The Rising Burden of Government Debt

By Daniel Bergstresser

Second of two commentaries on Government Debt. This commentary does mention tax policies since 2000 which reduced revenue. The latest passed in 2017 as advocated by trump and supported by Congress. It passed under Reconciliation. The failure to balance out the debt created by the tax reduction with revenue achieved through economic growth will force a repeal of it.

Here, the author discusses the dreag on the economy and citizens due to increasing debt not covered by revenue.

The Issue:

Interest payments on federal government debt are projected to reach $892 billion in 2024.

This is more than the government is projected to spend on defense. It is almost a third higher than what the United States spent on debt interest payments in 2023.

The increase reflects the combination of the rise in US government debt and higher interest rates. Interest rates are expected to inch lower in the coming years as inflation subsides. However the counter to this as the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) forecasts, interest payments as a percent of GDP will continue to rise. The extent of this increase was not foreseen even in the recent past years. The CBO’s projections of the interest burden of the debt have been steadily increasing.

Briefly, The Facts:

The current high cost of servicing the national debt is partly a reflection of the historically large size of the federal government debt.

Government debt is the sum of current and accumulated past budget deficits as well as the cumulative cost of financing those deficits. There has been a notable increase in US government debt since the economic downturn of the Great Recession. Government debt required increased federal spending which lowered tax revenues. It was followed by the pandemic shock. In addition, there has been a lasting downshift in government revenues due to changes in tax policy since 2000, which has also significantly contributed to the mismatch between government revenues and government spending. Debt-to-GDP levels have been higher than at any time since the late 1940s. At $28.2 trillion, the total federal debt held by the public is projected to be 99% of GDP by the end of 2024.

The cost of servicing the debt has also been rising as a result of increasing interest rates.

Interest rates have been high as the Federal Reserve raised its benchmark Fed funds rate from near zero in March of 2022 to a range of 5.25-5.5% in July of 2023. This increase was to fight the inflation surge following the pandemic recovery. As a result, borrowing costs have risen. The yield on the 10-year Treasury bill was 4.2% in June 2024, as yields have hit the highest levels in 15 years. While the Federal Reserve is expected to begin reducing the Fed funds rate as the slowdown in inflation continues, the Congressional Budget Office forecasts that the rate on 10-year Treasury notes will decline slowly to 3.6% by the fourth quarter of 2026 and then rise gradually again, reaching 4.1% by 2034.

The combination of large debt and high interest rates means that the federal government’s cost of servicing its debt relative to national income is reaching all-time highs.

At a projected $892 billion in 2024, interest payments on the federal debt represent 3.1% of GDP in 2024. Since 1940, net outlays for interest have never exceeded 3.2 percent of GDP. In the CBO’s June 18, 2024 outlook, government spending on debt service is forecast to exceed that percentage every year from 2025 to 2034. About two-thirds of the growth in net interest costs forecast from 2024 to 2034 stems from expected increases in the average interest rate on federal debt, and the remaining third reflects the expected increase in the amount of debt.

The interest burden of the debt partially depends upon the maturity structure of the debt.

The US Treasury considers tradeoffs when deciding how to finance the current budget deficit and the rolling over of maturing debt. One decision involves the pattern of maturities of outstanding debt. The US Treasury issues debt with maturities as short as one month and as long as 30 years. Short-maturity debt requires frequent rolling-over of the debt which makes the Treasury susceptible to greater volatility in interest payments. Longer maturity debt such as 30-year Treasury bonds typically pay higher interest rates than shorter maturity debt such as 3-month Treasury bills (although not always, and not recently).

Most of the outstanding debt in late 2022 was scheduled to mature within the subsequent three years. That debt has been refinanced at higher interest rates, sharply raising debt service costs. For example, ~ $7 trillion worth of debt held by the public was refinanced during the 2023 fiscal year (October 2022 through September 2023). Each percentage point increase in interest rates on that refinanced debt meant $70 billion per year more in net interest payments in that first year (for context, this is about 10 percent of the entire United States defense budget). The maturity structure of debt remains very short, with half of outstanding debt now maturing by 2026. Recent forecasts of interest on the debt reflect the fact that large amounts of federal debt will be rolled over at higher rates.

Servicing the federal debt has been taking up an increasingly larger share of government spending.

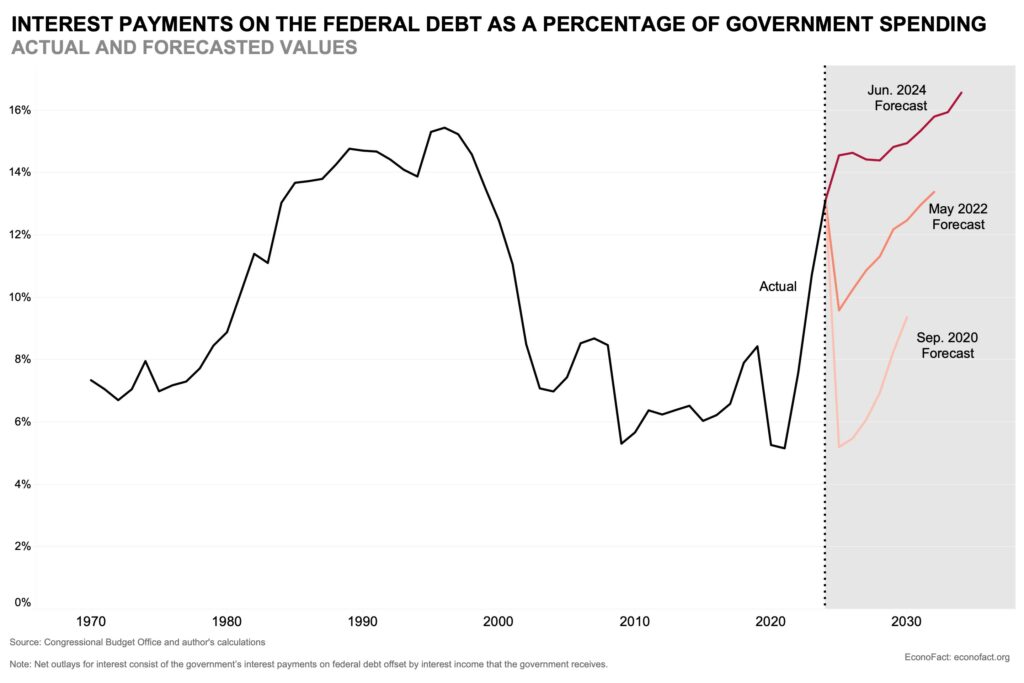

Interest payments made up about 13 percent of federal spending in 2024. It being the third highest category of spending ahead of spending on defense, Medicare, and income security programs (see here). This is a sharp increase from 2017, when net interest payments made up closer to 7% of government outlays. The increase is approaching the situation experienced in the mid-1990s when net interest payments reached over 15 percent of fiscal outlays (see chart). This was at a time when the overall debt held by the public as a percentage of GDP grew from 23 percent to 48 percent. The reduction of debt payments from the mid-1990s to the mid-2010s reflects both lower interest rates and a lower level of debt. Although the debt-to-GDP ratio rose between 2009 and 2017, net interest payments as a share of total federal outlays remained below 7 percent during this period primarily because of low interest rates.

Projections of the interest burden of the debt have increased dramatically over the past four years.

The Congressional Budget Office currently projects that interest payments on debt will be more than 16 percent of federal spending in 2034. Current projections are well above those made two or four years ago (see chart). The differences between forecast and actual values, and the rising forecasts over time, reflect the effects of changing expectations on both interest rates and debt.

What this Means:

Higher interest payments mean less government spending is available for defense, social safety net programs, research, and other important government functions. Rising levels of debt service contribute to fiscal challenges that our country faces. As interest payments become a higher share of government outlays, the US may cut spending on other categories or raise tax revenues in order to keep deficits from ballooning and require even more borrowing.

The cost of debt service will depend on both the level of debt outstanding and the level of interest rates. Debt has risen to levels that are high by historical standards. Until recently the increase has coincided with very low interest rates that have kept the costs of debt service relatively low. However, the high levels of debt mean increases in interest rates like those that we have seen over the past two years will have a large impact on our country’s budget deficits. Which the deficits could require increases in taxes or reductions in spending.

Cut the so called defense budget!

More than half the US’ “discretionary” expenditures are for war!

Several times the rate of war spending as the rest of OEDC!

War is more the cause of debt than actions by the ‘ways and means’ committee.

The US debt/GDP ratio currently stands at 123% according to the IMF. Japan’s debt/GDP ratio is 263%. AFAIK, Japan isn’t experiencing hyperinflation.

Constraints on government spending based on debt represent a manufactured problem. Raise the debt ceiling and it goes away.

Joel:

I would contend there is no need to increase debt if the program passed will pay for itself in economic growth for the US and not solely for a minority of taxpayers. This I believe you already know as well as others who read here. The author does discuss this briefly:

“there has been a lasting downshift in government revenues due to changes in tax policy since 2000, which has also significantly contributed to the mismatch between government revenues and government spending. “

He speaks of the trump 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of which a large portion was skewed to the upper 10% of taxpayers. If thee were to reverse the 2017 tax break for the upper 20% of taxpayers, it would pay for the lower 80%.

There is also issue with the 2001 and 2003 tax breaks.

@Bill,

In other words, there’s no need to increase debt if we remove the reasons to increase debt. Agreed.

You and I both know that there aren’t the votes to do meaningful things like cut the defense budget and reverse the Reagan, Bush and Trump tax cuts. Since we can’t do the things that would *actually* reduce the deficits and the debt, we’re left with GOP hostage-taking and the lies that SS and Medicare have to be cut.

I understand well how we got there. And I understand well why we cannot reverse that pathway. My only point is that I feel under no obligation to hyperventilate over the USA’s national debt or to cave to Republican pressure to cut social programs to “solve” the problem they created.

Joel:

I understand your point and agree.

We have an opportunity in 2025 to allow the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act to end itself as it was passed using Reconciliation as the means of passing it. I believe Biden and Dems will make the effort to revise it and restore taxes to some of our constituency. Biden will have nothing to lose if re-elected. And he has been proposing many programs which he did not do as a Senator. One issue in particular, he has been a major opponent of as a Senator is Student Loans relief.

So yes I am with you on your point. I would promte fixing the issue if we can do so.

D’accord.

Duncan Black over at Eschaton states the problem well:

Most of us don’t get to be there, but there are always people with access to lawmakers and the administration who are constantly putting pressure on them. The people trying to make noise on the outside – furious blog posts, angry tweets, public protest – are the ones who don’t ever get that access.

Some of that pressure comes from big donors, some from their weirdo rich friends in the group chat, some from the numerous lobbying groups who have armies of people who are paid to lie for their cause (and who also have all your favorite journalists in their contact lists). And, of course, those who dangle lifetime friends and family jobs.

It’s the “quiet” pressure people should be more worried about. It is constant and relentless and more more effective than anything outsiders can do.

Joel:

I do not believe we have done furious posting at Angry Bear. I understand how the sausage is made and my former Econ Prof agrees with my stance and the basis for it. Much of my work was spent in studying the economy and applying it to domestic global manufacturing. It is nice to see manufacturing “planning” to return to the US.

I am planning a road trip to the Midwest to visit him while I am still capable and capable of driving. I also have need to sit and talk with another mentor who worked with me when we consulted at various manufacturing facilities such as Caterpillar, etc.

I am catching grief over driving there on a road trip. Nothing like seeing the countryside around you which is impossible in an airplane. A final walkabout.

The moneyed people which are a part of the 1% or less of the population are the ones to fear. They can afford to gamble where the other 80% or so percent of us can not. I have no political influence other than to say “I told you so” and then to move on.

Angry Bear is very fortunate to have people like Robert Waldman and yourself for that matter who can speak to the technical aspects of certain topics. I strive to recruit others.

Hey, got anything to post today? 🙂

Great conversation.

The “furious blog posts” comment was Duncan Black, not me. I doubt he was referring specifically to Angry Bear.

I’m still casting around for a post, but haven’t yet come up with something that meets AB standards.

JoeL

Whatever your commentary, it meets Angry Bear’s supposed standards. I have not been disappointed yet.

I am very glad to see that Angry Bears are not overswayed by the debt hysteria promoted by Bergstresser.

There is a very simple answer to the debt problem..if it is a problem: raise taxes to pay for what we buy buy/need to keep the country prosperous and safe. “But we don’t have the votes.” and I should add, we don’t have the people who will vote for higher taxes.

Neither people nor corporations worry too much about “debt.” It is a normal part of business, and a normal part of ordinary life (home mortgages. I am not sure credit card debt is “normal” or healthy, but there it is.

Bergstressers comoparisons are silly: “service on the debt costs more than spending on defense.: that’s like saying my home mortgage costs more than my gun collection. He also sneaks in a reference to “income security programs.” I assume he is talking about Social Security which pays for itself and has nothing to do with “the debt.”

I don’t know if he intends to mislead. But it looks like he read a few summaries somewhere and rolled in all the numbers and top of the head analysis into a meaningless salad of words that contribute to debt hysteria but do nothing to address the issues or even understand them.

We can pay for what we need. That would certainly lower the debt/deficity. but that is not what “we” want. We want to cut spending on “incomme security programs” and Medicare, so we can ejoy our tax cuts and consolidate our power with our billion dollar incomes.

The debt is bigger than at any time since the late forties.”” Well, we got through it then. We can get though it now. If only we can find the votes.

again, sorry about the typos, sorry if they cause real trouble.

Dale:

I do not agree with Associate Prof. Bergstresser; but, know the background before calling them out. His credential allows him you make the comments he did. We should be answering with similar rebuttal that is supported. For one thing, raising taxes is political and difficult to achieve with most people. Every Senator and Representative having a minimal majority at home may be reluctant to jump right in. One Representative found such out the hard way. Jamal Bowman found such out with his attacks on Israel.

In both commentaries I have posted from Econofact, I have found them to be lacking in areas which you point out. If Biden allows the trump tax break to revert back to what taxes were, do you believe many people will be happy with that occurring? I think not; but it must be taken to task in 2025 and much of it must be changed as it benefits a few (corporations and the top 19% in income). That is an argument we can make and the numbers are available.

While Biden will be in his last 4 years, he still needs the support of an overall Democrat Congress. He can not and should not endanger his Senate and House support.