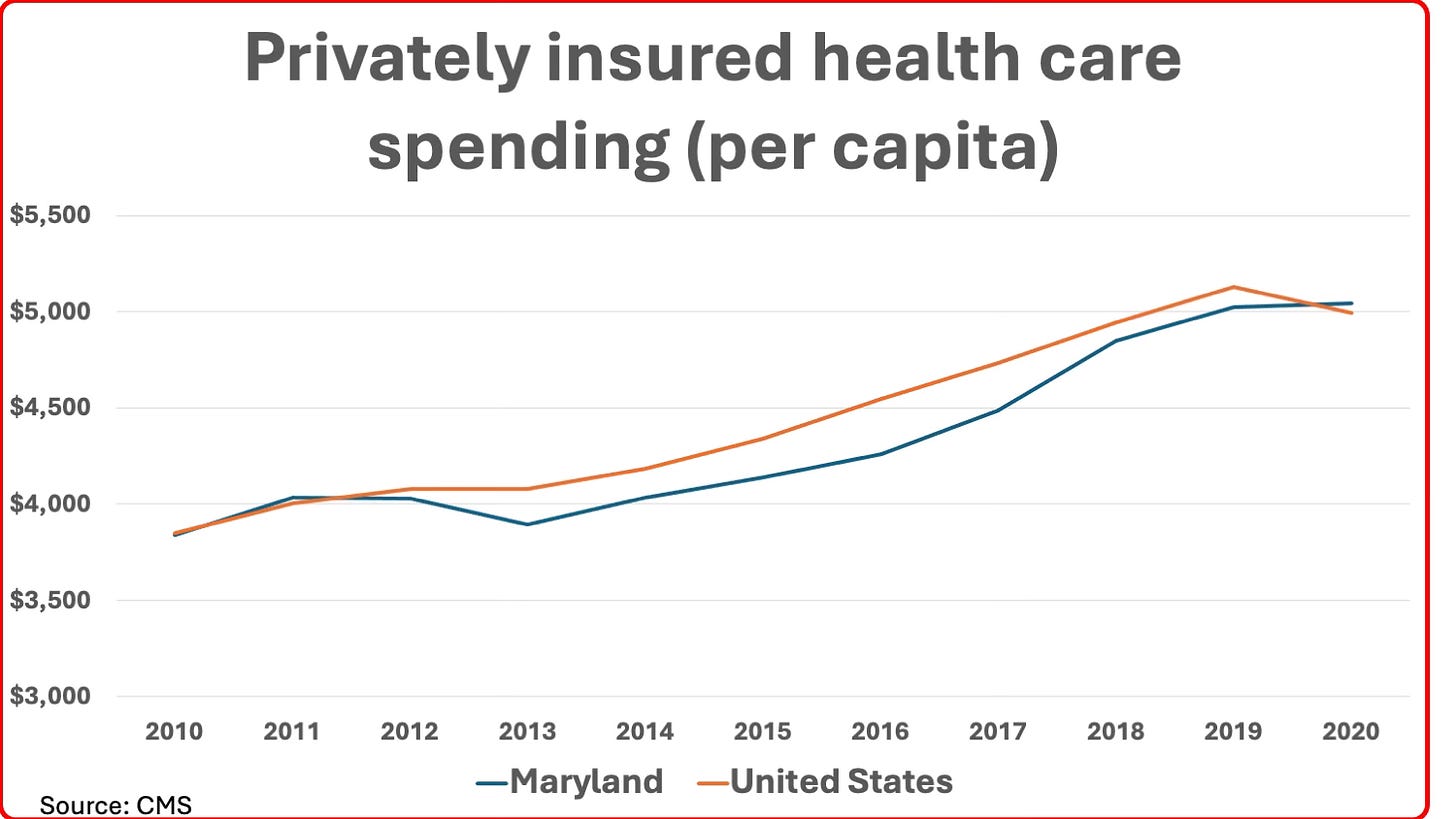

He also analyzed the growth in private health care spending by looking at per capita costs for people who are privately-insured, that is, not covered by Medicare, Medicaid or other government-funded programs. That KFF data on private spending only goes back to 2001. Again, he found that Maryland’s system, though “designed to minimize cost shifting to employers” has per capita private insurance health costs “higher than the national average and have grown at a faster rate than in the country as a whole.”

Fun with numbers

A lot can happen in 20 or 30 years, and a lot did happen to Maryland’s program since 1991. But to understand the evolution of the program, you have to go back to its beginnings in the 1970s to understand why Goldsmith’s numbers, while superficially accurate, are misleading.

Here’s the brief outline. The onset of rate regulation and all-payer pricing in 1974 had its intended effect almost immediately. Maryland’s per capita spending on health care went from 9th highest among all states and 2.4% above the national average in 1972 to 14th ranked and just 1% above the national average a decade later, according to older CMS data published in 1985.

But over the next three decades, two things happened that undermined rate regulation. First, the hospital industry embraced the deregulatory fervor of the Reagan era. Its leaders lobbied state legislators to end price oversight in the 27 states where it had been adopted. Maryland’s regulators, one of only two states to maintain the regime, hesitated denying their hospitals the same rate increases that were being “negotiated” between hospitals and insurers in neighboring states. Agency capture was alive and well in Annapolis.

The second and more important factor was the rise of private ambulatory surgical centers, often physician-owned. This moved a growing share of routine but lucrative surgeries like colonoscopies, cataract removal, and orthopedic tendon repair outside the four walls of the hospitals and thus not subject to rate regulation. Maryland saw more growth in ASCs than any other state in the nation.

By 2012, the year before the Affordable Care Act’s insurance expansion went into effect, per capita spending in Maryland had soared to 8.5% higher than the national average. However, the rise of ambulatory surgical centers and its impact on rising health care costs was happening in every high-income state. Maryland actually improved its state ranking on per capita costs, falling one place to 15th among all states.

Still, the federal government, alarmed by the rise in the extra payments for Maryland’s Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries needed to keep hospital rates level, threatened to end the experiment. That’s when Maryland turned first to capped budgets for its hospitals and, since 2018, to its total cost of care model, which involves providers outside the four walls of the hospital. By 2020, Maryland per capita spending ratio had fallen to 6.4% above the national rate and it lowered its ranking among all states to 16th.

And it would be a lot closer to the national per capita spending rate if 11 states, mostly from the old Confederacy, had expanded Medicaid and more aggressively pushed people to sign up for Obamacare plans on the federal or state exchanges. Having health insurance increases per capita spending on health care. The fact that some of the largest and wealthiest states in the nation (Texas, Georgia and Florida, in particular) also are among the states with the highest uninsured rates reduces per capita spending in those states and drags down the national average.

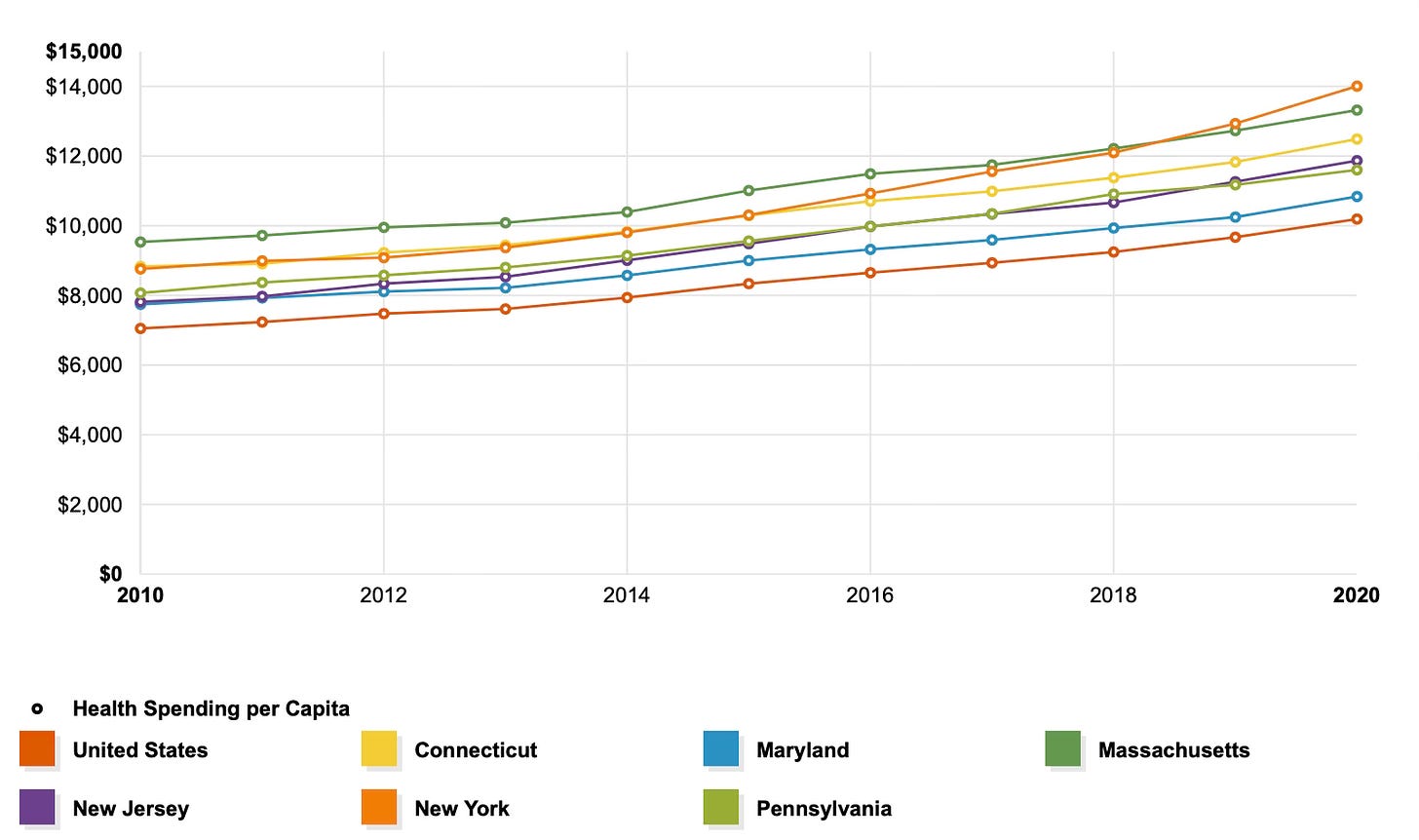

A good way to see the effect of Maryland’s experience in the last decade (when it coupled capped budgets for hospitals with all-payer price setting) is to compare the experience of Maryland and five other states — like Goldsmith — but not to its immediate neighbors or states with a heavy presence of managed care. Let’s look at states that are like Maryland in income and education; are geographically part of the same region; have a number of high-cost academic medical centers; and have one or more high poverty urban cores. I chose Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania (also in Goldsmith’s sample).

The following chart, produced by the KFF website, covers the first decade after the Affordable Care Act passed:

Every state in the Northeast and mid-Atlantic region began the decade with per capita health care costs above the national average (the red line at the bottom). Maryland (the blue line) in 2010 was about equal to New Jersey and Pennsylvania. But starting in 2012 and every year thereafter, Maryland’s costs rose at a slower rate than its regional peers. And if you look closely, Maryland global budgeting/total cost of care experiment actually narrowed the gap between the state’s per capita spending and the national average.

All payers must be involved

How about Goldsmith’s other major point: That Maryland’s private insurers (and their employer and individual customers) incurred higher costs per capita over the past two decades than either its neighboring states (Pennsylvania and Virginia) or the national average? A close look at the numbers shows this was, in fact, a very recent phenomenon and easily explainable.

If I had drawn the above chart using data from 2001 (the first year privately-insured per capita spending is available from CMS), it would have shown that at the dawn of the new millennium, Maryland’s per capita costs for the privately-insured was 5.6% below the national average. This starting point — not mentioned in Goldsmith’s article — is testimony to the initial power of all-payer pricing to reduce rates for the privately insured. As I noted earlier, Maryland had among the nation’s highest rates for the privately insured prior to the dawn of its regulatory system in the 1970s.

This held for most of the next decade, although the spread narrowed significantly during the steep recession of 2008-2010 and had almost disappeared by the time the ACA passed in 2010 because of the rise of ASCs. When Maryland adopted capped budgets for hospitals beginning in 2013, the rates for private insurance once again fell below the national average — a fact documented by CMS’ reviewers by comparing costs to comparable hospitals in other states. It was only in the last two years of the last decade that Maryland’s per capita costs for the privately insured began rising again and reached, in 2020, the slightly higher cost compared to the national average noted by Goldsmith.

Why did that happen? Simple. In 2018, Maryland and CMS agreed to its total cost of care model. But it only applied to Medicare’s fee-for-service beneficiaries — not the privately insured or Medicare Advantage patients, whose ranks were growing rapidly. Hospital systems and other providers no doubt concentrated on holding down the total cost of care for this narrower group through better care coordination and eliminating unnecessary hospitalizations. With FFS Medicare utilization in decline, the Maryland commission raised rates for all payers to ensure hospitals received their annual budgets.

Indeed, this adjustment accelerated during the pandemic, when discretionary use of hospital services collapsed and hospitals across the country — not just in Maryland — faced a financial catastrophe that required a massive bailout from the federal government. As I noted in a GoozNews article in February 2021 reporting on a research letter that appeared in JAMA, Maryland had the regulatory structure in place to raise rates for all its payers to help make up the shortfall.

Goldsmith concluded his article by claiming “the era of hyperinflation in health costs is over.” The real crises, he writes, “are affordability, declining life expectancy and huge gaps in care for the mentally ill and those requiring primary care.”

I have no quarrel with those priorities. Plus I support his prescription for limiting out-of-pocket expenses for all patients to a low percentage of total income no matter how high the bill. But he’s premature in declaring an end to the era of hospital and other providers’ price hikes and volume inflation.

The most recent economic indicators report from the non-profit Altarum showed the consumer price index for hospital and related services soared 7.9% in the past year. The CPI for health care overall (hospitals, physician offices, labs, nursing homes, etc.) was up just 2.8%, but when coupled with soaring volumes (up 4.3%) combined to send overall health care costs up 6.7% — higher than inflation plus economic growth.

Global budgeting that affects every aspect of health care delivery has the greatest potential to limit hospital utilization, which remains the single largest expense in health care.

It some ways, it would be like Medicare Advantage, where private insurers receive a fixed budget for all Medicare beneficiaries in their plans and then limit spending using tools like prior authorization, step therapy and outright denials of care. I’d rather give provider organizations the fixed budget and let their medical professionals make those decisions.

I conclude by noting the most salutary effect of fixed budgets. They would promote better health by giving provider organizations the power to allocate resources. They could spend more on prevention, primary care, behavioral health and the social services that can keep people out of the hospital.

But in order for that to succeed, the global budget/total cost of care model must cover every payer, not just Medicare beneficiaries as in Maryland. CMS made a wise choice when it insisted in its call for AHEAD applications that at least one insurer be included in every proposal.

Do they calculate per capita costs for the whole population or only those who have health care? It’s easy to keep costs down if you can keep people from getting insurance.

Kaleberg:

Early on in the article: “Under all-payer pricing, hospitals charge every payer — whether a private insurer, Medicare, Medicaid, the Veterans Administration, or people without insurance — the same price for the same service. In every other state, hospitals charge varying rates: The uninsured pay the highest prices; private insurers (or, to be more precise, the employers and individual customers who buy their policies) pay on average 2 1/2 times what Medicare pays; and Medicaid and the VA pay the least.”

I think that answers your question of inclusiveness.

Bill

maybe not. what i think Kaleberg may have been getting at is that if all or most people did not have insurance prices would come down. Maybe not, but there is certainly incentive for wordless collusion between providers and insurers to keep prices up.